Student Resource Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

8Th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map

8th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map Music Reading: Student will be able to read and perform one octave major and melodic minor scales in the keys of EbM/cm; BbM/gm; FM/dm; CM/am; GM/em; DM/bm; AM/f#m Student will be able to read and perform key changes. Student will be able to read and correctly perform accidentals and understand their duration. Student will be able to read and perform simple tenor clef selections in cello/bass; treble clef in viola Violin Students will be able to read and perform music written on upper ledger lines. Rhythm: Students will review basic time signature concepts Students will read, write and perform compound dotted rhythms, 32nd notes Students will learn and perform basic concepts of asymmetrical meter Students will review/reinforce elements of successful time signature changes Students will be able to perform with internal subdivision Students will be able to count and perform passages successfully with correct rhythms, using professional counting system. Students will be able to synchronize performance of rhythmic motives within the section. Students will be able to synchronize performance of the sections’ rhythm to the other sections of the orchestra. Pitch: Student is proficient in turning his/her own instrument with the fine tuners. Student is able to hear bottom open string of octave ring when top note is played. Students will review and reinforce tuning to perfect 5ths using the following methods: o tuning across the orchestra o listening and tuning to the 5ths on personal instrument. Student performs with good intonation within the section. -

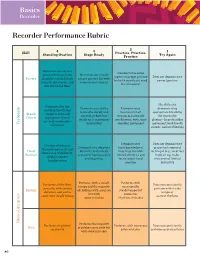

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Cistercian Preparatory School: the First 50 Year

CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS 1962 2012 David E. Stewart Headmasters CISTercIAN PreparaTORY SCHOOL 1962 - 2012 Fr. Damian Szödényi, 1962 - 1969 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1969 - 1974 Fr. Henry Marton 1974 - 1975 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1975 - 1981 Fr. Bernard Marton, 1981 - 1996 Fr. Peter Verhalen ’73, 1996 - 2012 Fr. Paul McCormick, 2012 - Fr. Damian Szödényi Fr. Henry Marton Headmaster, 1962 - 1969 Headmaster, 1974 - 1975 (b. 1912, d. 1998) (b. 1925, d. 2006) Pictured on the cover (l-r): Fr. Bernard Marton, Abbot Peter Verhalen ’73, Fr. Paul McCormick, and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy. Cover photo by Jim Reisch CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS David E. Stewart ’74 Thanks and acknowledgements The heart of this book comes from over ten years of stories published in The Continuum, the alumni magazine for Cistercian Prep School. Thanks to Abbot Peter Verhalen and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy and many other monks, faculty members, staff, alumni, and parents for their trust and willingness to share so much in the pages of the magazine and this book. Christine Medaille contributed her time and talent to writing Chapter 8 and Brian Melton ’71 contributed mightily to Chapter 11. Thanks to Jim Reisch for his outstanding photography throughout this book, and especially for the cover shot. Priceless moments from the sixties were captured by or provided by Jane Bret and Fr. Melchior Chladek. Thanks to Rodney Walter for collecting the yearbook photographs used in the book and identifying the students in them. Thanks to Fr. Bernard Marton, Sylvia Najera, and Bridgette Gimenez for their help in editing and proofing. -

59Th Annual Critics Poll

Paul Maria Abbey Lincoln Rudresh Ambrose Schneider Chambers Akinmusire Hall of Fame Poll Winners Paul Motian Craig Taborn Mahanthappa 66 Album Picks £3.50 £3.50 .K. U 59th Annual Critics Poll Critics Annual 59th The Critics’ Pick Critics’ The Artist, Jazz for Album Jazz and Piano UGUST 2011 MORAN Jason DOWNBEAT.COM A DOWNBEAT 59TH ANNUAL CRITICS POLL // ABBEY LINCOLN // PAUL CHAMBERS // JASON MORAN // AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE AU G U S T 2011 AUGUST 2011 VOLUme 78 – NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

The Advance Project

Formal Evaluation of the ADVANCED DRIVER AND AD VEHICLE ADVISORY NAVIGATION CONCEPT DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government, but neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, the Argonne National Laboratory, the ADVANCE Parties, or the member institutions of the Illinois Universities Transportation Research Consortium make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process discussed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. The ADVANCE Targeted Deployment: The Evaluation Manager’s Overview Report, Sections 1 through 10 of Volume 1 of this document, and the Executive Summary have been authored by a contractor of the U.S. Government under contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38. Accordingly, the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. THE ADVANCE PROJECT: FORMAL EVALUATION OF THE TARGETED DEPLOYMENT VOLUME 3 by Evaluation Manager Argonne National Laboratory Evaluation Teams Castle Rock Corporation, Inc. -

Musical Piano Performance by the ACT Hand

2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation Shanghai International Conference Center May 9-13, 2011, Shanghai, China Musical Piano Performance by the ACT Hand Ada Zhang1;2, Mark Malhotra3, Yoky Matsuoka3 Department of Bioengineering1, Department of Music2, Department of Computer Science and Engineering3 University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Abstract— In the past, the music community conducted research on what makes music more musical or expressive. Much of this work has focused on the manipulation of phras- ing, articulation and rubato to make music more expressive. However, it has been difficult to study neuromuscular control used by experts to create such musical music. This paper took a first step toward this effort by using the Anatomically Correct Testbed (ACT) Robotic Hand to mimic the way expert humans play when they are instructed to perform “musically” or “robotically.” Results from 22 human subjects showed that musical expression contained a larger range of dynamics and different articulation than robotic expression, while there was no difference in the use of rubato. The ACT Hand was controlled to the level of precision that allowed the replication of expert expressive performance. Its performance was then rated by 17 human listeners against music played by a human expert to show that the ACT Hand could play as musically as an expert human. Furthermore, articulation, phrasing, and Fig. 1. The Anatomically Correct Testbed Hand rubato were tested in isolation to determine the importance of articulation over phrasing and rubato. This type of study will lead to understanding how to implement future robots to and legs to depress the pedals. -

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality by Martha Edwards In this article, I’m going to talk about a simple thing that you can do to make you, your band mates, and your dance community fall in love with the music that you make. It’s called phrasing. Yup, phrasing. Musical phrasing is a lot like verbal phrasing. Sentences start somewhere and end somewhere, just like music. Sometimes they start soft, and grow and grow until they END! SOMETIMES they start big and taper off at the end. Sometimes they grow and get BIG and then taper off at the end. But a lot of people never notice that music does the same thing, that it comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. When you help it do that, you’re really sending a musical experience to your audience. Otherwise, you’re just typing. What do I mean by typing? I mean that, if all you do is play the notes, one after another, at the same intensity from beginning to end, you could play the notes perfectly, but your playing would be boring. You wouldn’t be shaping the phrase, you would just be sending out a kind of telegraph message with no emotion attached. I think it happens because playing music is hard, and it’s a big challenge just to be able to play the notes of a tune at all. When you finally get the notes of a tune, one after another, it’s a kind of victory. But don’t stop with just the notes. Learn to play musically! photo of Miranda Arana, Jonathan Jensen and Martha Edwards (courtesy Childgrove Country Dancers, St. -

Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry Through a Laban Based Pedagogy a Laban Based Pedagogy

Workshop In Teaching Musicianship and Artistry Through Movement and Kinesthetic Workshop In TeachingA Mwaurseincieasns sohfi pH aonwd S Aourntids tMryo Tvehsr Fouogrhw aMrdo vement and Kinesthetic Awareness of How So und Moves Forward Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through A Laban Based Pedagogy A Laban Based Pedagogy James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Choral Consultant-We-music.com Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Co-Director-The Choral Institute at Oxford (rider.edu/oxford) ChoralGiamusic.com/Jordan Consultant-We-music.com Co-Director-The ChoralTwitter@Jevoke Institute at Ox ford (rider.edu/oxford) Giamusic.com/Jordan Twitter@Jevoke The Principles of Artistry Through the Door of Kinesthetic Learning This space-memory-combined with our continuous process of anticipation, is the source of our sensing time as time, and ourselves as ourselves (p.164) Carlo Rovelli In The Order of Time Few people will realize that a page of musical notes is to a great extent a description or prescription of bodilly motivations or of the way how to move your muscles, limbs and breathing organs…in order to produce certain effects (p.39). Rudolf Laban In Karen K. Bradley Rudolf Laban Musicians who do not audiate shifting weight perform with displaced energy (p.190) Edwin Gordon In Learning Sequences in Music (2012) The rhythm texture of music…In its total effect on the listener, the rhythm of music derives from two main sources, melodic and harmonic (p.123) It is assumed that the conceptions meter and rhythm are understood.