The Price of a Cup of Tea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Superbrands 2019 Top 10 Consumer Superbrands Relevancy

Consumer Superbrands 2019 Top 10 Consumer Superbrands BRAND CATEGORY LEGO 1 Child Products - Toys and Education Apple 2 Technology - General Gillette 3 Toiletries - Men's Grooming Rolex 4 Watches British Airways 5 Travel - Airlines Coca-Cola 6 Drinks - Non-Alcoholic - Carbonated Soft Drinks Andrex 7 Household - Kitchen Rolls, Toilet Roll and Tissues Mastercard 8 Financial - General Visa 9 Financial - General Dyson 10 Household & Personal Care Appliances Relevancy Index Top 20 BRAND CATEGORY Amazon 1 Retail - Entertainment & Gifts Aldi 2 Retail - Food & Drink Macmillan Cancer Support 3 Charities Netflix 4 Media - TV Google 5 Social, Search & Comparison Sites Lidl 6 Retail - Food & Drink PayPal 7 Financial - General LEGO 8 Child Products - Toys and Education Samsung 9 Technology - General YouTube 10 Social, Search & Comparison Sites Visa 11 Financial - General Heathrow 12 Travel - Airports Purplebricks 13 Real Estate Cancer Research UK 14 Charities Oral-B 15 Toiletries - Oral Care Apple 16 Technology - General Dyson 17 Household & Personal Care Appliances TripAdvisor 18 Travel - Agents & Tour Operators Nike 19 Sportswear & Equipment Disney 20 Child Products - Toys and Education continues... Consumer Superbrands 2019 Category Winners CATEGORY BRAND Automotive - Products Michelin Automotive - Services AA Automotive - Vehicle Manufacturer Mercedes-Benz Charities Cancer Research UK Child Products - Buggies, Seats and Cots Mamas & Papas Child Products - General JOHNSON'S Child Products - Toys and Education LEGO Drinks - Alcoholic - Beer, Ale -

Evaluation of Tea and Spent Tea Leaves As Additives for Their Use in Ruminant Diets School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Deve

Evaluation of tea and spent tea leaves as additives for their use in ruminant diets The thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diky Ramdani Bachelor of Animal Husbandry, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia Master of Animal Studies, University of Queensland, Australia School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom October, 2014 Declaration I confirm that the work undertaken and written in this thesis is my own work that it has not been submitted in any previous degree application. All quoted materials are clearly distinguished by citation marks and source of references are acknowledged. The articles published in a peer review journal and conference proceedings from the thesis are listed below: Journal Ramdani, D., Chaudhry, A.S. and Seal, C.J. (2013) 'Chemical composition, plant secondary metabolites, and minerals of green and black teas and the effect of different tea-to-water ratios during their extraction on the composition of their spent leaves as potential additives for ruminants', Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61(20): 4961-4967. Proceedings Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012a) ‘Simultaneous HPLC analysis of alkaloid and phenolic compounds in green and black teas (Camellia sinensis var. Assamica)’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. 60. Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012b) ‘Effect of different tea-to-water ratios on proximate, fibre, and secondary metabolite compositions of spent tea leaves as a potential ruminant feed additive’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. -

Annual Review 1985

Unilever in 1985 ANNUAL REPORT AND SALIENT FIGURES Unilever in 1985 Annual Report and Salient Figures 1 UNILEVER N.V. ANNUAL REPORT 1985 AND SALIENT FIGURES Contents Page Unilever 2 Financial highlights 3 The Board 4 Foreword 5 Directors’ report - general 6 - review by regions 9 - review by operations - other subjects :i!i Salient figures 31 Capital and listing 39 Dates for dividend and interest payments 39 Introduction The first part of this booklet comprises an English translation of the Unilever N.V. Directors’ Report for 1985, preceded by a foreword from the Chairmen of the two Unilever parent companies. The second part, entitled ‘Salient Figures’, contains extracts from the combined consolidated annual accounts 1985 of Unilever N.V. and Unilever PLC, comparative figures for earlier years, and further information of interest to shareholders. Except where stated otherwise, currency figures in tCis booklet are expressed in guilders and are for N.V. and PLC combined. The complete Unilever N.V. annual accounts for 1985, together with the auditors’ report thereon and some additional information, are contained in a separate publication in Dutch, which is also available in an English translation entitled Unilever in 1985, Annual Accounts’. That booklet comprises the annual accounts expressed in guilders of N.V. and the N.V. Group, the PLC Group, and the combined N.V. and PLC Groups. The original Dutch versions of the two booklets mentioned above together comprise the complete annual report and accounts and further statutory information, as drawn up by the Board of Directors of Unilever N.V. in accordance with Dutch legislation. -

Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hosei University Repository Tea Drinking Culture in Russia 著者 Morinaga Takako 出版者 Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University journal or Journal of International Economic Studies publication title volume 32 page range 57-74 year 2018-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10114/13901 Journal of International Economic Studies (2018), No.32, 57‒74 ©2018 The Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University Tea Drinking Culture in Russia Takako Morinaga Ritsumeikan University Abstract This paper clarifies the multi-faceted adoption process of tea in Russia from the seventeenth till nineteenth century. Socio-cultural history of tea had not been well-studied field in the Soviet historiography, but in the recent years, some of historians work on this theme because of the diversification of subjects in the Russian historiography. The paper provides an overview of early encounters of tea in Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, comparing with other beverages that were drunk at that time. The paper sheds light on the two supply routes of tea to Russia, one from Mongolia and China, and the other from Europe. Drinking of brick tea did not become a custom in the 18th century, but tea consumption had bloomed since 19th century, rapidly increasing the import of tea. The main part of the paper clarifies how Russian- Chines trade at Khakhta had been interrelated to the consumption of tea in Russia. Finally, the paper shows how the Russian tea culture formation followed a different path from that of the tea culture of Europe. -

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04

Tea - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04 Tea From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tea is the agricultural product of the leaves, leaf buds, and internodes of the Camellia sinensis plant, prepared and cured by various methods. "Tea" also refers to the aromatic beverage prepared from the cured leaves by combination with hot or boiling water,[1] and is the common name for the Camellia sinensis plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely-consumed beverage in the world.[2] It has a cooling, slightly bitter, astringent flavour which many enjoy.[3] The four types of tea most commonly found on the market are black tea, oolong tea, green tea and white tea,[4] all of which can be made from the same bushes, processed differently, and in the case of fine white tea grown differently. Pu-erh tea, a post-fermented tea, is also often classified as amongst the most popular types of tea.[5] Green Tea leaves in a Chinese The term "herbal tea" usually refers to an infusion or tisane of gaiwan. leaves, flowers, fruit, herbs or other plant material that contains no Camellia sinensis.[6] The term "red tea" either refers to an infusion made from the South African rooibos plant, also containing no Camellia sinensis, or, in Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other East Asian languages, refers to black tea. Contents 1 Traditional Chinese Tea Cultivation and Technologies 2 Processing and classification A tea bush. 3 Blending and additives 4 Content 5 Origin and history 5.1 Origin myths 5.2 China 5.3 Japan 5.4 Korea 5.5 Taiwan 5.6 Thailand 5.7 Vietnam 5.8 Tea spreads to the world 5.9 United Kingdom Plantation workers picking tea in 5.10 United States of America Tanzania. -

BAB 2 LANDASAN TEORI 2.1 Tinjauan Data 2.1.1 Pengertian Teh

BAB 2 LANDASAN TEORI 2.1 Tinjauan Data 2.1.1 Pengertian Teh Teh adalah minuman yang mengandung kafein, sebuah minuman yang dibuat dengan cara menyeduh daun, pucuk daun, atau tangkai daun yang di keringkan dari tanaman Camellia sinensis dengan air panas. Teh merupakan minuman yang sudah dikenal dengan luas di Indonesia maupun di dunia. Minuman teh ini umum menjadi minuman sehari-hari. Karena aromanya yang harum serta rasanya yang khas membuat minuman ini banyak dikonsumsi. Namun banyak masyarakat yang kurang mengetahui tentang kelebihan dari minuman tersebut. Manfaat teh antara lain adalah sebagai antioksidan bagi tubuh manusia, dapat memperbaiki sel- sel yang rusak, menghaluskan kulit, melarutkan lemak, mencegah kanker, mencegah penyakit jantung, mengurangi kolesterol dalam darah, dan menghilangkan kantuk. Teh melati merupakan jenis teh yang paling populer di Indonesia. Konsumsi teh di Indonesia sebesar 0,8 kilogram per kapita per tahun masih jauh di bawah negara-negara lain di dunia, walaupun Indonesia merupakan negara penghasil teh terbesar nomor lima di dunia. 2.1.2 Sejarah Teh di Indonesia Tanaman penghasil teh ( Camellia sinensis ) pertama kali masuk ke Indonesia tahun 1684, berupa biji teh dari Jepang yang di bawa oleh seorang berkebangsaan Jerman bernama Andreas Cleyer, dan ditanam sebagai hiasan di Batavia. F. Valentijn, seorang rahib, juga melaporkan tahun 1694, bahwa ia melihat tanaman teh sinensis di halaman rumah gubernur jendral VOC Camphuys, di Batavia. Pada abad ke-18 muali berdiri pabrik-pabrik pengolahan (pengemasan) teh dan di dukung VOC. Setelah berakhirnya pemerintahan Inggris di Nusantara, pemerintahan Hindia Belanda mendirikan Kebun Raya Bogor sebagai kebun botani (1817). Pada tahun 1826 tanaman teh melengkapi koleksi Kebun Raya, diikuti pada tahun 1827 di Kebun 3 4 Percobaan Cisurupan, Garut, Jawa Barat. -

FDA OTC Reviews Summary of Back Issues

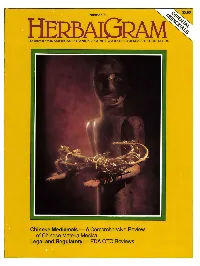

Number 23 The Journal of the AMERICAN BOTANI CAL COUNCIL and the HERB RESEARCH FOUNDATION Chinese Medicinals -A Comprehensive Review of Chinese Materia Medica Legal and Regulatory- FDA OTC Reviews Summary of Back Issues Ongoing Market Report, Research Reviews (glimpses of studies published in over a dozen scientific and technical journals), Access, Book Reviews, Calendar, Legal and Regulatory, Herb Blurbs and Potpourri columns. #1 -Summer 83 (4 pp.) Eucalyptus Repels Reas, Stones Koalas; FDA OTC tiveness; Fungal Studies; More Polysaccharides; Recent Research on Ginseng; Heart Panel Reviews Menstrual & Aphrodisiac Herbs; Tabasco Toxicity?; Garlic Odor Peppers; Yew Continues to Amaze; Licorice O.D. Prevention; Ginseng in Perspec Repels Deer; and more. tive; Poisonous Plants Update; Medicinal Plant Conservation Project; 1989 Oberly #2- Fall/Winter 83-84 (8 pp.) Appeals Court Overrules FDA on Food Safety; Award Nominations; Trends in Self-Care Conference; License Plates to Fund Native FDA Magazine Pans Herbs; Beware of Bay Leaves; Tiny Tree: Cancer Cure?; Plant Manual; and more. Comfrey Tea Recall; plus. #17-Summer 88. (24 pp.) Sarsaparilla, A Literature Review by Christopher #3-Spring 84 (8 pp.) Celestial Sells to Kraft; Rowers and Dinosaurs Demise?; Hobbs; Hops May Help Metabolize Toxins; Herbal Roach Killer; Epazote Getting Citrus Peels for Kitty Litter; Saffron; Antibacterial Sassafras; WHO Studies Anti· More Popular, Aloe Market Levels Off; Herbal Tick Repellent?; Chinese Herb fertility Plants; Chinese Herbal Drugs; Feverfew Migraines; -

Rishi Tea Debuts Organic & Fair Trade Certifiedtm Tea Bags, Featuring

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Rishi Tea debuts Organic & Fair Trade CertifiedTM Tea Bags, Featuring the Latest Innovation in Specialty Tea 2012 NATIONAL RESTAURANT ASSOCIATION SHOW Milwaukee, Wisconsin April 13, 2012: Rishi Tea (www.rishi-tea.com), leading international purveyor of organic and Fair Trade CertifiedTM loose-leaf teas, introduces its first line of specialty tea bags. Rishi Tea is first to market with an innovative knit-mesh filter bag that imparts a level of flavor, aroma and body, which standard paper or silky tea bags cannot match. Debuting at the National Restaurant Association Show in Chicago, Rishi Teaʼs organic tea bags highlight the latest innovation in the tea industry with aims to elevate the quality of the tea bag market. “Weʼre excited to introduce tea lovers to the fullest flavors and most aromatic, vivid infusions theyʼve ever experienced from a tea bag. Rishi Tea offers a new filter mesh material from plant based resources that yields a far greater extraction ratio and infusion quality than any other tea bag. Paper and even fine mesh silky bag materials are too tightly woven and act as a barrier to the tealeavesʼ infusion. We found a looser weave was needed to improve the overall tea bag experience in restaurants and foodservice at a cost per bag that meets or beats the current silky tea bag brands.” Says Joshua Kaiser, Founder and President, Rishi Tea. Available now, for Restaurants, Hotels and Food Service, 10 organic tea bags flavors: Jade Cloud Green Tea, Jasmine Green Tea, Earl Grey, Pu-erh Ginger, Blueberry Rooibos, Peppermint Rooibos, Chamomile Medley, Tropical Hibiscus & Turmeric Lemon Each organic tea bag is individually sealed in a tastefully designed, printed overwrap that maintains optimum freshness. -

2019 – Spring Newsletter

News From Red Hill Published By the Patrick Henry Memorial Foundation — Brookneal, VA Ribbon Cutting and Grand Opening On April 26th, the long-awaited day finally arrived for the grand unveiling of Red Hill’s newly completed Eugene B. Casey Education and Events Center. Celebrations began Thursday evening with a VIP preview of the building for members of the Patrick Henry Descendants’ Branch and special guests. Friday marked the main event with the official ribbon cutting and a catered party and presentations in (continued on page 2) Celebrating The Life of In This Issue... Mrs. Edith Poindexter On the morning of March including her son Cole Poindexter, Red Hill Collection 11, 2019, Edith Cabaniss Poindexter, who has inherited her role as Henry Page 3 91, went to be with her husband Geneaologist. Ms. Marstin shared Jack Robinson Poindexter. that Miz P., “told me many times PHDB Reunion Edith Poindexter—or Miz she wanted some of her ashes to be Page 4 P., as she was affectionately known scattered at this place so precious to at Red Hill—was honored at a cel- her. She deserves to be here, she has Living History Series ebration of life ceremony at the Red earned the right to be here, and I am Page 4 Hill Scatter Garden on April 26th. so happy she will always be a part Those gathered together were able of Patrick Henry’s Red Hill. Let our Alexi Garrett Essay to share stories and memories of the hearts find comfort in this and let Page 6 formidable woman and historian us hold onto our memories of her as whose work was so vital to Red Hill precious gifts.” Faces of Red Hill for many, many years. -

CONTACT US Call Your Local Depot, Or Register Online with Our Easy to Use Website That Works Perfectly on Whatever Device You Use

CONTACT US Call your local depot, or register online with our easy to use website that works perfectly on whatever device you use. Basingstoke 0370 3663 800 Nottingham 0370 3663 420 Battersea 0370 3663 500 Oban 0163 1569 100 Bicester 0370 3663 285 Paddock Wood 0370 3663 670 Birmingham 0370 3663 460 Salisbury 0370 3663 650 Chepstow 0370 3663 295 Slough 0370 3663 250 Edinburgh 0370 3663 480 Stowmarket 0370 3663 360 Gateshead 0370 3663 450 Swansea 0370 3663 230 Harlow 0370 3663 520 Wakefield 0370 3663 400 Lee Mill 0370 3663 600 Worthing 0370 3663 580 Manchester 0370 3663 400 Bidvest Foodservice 814 Leigh Road Slough SL1 4BD Tel: +44 (0)370 3663 100 http://www.bidvest.co.uk www.bidvest.co.uk Bidvest Foodservice is a trading name of BFS Group Limited (registered number 239718) whose registered office is at 814 Leigh Road, Slough SL1 4BD. The little book of TEA 3 Contents It’s Tea Time! With a profit margin of around 90%*, tea is big business. We have created this guide to tea so help you make the most of this exciting opportunity. Tea Varieties .............................. 4 Tea Formats ............................... 6 With new blends and infusions such as Chai and Which Tea Is Right For You? .... 8 Matcha as well as traditional classics such as Earl Profit Opportunity ....................10 Grey and English Breakfast, we have something for Maximise Your Tea Sales .......12 all, helping to ensure your customers’ tea experience The Perfect Serve ....................15 The Perfect Display .................16 will be a talking point! The Perfect Pairing ..................18 Tea & Biscuit Pairing ...............20 Tea Geekery ............................21 Recipes .....................................22 Tea Listing ................................28 4 People’s passion for tea All about tea has been re-ignited. -

Unilever Commits to Sourcing All Its Tea from Sustainable Ethical Sources

Unilever commits to sourcing all its tea fr... http://www.unilever.com/ourcompany/newsandm... feel good, look good and get more out of life Unilever commits to sourcing all its tea from sustainable ethical sources 25/05/2007 : Up to 2 mllion people around the world to benefit from better crops, better incomes and better livelihoods. Unilever, the world's largest tea company, is to revolutionise the tea industry by committing to purchase all its tea from sustainable, ethical sources. It has asked the international environmental NGO, Rainforest Alliance, to start by certifying tea farms in Africa. Lipton, the world's best-selling tea brand, and PG Tips, the UK's No.1 tea, will be the first brands to contain certified tea. The company aims to have all Lipton Yellow Label and PG Tips tea bags sold in Western Europe certified by 2010 and all Lipton tea bags sold globally by 2015. This is the first time a major tea company has committed to introducing sustainably certified tea on such a large scale and the first time the Rainforest Alliance, better known for coffee certification, has audited tea farms. Announcing the move in a speech to MBA students at INSEAD in Fontainebleau, France, today (25 May 2007), Unilever CEO Patrick Cescau said: "This decision will transform the tea industry, which has been suffering for many years from oversupply and underperformance. It will not be achieved overnight, but we are committed to doing it because we believe it is the right thing to do for the people who drink our tea, the people along the entire length of our supply chain and for our business. -

Annual Report 2011-12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Creating a better future every day HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED Registered Office: Unilever House, B D Sawant Marg, Chakala, Andheri East, Mumbai 400099 Hindustan www.hul.co.in U nilever nilever L imited Annual Report 2011-12 AwARDS AND FELICITATIONS WINNING WITH BRANDS AND WINNING THROUGH CONTINUOUS SUSTAINABILITY OUR MISSION INNOVATION IMPROVEMENT HUL has won the Asian Centre for Six of our brands (Lux, Lifebuoy, Closeup, HUL was awarded the FMCG Supply Corporate Governance and Sustainability Fair & Lovely, Clinic Plus and Sunsilk) Chain Excellence Award at the 5th Awards in the category ‘Company with the featured in Top 15 list in Brand Equity’s Express, Logistics & Supply Chain Awards Best CSR and Sustainability Practices.’ WE WORK TO CREATE A BETTER FUTURE Most Trusted Brands Survey. endorsed by The Economic Times along Our instant Tea Factory, Etah bagged the with the Business India Group. EVERY DAY. Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) was second prize in tea category for Energy awarded the CNBC AWAAZ Storyboard Doomdooma factory won the Gold Award Conservation from Ministry of Power, We help people feel good, look good and get more out Consumer Awards 2011 in three in the Process Sector, Large Business Govt. of India. categories. category at The Economic Times India HUL won the prestigious ‘Golden Peacock Manufacturing Excellence Awards 2011. of life with brands and services that are good for them • FMCG Company of the Year Global Award for Corporate Social and good for others. • The Most Consumer Conscious Responsibility’ for the year 2011. Company of the Year WINNING WITH PEOPLE HUL’s Andheri campus received • The Digital Marketer of the Year We will inspire people to take small, everyday actions HUL was ranked the No.1 Employer of certification of LEED India Gold in ‘New HUL won the ‘Golden Peacock Innovative Choice for students in the annual Nielsen Construction’ category, by Indian Green that can add up to a big difference for the world.