Safe Child Penarth: Experience with a Safe Community Strategy for Preventing Injuries to Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Airport 2040 Masterplan

Setting intentions for Wales’ National Airport CARDIFF AIRPORT 2040 MASTERPLAN CONTENTS 1 Introduction 6 2 Our Vision, Purpose & Values 8 3 Drivers & Opportunities for Change 10 3.1 Connectivity and accessibility 10 3.2 Customer/passenger experience 10 3.3 Technology 10 3.4 Culture and Identity 12 3.5 Environment and Sustainability 12 3.6 Business and Economy 12 4 Need for a Masterplan 14 5 Cardiff Airport Today 16 5.1 Location and Context 18 5.2 Site Context 20 5.3 Public Transport and Parking 22 5.4 Current Airport Operations 22 5.5 Airside Facilities 26 6 Cardiff Airport Masterplan 2040 28 7 Participation Response 40 8 Next Steps 42 9 Appendices 46 CARDIFF AIRPORT 2040 MASTERPLAN 3 FOREWORD 2018 has been a transformational year for Cardiff Airport and for Wales – we’ve already welcomed over 8% more passengers to the Airport and more inbound visitors to the country than ever before. We’ve delivered on our promise to grow the business, achieving over 50% passenger growth since our change in ownership in 2013. We have also secured a global flagship Middle Eastern carrier in Qatar Airways. This has transformed Cardiff Airport into a vital gateway for both Wales and the UK, which significantly enhances our relationship with the world. We continue to be ambitious and have the aim of achieving 2 million passengers by 2021 and 3 million passengers by 2036. We will continue to substantially improve the Airport for all of our customers, to ensure that anyone who travels in and out of Wales has a truly enjoyable and memorable experience. -

Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone SPG 2019

Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011- 2026 Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance Local Cynllun Development Datblygu December 2019 Plan Lleol Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Cardiff Airport & Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance December 2019 This document is available in other formats upon request e.g. larger font. Please see contact details in Section 9. CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Purpose of the Supplementary Planning Guidance .................................................................... 3 4. Status of the Guidance .............................................................................................................. 3 5. Legislative and Planning Policy Context .................................................................................... 4 5.1. National Legislation ............................................................................................................. 4 5.2. National Policy Context ....................................................................................................... 4 5.3. Local Policy Context ............................................................................................................ 5 5.4. Supplementary Planning -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Near Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT

2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Near Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT 2 Gelli Garn Cottages, St Mary Hill Nr Cowbridge, Vale of Glamorgan, CF35 5DT £450,000 Freehold 3 Bedrooms : 2 Bathrooms : 1 Reception Rooms Hall • Living room • Kitchen-breakfast room • Rear entrance porch • Ground floor shower room Three double bedrooms • Bathroom Generous gardens and grounds of about ¼ of an acre Garage • Driveway parking • Paved patio • Lawns EPC Rating: TBC Directions From Cowbridge proceed in a westerly direction along the A48 and at the first cross roads by the Hamlet of Pentre Meyrick turn right. Continue north along this road, passing Llangan School and carry on further for approximately half a mile turning left after Fferm Goch where indicated to St. Mary Hill. Travel along this lane for about half a mile, bearing left at the next junction. 2 Gelli Garn Cottages will be on your right after a further 300 yards, the first of a pair of semi detached homes. • Cowbridge 0.0 miles • Cardiff City Centre 0.0 miles • M4 (J35) 0.0 miles Your local office: Cowbridge T 01446 773500 E [email protected] Summary of Accommodation ABOUT THE PROPERTY * Traditional semi detached family home * Extended in recent years to create kitchen, ground floor shower room and additional bedroom space. * Large living room with double doors to south-facing front garden * Plenty for room for seating and also for a family sized dining table * Traditional kitchen with room for breakfast table. Electric oven, hob and integrated fridge all to remain * Ground floor shower room * Three double bedrooms and bathroom to the first floor * Principle bedroom with superb views in a southerly direction over farmland GARDENS AND GROUNDS * South facing, paved patio fronting the property accessed via double doors from the living room * Sheltered lawn * Gardens and grounds of close to 1/4 of an acre in total * Block paved, off-road parking for a number of cars * Detached, block built garage (approx. -

A Mysterious Giant Ichthyosaur from the Lowermost Jurassic of Wales

A mysterious giant ichthyosaur from the lowermost Jurassic of Wales JEREMY E. MARTIN, PEGGY VINCENT, GUILLAUME SUAN, TOM SHARPE, PETER HODGES, MATT WILLIAMS, CINDY HOWELLS, and VALENTIN FISCHER Ichthyosaurs rapidly diversified and colonised a wide range vians may challenge our understanding of their evolutionary of ecological niches during the Early and Middle Triassic history. period, but experienced a major decline in diversity near the Here we describe a radius of exceptional size, collected at end of the Triassic. Timing and causes of this demise and the Penarth on the coast of south Wales near Cardiff, UK. This subsequent rapid radiation of the diverse, but less disparate, specimen is comparable in morphology and size to the radius parvipelvian ichthyosaurs are still unknown, notably be- of shastasaurids, and it is likely that it comes from a strati- cause of inadequate sampling in strata of latest Triassic age. graphic horizon considerably younger than the last definite Here, we describe an exceptionally large radius from Lower occurrence of this family, the middle Norian (Motani 2005), Jurassic deposits at Penarth near Cardiff, south Wales (UK) although remains attributable to shastasaurid-like forms from the morphology of which places it within the giant Triassic the Rhaetian of France were mentioned by Bardet et al. (1999) shastasaurids. A tentative total body size estimate, based on and very recently by Fischer et al. (2014). a regression analysis of various complete ichthyosaur skele- Institutional abbreviations.—BRLSI, Bath Royal Literary tons, yields a value of 12–15 m. The specimen is substantially and Scientific Institution, Bath, UK; NHM, Natural History younger than any previously reported last known occur- Museum, London, UK; NMW, National Museum of Wales, rences of shastasaurids and implies a Lazarus range in the Cardiff, UK; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, lowermost Jurassic for this ichthyosaur morphotype. -

Cardiff | Penarth

18 Cardiff | Penarth (St Lukes Avenue) via Cogan, Penarth centre, Stanwell Rd 92 Cardiff | Penarth (St Lukes Avenue) via Bessemer Road, Cogan, Penarth centre, Stanwell Road 92B Cardiff | Penarth | Dinas Powys | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Cogan, Wordsworth Avenue, Murch, Cadoxton 93 Cardiff | Penarth | Sully | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Cogan, Stanwell Road, Cadoxton 94 Cardiff | Penarth | Sully | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Bessemer Road, Cogan, Stanwell Road, Cadoxton 94B on schooldays this bus continues to Colcot (Winston Square) via Barry Civic Office, Gladstone Road, Buttrills Road, Barry Road, Colcot Road and Winston Road school holidays only on school days journey runs direct from Baron’s Court to Merrie Harrier then via Redlands Road to Cefn Mably Lavernock Road continues to Highlight Park as route 98, you can stay on the bus. Mondays to Fridays route number 92 92B 94B 93 92B 94B 92 94 92B 93 92B 94 92 94 92B 93 92 94 92 94 92 city centre Wood Street JQ 0623 0649 0703 0714 0724 0737 0747 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 0857 0907 0917 0926 0936 0946 0956 1006 Bessemer Road x 0657 0712 x 0733 0746 x x 0816 x 0836 x x x 0916 x x x x x x Cogan Leisure Centre 0637 0704 0718 0730 0742 0755 0805 0815 0825 0835 0845 0855 0905 0915 0925 0935 0943 0953 1003 1013 1023 Penarth town centre Windsor Arcade 0641 0710 0724 0736 0748 0801 0811 0821 0831 0841 0849 0901 0911 0921 0931 0941 0949 0959 1009 1019 1029 Penarth Wordsworth Avenue 0740 x 0846 0947 Penarth Cornerswell Road x x x x 0806 x x x x x x x x x x x x x Cefn Mably Lavernock Road -

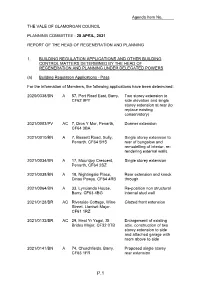

Planning Committee Report 20-04-21

Agenda Item No. THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE : 28 APRIL, 2021 REPORT OF THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING 1. BUILDING REGULATION APPLICATIONS AND OTHER BUILDING CONTROL MATTERS DETERMINED BY THE HEAD OF REGENERATION AND PLANNING UNDER DELEGATED POWERS (a) Building Regulation Applications - Pass For the information of Members, the following applications have been determined: 2020/0338/BN A 57, Port Road East, Barry. Two storey extension to CF62 9PY side elevation and single storey extension at rear (to replace existing conservatory) 2021/0003/PV AC 7, Dros Y Mor, Penarth, Dormer extension CF64 3BA 2021/0010/BN A 7, Bassett Road, Sully, Single storey extension to Penarth. CF64 5HS rear of bungalow and remodelling of interior, re- rendering external walls. 2021/0034/BN A 17, Mountjoy Crescent, Single storey extension Penarth, CF64 2SZ 2021/0038/BN A 18, Nightingale Place, Rear extension and knock Dinas Powys. CF64 4RB through 2021/0064/BN A 33, Lyncianda House, Re-position non structural Barry. CF63 4BG internal stud wall 2021/0128/BR AC Riverside Cottage, Wine Glazed front extension Street, Llantwit Major. CF61 1RZ 2021/0132/BR AC 29, Heol Yr Ysgol, St Enlargement of existing Brides Major, CF32 0TB attic, construction of two storey extension to side and attached garage with room above to side 2021/0141/BN A 74, Churchfields, Barry. Proposed single storey CF63 1FR rear extension P.1 2021/0145/BN A 11, Archer Road, Penarth, Loft conversion and new CF64 3HW fibre slate roof 2021/0146/BN A 30, Heath Avenue, Replace existing beam Penarth. -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Vale of Glamorgan Profile (Final Version at March 2017)

A profile of the Vale of Glamorgan The Vale of Glamorgan is a diverse and beautiful part of Wales. The county is characterised by rolling countryside, coastal communities, busy towns and rural villages but also includes Cardiff Airport, a variety of industry and businesses and Wales’s largest town. The area benefits from good road and rail links and is well placed within the region as an area for employment as a visitor destination and a place to live. The map below shows some key facts about the Vale of Glamorgan. There are however areas of poverty and deprivation and partners are working with local communities to ensure that the needs of different communities are understood and are met, so that all residents can look forward to a bright future. Our population The population of the Vale of Glamorgan as per 2015 mid-year estimates based on 2011 Census data was just under 128,000. Of these, approximately 51% are female and 49% male. The Vale has a similar age profile of population as the Welsh average with 18.5% of the population aged 0-15, 61.1% aged 16-64 and 20.4% aged 65+. Population projections estimate that by 2036 the population aged 0-15 and aged 16-64 will decrease. The Vale also has an ageing population with the number of people aged 65+ predicted to significantly increase and be above the Welsh average. 1 Currently, the percentage of the Vale’s population reporting activity limitations due to a disability is one of the lowest in Wales. -

Model Design Guide for Wales Residential Development

a model design guide for Wales residential development prepared by for PLANNING OFFICERS SOCIETY FOR WALES with the support of WELSH ASSEMBLY GOVERNMENT March 2005 a model design guide 02 for Wales residential development contents 1.0 introduction 2.0 the objectives of good design 3.0 the design process 4.0 submitting the application 5.0 design appraisal 6.0 case studies appendix further reading glossary RAISDALE ROAD: LOYN & CO ARCHITECTS a model design guide 03 for Wales residential development a model design guide 04 for Wales residential development 1.0 introduction 1.1 All design and development contributes to a nation's image and says much about its culture, con- fidence and aspirations. It also directly affects the social, economic and environmental well being of cities, towns and villages. 1.2 The Welsh Assembly Government is committed to achieving good design in all development at every scale throughout Wales. Good design is a key aim of the planning system and Planning Policy Wales [WAG 2002] requires that Unitary Development Plans (UDPs) provide clear policies setting out planning authorities' design expectations. Technical Advice Note 12 (TAN 12) [WAG 2002A] gives advice to local planning authorities on how good design may be facilitated within the plan- ning system. 1.3 This document has been designed as a practical tool to be used by local planning authorities as supplementary planning guidance to meet the requirements of PPW and convey the design impli- cations of TAN 12 to anyone proposing new residential development in excess of 1 dwelling. It is a requirement of PPW and TAN 12 that applications for planning permission are accompanied by a 'design statement'. -

Penarth Barry - Penarth

88 88 Y Barri - Penarth Barry - Penarth DRWY / VIA: Barry Waterfront, Weston Square, Bendrick, Sully, Cosmeston, Penarth Esplanade & Town Centre GWEITHREDWR / OPERATOR: Easyway (Ffôn / Tel: 01656 655655) o ddydd Llun / from 16.04.2018 Llwybr: Route: PENARTH: Windsor Terrace (Town Centre), Beach Rd, Penarth Esplanade (Pier), Bridgeman Rd, Marine Parade, Raisdale Rd, Westbourne Rd, Lavernock Rd, COSMESTON: Lavernock Rd, SULLY: South Rd, Hayes Rd, BENDRICK, Hayes Rd, Sully Moors Rd, Ty Verlon Industrial Estate, Cardiff Rd, CADOXTON: Little Moors Hill, Vere Street, Weston Square, BARRY, Holton Rd (upper), Court Road, Wyndham St, King Square, Holton Rd (lower), Civic Offices (Clinic stop), Gladstone Bridge, BARRY WATERFRONT: Ffordd y Mileniwm, Subway Rd, Dock View Rd (Barry Rail Station), Lower Pike St, Jewel St, then as main route above in reverse from Holton Rd (upper - Tadross Hotel) back to Penarth Town Centre. 88 I Benarth To Penarth 88 DYDD LLUN hyd DDYDD SADWRN MONDAY to SATURDAY Nodiadau / Notes Barry Town Centre (2. Wyndham Street) …. 0655 0755 0855 0955 1055 1155 1355 1455 Civic Offices (Clinic) …. 0657 0757 0857 0957 1057 1157 1357 1457 Morrisons Store (Ffordd y Mileniwm) …. 0700 0800 0900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 Dock View Rd (Barry Dock Rail Station) …. 0702 0802 0902 1002 1102 1302 1402 1502 Bassett (Tadross Hotel, Holton Road) …. 0703 0803 0903 1003 1103 1303 1403 1503 Muslim Centre (Holton Road / Weston Sq.) 0704 0804 0904 1004 1104 1304 1404 1504 Cadoxton (Vere Street) = …. 0705 0805 0905 1005 1105 1305 1405 1505 Ty Verlon Industrial Estate (McDonalds) …. 0707 0807 0907 1007 1107 1307 1407 1507 Bendrick …. -

30A Archer Road, Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan

Chartered Surveyors, Auctioneers and Estate Agents 3 Washington Buildings, Stanwell Road, Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan, CF64 2AD Tel: 02920 712266 Fax: 02920 711134 Email: [email protected] www.wattsandmorgan.co.uk 30a Archer Road , Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan. A totally refurbished ground floor apartment situated in a quiet and popular location within easy walking distance of Town Centre. The property comprises communal entrance hall, entrance hall, living/dining room, kitchen, double-bedroom and bathroom. The property benefits from a small front garden and newly extended lease. No Chain. EPC - D. Guide Price £139,5 00 Leasehold Ref: 18328 Cowbridge Residential Tel: 01446 773500 Agricultural Tel: 01446 774152 Penarth Tel: 029 2071 2266 London Tel: 02074 081400 30a Archer Road , Penarth. SITUATION ENTRANCE HALL Penarth Town is known locally as ‘The garden by Entered via a wooden door, decorative tiled floor, the sea’ and offers a range of good quality shops, voice entry phone, inset ceiling spot lights and a public library, leisure centre and various radiator. sport ing clubs and has managed to preserve its special Victorian character, and remains a seaside LIVING/DINING ROOM 19' 2" x 11' 6" (5.86m x Town of considerable charm and elegance. There 3.52m) are walks along the cliff tops and leisurely walks A large bay window to front, wood effect in Windsor Gardens, the Seafront Park, with views laminated flooring, picture rail, coved ceiling and across the Br istol Channel to the Somerset coast. radiator. “The Vale” as it is often known, offers attractive countryside, a mixture of sandy and stony beaches KITCHEN 6' 9" x 7' 7" (2.06m x 2.33m) along the Heritage Coast Conservation Area and a A newly fitted kitchen with floor and wall units good range of leisure and country pursuits.