The Life of Moses Austin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1963 Fred Geary's "The Steamboat Idlewild' Published Quarterly By The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Sacretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1963 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1964 WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK C BARNHILL, Marshall W. C HEWITT, Shelbyville FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. -

Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids Recommended Citation DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio, "Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992" (2020). Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection. 160. https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids/160 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 Descriptive Summary Creator: Stumpf, Ella Ketcham Daggett (1903-1993) Title: Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866-1914-1992 Dates: 1866, 1914-1992 Creator Ella Ketcham Daggett was an active historic preservationist and writer Abstract: of various subjects, mainly Texas history and culture. Content Consisting primarily of short manuscripts and the source material Abstract: gathered in their production, the Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers include information on a range of topics associated with Texas history and culture. Identification: Col 6744 Extent: 16 document and photograph boxes, 1 artifacts box, 2 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder Language: Materials are in English Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note A fifth-generation Texan, Ella Ketcham Daggett was born on October 11, 1903 at her grandmother’s home in Palestine, Texas to Fred D. -

LOTS of LAND PD Books PD Commons

PD Commons From the collection of the n ^z m PrelingerTi I a JjibraryJj San Francisco, California 2006 PD Books PD Commons LOTS OF LAND PD Books PD Commons Lotg or ^ 4 I / . FROM MATERIAL COMPILED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE OF TEXAS BASCOM GILES WRITTEN BY CURTIS BISHOP DECORATIONS BY WARREN HUNTER The Steck Company Austin Copyright 1949 by THE STECK COMPANY, AUSTIN, TEXAS All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper. PRINTED AND BOUND IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PD Books PD Commons Contents \ I THE EXPLORER 1 II THE EMPRESARIO 23 Ml THE SETTLER 111 IV THE FOREIGNER 151 V THE COWBOY 201 VI THE SPECULATOR 245 . VII THE OILMAN 277 . BASCOM GILES PD Books PD Commons Pref<ace I'VE THOUGHT about this book a long time. The subject is one naturally very dear to me, for I have spent all of my adult life in the study of land history, in the interpretation of land laws, and in the direction of the state's land business. It has been a happy and interesting existence. Seldom a day has passed in these thirty years in which I have not experienced a new thrill as the files of the General Land Office revealed still another appealing incident out of the history of the Texas Public Domain. -

Changes in Spanish Texas

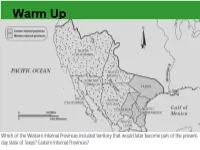

Warm Up The Mexican National Era Unit 5 Vocab •Immigrant - a person who comes to a country where they were not born in order to settle there •Petition - a formal message requesting something that is submitted to an authority •Tejano - a person of Mexican descent living in Texas •Militia - civilians trained as soldiers but not part of the regular army •Empresario -the Spanish word for a land agent whose job it was to bring in new settlers to an area •Anglo-American - people whose ancestors moved from one of many European countries to the United States and who now share a common culture and language •Recruit - to persuade someone to join a group •Filibuster - an adventurer who engages in private rebellious activity in a foreign country •Compromise - an agreement in which both sides give something up •Republic - a political system in which the supreme power lies in a body of citizens who can elect people to represent them •Neutral - Not belonging to one side or the other •Cede - to surrender by treaty or agreement •Land Title - legal document proving land ownership •Emigrate - leave one's country of residence for a new one Warm Up Warm-up • Why do you think that the Spanish colonists wanted to break away from Spain? 5 Unrest and Revolution Mexican Independence & Impact on Texas • Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla – Gave a speech called “Grito de Dolores” in 1810. Became known as the Father of the Mexican independence movement. • Leads rebellion but is killed in 1811. • Mexico does not win independence until 1821. Hidalgo’s Supporters Rebel Against Spain • A group of rebels led by Juan Bautista de las Casas overthrew the Spanish government in San Antonio. -

December 1969

• The phrase, "From the River to Rome," defines the geographical range apparent in the contents of this issue of the magazine. Initial focus is on St. Charles as the home of The Lindenwood Colleges, the historic city which celebrated this year the 2QOth anni versary of its founding. A photograph on the inside back cover, showing a January-term class studying art and my thology in Rome, dramatizes Lindenwood's reach from St. Charles to the campus of the world. Yet in addition to the geographical, the magazine empha sizes another dimension of Lindenwood: that of time. The front cover, combining a modernistic outdoor light at the New Fine Arts Building with a page from the 1828 diary of Lindenwood's co founder, George C. Sibley, symbolizes the historic past complement ing the dynamic present. How Lindenwood has built on tradition to spearhead programs in private education in the Sixties is evident from pages 2 through 48. Certain articles illmninating the old and the new, the near and the far should be of special interest. "The Possible Dream," beginning on page 7, is the most recent investigation of Lindenwood's history; "The Ghosts of Lin denwood" sheds light on some of the renowned dead in the campus cemetery. Companion stories, which almost shatter the generation gap, reveal the Now Generation's reaction to a 72-year-old student in the dormitory, while the lady in question proves that a senior citizen, like any other minority, can .Bnd happiness on this open campus. Then there is a photo essay capturing the exuberance that attended the opening of the New Fine Arts building. -

Lieutenant Governor of Missouri

CHAPTER 2 EXECUTIVE BRANCH “The passage of the 19th amendment was a critical moment in our nation’s history not only because it gave women the right to vote, but also because it served as acknowledgement of the many significant contributions women have made to our society, and will make in the future. As the voice of the people of my legislative district, I know I stand upon the shoulders of the efforts of great women such as Susan B. Anthony and the many others who worked so diligently to advance the suffrage movement.” Representative Sara Walsh (R-50) OFFICE OF GOVERNOR 35 Michael L. Parson Governor Appointed June 1, 2018 Term expires January 2021 MICHAEL L. PARSON (Republican) was sworn in The governor’s proposal to improve economic as Missouri’s 57th governor on June 1, 2018, by and workforce development through a reorgani- Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary R. Russell. zation of state government was overwhelmingly He came into the role of governor with a long- supported by the General Assembly. Through time commitment to serving others with over 30 these reorganization efforts, government will be years of experience in public service. more efficient and accountable to the people. Governor Parson previously served as the The restructuring also included several measures 47th lieutenant governor of Missouri. He was to address the state’s growing workforce chal- elected lieutenant governor after claiming victory lenges. in 110 of Missouri’s 114 counties and receiving Governor Parson spearheaded a bold plan to the most votes of any lieutenant governor in Mis- address Missouri’s serious infrastructure needs, souri history. -

Missouri Historical Revi Ew

MISSOURI HISTORICAL REVI EW. CONTENTS Howard High School, The Outstanding Pioneer Coeducational High School in Missouri Dorothy B. Dorsey Cadet Chouteau, An Identification John Francis McDermott Plank Roads in Missouri North Todd Gentry The Career of James Proctor Knott in Missouri Edwin W. Mills Missouriana Historical Notes and Comments Missouri History Not Found in Textbooks 5TATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of MISSOURI VOL. XXXI APRIL, 1937 No. S OFFICERS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI, 1935-1938 •GEORGE A. MAHAN, Hannibal, President. ALLEN McREYNOLDS, Carthage, First Vice-President. WALTER B. STEVENS, St. Louis, Second Vice-President. C. H. McCLURE, Kirksville, Third Vice-President. MARION C. EARLY, St. Louis, Fourth Vice-President. B. M. LITTLE, Lexington, Fifth Vice-President. JOHN T. BARKER, Kansas City, Sixth Vice-President. R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer. FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Secretary and Librarian. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1937 C. P. DORSEY, Cameron. WM. R. PAINTER, Carrollton. EUGENE FAIR, Kirksville. W. J. SEWALL, Carthage. THEODORE GARY, Kansas City. H. S. STURGIS, Neosho. HENRY J. HASKELL, Kansas City. JONAS VILES, Columbia. L. M. WHITE, Mexico. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1938 T. H. B. DUNNEGAN, Bolivar. *JOHN ROTHENSTEINER, BEN L. EMMONS, St. Charles. St. Louis. STEPHEN B. HUNTER, E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville. Cape Girardeau. CHAS. H. WHITAKER, Clinton. ISIDOR LOEB, St. Louis. ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville. Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1939 WILSON BELL, Potosi. JUSTUS R. MOLL, Springfield. CHARLES B. DAVIS, St. Louis. ELMER N. POWELL, FORREST C. DONNELL, St. Louis. Kansas City. ELMER O. JONES, LaPIata. WM. SOUTHERN, Jr., HENRY KRUG, Jr^, St. -

The Story of the Holland House

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 9 | Issue 2 Article 5 10-1971 Home of Heroes: The tS ory of the Holland House Cecil E. Burney Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Burney, Cecil E. (1971) "Home of Heroes: The tS ory of the Holland House," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol9/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL JOURNAL 109 HOME OF HEROES The Story of the Holland House CECIL E. BURNEY About three and one-half miles out of Anderson on the Anderson-Navasota Highway is what is believed to be one of the oldest Anglo houses in Texas-the Francis Holland House. Dating from the earliest days of Stephen F. Austin's Old Three Hundred, the house has been the scene of more tragedy than triumph. Stra tegically located on the early immigrant trails, the dwelling was a place of hospi • tality for early colonists as they headed toward the La Bahia cros..'ling of the Brazos River and down to San Felipe de Austin. It was a gathering place for colonists as they came to cast their votes for officers in the Austin Colony. During the spring of 1834, as dreaded cholera crept up the Brazos, disease almost wiped out all of the residents of the house. -

Hollinger Box Finding Aid | Mary E. Ambler Archives | Lindenwood Library

Hollinger Box Finding Aid 0001-999 The Sibleys and Lindenwood Buildings, History, Miscellaneous 1000-1999 Lindenwood Presidents, Board of Directors, Publications 2000-2999 Lindenwood Faculty 3000-3999 Lindenwood Students (Activities, papers, organizations) 4000-4999 Lindenwood Alumni 6000-6999 Lindenwood Sports 9000-9999 Non-Lindenwood Items Oversize, Clam and DVD boxes have an assortment of all of the above. B0001 George and Mary Sibley Series F1 Mary Sibley- Correspondence, Last Will & Testament (1816-1894) F2 Mary Sibley- Diary- Photocopy (1832-1858) F3 Mary Sibley- Diary- Transcript (1832-1858) F4 Mary Sibley- House of Bethany Transcripts (1866-1869) F5 Mary Sibley- Miscellaneous F6 Mary Sibley- Images F7 George and Mary Sibley- Articles F8 George and Mary Sibley- Miscellaneous Transcripts (1806-1857) Mary Sibley: Remember These Things, Kathryn McCann Coker B0002 George and Mary Sibley Series F1 George Sibley- Images F2 George C. Sibley- Diary (1808-1811)- Transcripts, 1826 (photocopy) F3 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1820-1828) F4 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1833-1843) F5 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1843-1844) F6 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1845-1846) F7 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1847-1848) F8 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1851-1856) F9 George C. Sibley- Commonplace Papers –Transcripts (1856) F10 George C. Sibley- Miscellaneous B0003 George and Mary Sibley Series F1 George C. Sibley- Factory System (1802-1822) F2 George C. Sibley- Mexican Road Commission (1825) F3 George C. Sibley- Mexican Road Commission (1826) F4 George C. Sibley- Mexican Road Commission (1827) F5 George C. Sibley- Mexican Road Commission (1828-1831) F6 George C. -

St. Louis Streets Index (1994)

1 ST. LOUIS STREETS INDEX (1994) by Dr. Glen Holt and Tom Pearson St. Louis Public Library St. Louis Streets Index [email protected] 2 Notes: This publication was created using source materials gathered and organized by noted local historian and author Norbury L. Wayman. Their use here was authorized by Mr. Wayman and his widow, Amy Penn Wayman. This publication includes city streets in existence at the time of its creation (1994). Entries in this index include street name; street’s general orientation; a brief history; and the city neighborhood(s) through which it runs. ABERDEEN PLACE (E-W). Named for the city of Aberdeen in north-eastern Scotland when it appeared in the Hillcrest Subdivision of 1912. (Kingsbury) ABNER PLACE (N-S). Honored Abner McKinley, the brother of President William McKinley, when it was laid out in the 1904 McKinley Park subdivision. (Arlington) ACADEMY AVENUE (N-S). The nearby Christian Brothers Academy on Easton Avenue west of Kingshighway was the source of this name, which first appeared in the Mount Cabanne subdivision of 1886. It was known as Cote Brilliante Avenue until 1883. (Arlington) (Cabanne) ACCOMAC BOULEVARD and STREET (E-W). Derived from an Indian word meaning "across the water" and appearing in the 1855 Third City Subdivision of the St. Louis Commons. (Compton Hill) ACME AVENUE (N-S). Draws its name from the word "acme", the highest point of attainment. Originated in the 1907 Acme Heights subdivision. (Walnut Park) ADELAIDE AVENUE (E-W & N-S). In the 1875 Benjamin O'Fallon's subdivision of the O'Fallon Estate, it was named in honor of a female relative of the O'Fallon family. -

Powerpoint Presentation

The Texas Revolution Do we have expectations of modern day immigrants? What are those expectations? Spanish Texas The Spanish had been in the Americas since Columbus in 1492. Spain owned a large part of North America, including Texas. The Spanish Settle Texas The mission system The mission system ends The Spanish attempted to settle Native Americans rejected Texas by building missions, small mission life, where they were settlements designed to convert expected to give up their culture the Indians to Christianity. as well as their religion. The Spanish had effectively used Some Indian groups viewed the the mission system in Mexico. Spanish as dangerous trespassers, attacking the They built two dozen missions missions and towns. and presidios between the late 1600s and 1700s; they also built The system was built to convert San Antonio and Nacogdoches. the Indians and to thwart French claims. In 1762, France ceded to Despite Spanish hopes, the Spain much of its land claim in missions failed and the towns North America. never flourished. By 1800, Spain still claimed Texas, but had only three settlements in the region. Tejanos In 1821, only about 4,000 Tejanos lived in Texas. Tejanos are people of Spanish heritage who consider Texas their home. The Spanish government tried to attract Spanish setters to Texas, but very few came. Moses Austin An American, Moses Austin was given permission by the Spanish government to start a colony in Texas. All the Americans had to do was follow Spanish laws. Moses died in 1821, so his son Stephen tried to start the colony.