March 15, 2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21St Century

An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. Robison Margaret Weigel Building the new field of digital media and learning The MacArthur Foundation launched its five-year, $50 million digital media and learning initiative in 2006 to help determine how digital technologies are changing the way young people learn, play, socialize, and participate in civic life.Answers are critical to developing educational and other social institutions that can meet the needs of this and future generations. The initiative is both marshaling what it is already known about the field and seeding innovation for continued growth. For more information, visit www.digitallearning.macfound.org.To engage in conversations about these projects and the field of digital learning, visit the Spotlight blog at spotlight.macfound.org. About the MacArthur Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private, independent grantmaking institution dedicated to helping groups and individuals foster lasting improvement in the human condition.With assets of $5.5 billion, the Foundation makes grants totaling approximately $200 million annually. For more information or to sign up for MacArthur’s monthly electronic newsletter, visit www.macfound.org. The MacArthur Foundation 140 South Dearborn Street, Suite 1200 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Tel.(312) 726-8000 www.digitallearning.macfound.org An occasional paper on digital media and learning Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century Henry Jenkins, Director of the Comparative Media Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with Katie Clinton Ravi Purushotma Alice J. -

Openness in the Music Business– How Record Labels and Artists May Profit from Reducing Control

Table of Contents TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Dr. Theo Schöller-Stiftungslehrstuhl für Technologie- und Innovationsmanagement Openness in the music business– How record labels and artists may profit from reducing control Johannes L. Wechsler Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften (Dr. rer. pol.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. I. Welpe Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. J. Henkel 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. F. v. Wangenheim Die Dissertation wurde am 09.12.2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften am 11.05.2011 angenommen. i Table of Contents Table of Contents DETAILED TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... II LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................. V LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. VII LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................................IX ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................................................XI 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... -

On-Site Historical Reenactment As Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation

Fall2002 107 Recreation and Re-Creation: On-Site Historical Reenactment as Historiographic Operation at Plimoth Plantation Scott Magelssen Plimoth Plantation, a Massachusetts living history museum depicting the year 1627 in Plymouth Colony, advertises itself as a place where "history comes alive." The site uses costumed Pilgrims, who speak to visitors in a first-person presentvoice, in order to create a total living environment. Reenactment practices like this offer possibilities to teach history in a dynamic manner by immersing visitors in a space that allows them to suspend disbelief and encounter museum exhibits on an affective level. However, whether or not history actually "comes alive"at Plimoth Plantation needs to be addressed, especially in the face of new or postmodem historiography. No longer is it so simple to say the past can "come alive," given that in the last thirty years it has been shown that the "past" is contestable. A case in point, I argue, is the portrayal of Wampanoag Natives at Plimoth Plantation's "Hobbamock's Homesite." Here, the Native Wampanoag Interpretation Program refuses tojoin their Pilgrim counterparts in using first person interpretation, choosing instead to address visitors in their own voices. For the Native Interpreters, speaking in seventeenth-century voices would disallow presentationoftheir own accounts ofthe way colonists treated native peoples after 1627. Yet, from what I have learned in recent interviews with Plimoth's Public Relations Department, plans are underway to address the disparity in interpretive modes between the Pilgrim Village and Hobbamock's Homesite by introducing first person programming in the latter. I Coming from a theatre history and theory background, and looking back on three years of research at Plimoth and other living history museums, I would like to trouble this attempt to smooth over the differences between the two sites. -

Historical Reenactment in Photography: Familiarizing with the Otherness of the Past?

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND FOLKLORE STUDIES WITH ETHNOGRAPHIC MUSEUM AT THE BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Multi-Mediatized Other The Construction of Reality in East-Central Europe, 1945–1980 EDITED BY DAGNOSŁAW DEMSKI ANELIA KASSABOVA ILDIKÓ SZ. KRISTÓF LIISI LAINESTE KAMILA BARANIECKA-OLSZEWSKA BUDAPEST 2017 Contents 9 Acknowledgements 11 Dagnosław Demski in cooperation with Anelia Kassabova, Ildikó Sz. Kristóf, Liisi Laineste and Kamila Baraniecka-Olszewska Within and Across the Media Borders 1. Mediating Reality: Reflections and Images 30 Dagnosław Demski Cultural Production of the Real Through Picturing Difference in the Polish Media: 1940s–1960s 64 Zbigniew Libera, Magdalena Sztandara Ethnographers’ Self-Depiction in the Photographs from the Field. The Example of Post-War Ethnology in Poland 94 Valentina Vaseva The Other Dead—the Image of the “Immortal” Communist Leaders in Media Propaganda 104 Ilkim Buke-Okyar The Arab Other in Turkish Political Cartoons, 1908–1939 2. Transmediality and Intermediality 128 Ildikó Sz. Kristóf (Multi-)Mediatized Indians in Socialist Hungary: Winnetou, Tokei-ihto, and Other Popular Heroes of the 1970s in East-Central Europe 156 Tomislav Oroz The Historical Other as a Contemporary Figure of Socialism—Renegotiating Images of the Past in Yugoslavia Through the Figure of Matija Gubec 178 Annemarie Sorescu-Marinković Multimedial Perception and Discursive Representation of the Others: Yugoslav Television in Communist Romania 198 Katya Lachowicz The Cultivation of Image in the Multimedial Landscape of the Polish Film Chronicle 214 Dominika Czarnecka Otherness in Representations of Polish Beauty Queens: From Miss Baltic Coast Pageants to Miss Polonia Contests in the 1950s 3. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

November 2008

>> TOP DECK The Industry's Most Influential Players NOVEMBER 2008 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >> BUILDING TOOLS >> PRODUCT REVIEW >> LITTLE TOUCHES GOOD DESIGN FOR NVIDIA'S PERFHUD 6 ARTISTIC FLOURISHES INTERNAL SYSTEMS THAT SELL THE ILLUSION CERTAIN AFFINITY'S AGEOFBOOTY 00811gd_cover_vIjf.indd811gd_cover_vIjf.indd 1 110/21/080/21/08 77:01:43:01:43 PPMM “ReplayDIRECTOR rocks. I doubt we'd have found it otherwise. It turned out to be an occasional array overwrite that would cause random memory corruption…” Meilin Wong, Developer, Crystal Dynamics BUGS. PETRIFIED. RECORD. REPLAY. FIXED. ReplayDIRECTOR™ gives you Deep Recording. This is much more than just video capture. Replay records every line of code that you execute and makes certain that it will Replay with the same path of execution through your code. Every time. Instantly Replay any bug you can find. Seriously. DEEP RECORDING. NO SOURCE MODS. download today at www.replaysolutions.com email us at [email protected] REPLAY SOLUTIONS 1600 Seaport Blvd., Suite 310, Redwood City, CA, 94063 - Tel: 650-472-2208 Fax: 650-240-0403 accelerating you to market ©Replay Solutions, LLC. All rights reserved. Product features, specifications, system requirements and availability are subject to change without notice. ReplayDIRECTOR and the Replay Solutions logo are registered trademarks of Replay Solutions, LLC in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks contained herein are the property of their respective owners. []CONTENTS NOVEMBER 2008 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 10 FEATURES 7 GAME DEVELOPER'S TOP DECK Not all game developers are cards, but many of them are unique in their way—in Game Developer's first Top Deck feature, we name the top creatives, money makers, and innovators, highlighting both individual and company achievements. -

Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: an Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri, St. Louis University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 11-22-2005 Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Holt, Thomas Jeffrey, "Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers" (2005). Dissertations. 616. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/616 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers by THOMAS J. HOLT M.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2003 B.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2000 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI- ST. LOUIS In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Criminology and Criminal Justice August, 2005 Advisory Committee Jody Miller, Ph. D. Chairperson Scott H. Decker, Ph. D. G. David Curry, Ph. D. Vicki Sauter, Ph. D. Copyright 2005 by Thomas Jeffrey Holt All Rights Reserved Holt, Thomas, 2005, UMSL, p. -

Kristián Néky (FAV, Bakalárské Prezenčné Štúdium)

Masarykova univerzita Filosofická fakulta Ústav filmu a audiovizuální kultury Kristián Néky (FAV, bakalárské prezenčné štúdium) Stratégie spoločnosti Rooster Teeth v oblasti online video tvorby v rokoch 2003–2019 Bakalárska diplomová práca Vedúci práce: Mgr. Michal Večeřa, Ph.D. Brno 2019 Prehlasujem, že som pracoval samostatne a použil iba tu uvedené zdroje. V Brne dňa 20. 6. 2019 ......................................................... Kristián Néky Ďakujem Mgr. Michalovi Večeřovi, Ph.D. za všetky pripomienky, rady a trpezlivosť, ktoré mi venoval pri vedení tejto bakalárskej práce. Rád by som zároveň poďakoval svojej rodine a najbližším priateľom, ktorí mi boli vždy silnou oporou. OBSAH 1 ÚVOD ............................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 PROBLEMATIKA ZDROJOV ...................................................................................................... 6 2 MACHINIMA AKO FOLKLÓRNA ANIMÁCIA NA PRELOME STOROČÍ .............................................. 8 2.1 POČIATKY FENOMÉNU MACHINIMA ...................................................................................... 8 2.2 QUAKE A CESTA KINEMATOGRAFIE VIRTUÁLNYCH PRIESTOROV KU ŠIROKÉMU INTERNETOVÉMU PUBLIKU............................................................................................................... 11 2.3 PÔVODNÁ DEMOSCÉNA ....................................................................................................... 16 2.4 POPULARIZÁCIA KINEMATOGRAFIE -

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin

Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Volume 6, No. 6: October, 1996 Southern Fandom Confederation Contents Ad Rates The Carpetbagger..................................................................... 1 Type Full-Page Half-Page 1/4 Page Another Con Report................................................................4 Fan $25.00 $12.50 $7.25 Treasurer's Report................................................................... 5 Mad Dog's Southern Convention Listing............................. 6 Pro $50.00 $25.00 $12.50 Southern Fanzines................................................................... 8 Southern Fandom on the Web................................................9 Addresses Southern Clubs...................................................................... 10 Letters..................................................................................... 13 Physical Mail: SFC/DSC By-laws...................................................... 20 President Tom Feller, Box 13626,Jackson, MS 39236-3626 Cover Artist........................................................John Martello Vice-President Bill Francis, P.O. Box 1271, Policies Brunswick, GA 31521 The Southern Fandom Confederation Bulletin Secretary-Treasurer Judy Bemis, 1405 (SFCB) Vol. 6, No. 6, October, 1996, is the official Waterwinds CT,Wake Forest, NC 27587 publication of the Southern Fandom Confederation (SFC), a not-for-profit literary organization and J. R. Madden, 7515 Shermgham Avenue, Baton information clearinghouse dedicated to the service of Rouge, LA 70808-5762 -

The Song Remains … the Same? Three Case Studies of Issues of Digital Preservation in Second Life Performance Practices

The Song Remains … The Same? Three Case Studies of Issues of Digital Preservation in Second Life Performance Practices Dennis Moser I. Conceptual Differences Across Disciplines: Needs & Approaches The practice of documentation of performances such as music, theater, and dance and performance art is an integral part of the cultural record. As such, it is subject to change and evolution over time, as well as the vagaries of natural catastrophe, social disorder, or any of the myriad disrupters of human history. The application of the practice of documentation varies according to the discipline utilizing it; indeed, even its efficacy varies from culture to culture and from discipline to discipline. Couple this with our movement deeper and deeper into the use of digital technology for the manifestation of culture and we must grapple with new solutions for capturing and conveying the essentials of these acts of expression. The emergence of performance and installation art in the 20th century gave rise to a field of critical theory somewhat at odds with other approaches of documentation, couched as it was in the visual arts. While aspects of theater and dance have influenced this critical theory, the performance practice considerations of music have not played as much a role in defining it. Indeed, considerable discussion has been generated, over understanding just what comprises “documentation”, whether photography is ‘documentary’ or ‘theatrical’, or if it is a ‘conceptual medium for documentation’ (Taylor, 2009). This reflects a concern for the “visual” aspect of “performance” art as opposed to the temporal aspects so inherent in both music and dance. -

Lucasarts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games

LucasArts and the Design of Successful Adventure Games: The True Secret of Monkey Island by Cameron Warren 5056794 for STS 145 Winter 2003 March 18, 2003 2 The history of computer adventure gaming is a long one, dating back to the first visits of Will Crowther to the Mammoth Caves back in the 1960s and 1970s (Jerz). How then did a wannabe pirate with a preposterous name manage to hijack the original computer game genre, starring in some of the most memorable adventures ever to grace the personal computer? Is it the yearning of game players to participate in swashbuckling adventures? The allure of life as a pirate? A craving to be on the high seas? Strangely enough, the Monkey Island series of games by LucasArts satisfies none of these desires; it manages to keep the attention of gamers through an admirable mix of humorous dialogue and inventive puzzles. The strength of this formula has allowed the Monkey Island series, along with the other varied adventure game offerings from LucasArts, to remain a viable alternative in a computer game marketplace increasingly filled with big- budget first-person shooters and real-time strategy games. Indeed, the LucasArts adventure games are the last stronghold of adventure gaming in America. What has allowed LucasArts to create games that continue to be successful in a genre that has floundered so much in recent years? The solution to this problem is found through examining the history of Monkey Island. LucasArts’ secret to success is the combination of tradition and evolution. With each successive title, Monkey Island has made significant strides in technology, while at the same time staying true to a basic gameplay formula. -

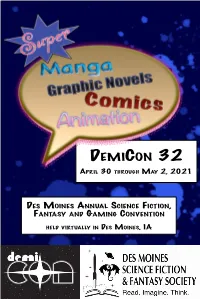

Demicon 32 Program Book

DEMICON 32 APRIL 30 THROUGH MAY 2, 2021 DES MOINES ANNUAL SCIENCE FICTION, FANTASY AND GAMING CONVENTION HELD VIRTUALLY IN DES MOINES, IA CONTENTS Welcome - 4 Department Heads/DMSFFS - 5 Virtual World of DemiCon - 6 Convention Rules - 8 Guests Guests of Honor/Toastmasters - 10 Professional Guests/ Memorial - 12 Hall of Fame - 14 Artwork - 15 Donate/Charity Auction - 16 Venues - 17 Shopping Venues - 18 Programming - 19 Areas of Interest Contests - 20 DemiCon Channel - 22 Gaming - 23 Programming Schedule - 24 Thank You - 27 The After: DemiCon 2022 - 28 CONCOM THE DES MOINES SCIENCE FICTION & “ALL OUR DREAMS CAN COME TRUE, IF WE HAVE THE COURAGE TO FANTASY SOCIETY,INC. (DMSFFS)IS THE CONCOM: JOE STRUSS,SALLIE ABBA,JESSICA GUILE, PURSUE THEM.” – WALT DISNEY LOCAL 501(C)(3) CHARITY NON-PROFIT JUDY ZAJEC,NATE FARMER ORGANIZATION THAT SPONSORS DEMICON. ANIMÉ: SAM SAM HACKETT YES, AND WELCOME TO DEMICON 32: SUPER MANGA GRAPHIC THIS VOLUNTEER RUN ORGANIZATION STANDS ARCHIVIST: SALLIE ABBA NOVELS COMICS ANIMATION! BY THE ORGANIZATIONʻS MISSION ART SHOW: MICHAEL OATMAN MAKE SURE YOU MEET OUR ARTIST GUESTS OF HONOR AND DRAGON SALLIE ABBA STATEMENT: TO INSPIRE INDIVIDUALS AND BLOOD DRIVE: SHERIL BOGENRIEF AFICIONADOS DAVID LEE PANCAKE AND ALISON JOHNSTUN.OUR COMMUNITIES TO READ,IMAGINE AND LORD OF DRINK: KRIS MCBRIDE AUTHOR GUEST OF HONOR IS THE INCREDIBLE LETTIE PRELL. HER WORK THINK; CREATING A BETTER WORLD CHANNEL MASTER: JOE STRUSS EXPLORES THE EDGE WHERE HUMANS AND THEIR TECHNOLOGY ARE THROUGH EDUCATION AND SUPPORT OF CONSUITE: MANDI ARTHUR-STRUSS,MONICA OATMAN, INCREASINGLY MERGING. LITERACY, SCIENCE, AND THE ARTS.DEMICON WIL WARNER SUSAN LEABHART AND MITCH THOMPSON ARE OUR WONDERFUL IS ONE OF MANY EVENTS THAT DMSFFS CONTESTS: SALLIE ABBA TOASTMASTERS.SUE IS OFTEN FOUND REGALING ON MANY DIVERSE AND HOSTS HE REST OF THE YEAR IS FILLED WITH .T DATABASE: CRAIG LEABHART INTERESTING TOPICS (LIKE TIME TRAVELING).