Small-Scale Tea Growing and Processing in Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyan in Mist

Cyan in mist --- Sustainable packaging design for Chinese tea Author: Wu Fei Linnaeus University Faculty of Arts and Humanities Design, Master Program, 2nd year Supervisor: Johan Vaide , Petra Lilja , Fredrik Sandberg; Opponent: Sara Hyltén- Cavallius, Ola Ståhl Examiner: Lars Dafnäs Date of examination:May 17th, 2016 1 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to foremost thank all the designers and marketers who took their time to participate in my study. I truly appreciate your time and provision of insights. I would also like to thank my supervisor, Johan Vaide, Ola Ståhl, who guided me and kept us on course throughout the entire writing process. Fredrik Sandberg, Petra Lilja, who has given sincere support and advice throughout the project. 2 Abstract Packaging is a topic under debate and scrutiny in today’s society, due to its obvious environmental detriment – but also the business opportunities – tied to minimizing or even eliminating packaging. therefore, in this thesis, the aim is to introduce Chinese tea culture to the Swedish through packaging design, By tea culture studies and surveys of the Swedish market, with less is more, and minimalism design theory to design elegant and Sustainable package. With this design, convey the Chinese tea ceremony culture and Zen philosophy. Through the study of Chinese tea culture, then analysis current tea packaging on Chinese and Swedish markets, from the structure, color, material…every aspects of packaging design to show the Chinese tea culture in the Swedish market. 3 According to our respondents and theory, packaging is a big component in a brand's marketing strategy and to communicate the brand’s message and values. -

Evaluation of Tea and Spent Tea Leaves As Additives for Their Use in Ruminant Diets School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Deve

Evaluation of tea and spent tea leaves as additives for their use in ruminant diets The thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diky Ramdani Bachelor of Animal Husbandry, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia Master of Animal Studies, University of Queensland, Australia School of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development Newcastle University Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom October, 2014 Declaration I confirm that the work undertaken and written in this thesis is my own work that it has not been submitted in any previous degree application. All quoted materials are clearly distinguished by citation marks and source of references are acknowledged. The articles published in a peer review journal and conference proceedings from the thesis are listed below: Journal Ramdani, D., Chaudhry, A.S. and Seal, C.J. (2013) 'Chemical composition, plant secondary metabolites, and minerals of green and black teas and the effect of different tea-to-water ratios during their extraction on the composition of their spent leaves as potential additives for ruminants', Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 61(20): 4961-4967. Proceedings Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012a) ‘Simultaneous HPLC analysis of alkaloid and phenolic compounds in green and black teas (Camellia sinensis var. Assamica)’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. 60. Ramdani, D., Seal, C.J. and Chaudhry, A.S., (2012b) ‘Effect of different tea-to-water ratios on proximate, fibre, and secondary metabolite compositions of spent tea leaves as a potential ruminant feed additive’, Advances in Animal Biosciences, Proceeding of the British Society of Animal Science Annual Conference, Nottingham University, UK, April 2012, p. -

(Coffea Arabica) Beans: Chlorogenic Acid As a Potential Bioactive Compound

molecules Article Decaffeination and Neuraminidase Inhibitory Activity of Arabica Green Coffee (Coffea arabica) Beans: Chlorogenic Acid as a Potential Bioactive Compound Muchtaridi Muchtaridi 1,2,* , Dwintha Lestari 2, Nur Kusaira Khairul Ikram 3,4 , Amirah Mohd Gazzali 5 , Maywan Hariono 6 and Habibah A. Wahab 5 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Analysis and Medicinal Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jl. Bandung-Sumedang KM 21, Jatinangor 45363, Indonesia 2 Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Muhammadiyah Bandung, Jl. Soekarno-Hatta No. 752, Bandung 40614, Indonesia; [email protected] 3 Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Centre for Research in Biotechnology for Agriculture (CEBAR), Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia 5 School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, USM, Penang 11800, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.M.G.); [email protected] (H.A.W.) 6 Faculty of Pharmacy, Campus III, Sanata Dharma University, Paingan, Maguwoharjo, Depok, Sleman, Yogyakarta 55282, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +62-22-8784288888 (ext. 3210) Abstract: Coffee has been studied for its health benefits, including prevention of several chronic Citation: Muchtaridi, M.; Lestari, D.; diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cancer, Parkinson’s, and liver diseases. Chlorogenic acid Khairul Ikram, N.K.; Gazzali, A.M.; (CGA), an important component in coffee beans, was shown to possess antiviral activity against Hariono, M.; Wahab, H.A. viruses. However, the presence of caffeine in coffee beans may also cause insomnia and stomach Decaffeination and Neuraminidase irritation, and increase heart rate and respiration rate. -

Camellia Sinensis): a Review

Review articles Hepatotoxicity due to green tea consumption (Camellia Sinensis): A review Eliana Palacio Sánchez,1 Marcel Enrique Ribero Vargas,1, Juan Carlos Restrepo Gutiérrez.2 1 Student at the Medicine Faculty of the Universidad Abstract de Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia. Member of the Gastro-hepatology Group at the Universidad de As consumption of green tea has increased in recent years, so too have reports of its adverse effects. Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia Hepatotoxicity is apparently caused by enzymatic interaction that leads to cellular damage and interference 2 Internist and Hepatologist in the Hepatology and with biological response systems and metabolic reactions. This review article introduces the morphological Liver Transplant Unit of the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín, Colombia. Tenured Professor in characteristics and biochemical components of the green tea plant, camellia sinensis. Analysis of clinical trials, the Medicine Faculty of the Universidad de Antioquia in-vitro trials and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies then shed light on some of the mechanisms in Medellín, Colombia. Mail: [email protected]; by which green tea causes hepatic damage. Examples are the chemical interactions with enzymes such as [email protected] UDPGT, alcohol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P450 and interactions with the mitochondrial enzyme and ......................................... immune systems. These forms of cellular lesions are correlated with case reports in the scientific literature Received: 27-06-12 which clarify the spectrum of hepatic damage associated with the consumption of green tea. This analysis Accepted: 18-12-12 finds that even though the mechanisms by which green tea causes hepatic toxicity are still a mystery, certain catechins of camellia sinensis and interactions at the cellular and mitochondrial levels may be responsible for this toxicity. -

Pu-Erh Tea Tasting in Yunnan, China: Correlation of Drinkers’ Perceptions to Phytochemistry

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 132 (2010) 176–185 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Pu-erh tea tasting in Yunnan, China: Correlation of drinkers’ perceptions to phytochemistry a,b,c,d,e, c,f d,g a,d Selena Ahmed ∗, Uchenna Unachukwu , John Richard Stepp , Charles M. Peters , Chunlin Long d,e, Edward Kennelly b,c,d,f a Institute of Economic Botany, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458, USA b Department of Biology, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY 10016, USA c Department of Biological Sciences, Lehman College, Bronx, NY 10468, USA d School of Life and Environmental Science, Central University for Nationalities, Minzu University, 27 Zhong-Guan-Cun South Avenue, Beijing, China e Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Heilongtan, Kunming, Yunnan, China f Department of Biochemistry, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY 10016, USA g Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, 1112 Turlington Hall Gainesville, FL 32611, USA article info abstract Article history: Aim of the study: Pu-erh (or pu’er) tea tasting is a social practice that emphasizes shared sensory experience, Received 17 March 2010 wellbeing, and alertness. The present study examines how variable production and preparation practices Received in revised form 31 July 2010 of pu-erh tea affect drinkers’ perceptions, phytochemical profiles, and anti-oxidant activity. Accepted 7 August 2010 Materials and methods: One hundred semi-structured interviews were conducted in Yunnan Province to Available online 8 September 2010 understand the cultural and environmental context of pu-erh tea tasting. -

Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hosei University Repository Tea Drinking Culture in Russia 著者 Morinaga Takako 出版者 Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University journal or Journal of International Economic Studies publication title volume 32 page range 57-74 year 2018-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10114/13901 Journal of International Economic Studies (2018), No.32, 57‒74 ©2018 The Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University Tea Drinking Culture in Russia Takako Morinaga Ritsumeikan University Abstract This paper clarifies the multi-faceted adoption process of tea in Russia from the seventeenth till nineteenth century. Socio-cultural history of tea had not been well-studied field in the Soviet historiography, but in the recent years, some of historians work on this theme because of the diversification of subjects in the Russian historiography. The paper provides an overview of early encounters of tea in Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, comparing with other beverages that were drunk at that time. The paper sheds light on the two supply routes of tea to Russia, one from Mongolia and China, and the other from Europe. Drinking of brick tea did not become a custom in the 18th century, but tea consumption had bloomed since 19th century, rapidly increasing the import of tea. The main part of the paper clarifies how Russian- Chines trade at Khakhta had been interrelated to the consumption of tea in Russia. Finally, the paper shows how the Russian tea culture formation followed a different path from that of the tea culture of Europe. -

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04

Tea - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04 Tea From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tea is the agricultural product of the leaves, leaf buds, and internodes of the Camellia sinensis plant, prepared and cured by various methods. "Tea" also refers to the aromatic beverage prepared from the cured leaves by combination with hot or boiling water,[1] and is the common name for the Camellia sinensis plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely-consumed beverage in the world.[2] It has a cooling, slightly bitter, astringent flavour which many enjoy.[3] The four types of tea most commonly found on the market are black tea, oolong tea, green tea and white tea,[4] all of which can be made from the same bushes, processed differently, and in the case of fine white tea grown differently. Pu-erh tea, a post-fermented tea, is also often classified as amongst the most popular types of tea.[5] Green Tea leaves in a Chinese The term "herbal tea" usually refers to an infusion or tisane of gaiwan. leaves, flowers, fruit, herbs or other plant material that contains no Camellia sinensis.[6] The term "red tea" either refers to an infusion made from the South African rooibos plant, also containing no Camellia sinensis, or, in Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other East Asian languages, refers to black tea. Contents 1 Traditional Chinese Tea Cultivation and Technologies 2 Processing and classification A tea bush. 3 Blending and additives 4 Content 5 Origin and history 5.1 Origin myths 5.2 China 5.3 Japan 5.4 Korea 5.5 Taiwan 5.6 Thailand 5.7 Vietnam 5.8 Tea spreads to the world 5.9 United Kingdom Plantation workers picking tea in 5.10 United States of America Tanzania. -

Final Report

Detail Study of Self-Reliant Industrial Goods in Nepal Final Report Submitted To: Government of Nepal Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies Department of Industry Tripureswor, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted By: Quality & Environmental Management Service Pvt. Ltd. Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone-01-5705455, E-mail- [email protected] June, 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Quality and Environmental Management Service Pvt. Ltd. takes an opportunity to express its’ gratitude to those Experts/stakeholders who contributed their valuable time and added precious value in this study. Particularly it extends sincere appreciation to Mr. Jiblal Bhusal, Director General, Mr. Krishna Prasad Kharel, Director; Mr. Pushpa Raj Shiwakoti, Statistical Officer, Mr. Santosh Koirala Mechanical Engineer and others staff of the Department of Industry for their kind inputs and guidance to bring this report to the final stage. We would also like to appreciate for the time and inputs of Mr. Jiblal Kharel Board member of Nepal Tea and Coffee Development Board (NTCDB), Mr. Naresh Katwal Chairperson of Federation of Nepalese Business Association, Mr. Dilli Baskota Member Sectary of HOTPA, Mr. Asish Sigdel Chairperson of NEEMA, Mr. Chandra khadgi member Sectary of NPMA, Mr Suresh Mittal Chairperson NTPA Jhapa and Mr. Rudra Prasad Neupane Board Member of FMAN. We would also like to thank for valuable input from Mr. Bikash Keyal Director of Narayani Strips Pvt. Ltd, Mr. A.K Jha GM of Hulas Steel Pvt. Ltd, Mr. Dibya Sapkota GM of Aarati Strip Pvt. Ltd., Mr Devendra Sahoo GM of Panchakanya Steel Pvt. Ltd, Mr. Laxman Aryal Chairperson of Jasmin Paints Pvt. Ltd. Mr.Buddhi Bahadur K.C chairperson of Applo Paints Pvt. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

Some Tips About Drinking Tea

Some tips about drinking tea (Zhu Li) Tea is the most popular drink in the world. Tea itself is the balance of Yin and Yang. First of all, how to categorize tea? Tea can be grouped into Yin Tea and Yang Tea. Yin Tea includes white tea, dark tea and yellow tea. Yang Tea includes green tea, black tea and qing (blue) tea. So, in total there are 6 categories of tea, 3 kinds of Yin Tea and 3 kinds of Yang Tea. Secondly, how to prepare tea? The preparation of tea follows the Yin Yang balance rule. When preparing the Yin Tea, we use the ‘Yang’ way, boiling is the easiest and best way. Comparatively, when preparing the Yang Tea, we need to choose the ‘Yin’ way, and never boil any Yang Tea, otherwise it may cause potential health problems. Boiling the Yang Tea will produce anthraquinone in green tea, cyanogenic glycosides in qing tea, and acrylamide in black tea, and all these chemical components may cause cancer in long run. So, using the clay pot to prepare black tea will not only helps us to get best taste but also a cup of healthy tea. As to Qing tea, it’s easy to use French press to prepare it. Grand Yang tea, green tea needs a special treat, which is to drop the 1 boiled water into the cup with green tea leaves. By doing this way, the green tea will taste fresh and have sweet ending. Thirdly, when to drink tea? The time consideration of tea drinking actually is related with the best time of acupuncture method, which is called ‘Zi Wu Liu Zhu’ in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). -

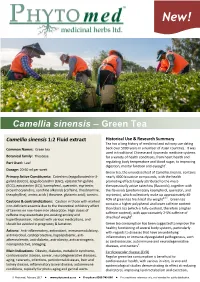

Camellia Sinensis – Green Tea

New! Photo supplied by Zealong Tea Estate Camellia sinensis – Green Tea Camellia sinensis 1:2 Fluid extract Historical Use & Research Summary Tea has a long history of medicinal and culinary use dating back over 5000 years in a number of Asian countries. It was Common Names: Green tea used in traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine systems Botanical family: Theaceae for a variety of health conditions, from heart health and Leaf regulating body temperature and blood sugar, to improving Part Used: 1 digestion, mental function and eyesight . Dosage: 20-60 ml per week Green tea, the unoxidised leaf of Camellia sinensis, contains Primary Active Constituents: Catechins (epigallocatechin-3- nearly 4000 bioactive compounds, with the health gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin gallate promoting effects largely attributed to the most- (ECG), epicatechin (EC)); kaempferol, quercetin, myricetin; therapeutically active catechins (flavanols), together with proanthocyanidins; xanthine alkaloids (caffeine, theobromine, the flavonols (predominately kaempferol, quercetin, and theophylline); amino acids ( theanine, glutamic acid); tannins. myricetin), which collectively make up approximately 30- 40% of green tea fresh leaf dry weight2,3,4. Green tea Cautions & contraindications: Caution in those with marked contains a higher polyphenol and lower caffeine content iron-deficient anaemia due to the theoretical inhibitory effect than black tea (which is fully-oxidised, therefore a higher of tannins on non-haem iron absorption. High doses of -

MATCHA 2018 • FLAVOR INSIGHT REPORT Matcha, Also Referred to As Hiki-Cha, Is a Finely Ground Powder of Specially Grown and Processed Green Tea Leaves

MATCHA 2018 • FLAVOR INSIGHT REPORT Matcha, also referred to as hiki-cha, is a finely ground powder of specially grown and processed green tea leaves. Traditionally, Japanese tea ceremonies center on the preparation, serving, and drinking of matcha. The hot tea is said to embody a meditative spiritual style. Today, matcha is also used to flavor and dye foods such as mochi and soba noodles. We’re seeing this unique taste appear in a plethora of products and recipes, from a squid ink noodle dish to flavored almond milk. Let’s take a look at the various forms of matcha green tea on the menu, in social media, and in new products. On the Food Network, 70 MATCHA recipes appear in a search Print & Social Media Highlights for matcha. Recipes include matcha blondies, matcha There are several mentions of matcha in social and print media. Here are lemonade, matcha herb some of the highlights. 70 scones, coconut matcha- cream pie, matcha steamed • While scrolling through Pinterest, matcha pins appear in a wide MATCHA RECIPES variety of food and beverage recipes, especially beverages and baked cod, no-churn matcha ice ON FOOD NETWORK goods. These pins include iced coconut matcha latte, matcha no- cream, matcha roast chicken bake energy bites, matcha chocolate bark, matcha chia pudding, with leeks and matcha and matcha overnight oats, and matcha banana donuts with matcha mushroom soup. lemon glaze. • A Twitter search shows tweets mentioning matcha, a linked recipe from @ArgemiroElPrimo for “homemade matcha green tea muffins with matcha glaze.” Also mentioned by @LeilaBuffery: a recipe for “vegan matcha green tea cake” with linked video tutorial.