Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review on Herbal Teas

Chandini Ravikumar /J. Pharm. Sci. & Res. Vol. 6(5), 2014, 236-238 Review on Herbal Teas Chandini Ravikumar BDS Student, Savitha Dental College, Chennai Abstract: Herbal tea is essentially an herbal mixture made from leaves, seeds and/ or roots of various plants. As per popular misconception, they are not derived from the usual tea plants, but rather from what are called as ‘tisanes’. There are several kinds of tisanes (herbal teas) that have been used for their medicinal properties. Some of them being consumed for its energizing properties to help induce relaxation, to curb stomach or digestive problems and also strengthen the immune system. Some of the popular herbal teas are Black tea, Green tea, Chamomile tea, Ginger tea, Ginseng tea, Peppermint tea, Cinnamon tea etc. Some of these herbal teas possess extremely strong medicinal benefits such as, Astragalus tea, a Chinese native herb that is used for its anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial properties; which in many cases helps people living with HIV and AIDS. Demonstrating very few demerits, researchers continue to examine and vouch for the health benefits of drinking herbal teas. Key words:Camellia Sinensis, tisanes, types, medical benefits, ability to cure various ailments, advantages, disadvantages. INTRODUCTION: Herbal tea, according to many, look like tea and is brewed as the same way as tea, but in reality it is not considered a tea at all. This is due to the fact that they do not originate from the Camellia Sinensis bush, the plant from which all teas are made [1]. Herbal teas are actually mixtures of several ingredients, and are more accurately known as‘tisanes.’ Tisanes are made from combinations of dried leaves, seeds, grasses, nuts, barks, fruits, flowers, or other botanical elements that give them their taste and provide Image 1: Green tea the benefits of herbal teas [2]. -

Tea of Life® Products Collection Semi Contra

TEA OF LIFE® PRODUCTS COLLECTION SEMI CONTRA/EPAZOTE TEABAGS CHENOPODIUM AMBROSIOIDES otherwise called Semi-Contra, Epazote, American Wormseed, and Mexican Tea etc. is a remarkable natural herb that has long been used in various areas of the world for its many health benefits. The beneficial uses of plants go back to the Garden of Eden. Plants have been used since then for food and medicine, and therefore for health and well being. This fact has been preserved for generations. Your Great Grandparents knew best. There was a secret and something special in this herb, Semi- Contra. Continue the legacy they knew. Preserve for your generation, nature’s natural resource for a healthy living. Embrace the privilege of a Miracle Within Reach, Semi-Contra! TEA OF LIFE ® HEALTH INC. SPECIALIZES IN MARKETING THIS PATENTED, 100% NATURAL HERBAL GREEN TEA WITH MEDICINAL PROPERTIES. This herb has been used since the 1800’S for its Benefits in Promoting Health and Wellness being. In the 1800’s many of its benefits had been re-enforced through common uses by Yucatan Indians who used it in their cooking and folk remedies for their everyday Healing and Well being. In Late 1800’S, A German Pharmacist who was traveling in Brazil discovered from his own research and observations, remarkable findings about this herb. He observed that this herb which grew locally was used regularly by that ethnic culture for its many benefits, in promoting health. In later years this herb was re- discovered in the Caribbean, Africa, Mexico, Latin and Central America. Those cultures used the herb widely as a Dietary Supplement for its health benefits, especially in fighting off Intestinal Parasites. -

Evaluation of Tea and Spent Tea Leaves As Additives for Their Use in Ruminant Diets School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Deve

Evaluation of tea and spent tea leaves as additives for their use in ruminant diets The thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diky Ramdani Bachelor of Animal Husbandry, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia Master of Animal Studies, University of Queensland, Australia School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom October, 2014 Declaration I confirm that the work undertaken and written in this thesis is my own work that it has not been submitted in any previous degree application. All quoted materials are clearly distinguished by citation marks and source of references are acknowledged. The articles published in a peer review journal and conference proceedings from the thesis are listed below: Journal Ramdani, D., Chaudhry, A.S. and Seal, C.J. (2013) 'Chemical composition, plant secondary metabolites, and minerals of green and black teas and the effect of different tea-to-water ratios during their extraction on the composition of their spent leaves as potential additives for ruminants', Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61(20): 4961-4967. Proceedings Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012a) ‘Simultaneous HPLC analysis of alkaloid and phenolic compounds in green and black teas (Camellia sinensis var. Assamica)’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. 60. Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012b) ‘Effect of different tea-to-water ratios on proximate, fibre, and secondary metabolite compositions of spent tea leaves as a potential ruminant feed additive’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. -

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04

Tea - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04 Tea From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tea is the agricultural product of the leaves, leaf buds, and internodes of the Camellia sinensis plant, prepared and cured by various methods. "Tea" also refers to the aromatic beverage prepared from the cured leaves by combination with hot or boiling water,[1] and is the common name for the Camellia sinensis plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely-consumed beverage in the world.[2] It has a cooling, slightly bitter, astringent flavour which many enjoy.[3] The four types of tea most commonly found on the market are black tea, oolong tea, green tea and white tea,[4] all of which can be made from the same bushes, processed differently, and in the case of fine white tea grown differently. Pu-erh tea, a post-fermented tea, is also often classified as amongst the most popular types of tea.[5] Green Tea leaves in a Chinese The term "herbal tea" usually refers to an infusion or tisane of gaiwan. leaves, flowers, fruit, herbs or other plant material that contains no Camellia sinensis.[6] The term "red tea" either refers to an infusion made from the South African rooibos plant, also containing no Camellia sinensis, or, in Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other East Asian languages, refers to black tea. Contents 1 Traditional Chinese Tea Cultivation and Technologies 2 Processing and classification A tea bush. 3 Blending and additives 4 Content 5 Origin and history 5.1 Origin myths 5.2 China 5.3 Japan 5.4 Korea 5.5 Taiwan 5.6 Thailand 5.7 Vietnam 5.8 Tea spreads to the world 5.9 United Kingdom Plantation workers picking tea in 5.10 United States of America Tanzania. -

Final Report

Detail Study of Self-Reliant Industrial Goods in Nepal Final Report Submitted To: Government of Nepal Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies Department of Industry Tripureswor, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted By: Quality & Environmental Management Service Pvt. Ltd. Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone-01-5705455, E-mail- [email protected] June, 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Quality and Environmental Management Service Pvt. Ltd. takes an opportunity to express its’ gratitude to those Experts/stakeholders who contributed their valuable time and added precious value in this study. Particularly it extends sincere appreciation to Mr. Jiblal Bhusal, Director General, Mr. Krishna Prasad Kharel, Director; Mr. Pushpa Raj Shiwakoti, Statistical Officer, Mr. Santosh Koirala Mechanical Engineer and others staff of the Department of Industry for their kind inputs and guidance to bring this report to the final stage. We would also like to appreciate for the time and inputs of Mr. Jiblal Kharel Board member of Nepal Tea and Coffee Development Board (NTCDB), Mr. Naresh Katwal Chairperson of Federation of Nepalese Business Association, Mr. Dilli Baskota Member Sectary of HOTPA, Mr. Asish Sigdel Chairperson of NEEMA, Mr. Chandra khadgi member Sectary of NPMA, Mr Suresh Mittal Chairperson NTPA Jhapa and Mr. Rudra Prasad Neupane Board Member of FMAN. We would also like to thank for valuable input from Mr. Bikash Keyal Director of Narayani Strips Pvt. Ltd, Mr. A.K Jha GM of Hulas Steel Pvt. Ltd, Mr. Dibya Sapkota GM of Aarati Strip Pvt. Ltd., Mr Devendra Sahoo GM of Panchakanya Steel Pvt. Ltd, Mr. Laxman Aryal Chairperson of Jasmin Paints Pvt. Ltd. Mr.Buddhi Bahadur K.C chairperson of Applo Paints Pvt. -

A Russian Tea Wedding an Interview with Katya & Denis

Voices from the Hut A Russian Tea Wedding An Interview with Katya & Denis This growing community often blows our hearts wide open. It is the reason we feel so inspired to publish these magazines, build centers and host tea ceremonies: tea family! Connection between hearts is going to heal this world, one bowl at a time... Katya & Denis are tea family to us all, and so let’s share in the occasion and be distant witnesses at their beautiful tea wedding! 茶道 ne of the things we love the imagine this continuing in so many dinner, there was a party for the Bud- O most about Global Tea Hut is beautiful ways! dhists on the tour and Denis invited the growing community, and all the We very much want to foster Katya to share some puerh with him. beautiful family we’ve made through community here, and way beyond It was the first time she’d ever tried tea. As time passes, this aspect of be- just promoting our tea tradition. It such tea, and she loved it from the ing here, sharing tea with all of you, doesn’t matter if you practice tea in first sip. Then, in 2010, Katya moved starts to grow. New branches sprout our tradition or not, we’re family—in from her birthplace in Siberia, every week, and we hear about new our love for tea, Mother Earth and Komsomolsk-na-Amure, to Moscow and amazing ways that members are each other! If any of you have any to live with Denis (her hometown is connecting to each other. -

What Every Dentist Should Know About Tea

Nutrition What every dentist should know about tea Moshe M. Rechthand n Judith A. Porter, DDS, EdD, FICD n Nasir Bashirelahi, PhD Tea is one of the most frequently consumed beverages in the world, of drinking tea, as well as the potential negative aspects of tea second only to water. Repeated media coverage about the positive consumption. health benefits of tea has renewed interest in the beverage, particularly Received: August 23, 2013 among Americans. This article reviews the general and specific benefits Accepted: October 1, 2013 ea has been a staple of Chinese life for their original form.4 Epigallocatechin-3- known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) so long that it is considered to be 1 of galate (EGCG) is the principal bioactive are formed through normal aerobic cellular Tthe 7 necessities of Chinese culture.1 catechin left intact in green tea and the metabolism. During this process, oxygen is The popularity of tea should come as no one responsible for many of its health partially reduced to form a reactive radical surprise considering the recent studies benefits.3 By contrast, black tea is fully as a byproduct in the formation of water. conducted confirming tea’s remarkable oxidized/fermented during processing, ROS are helpful to the body because they health benefits.2,3 The drinking of tea dates which accounts for both its stronger flavor assist in the degradation of microbial back to the third millenium BCE, when and the fact that its catechin content is disease.5 However, ROS also contain free Shen Nong, the famous Chinese emperor lower than the other teas.2 Black tea’s fer- radical electrons that can wreak havoc on and herbalist, discovered the special brew. -

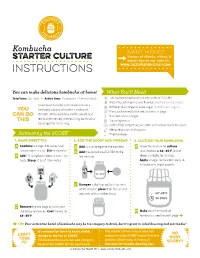

Instructions for Making Kombucha

Kombucha Want more? Dozens of eBooks, videos, & starter culture expert tips on our website: www.culturesforhealth.com Instructions m R You can make delicious kombucha at home! What You’ll Need Total time: 30+ days _ Active time: 15 minutes + 1 minute daily 1 dehydrated kombucha starter culture (SCOBY) Water free of chlorine and fluoride (bottled spring water) A kombucha starter culture consists of a sugar White or plain organic cane sugar (avoid harsh sugars) symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast you Plain, unflavored black tea, loose or in bags (SCOBY). When combined with sweetened can do Distilled white vinegar tea and fermented, the resulting kombucha this 1 quart glass jar beverage has a tart zing. Coffee filter or tight-weave cloth and rubber band to secure Measuring cups and spoons Activating the SCOBY Thermometer 1. make sweet tea 2. add the scoby and vinegar 3. culture your kombucha A Combine 2-3 cups hot water and G Allow the mixture to > >D Add 1/2 cup vinegar to the cool tea. > culture 1/4 cup sugar in a jar. Stir to dissolve. undisturbed at 68°-85°F, out of >E Add the dehydrated SCOBY to the B 11/2 teaspoons loose tea or 2 tea direct sunlight, for 30 days. > Add tea mixture. bags. Steep at least 10 minutes. Apply vinegar to the cloth daily to help prevent mold growth. sugar 1/2 1/4 c. c. 68°-85°F 2-3 c. 2 F Dampen a cloth or coffee filter with > white vinegar; place it on the jar and secure it with a rubber band. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

Still Life: Tea Set

Language through Art: An ESL Enrichment Curriculum (Beginning) Information for Teaching Still Life: Tea Set Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702–89) About 1781–83 Oil on canvas mounted on board 14 7/8 x 20 5/16 in. 84.PA.57 Background Information Chinese porcelain and tea drinking were popular in Europe when Jean-Étienne Liotard was born. In this painting of teatime disarray, a tray is set with a teapot, lidded vase (perhaps containing an extra supply of tea leaves), plate of bread and butter, sugar bowl with tongs, milk jug, and six cups, saucers, and spoons. A large bowl holding a teacup and saucer could also be used for dumping the slops of cold tea and used tea leaves. By the time Liotard painted this work in the late 1700s, tea drinking had become fashionable among the middle class as well as the upper class. This is one of five known depictions of china tea sets that he created around 1783. About the Artist Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702–89) Liotard first trained as a painter in Geneva. While in his twenties, he sought his fortune in Paris, where he studied in a prominent painter's studio. Later he traveled to Italy and throughout the Mediterranean region and finally settled in Constantinople for four years. Intrigued by the native dress, he grew a long beard and acquired the habit of dressing as a Turk, earning himself the nickname "the Turkish painter." While in Constantinople, he painted portraits of members of the British colony. For the remainder of his life, Liotard traveled throughout Europe painting portraits in pastels. -

Growing an Herbal Tea Garden

Growing an Herbal Tea Garden By Lynn Heagney March 1, 2019 Teas if you please Growing an herbal tea garden is fun and rewarding. It involves selecting the site for your garden, deciding which herbs you’d like to grow, choosing a design, then planting, harvesting, and using the herbs you’ve grown in delicious teas. When you’re finished, not only will you have a wonderful source for all of your favorite teas, but you’ll also have a place that attracts butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds. Your first major decision is deciding where you’d like to locate your garden. Be sure to pick a site that has lots of sun, at least 4-6 hours per day because most herbs like sunny locations. Also, pick an area that drains well. Only mint likes “wet feet;” the rest prefer drier areas. If your only option is a damp area, you might consider planting your herbs in a raised bed, or in containers. It’s also nice if you can find a site that’s relatively close to your house so you can have fast and easy access to fresh herbs. Now you’re ready to choose which herbs you’d like to include in your garden. You can decide to establish a site exclusively for herbs used only in teas, or you can combine those with culinary herbs. You can also mix both types of herbs with a variety of flowers. If you’d like see how these combinations might work, plan a visit to the Discovery Gardens in Mount Vernon, where the Herb Garden and Cottage Garden provide inspiring examples of these strategies. -

Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT Contentsissue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark

GL BAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 December 2018 紅 印 藍 印印 級 Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark To conclude this amazing year, we will be explor- ing the Masterpiece Era of puerh tea, from 1949 to 1972. Like all history, understanding the eras Love is of puerh provides context for today’s puerh pro- duction. These are the cakes producers hope to changing the world create. And we are, in fact, going to drink a com- memorative cake as we learn! bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 37 A Brief History of Puerh Tea Yang Kai (楊凱) 03 43 Masterpiece Era: Red Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 53 Masterpiece Era: Blue Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 37 31 Traditions傳統文章 03 Tea of the Month “Blue Mark,” 2000 Sheng Puerh, Yunnan, China 31 Gongfu Teapot Getting Started in Gongfu Tea By Shen Su (聖素) 53 61 TeaWayfarer Gordon Arkenberg, USA © 2018 by Global Tea Hut 藍 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system 印 or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, pho- tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. n December,From the weather is much cooler in Taiwan.the We This is an excitingeditor issue for me. I have always wanted to are drinking Five Element blends, shou puerh and aged find a way to take us on a tour of the eras of puerh. Puerh sheng. Occasionally, we spice things up with an aged from before 1949 is known as the “Antique Era (號級茶時 oolong or a Cliff Tea.