Improving Race Equality in Crime and Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Economic Statistics, January 2021 SB 3/2021

28 January 2021 Key Economic Statistics, January 2021 SB 3/2021 Key points for September 2020 to November 2020 About this bulletin The latest Labour Force Survey data (September to November 2020) continues to show impacts on the labour market as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) This monthly bulletin pandemic. used to be a The employment rate in Wales was 72.4%, down 0.2 percentage points on compendium previous quarter and 2.4 percentage points from a year earlier. This is the publication that second largest annual decrease since the series began in 1992 brought together the The unemployment rate in Wales was 4.6%, up 0.8 percentage points from latest key statistics the previous quarter and up 1.6 percentage points over the year, below the relating to the Welsh UK rate of 5.0%. This is the largest annual increase in the unemployment economy and labour rate since July to September 2011. market. There were 16,000 redundancies in Wales. This is the highest redundancy Since June 2020, this level in Wales since records began in 2009. has been changed to Employment rate (percentage of population age 16-64) focus mainly on the 78 Labour Market and 76 more specifically focus 74 UK on the impacts of 72 Wales COVID19 on the 70 labour market 68 66 Key supporting 64 material: Welsh Economy in 2001 2004 2007 2008 2011 2014 2017 2018 1999 2000 2002 2003 2005 2006 2009 2010 2012 2013 2015 2016 2019 2020 Numbers Source: Labour Force Survey, Office for National Statistics Other data sources In this bulletin The latest official labour market estimates cover the period September to November This bulletin contains 2020. -

HORIZON 2020 in WALES Annual Report 2018

HORIZON 2020 IN WALES Annual Report 2018 Cronfeydd yr UE: Buddsoddi yng Nghymru EU Funds: UNDEB EWROPEAIDD Investing in Wales EUROPEAN UNION FOREWORD We are delighted to introduce this fourth annual Horizon 2020 report in what has been a landmark year for Wales with our businesses and universities passing the €100m milestone in funding secured through this highly competitive and world-leading programme. Through our participation in Horizon 2020, Wales is now playing its part in global projects worth €1.4 billion and involving almost 3,000 international collaborative links across 70 nations. Since the 2017 annual report, funding secured by Welsh organisations has increased by 24%, taking the current figure to nearly €103m. This strong performance demonstrates the strength and resilience of Welsh research and innovation during a period where UK engagement in Horizon 2020 has been impacted by the uncertainties of Brexit. Kirsty Williams AM Minister for Education As our policy paper ‘Protecting research and innovation after EU Exit’1 makes clear, over the past 20 years, the volume, quality, impact and international reach of Welsh research has consistently grown. We are now one of the most efficient research performers in converting relatively small levels of funding into highly regarded research, in many cases outperforming other UK nations and similar sized countries from around the world. Horizon 2020 is a unique programme due to the scale of its support for multilateral international collaboration and is an important element of the Welsh research and innovation landscape. The programme enables the best research teams from around the world to come together on multi-disciplinary projects. -

Preparations for Replacing EU Funding for Wales

National Assembly for Wales Finance Committee Preparations for replacing EU funding for Wales September 2018 www.assembly.wales The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/SeneddFinance Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Finance Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddFinance © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2018 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Finance Committee Preparations for replacing EU funding for Wales September 2018 www.assembly.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 22 June 2016 to carry out the functions of the responsible committee set out in Standing Orders 18.10, 18.11, 19 and 20 of the National Assembly for Wales. Under Standing Orders 19 and 20, the committee’s responsibilities include considering any report or document laid before the Assembly concerning the use of resources, or expenditure from the Welsh Consolidated Fund. This includes undertaking budget scrutiny of the bodies directly funded from the Welsh Consolidated Fund. -

HORIZON 2020 in WALES Annual Report 2016

HORIZON 2020 IN WALES Annual Report 2016 Cronfeydd yr UE: Buddsoddi yng Nghymru EU Funds: UNDEB EWROPEAIDD Investing in Wales EUROPEAN UNION Foreword I am very pleased to introduce the second annual report of Horizon 2020 activity in Wales. Last year was eventful in many ways but as our jointly launched White Paper ‘Securing Wales’ Future: Transition from the European Union to a new relationship with Europe’ (https://beta.gov.wales/ brexit) makes very clear Horizon 2020 is an important EU programme for Wales. It creates economic benefits and valued partnerships and collaborations – particularly among our universities and businesses, so it is vital we continue to participate fully in Horizon 2020 and its successor programme after the UK leaves the EU. Horizon 2020 is open for business and, as this report demonstrates, organisations across Wales are benefitting significantly from the opportunities it presents. Last October I was pleased to announce that we had achieved a significant milestone, with Welsh organisations benefiting from over €54m of Horizon 2020 funds. The importance and relevance of this investment can be seen in the many success stories covered in this report; for example, Nantgarw based SME Biocatalysts Ltd is using €0.3m of Horizon 2020 funding to advance further its position as a leading manufacturer of enzymes to support food, fragrance, diagnostics and pharmaceutical industries, while €0.7m of Horizon 2020 funds for Bangor University’s INMARE project is helping to develop industrial applications, including pharmaceuticals, from marine proteins. The strong performance since the last annual report, which sees the number of participations from Welsh organisations almost doubling and over €19m awarded to Wales in just 11 months, is a considerable achievement that we can build on together in the months and years ahead. -

Key Economic Statistics: November 2020 , File Type

12 November 2020 Key Economic Statistics, November 2020 SB 37/2020 Key points for July 2020 to September 2020 About this bulletin The latest Labour Force Survey data (July to September) shows some of the largest impacts on the labour market seen during the pandemic to date. This monthly bulletin Unemployment and employment both had the largest quarterly changes in used to be a Wales since records began in 1992 compendium publication that July to September 2020 saw the largest number of redundancies in Wales since mid-2009, with numbers significantly higher than in recent years brought together the latest key statistics The employment rate in Wales was 72.1%, down 2.5 percentage points on relating to the Welsh previous quarter and 1.8 percentage points from a year earlier. economy and labour The unemployment rate in Wales was 4.6%, up 1.9 percentage points from market. the previous quarter and up 0.8 percentage points over the year and below the UK rate of 4.8% Since June, this has Employment rate (percentage of population age 16-64) been changed to focus mainly on the Labour Market and more specifically focus on the impacts of COVID19 on the labour market Key supporting material: Welsh Economy in Numbers Other data sources In this bulletin The latest official labour market estimates cover the period July - September 2020. Other data sources, such as the number of paid employees presented later in this This bulletin contains headline, can also be used to produce a more complete picture. new data on: Experimental claimant count data showed 114,000 claimants in Wales in Employment 3 September 2020, a rate of 7.5% of the workforce. -

Wales Insights Report 2021

Section 1 What is it Like to be a Girl in Wales? THE STATE OF GIRLS’ RIGHTS IN THE UK 2019-2020 WALES2 The State of Girls’ Rights INSIGHTS in the U.K 2019-2020, Wales Insights Report REPORT Section 1 What is it Like to be a Girl in Wales? ABOUT PLAN INTERNATIONAL UK Plan International UK strives to deliver and protect the rights of millions of children – especially girls – across Latin America, Africa, Asia and the UK. We work to give every child the same chance in life. But when you’re a girl it is even harder to be safe, to be in school and to be in charge of your body. We know that girls’ rights are global; wherever in the world a girl is born or lives, she should be safe, free from abuse, and have equal rights. That is why, in 2016, we turned our attention to the UK; to play our role in ensuring girls’ rights are realised here as well. Through our research, advocacy and programmes, we advance transformative change to ensure that girls in the UK can learn, lead, decide and thrive in the process of realising their rights. Report design by Hannah Moore www.hannahmmoore.com Photography by Joyce Nicholls www.joycenicholls.com Cover photo: Poppy, 16, Newport This report - and our work across the UK - is supported by players of People’s Postcode Lottery. 1 The State of Girls’ Rights in the UK 2019-2020, Wales Insights Report CONTENTS Summary of Key Findings 5 Introduction 9 Section 1: what is it like to be a girl in Wales? 12 Learn 13 Educational Attainment 13 Gender and Subject Choice 14 Safety at School 15 Classroom Behaviour and Exclusions -

Official Statistics

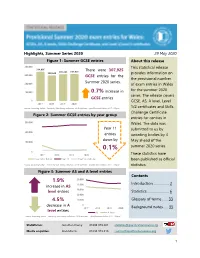

Highlights, Summer Series 2020 29 May 2020 Figure 1: Summer GCSE entries About this release 400,000 This statistical release 334,095 There were 307,925 305,745 307,925 290,640 provides information on 300,000 GCSE entries for the the provisional number Summer 2020 series. 200,000 of exam entries in Wales for the summer 2020 100,000 0.7% increase in series. The release covers GCSE entries 0 GCSE, AS, A level, Level 2017 2018 2019 2020 Source: Awarding bodies - Entries by Year Group collection, 2018 and later - Qualifications Wales; 2017 - Ofqual 1/2 certificates and Skills Challenge Certificate Figure 2: Summer GCSE entries by year group entries for centres in 300,000 Wales. The data was Year 11 submitted to us by 200,000 entries awarding bodies by 4 down by 100,000 May ahead of the summer 2020 series. 0.1% 0 These statistics have 2017 2018 2019 2020 Year 10 or below Year 11 Year 12 or above been published as official Source: Awarding bodies - Entries by Year Group collection, 2018 and later - Qualifications Wales; 2017 - Ofqual statistics. Figure 3: Summer AS and A level entries Contents 1.9% 50,000 Introduction…………….. 2 increase in AS 40,000 level entries 30,000 Statistics…….…............... 6 20,000 4.5% 10,000 Glossary of terms..….. 33 decrease in A 0 2017 2018 2019 2020 Background notes...... 35 level entries AS A level Source: Awarding bodies - Entries by Year Group collection, 2018 and later - Qualifications Wales; 2017 - Ofqual Statistician: Jonathan Davey 01633 373 261 [email protected] Media enquiries: Alan Morris 01633 373 216 [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION Qualifications Wales is the regulator of qualifications, other than degrees, and the qualifications system in Wales. -

HORIZON 2020 in WALES Annual Report 2015

HORIZON 2020 IN WALES Annual Report 2015 Cronfeydd yr UE: Buddsoddi yng Nghymru EU Funds: UNDEB EWROPEAIDD Investing in Wales EUROPEAN UNION 2 Foreword I am delighted to introduce our the significant progress made in first Annual Report of Horizon utilising these funds to help build 2020 activity in Wales. capacity among organisations to access funding from the Worth €77 billion Horizon 2020 competitive Horizon 2020 is the largest ever European programme. Excellent examples Union research and innovation of synergies between Structural programme, and to help drive Funds and Horizon 2020, as in world-class science and innovation the case of Sêr Cymru II, are and sustainable jobs and growth rightly attracting interest from in Wales, it is vital that we Europe, and we are sharing our maximise the opportunities that experiences and best practice with this programme presents. our EU partners. It is already clear that Horizon Wales needs to build on this 2020 is more competitive than momentum and this report its predecessor Framework highlights areas where we can Programme 7 (FP7), but despite work together to improve on this Welsh organisations have our performance so far. The EU already succeeded in attracting Funding Ambassadors, whom I over €35m of investment from appointed in December 2014, Horizon 2020. Furthermore, have highlighted the importance with the UK being one of the of Welsh organisations building largest recipients of Horizon 2020 on their networks in Brussels and funding in the EU, Wales has beyond. The European Territorial increased its share of the funding Co-operation programmes, invested in UK organisations including the Ireland Wales from 2.07% to 2.46% when programme, also present compared to the predecessor FP7 opportunities for us to utilise the programme. -

Early Policy Response to COVID-19 in Education—A Comparative Case Study of the UK Countries

Early policy response to COVID-19 in education—A comparative case study of the UK countries Melissa Mouthaan, Martin Johnson, Jackie Greatorex, Tori Coleman, Sinéad Fitzsimons1 Research Division Introduction In this article, we report on a series of analyses that we carried out during the early course of the pandemic. In early 2020, researchers in the Education and Curriculum Team in Cambridge Assessment Research Division started a project that we called Curriculum Watch. The aim of this project was to collate a literature and documents database of education and curriculum policies, research and analyses from across the four countries of the United Kingdom (UK). Our work was inspired by the work of Raffe et al. (1999) who set out the positive benefits gained from comparing the policies of “the UK home nations”2. We anticipated that our Curriculum Watch database would provide a growing resource that could inform our understanding of education and curriculum issues beyond the UK. The literature base would also serve as an archive of events and our reflections on them. This is particularly useful as the presence of policy documents is sometimes short-lived, reflecting movements in policy decision-making. As the pandemic hit the UK in February 2020, it affected education policy in ways that were difficult to foresee. It was also challenging at the time to make sense of the policy shifts that were occurring. This context presented us with an opportunity to use our literature base to make sense of the emerging educational picture. Having a base of comparative policy and research literature allowed us to see how policy developments converged or diverged across the different countries of the UK, allowing us insight into some of the issues influencing education decision-making. -

Key Economic Statistics, December 2020 SB 42/2020

17 December 2020 Key Economic Statistics, December 2020 SB 42/2020 Key points for August 2020 to October 2020 About this bulletin The latest Labour Force Survey data (August to October 2020) shows some of the largest impacts on the labour market seen during the pandemic. This monthly bulletin used to be a The employment rate in Wales was 72.4%, down 1.4 percentage points on previous quarter and 1.9 percentage points from a year earlier. compendium publication that The unemployment rate in Wales was 4.6%, up 1.4 percentage points from brought together the the previous quarter and up 1.0 percentage points over the year and below the UK rate of 4.9%. latest key statistics relating to the Welsh There were 13,000 redundancies in Wales. This is the second highest economy and labour redundancy level since November to January 2013. Redundancy figures for July to September 2020 were the highest seen in over a decade. market. Since June, this has Employment rate (percentage of population age 16-64) been changed to focus mainly on the Labour 78 Market and more 76 specifically focus on 74 UK the impacts of 72 Wales COVID19 on the 70 labour market 68 66 Key supporting 64 material: Welsh Economy in 1999 2002 2005 2008 2011 2013 2016 2019 2000 2001 2003 2004 2006 2007 2009 2010 2012 2014 2015 2017 2018 2020 Numbers Source: Labour Force Survey, Office for National Statistics Other data sources In this bulletin The latest official labour market estimates cover the period August to October This bulletin contains 2020. -

The COVID-19 Long Term Care Situation in Wales

Long term care and the COVID-19 crisis in Wales Siôn Jones and Pietro Patrignani Last updated 11 June 2020 Authors Siôn Jones (LE Wales and London Economics) and Pietro Patrignani (LE Wales and London Economics). ltccovid.org This document is available through the website ltccovid.org, which was set up in March 2020 as a rapidly shared collection of resources for community and institution-based long-term care responses to COVID-19. The website is hosted by CPEC at the London School of Economics and Political Science and draws on the resources of the International Long Term Care Policy Network. Corrections and comments are welcome at [email protected]. This document was last updated on 11 June 2020 and may be subject to revision. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access document distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported International License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Suggested citation Jones S and Patrignani, P (2020) Long term care and the COVID-19 crisis in Wales. LTCcovid, International Long- Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE, 11 June 2020. Follow us on Twitter @LE_Wales @LondonEconomics Acknowledgments With thanks to our colleagues Shaan Devnani and Rhys Williams for constructive comments. ltccovid.org | Long term care and COVID-19 in Wales 1 1. Key points • The first COVID-19 case in Wales was confirmed on 28 February 2020 and the first COVID-19 death in Wales was recorded on 16 March. -

Change? Travel Tracker Wave 4 Report February-March 2021 Ben Marshall, Lore Bizgan, Glenn Gottfried

All change? Travel tracker Wave 4 report February-March 2021 Ben Marshall, Lore Bizgan, Glenn Gottfried © Ipsos | Doc Name | Month Year | Version # | Public | Internal/Client Use Only | Strictly Confidential 20-031233-01 | Public | This work was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the international quality standard for Market Research, ISO 20252, and with the Ipsos MORI Terms and Conditions which can be found at http://www.ipsos-mori.com/terms. © Ipsos MORI Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Did behaviours change? .................................................................................................................. 5 2. Why did behaviours change? .......................................................................................................... 6 3. What next? ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 8 Survey methodology ............................................................................................................................ 8 Fieldwork dates, ‘lockdown’ restrictions and reference periods ..................................................... 9 Modes of transport ............................................................................................................................