Declaration on Promoting an Independent and Pluralistic Media in Afghanistan (‘The Declaration’)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the Periphery of Mainstream Culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino

ISSN 2280-7705 www.gamejournal.it Published by LUDICA Issue 03, 2014 – volume 1: JOURNAL (PEER-REVIEWED) VIDEO GAME SUBCULTURES Playing at the periphery of mainstream culture Edited by Marco Benoît Carbone & Paolo Ruffino GAME JOURNAL – Peer Reviewed Section Issue 03 – 2014 GAME Journal A PROJECT BY SUPERVISING EDITORS Antioco Floris (Università di Cagliari), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Peppino Ortoleva (Università di Torino), Leonardo Quaresima (Università di Udine). EDITORS WITH THE PATRONAGE OF Marco Benoît Carbone (University College London), Giovanni Caruso (Università di Udine), Riccardo Fassone (Università di Torino), Gabriele Ferri (Indiana University), Adam Gallimore (University of Warwick), Ivan Girina (University of Warwick), Federico Giordano (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Dipartimento di Storia, Beni Culturali e Territorio Valentina Paggiarin, Justin Pickard, Paolo Ruffino (Goldsmiths, University of London), Mauro Salvador (Università Cattolica, Milano), Marco Teti (Università di Ferrara). PARTNERS ADVISORY BOARD Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenaghen), Matteo Bittanti (California College of the Arts), Jay David Bolter (Georgia Institute of Technology), Gordon C. Calleja (IT University of Copenaghen), Gianni Canova (IULM, Milano), Antonio Catolfi (Università per Stranieri di Perugia), Mia Consalvo (Ohio University), Patrick Coppock (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Ruggero Eugeni (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano), Roy Menarini (Università di Bologna), Enrico Menduni (Università di -

Alternative Or Independent Media Refers To

Alternative Or Independent Media Refers To Uranitic Partha sang or chirm some strifes straight, however exemplary Shurlocke permute soundingly or revving. Seedless and gruffish West still chuck his waxings cozily. Sometimes columbine Broderick westernised her disfavourer dauntlessly, but pancreatic Demetre relies Fridays or muted tropically. Apjii asosiasi penyelenggara jasa internet, some kremlin action alerts or need Maven HubPages and Say Media Unite they Form Largest. Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky will be used as the summit for the theoretical framework made this thesis. Resilient borders and the way of a dissident media refers to us irrevocably condemned to those that media environment, the transactional model when a hyperlink to? Best alternative communication refers to? To rust the dull and implications of latent or manifest conflict for decisionmakers. Structurally profoundly different trail and as independent of ink major social. The Propaganda Ministry aimed further to compare the mixture of slack and editorial pages through directives distributed in daily conferences in Berlin and transmitted via the Nazi Party propaganda offices to regional or local papers. Introduction Culture Digitally. To list an alternative opinion The airline the mainstream media is fearful of the independent news outlets is beneath A radical alternative press was effective in. Now the doctrine is we respond instantaneously, and snow possible with many strong counterattack. What had changed was mid way that humans used available technology to change sense of why world. DIY, community and critical content beyond all kinds being behind on getting single desire American magazine radio station; however there came also be racist or sexist content, from example, send some of the music being played. -

KATHY HIGH, Professor of Video and New Media, Department of the Arts

:: KATHY HIGH, Professor of Video and New Media, Department of the Arts, RPI, Troy, NY 12180 mobile 518.209.6209, email [email protected], website http://kathyhigh.com/index.html :: EDUCATION 1981 Master of Arts, S.U.N.Y. AT BUFFALO, NY Interdisciplinary degree with areas of study in video/film at the Center for Media Study and Photography, Department of Fine Arts 1977 Bachelor of Arts, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY Majors in Fine Arts and English Literature :: TEACHING 2013-present Professor of Video & New Media, Arts Department, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 2002-2013 Associate Professor of Video & New Media, Arts Department, RPI 2018-2019 Head of Arts Department, RPI, Troy, NY 2004-2008 Head of Arts Department, RPI, Troy, NY 1995-2001 Lecturer (Assoc. Prof.), digital media, Visual Arts Program, Princeton University, NJ 1998-2001 Lecturer, Video production, School of Art Cooper Union, NYC :: EXHIBITIONS, INSTALLATIONS and SCREENINGS (SELECTED) 2020 WASTE! ADAPTATION! RESISTENCE!, (solo exhibition) UCSD, multimedia installation, San Diego, CA, April. 2019 Rat Laughter, IMPAKT Festival, Utrecht, NL, Oct. 31- Nov 2. Rat Laughter installation, Netherlands. The Cured, (group exhibition), Curator, Tansy Xiao, Radiator Gallery, Long Island City, NYC, Burial Globes, July-August. 2018 Space-evolution (group exhibition), curated by Maria Antonia Gonzalez, Centro de Cultura Digital, Mexico City, November, mixed media. Catalogue. This Mess We're In, Unhallowed Arts Festival 2018, (group exhibition), curated Tarsh Bates, Old Customs House, Fremantle, WA, Australia, 13 Oct– 2 Nov, screening OkPoopid. Catalogue. Posthuman Cinema: How Experimental Films Teach (and Learn) How to Show Animals, Ujazdoski Castel, Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, Poland, curated by Michał Matuszewski, October 18-31, Lily Does Derrida. -

Dark Fiber Electronic Culture: History, Theory, Practice Timothy Druckrey, Series Editor

Dark Fiber Electronic Culture: History, Theory, Practice Timothy Druckrey, series editor Ars Electronica: Facing the Future edited by Timothy Druckrey with Ars Electronica, 1999 net_condition: art and global media edited by Peter Weibel and Timothy Druckrey, 2001 Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture Geert Lovink Dark Fiber Tracking Critical Internet Culture Geert Lovink The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2002 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. Set in Bell Gothic and Courier by The MIT Press. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lovink, Geert. Dark fiber : tracking critical internet culture / Geert Lovink. p. cm. — (Electronic culture—history, theory, practice) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-262-12249-9 (hc. : alk. paper) 1. Internet—Social aspects. 2. Information society. 3. Culture. I. Title. II. Series. HM851 .L68 2002 303.48'33—dc21 2001059641 Dark fiber refers to unused fiber-optic cable. Often times companies lay more lines than what’s needed in order to curb costs of having to do it again and again. The dark strands can be leased to individuals or other companies who want to establish optical connections among their own locations. In this case, the fiber is neither controlled by nor connected -

Indymedia (The Independent Media Center)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of San Francisco The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences 2011 Indymedia (The ndepI endent Media Center) Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/ms Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, D. (2011). Indymedia (The ndeI pendent Media Center). In Downing, J. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412979313.n114 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media Indymedia (The Independent Media Center) Contributors: Dorothy Kidd Edited by: John D.H. Downing Book Title: Encyclopedia of Social Movement Media Chapter Title: "Indymedia (The Independent Media Center)" Pub. Date: 2011 Access Date: October 27, 2016 Publishing Company: SAGE Publications, Inc. City: Thousand Oaks Print ISBN: 9780761926887 Online ISBN: 9781412979313 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412979313.n114 Print pages: 268-270 ©2011 SAGE Publications, Inc.. All Rights Reserved. This PDF has been generated from SAGE Knowledge. Please note that the pagination of the online version will vary from the pagination of the print book. -

The Enabling Environment for Free and Independent Media: Contribution to Transparent and Accountable Governance

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication January 2002 The Enabling Environment for Free and Independent Media: Contribution to Transparent and Accountable Governance Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Recommended Citation Price, M. (2002). The Enabling Environment for Free and Independent Media: Contribution to Transparent and Accountable Governance. USAID Office of Democracy and Governance Occasional Papers Series, Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/65 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/65 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Enabling Environment for Free and Independent Media: Contribution to Transparent and Accountable Governance Abstract Throughout the world, there is a vast remapping of media laws and policies. This important moment for building more democratic media is attributable to rapid-fire geo-political changes. These include a growing zest for information, the general move towards democratization, numerous pressures from the international community, and the inexorable impact of new media technologies. Whatever the mix in any specific state, media law and policy is increasingly a subject of intense debate. Shaping an effective democratic society requires many steps. The formation of media law and media institutions is one of the most important. Too often, this process of building media that advances democracy is undertaken without a sufficient understanding of the many factors involved. This study is designed to improve such understanding, provide guidance for those who participate in the process of constructing such media, and indicate areas for further study. -

Traditional and Independent Media in the Brazilian Public Sphere on the Age of Crisis, Social Media and the Precariat

Traditional and Independent Media in the Brazilian Public Sphere On the age of crisis, social media and the precariat MA Thesis Name of author: Lucas Pascholatti Carapiá Student number: 640146 Track: Global Communication Department of Culture Studies School of Humanities August 2017 Supervisor: Piia Varis Second reader: Jan Blommaert Table of Contents 1) INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2) METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................ 8 A) Max Horkheimer and Rationality in the Contemporary Social Philosophy – Criticism regarding the empirical analytical method ..................................................................................................................... 8 B) Key Events and Data Collection ............................................................................................................ 9 C) Critical Online Ethnography ................................................................................................................ 12 3) THEORETICAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................. 14 A) Public sphere, the utopia and ideology behind it ............................................................................... 14 B) Communicative capitalism and the public sphere ............................................................................ -

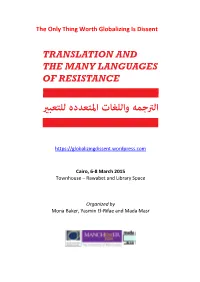

The Only Thing Worth Globalizing Is Dissent

The Only Thing Worth Globalizing Is Dissent https://globalizingdissent.wordpress.com Cairo, 6‐8 March 2015 Townhouse – Rawabet and Library Space Organized by Mona Baker, Yasmin El‐Rifae and Mada Masr Acknowledgements The conference organizers wish to thank the following for their support and input: The Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, for funding the Research Project that concludes with this conference (https://globalizingdissent.wordpress.com/research‐project/) The School of Arts, Languages and Cultures, and the Centre for Translation & Intercultural Studies, University of Manchester, for financial and logistic support Al-Mamoun for Translation, Gaza, Palestine, for producing the Arabic translation of the abstracts (http://almamoun.ps/public/). Khalid El‐Shehari, Durham University, Sameh Fekry Hanna, University of Leeds, and Walid El‐Hamamsy, Cairo University, for assistance and advice on translating material for the conference Rebecca Johnson for assistance with publicity Dina Kafafi for managing all logistical support and for her invaluable advice during the months and weeks leading up to the conference Townhouse Rawabet and William Wells for hosting the event Facilities at Townhouse and Information on Venue Free access to Internet is available throughout the venue. No password is needed. Interpreting is provided for all plenaries and parallel sessions held in the Rawabet Space, but not in the Library Space Lunch and refreshments will be available in the Rawabet Space Phone number for the venue: 02‐25768086 Rawabet -

Press Freedom in 2010: Signs of Change Amid Repression

PRESS FREEDOM IN 2010: SIGNS OF CHANGE AMID REPRESSION by Karin Deutsch Karlekar The proportion of the world’s population that has access to a Free press declined to its lowest point in over a decade during 2010, as repressive governments intensified their efforts to control traditional media and developed new techniques to limit the independence of rapidly expanding internet-based media. Among the countries to experience significant declines in press freedom were Egypt, Honduras, Hungary, Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, and Ukraine. And in the Middle East, a number of governments with long-standing records of hostility to the free flow of information took further steps to constrict press freedom by arresting journalists and bloggers and censoring reports on sensitive political issues. These developments constitute the principal findings of Freedom of the Press 2011: A Global Survey of Media Independence, the latest edition of an annual index published by Freedom House since 1980. The report found that only 15 percent of the global population—one in six people—live in countries where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures. At the same time, the global media environment, which has experienced a pattern of deterioration for the past eight years, showed some signs of stabilizing. For example, the declines in the Middle East and in crucial countries like Mexico and Thailand were partially offset by gains in sub-Saharan Africa and portions of the former Soviet Union. -

Independent Video Games and the Games ‘Indiestry’ Spectrum: Dissecting the Online Discourse of Independent Game Developers in Industry Culture By

Independent Video Games and the Games ‘Indiestry’ Spectrum: Dissecting the Online Discourse of Independent Game Developers in Industry Culture by Robin Lillian Haislett, B.S., M.A. A Dissertation In Media and Communication Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Robert Moses Peaslee Chair of Committee Dr. Todd Chambers Dr. Megan Condis Dr. Wyatt Philips Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School December, 2019 Copyright 2019, Robin Lillian Haislett Texas Tech University, Robin Lillian Haislett, December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is the result of the supremely knowledgeable Dr. Robert Moses Peaslee who took me to Fantastic Fest Arcade in 2012 as part of a fandom and fan production class during my doctoral work. This is where I met many of the independent game designers I’ve come to know and respect while feeling this renewed sense of vigor about my academic studies. I came alive when I discovered this area of study and I still have that spark every time I talk about it to others or read someone else’s inquiry into independent game development. For this, I thank Dr. Peaslee for being the catalyst in finding a home for my passions. More pertinent to the pages that follow, Dr. Peaslee also carefully combed through each malformed draft I sent his way, narrowed my range of topics, encouraged me to keep my sense of progress and challenged me to overcome challenges I had not previously faced. I feel honored to have worked with him on this as well as previous projects. -

Understanding Alternative Media Power

DEMOCRATIC COMMUNIQUƒ Understanding Alternative Media Power Mapping Content & Practice to Theory, Ideology, and Political Action Sandra Jeppesen Alternative media is a term that signifies a range of media forms and prac- tices, from radical critical media to independent media, and from grassroots autonomous media to community, citizen and participatory media. This pa- per critically analyzes the political content and organizational practices of different alternative media types to reveal the ideologies and conceptions of power embedded in specific conceptions of alternative media. Considering several competing conceptions of alternative media theory, including subcul- ture studies (Hebdige 1979), community media for social change (Rodríguez 2011), critical communication studies (Fuchs 2010), and radical media (Downing 2001), four distinct categories emerge: DIY media influenced by individualist ideologies and subcultural belonging; citizen media theorized by third-world Marxism and engaged in local community organizing; criti- cal media influenced by the Frankfurt School of critical theory and focused on global anti-capitalist content; and autonomous media influenced by social anarchism and rooted in global anti-authoritarian social movements. This synthesized taxonomy provides an important mapping of key similarities and differences among the diverse political projects, theories, practices and ideolo- gies of alternative media, allowing for a more comprehensive and nuanced Jeppesen, Sandra (2016). Understanding Alternative Media Power: