The Ming Shi-Lu As a Source for Southeast Asian History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: the Emergence of the Yunnanese

Between Winds and Clouds Bin Yang Chapter 5 Sinicization and Indigenization: The Emergence of the Yunnanese Introduction As the state began sending soldiers and their families, predominantly Han Chinese, to Yunnan, 1 the Ming military presence there became part of a project of colonization. Soldiers were joined by land-hungry farmers, exiled officials, and profit-driven merchants so that, by the end of the Ming period, the Han Chinese had become the largest ethnic population in Yunnan. Dramatically changing local demography, and consequently economic and cultural patterns, this massive and diverse influx laid the foundations for the social makeup of contemporary Yunnan. The interaction of the large numbers of Han immigrants with the indigenous peoples created a 2 new hybrid society, some members of which began to identify themselves as Yunnanese (yunnanren) for the first time. Previously, there had been no such concept of unity, since the indigenous peoples differentiated themselves by ethnicity or clan and tribal affiliations. This chapter will explore the process that led to this new identity and its reciprocal impact on the concept of Chineseness. Using primary sources, I will first introduce the indigenous peoples and their social customs 3 during the Yuan and early Ming period before the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Second, I will review the migration waves during the Ming Dynasty and examine interactions between Han Chinese and the indigenous population. The giant and far-reaching impact of Han migrations on local society, or the process of sinicization, that has drawn a lot of scholarly attention, will be further examined here; the influence of the indigenous culture on Chinese migrants—a process that has won little attention—will also be scrutinized. -

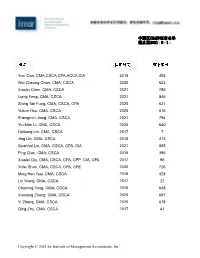

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

The Sinicization of Indo-Iranian Astrology in Medieval China

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 282 September, 2018 The Sinicization of Indo-Iranian Astrology in Medieval China by Jeffrey Kotyk Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out for peer review, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Download 375.48 KB

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TAR:PRC 31175 TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE (Financed by the Cooperation Fund in Support of the Formulation and Implementation of National Poverty Reduction Strategies) TO THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR PARTICIPATORY POVERTY REDUCTION PLANNING FOR SMALL MINORITIES August 2003 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 July 2003) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) Y1.00 = $0.1208 $1.00 = Y8.2773 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank FCPMC – Foreign Capital Project Management Center LGOP – State Council Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation and Development NGO – nongovernment organization PRC – People's Republic of China RETA – regional technical assistance SEAC – State Ethnic Affairs Commission TA – technical assistance UNDP – United Nations Development Programme NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 31 December (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This report was prepared by D. S. Sobel, senior country programs specialist, PRC Resident Mission. I. INTRODUCTION 1. During the 2002 Asian Development Bank (ADB) Country Programming Mission to the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Government reconfirmed its request for technical assistance (TA) for Participatory Poverty Reduction Planning for Small Minorities as a follow-up to TA 3610- PRC: Preparing a Methodology for Development Planning in Poverty Blocks under the New Poverty Strategy. After successful preparation of the methodology and its adoption by the State Council Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation and Development (LGOP) to identify poor villages within the “key working counties” (which are eligible for national poverty reduction funds), the Government would like to apply the methodology to the PRC's poorest minority areas to prepare poverty reduction plans with villager, local government, and nongovernment organization (NGO) participation. -

Download Download

StudyontheInteractionoftheSinicizationofChristianityand theReconstructionofCrossGborderEthnicMinoritiesƳCulturesinYunnan〔1〕 ZhiyingGAOandDongleiWANG (YunnanUniversityandYunnanUniversityofFinanceandEconomics,Kunming,YunnanProvince,P.R.China) Abstract :TheSinicizationofChristianity,whichisthedevelopingstrategyandpracticeto makeChristianityadaptto Chineseculture.ItcorrespondstotheChristianizationofChineseethnic minoritypeoplewhobelievedinChristianity. Fromtheperspectiveofculturalinteraction,borrowingandblending,thestudyexploresthe motivation,processand characteristicsoftheinteractivedevelopmentbetweenthelocalizationandcontextualizationofChristianityin Yunnan ethnicminorities ‘areasandtheChristianizationofethnic minorities’culturesbyhistoricalcombingandsynchronic comparison.Mostly between Christianity and ethnic minoritiesƳ traditional cultures had experienced from the estrangement,andcoexistedwitheachotherandblendingprocess,andfinishedtheChristianfrom “in”tothetransitionof “again”,soastorealizetheSinicizationalcharacteristicsoftheregional,national,butalsomaketheborderethniccultural reconstruct. KeyWords :Yunnanethnicminorities;Sinicization;Christianization;Interactivedevelopment Author :GaoZhiying,Professor,PhD,CenterforStudiesofChineseSouthwestƳsBorderlandEthnicMinoritiesofYunnan University.Tel:13888072229Email:2296054891@qq.com WangDonglei,ViceProfessor,PhD,SchoolofInternational LanguagesandCulturesofYunnanUniversityofFinanceandEconomics.Tel:15887015580Email:1609766878@qq.com Ⅰ.TheOriginoftheTopic JustasZhuoXinpingsaid,ItisnecessaryforforeignreligionssuchasBuddhism,Christianity -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

A Selective Study on Chinese Art Songs After 1950

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 A Selective Study on Chinese Art Songs after 1950 Gehui Zhu [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Zhu, Gehui, "A Selective Study on Chinese Art Songs after 1950" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8287. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8287 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Selective Study on Chinese Art Songs after 1950 Gehui Zhu A Doctoral Research Project Submitted to College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice Performance Hope Koehler, D.M.A, Committee Chair and Research Adviser William Koehler, D.M.A Matthew Heap, Ph.D. Victor Chow, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2021 Keywords: Chinese Art Songs after 1950, Contemporary Chinese Art Songs, Chinese Poems, Chinese Art Songs for Classical Singers. -

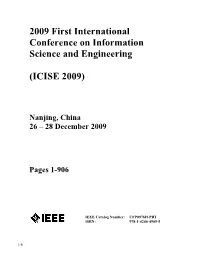

A Dynamic Schedule Based on Integrated Time Performance Prediction

2009 First International Conference on Information Science and Engineering (ICISE 2009) Nanjing, China 26 – 28 December 2009 Pages 1-906 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP0976H-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-4909-5 1/6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TRACK 01: HIGH-PERFORMANCE AND PARALLEL COMPUTING A DYNAMIC SCHEDULE BASED ON INTEGRATED TIME PERFORMANCE PREDICTION ......................................................1 Wei Zhou, Jing He, Shaolin Liu, Xien Wang A FORMAL METHOD OF VOLUNTEER COMPUTING .........................................................................................................................5 Yu Wang, Zhijian Wang, Fanfan Zhou A GRID ENVIRONMENT BASED SATELLITE IMAGES PROCESSING.............................................................................................9 X. Zhang, S. Chen, J. Fan, X. Wei A LANGUAGE OF NEUTRAL MODELING COMMAND FOR SYNCHRONIZED COLLABORATIVE DESIGN AMONG HETEROGENEOUS CAD SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................12 Wanfeng Dou, Xiaodong Song, Xiaoyong Zhang A LOW-ENERGY SET-ASSOCIATIVE I-CACHE DESIGN WITH LAST ACCESSED WAY BASED REPLACEMENT AND PREDICTING ACCESS POLICY.......................................................................................................................16 Zhengxing Li, Quansheng Yang A MEASUREMENT MODEL OF REUSABILITY FOR EVALUATING COMPONENT...................................................................20 Shuoben Bi, Xueshi Dong, Shengjun Xue A M-RSVP RESOURCE SCHEDULING MECHANISM IN PPVOD -

Ming China As a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2018 Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 Weicong Duan Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Duan, Weicong, "Ming China As A Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, And Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620" (2018). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1719. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/1719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Dissertation Examination Committee: Steven B. Miles, Chair Christine Johnson Peter Kastor Zhao Ma Hayrettin Yücesoy Ming China as a Gunpowder Empire: Military Technology, Politics, and Fiscal Administration, 1350-1620 by Weicong Duan A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 St. Louis, Missouri © 2018, -

MEDIEVAL WORLD from the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade W@

The History of the M E D I E V A L WORLD % Also by Susan Wise Bauer The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome (W. W. Norton, 2007) The Well-Educated Mind: A Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had (W. W. Norton, 2003) The Story of the World: History for the Classical Child (Peace Hill Press) Volume I: Ancient Times (rev. ed., 2006) Volume II: The Middle Ages (rev. ed. 2007) Volume III: Early Modern Times (2004) Volume IV: The Modern Age (2005) The Complete Writer:Writing with Ease (Peace Hill Press, 2008) The Art of the Public Grovel: Sexual Sina and Public Confession in America (Princeton University Press, 2008) With Jessie Wise The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home (rev. ed., W. W. Norton, 2009) The History of the MEDIEVAL WORLD From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade W@ S u s a n W i s e B a u e r B W . W . Norton New York London Copyright © 2010 by Susan Wise Bauer All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110. Maps designed by Susan Wise Bauer and Sarah Park and created by Sarah Park Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, pages 000–000 constitute an extension of the copyright page. Manufacturing by Book Design by Margaret M. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of OPIUM REDUCTION in BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES from the WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone a Thesis Submitted in Part

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION Mr. Sai Lone A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Program in International Development Studies Faculty of Political Science Chulalongkorn University Academic Year 2008 Copyright of Chulalongkorn University เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับทองถิ่นในเขตวา นายไซ โลน วิทยานิพนธน ี้เปนสวนหนึ่งของการศึกษาตามหลกสั ูตรปริญญาศิลปศาสตรมหาบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาการพัฒนาระหวางประเทศ คณะรัฐศาสตร จุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย ปการศึกษา 2551 ลิขสิทธิ์ของจุฬาลงกรณมหาวิทยาลัย Thesis title: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION By: Mr. Sai Lone Field of Study: International Development Studies Thesis Principal advisor: Niti Pawakapan, Ph. D. Accepted by the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master’s Degree ___________________________ Dean of the Faculty of Political Science (Professor Charas Suwanmala, Ph.D.) THESIS COMMITTEE ___________________________ Chairperson (Professor Supang Chantavanich, Ph.D.) ___________________________ Thesis Principal Advisor (Niti Pawakapan, Ph.D.) ___________________________ External Examiner (Decha Tangseefa, Ph.D.) นายไซ โลน: เศรษฐศาสตรการเมืองของการปราบฝนในประเทศพมา: มุมมองระดับ ทองถิ่นในเขตวา (THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF OPIUM REDUCTION IN BURMA: LOCAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE WA REGION) อ. ทปรี่ ึกษา: ดร.นิติ ภวัครพันธุ. 133 หนา. งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้เนนศึกษาผลกระทบดานเศรษฐกิจสังคมของโครงการพัฒนาชนบทที่ดําเนินงานโดยองคกร -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries.