9. Adventures in Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

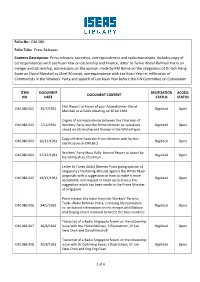

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

PEMIKIRAN SOEDJATMOKO TENTANG NASIONALISME Analisis Konten Dari Buku-Buku Karangan Soedjatmoko

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository Universitas Negeri Jakarta PEMIKIRAN SOEDJATMOKO TENTANG NASIONALISME Analisis Konten dari Buku-buku Karangan Soedjatmoko Ayu Rahayu 4115133797 Skripsi yang ditulis untuk memenuhi salah satu persyaratan dalam memperoleh gelar Sarjana Pendidikan PENDIDIKAN PANCASILA DAN KEWARGANEGARAAN FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL UNIVERSITAS NEGERI JAKARTA 2018 2 ABSTRAK AYU RAHAYU, Pemikiran Soedjatmoko tentang Nasionalisme, Analisis Konten dari Buku-buku Karangan Soedjatmoko. Skripsi. Jakarta: Program Studi Pendidikan Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Desember 2017. Penelitian ini meneliti rasa nasionalisme yang kerap digaungkan. Meski rasa nasionalisme hanya menjadi slogan semata. Orang-orang yang berbicara nasionalisme namun tidak tahu pasti arti, makna dan tindakan dari rasa Nasionalisme. Sebab, pengasahan nasionalisme dipisahkan dari sejarah bangsa. Nasionalisme tanpa melihat kembali konteks sejarah hanya menuai konflik. Untuk menghindari nasionalisme dangkal, diadakanlah penggalian gagasan dari Soedjatmoko. Penelitian ini diajukan untuk mengolah pemikiran Soedjatmoko tentang Nasionalisme. Penelitian menggunakan jenis penelitian deskriptif kualitatif. Teknik Analisis menggunakan analisis konten pada buku-buku karangan Soedjatmoko Tiga buku dipilih untuk memenuhi teknik analisis. Tiga buku karangan Soedjatmoko berjudul Kebudayaan Sosialis, Dilema Manusia dalam Pembangunan dan Pembangunan dan Kebebasan. Dari -

Daim: New Financial Hub Proposal Merits Consideration (NST 11/03

11/03/2000 Daim: New financial hub proposal merits consideration Hardev Kaur in Jakarta JAKARTA, Fri: The proposal for a new financial centre, possibly based in Bandar Seri Begawan, to facilitate financial transactions among Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, deserves serious consideration despite there being already such centres in East Asia and South-East Asia. Indonesian President Abdurrahman Wahid, who had discussed the proposal with the Sultan of Brunei recently, raised the matter during bilateral talks with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad at the Merdeka Palace yesterday. Finance Minister Tun Daim Zainuddin said details of the proposal as well as implications of the move must be studied. He was asked whether there is room for another centre, considering there are already Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre (IOFC), the Bangkok Financial Centre, Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo. "If there is business, why not?" Daim said. In fact, members of the East Asia Growth Area (EAGA) - Malaysia, Brunei Indonesia and the Philippines - have agreed that the Labuan IOFC serve as the financial centre for the grouping. Even so, the proposal should not be rejected outright, he said, adding that Indonesia and Brunei might have their reasons for suggesting it. When Malaysia decided to set up Labuan IOFC, it undertook several detailed studies including looking at operations of existing financial centres such as the one in the Cayman Islands. Daim is in the high-powered delegation accompanying Dr Mahathir on his two-day official visit here. The Finance Minister, who is also Special Functions Minister, held parallel discussions with his counterpart and the republic's other economic ministers. -

Malaysian Parliament 1965

Official Background Guide Malaysian Parliament 1965 Model United Nations at Chapel Hill XVIII February 22 – 25, 2018 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director ………………………………………………………………… 3 Letter from the Chair ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Background Information ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Background: Singapore ……………………………………………………… 5 Background: Malaysia ……………………………………………………… 9 Identity Politics ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Radical Political Parties ………………………………………………………………………… 14 Race Riots ……………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Positions List …………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Endnotes ……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Parliament of Malaysia 1965 Page 2 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Malaysian Parliament of 1965 Committee at the Model United Nations at Chapel Hill 2018 Conference! My name is Annah Bachman and I have the honor of serving as your Crisis Director. I am a third year Political Science and Philosophy double major here at UNC-Chapel Hill and have been involved with MUNCH since my freshman year. I’ve previously served as a staffer for the Democratic National Committee and as the Crisis Director for the Security Council for past MUNCH conferences. This past fall semester I studied at the National University of Singapore where my idea of the Malaysian Parliament in 1965 was formed. Through my experience of living in Singapore for a semester and studying its foreign policy, it has been fascinating to see how the “traumatic” separation of Singapore has influenced its current policies and relations with its surrounding countries. Our committee is going back in time to just before Singapore’s separation from the Malaysian peninsula to see how ethnic and racial tensions, trade policies, and good old fashioned diplomacy will unfold. Delegates should keep in mind that there is a difference between Southeast Asian diplomacy and traditional Western diplomacy (hint: think “ASEAN way”). -

Technocracy in Economic Policy-Making in Malaysia

Technocracy in Economic Policy-Making in Malaysia Khadijah Md Khalid* and Mahani Zainal Abidin** This article looks at the role of the technocracy in economic policy-making in Malay- sia. The analysis was conducted across two phases, namely the period before and after the 1997/98 economic and financial crises, and during the premiership of four prime ministers namely Tun Razak, Dr Mahathir, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, and Najib Razak. It is claimed that the technocrats played an important role in helping the political leadership achieve their objectives. The article traces the changing fortunes of the technocracy from the 1970s to the present. Under the premiership of Tun Razak, technocrats played an important role in ensuring the success of his programs. However, under Dr Mahathir, the technocrats sometimes took a back seat because their approach was not in line with some of his more visionary ventures and his unconventional approach particularly in managing the 1997/98 financial crisis. Under the leadership of both Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and Najib Razak, the technocrats regain their previous position of prominence in policy-making. In conclusion, the technocracy with their expert knowledge, have served as an important force in Malaysia. Although their approach is based on economic rationality, their skills have been effectively negotiated with the demands of the political leadership, because of which Malaysia is able to maintain both economic growth and political stability. Keywords: technocracy, the New Economic Policy (NEP), Tun Abdul Razak, Dr Mahathir Mohamad, National Economic Action Council (NEAC), government-linked companies (GLCs), Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Najib Tun Razak Introduction Malaysia is a resource rich economy that had achieved high economic growth since early 1970s until the outbreak of the Asian crisis in 1998. -

![Vol. 42 No. 3 [2016] No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9237/vol-42-no-3-2016-no-829237.webp)

Vol. 42 No. 3 [2016] No

Vol. 42 No. 3 [2016] No. 42 Vol. pointer Vol. 42 No. 3 [2016] THE JOURNAL OF THE SINGAPORE ARMED FORCES Editorial Board Advisor RADM Giam Hock Koon Chairman COL Ng Wai Kit Deputy Chairman COL(NS) Irvin Lim Members COL(NS) Tan Swee Bock COL(NS) Benedict Ang Kheng Leong COL Victor Huang COL Simon Lee Wee Chek SLTC Goh Tiong Cheng ME6 Colin Teo MAJ Charles Phua Chao Rong MS Deanne Tan Ling Hui MR Kuldip Singh MR Daryl Lee Chin Siong CWO Ng Siak Ping MR Eddie Lim Editorial Team Editor MS Helen Cheng Assistant Editor MR Bille Tan Research Specialists CPL Delson Ong LCP Jeria Kua LCP Macalino Minjoot The opinions and views expressed in this journal do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Ministry of Defence. The Editorial Board reserves the right to edit and publish selected articles according to its editorial requirements. Copyright© 2016 by the Government of the Republic of Singapore. All rights reserved. The articles in this journal are not to be reproduced in part or in whole without the consent of the Ministry of Defence. ISSN 2017-3956 Vol. 42 No. 3 [2016] contents iii EDITORIAL FEATURES 01 To What Extent can Singapore’s Maritime Security Outlook be considered as Exceptional within Southeast Asia? by LTC Daniel Koh Zhi Guo 17 Is Full Spectrum Operations a Viable Strategic Posture for the Singapore Armed Forces? by MAJ Lee Hsiang Wei 27 Cyber Attacks and the Roles the Military Can Play to Support the National Cyber Security Efforts by ME5 Alan Ho Wei Seng 38 The Future of the Singapore Armed Forces Amidst the Transforming -

Malaysia's Pathway Through Financial Crisis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Jomo Kwame Sundaram Working Paper Malaysia's pathway through financial crisis GEG Working Paper, No. 2004/08 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Oxford, Global Economic Governance Programme (GEG) Suggested Citation: Jomo Kwame Sundaram (2004) : Malaysia's pathway through financial crisis, GEG Working Paper, No. 2004/08, University of Oxford, Global Economic Governance Programme (GEG), Oxford This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/196271 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu • GLOBAL ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE PROGRAMME • Jomo K. Sundaram, GEG Working Paper 2004/08 Jomo Kwame Sundaram Jomo Kwame Sundaram (Jomo K. S.) is Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations. -

Peny Ata Rasmi Parlimen Parliamentary Debates

Jilid III Hari Isnin Bil. 10 8hb April,1985 PENY ATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PARLIMEN KEENAM Sixth Parliament PENGGAL KETIGA Third Session KANDUNGANNYA JA WAPAN-JA WAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANY AAN [Ruangan 1457] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT [Ruangan 1516] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Pembantu Hospital (Pendaftaran) (Pindaan) [Ruangan 1516] Rang Undang-undang Kanun-~n Keseksaan (Pindaan) [Ruangan 1544] Rang Undang-undang Kewangan [Ruangan 1550] Rang Undang-undang Takaful (Pindaan) [Ruangan 1552] Rang Undang-undang Perikanan [Ruangan 1556] MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT KEENAM Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG KETIGA AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAn ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pertahanan, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.N.M. (Kubang Pasu). ,, Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, DATO' MUSA HITAM, S.P.M.J., S.S.I.J., S.P.M.S., D.U.N.M., S.P.N.S. (Panti). Yang Berhormat Menteri Perumahan dan Kerajaan Tempatan, DATO' DR NEo YEE PAN, S.P.M.J., B.S.I. (Muar). ,, Menteri Kerjaraya, DATO' S. SAMY VELLU, s.P.M.J., D.P.M.S., P.C.M., A.M.N. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R.