Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: an Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A the Hacker

A The Hacker Madame Curie once said “En science, nous devons nous int´eresser aux choses, non aux personnes [In science, we should be interested in things, not in people].” Things, however, have since changed, and today we have to be interested not just in the facts of computer security and crime, but in the people who perpetrate these acts. Hence this discussion of hackers. Over the centuries, the term “hacker” has referred to various activities. We are familiar with usages such as “a carpenter hacking wood with an ax” and “a butcher hacking meat with a cleaver,” but it seems that the modern, computer-related form of this term originated in the many pranks and practi- cal jokes perpetrated by students at MIT in the 1960s. As an example of the many meanings assigned to this term, see [Schneier 04] which, among much other information, explains why Galileo was a hacker but Aristotle wasn’t. A hack is a person lacking talent or ability, as in a “hack writer.” Hack as a verb is used in contexts such as “hack the media,” “hack your brain,” and “hack your reputation.” Recently, it has also come to mean either a kludge, or the opposite of a kludge, as in a clever or elegant solution to a difficult problem. A hack also means a simple but often inelegant solution or technique. The following tentative definitions are quoted from the jargon file ([jargon 04], edited by Eric S. Raymond): 1. A person who enjoys exploring the details of programmable systems and how to stretch their capabilities, as opposed to most users, who prefer to learn only the minimum necessary. -

Hackers Wanted : an Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market / Martin C

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. H4CKER5 WANTED An Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market MARTIN C. LIBICKI DAVID SENTY C O R P O R A T I O N JULIA POLLAK NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION H4CKER5 WANTED An Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market MARTIN C. -

The Brain in a Vat in Cyberpunk: the Persistence of the Flesh

Stud. Hist. Phil. Biol. & Biomed. Sci. 35 (2004) 287–305 www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc The brain in a vat in cyberpunk: the persistence of the flesh Dani Cavallaro 1 Waterside Place, London NW1 8JT, UK Abstract This essay argues that the image of the brain in a vat metaphorically encapsulates articu- lations of the relationship between the corporeal and the technological dimensions found in cyberpunk fiction and cinema. Cyberpunk is concurrently concerned with actual and imaginary metamorphoses of biological organisms into machines, and of mechanical appara- tuses into living entities. Its recurring representation of human beings hooked up to digital matrices vividly recalls the envatted brain activated by electric stimuli, which Hilary Putnam has theorized in the context of contemporary epistemology. At the same time, cyberpunk imaginatively raises the same epistemological questions instigated by Putnam. These concern the cognitive processes associated with the collusion of human and mechanical creatures, and related metaphysical and ethical issues spawned by such processes. As a philosophical trope, the brain in a vat would appear to pivot on the notion of a disembodied subject consisting of sheer mentation. However, literary and cinematic interpretations of the image in cyberpunk persistently foreground the obdurate materiality of the flesh—often in its most grisly and grotesque incarnations. # 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Brains in vats; Materiality; Disembodiment; Cyborgs; Cyberpunk What is here proposed is that the brain in a vat image, an important trope in contemporary epistemology, is also an intriguing metaphor for one of cyberpunk’s pivotal preoccupations: namely, the relationship between the body and technology. -

Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of the Worlds by Steven Levy 08.18.08

Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of t... http://www.wired.com/print/culture/art/magazine/16-09/mf_ste... << Back to Article WIRED MAGAZINE: 16.09 Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of the Worlds By Steven Levy 08.18.08 Illustration: Nate Van Dyke Tonight's subject at the History Book Club: the Vikings. This is primo stuff for the men who gather once a month in Seattle to gab about some long-gone era or icon, from early Romans to Frederick the Great. You really can't beat tales of merciless Scandinavian pirate forays and bloody ninth-century clashes. To complement the evening's topic, one clubber is bringing mead. The dinner, of course, is meat cooked over fire. "Damp will be the weather, yet hot the pyre in my backyard," read the email invite, written by host Njall Mildew-Beard. That's Neal Stephenson, best-selling novelist, cult science fictionist, and literary channeler of the hacker mindset. For Stephenson, whose books mash up past, present, and future—and whose hotly awaited new work imagines an entire planet, with 7,000 years of its own history—the HBC is a way to mix background reading and socializing. "Neal was already doing the research," says computer graphics pioneer Alvy Ray Smith, who used to host the club until he moved from a house to a less convenient downtown apartment. "So why not read the books and talk about them, too?" With his shaved head and (mildewless) beard, Stephenson could cut something of an imposing figure. -

Ethical Hacking

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 6, June 2015 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Ethical Hacking Susidharthaka Satapathy , Dr.Rasmi Ranjan Patra CSA, CPGS, OUAT, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India Abstract- In today's world where the information damaged the target system nor steal the information, they communication technique has brought the world together there is evaluate target system security and report back to the owner one of the increase growing areas is security of network ,which about the threats found. certainly generate discussion of ETHICAL HACKING . The main reason behind the discussion of ethical hacking is insecurity of the network i.e. hacking. The need of ethical hacking is to IV. FATHER OF HACKING protect the system from the damage caused by the hackers. The In 1971, John Draper , aka captain crunch, was one of the main reason behind the study of ethical hacking is to evaluate best known early phone hacker & one of the few who can be target system security & report back to owner. This paper helps called one of the father's of hacking. to generate a brief idea of ethical hacking & all its aspects. Index Terms- Hacker, security, firewall, automated, hacked, V. IS HACKING NECESSARY crackers Hacking is not what we think , It is an art of exploring the threats in a system . Today it sounds something with negative I. INTRODUCTION shade , but it is not exactly that many professionals hack system so as to learn the deficiencies in them and to overcome from it he increasingly growth of internet has given an entrance and try to improve the system security. -

Address Munging: the Practice of Disguising, Or Munging, an E-Mail Address to Prevent It Being Automatically Collected and Used

Address Munging: the practice of disguising, or munging, an e-mail address to prevent it being automatically collected and used as a target for people and organizations that send unsolicited bulk e-mail address. Adware: or advertising-supported software is any software package which automatically plays, displays, or downloads advertising material to a computer after the software is installed on it or while the application is being used. Some types of adware are also spyware and can be classified as privacy-invasive software. Adware is software designed to force pre-chosen ads to display on your system. Some adware is designed to be malicious and will pop up ads with such speed and frequency that they seem to be taking over everything, slowing down your system and tying up all of your system resources. When adware is coupled with spyware, it can be a frustrating ride, to say the least. Backdoor: in a computer system (or cryptosystem or algorithm) is a method of bypassing normal authentication, securing remote access to a computer, obtaining access to plaintext, and so on, while attempting to remain undetected. The backdoor may take the form of an installed program (e.g., Back Orifice), or could be a modification to an existing program or hardware device. A back door is a point of entry that circumvents normal security and can be used by a cracker to access a network or computer system. Usually back doors are created by system developers as shortcuts to speed access through security during the development stage and then are overlooked and never properly removed during final implementation. -

Paradise Lost , Book III, Line 18

_Paradise Lost_, book III, line 18 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ++++++++++Hacker's Encyclopedia++++++++ ===========by Logik Bomb (FOA)======== <http://www.xmission.com/~ryder/hack.html> ---------------(1997- Revised Second Edition)-------- ##################V2.5################## %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% "[W]atch where you go once you have entered here, and to whom you turn! Do not be misled by that wide and easy passage!" And my Guide [said] to him: "That is not your concern; it is his fate to enter every door. This has been willed where what is willed must be, and is not yours to question. Say no more." -Dante Alighieri _The Inferno_, 1321 Translated by John Ciardi Acknowledgments ---------------------------- Dedicated to all those who disseminate information, forbidden or otherwise. Also, I should note that a few of these entries are taken from "A Complete List of Hacker Slang and Other Things," Version 1C, by Casual, Bloodwing and Crusader; this doc started out as an unofficial update. However, I've updated, altered, expanded, re-written and otherwise torn apart the original document, so I'd be surprised if you could find any vestiges of the original file left. I think the list is very informative; it came out in 1990, though, which makes it somewhat outdated. I also got a lot of information from the works listed in my bibliography, (it's at the end, after all the quotes) as well as many miscellaneous back issues of such e-zines as _Cheap Truth _, _40Hex_, the _LOD/H Technical Journals_ and _Phrack Magazine_; and print magazines such as _Internet Underground_, _Macworld_, _Mondo 2000_, _Newsweek_, _2600: The Hacker Quarterly_, _U.S. News & World Report_, _Time_, and _Wired_; in addition to various people I've consulted. -

Tangled Web : Tales of Digital Crime from the Shadows of Cyberspace

TANGLED WEB Tales of Digital Crime from the Shadows of Cyberspace RICHARD POWER A Division of Macmillan USA 201 West 103rd Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46290 Tangled Web: Tales of Digital Crime Associate Publisher from the Shadows of Cyberspace Tracy Dunkelberger Copyright 2000 by Que Corporation Acquisitions Editor All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a Kathryn Purdum retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, pho- Development Editor tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Hugh Vandivier publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the infor- mation contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken in the Managing Editor preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility Thomas Hayes for errors or omissions. Nor is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. Project Editor International Standard Book Number: 0-7897-2443-x Tonya Simpson Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-106209 Copy Editor Printed in the United States of America Michael Dietsch First Printing: September 2000 Indexer 02 01 00 4 3 2 Erika Millen Trademarks Proofreader Benjamin Berg All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or ser- vice marks have been appropriately capitalized. Que Corporation cannot Team Coordinator attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should Vicki Harding not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Design Manager Warning and Disclaimer Sandra Schroeder Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate Cover Designer as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. -

4.5.1 Los Abducidos: El Duro Retorno En Expediente X Se Duda De Si Las

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB 4.5.1 Los abducidos: El duro retorno En Expediente X se duda de si las abducciones son obra de humanos o de extraterrestres por lo menos hasta el momento en que Mulder es abducido al final de la Temporada 7. La duda hace que el encuentro con otras personas que dicen haber sido abducidas siempre tenga relevancia para Mulder, Scully o ambos, como se puede ver con claridad en el caso de Cassandra Spender. Hasta que él mismo es abducido se da la paradójica situación de que quien cree en la posibilidad de la abducción es él mientras que Scully, abducida en la Temporada 2, siempre duda de quién la secuestró, convenciéndose de que los extraterrestres son responsables sólo cuando su compañero desaparece (y no necesariamente en referencia a su propio rapto). En cualquier caso poco importa en el fondo si el abducido ha sido víctima de sus congéneres humanos o de alienígenas porque en todos los casos él o ella cree –con la singular excepción de Scully– que sus raptores no son de este mundo. Como Leslie Jones nos recuerda, las historias de abducción de la vida real que han inspirado este aspecto de Expediente X “expresan una nueva creencia, tal vez un nuevo temor: a través de la experimentación sin emociones realizada por los alienígenas usando cuerpos humanos adquiridos por la fuerza, se demuestra que el hombre pertenece a la naturaleza, mientras que los extraterrestres habitan una especie de supercultura.” (Jones 94). -

Cracking Software

Cracking software click here to download Using this, you can completely bypass the registration process by making it skip the application's key code verification process without using a valid key. In this Null Byte, let's go over how cracking could work in practice by looking at an example program (a program that serves. A few password cracking tools use a dictionary that contains passwords. These tools .. Looking for SSH login password crack software. Reply. This is just for learning. Softwares used: W32Dasm HIEW32 My New Tutorial Link - (Intro to Crackin using. HashCat claims to be the fastest and most advanced password cracking software available. Released as a free and open source software. In order to crack most software, you will need to have a good grasp on assembly, which is a low-level programming language. Assembly is derived from machine. The term crack is also commonly applied to the files used in software cracking programs, which enable illegal copying and the use of commercial software by. If your losst ypur passwords, you can try to crack your operating system and application passwords with various password‐cracking tools. LiveCD available to simplify the cracking.» Dumps and loads hashes from encrypted SAM recovered from a Windows partition.» Free and open source software. Hacking and Cracking -Software key and many more. 33K likes. HACKING TRICKS #PATCH SOFTWARE #ANDROID APPS PRO #MAC OS #WINDOWS APPS. Not everyone can crack a software because doing that requires a lot of computer knowledge but here we show you a logical method on how to. Crack means the act of breaking into a computer system. -

Warez All That Pirated Software Coming From?

Articles http://www.informit.com/articles/printerfriendly.asp?p=29894 Warez All that Pirated Software Coming From? Date: Nov 1, 2002 By Seth Fogie. Article is provided courtesy of Prentice Hall PTR. In this world of casual piracy, many people have forgotten or just never realized where many software releases originate. Seth Fogie looks at the past, present, and future of the warez industry; and illustrates the simple fact that "free" software is here to stay. NOTE The purpose of this article is to provide an educational overview of warez. The author is not taking a stance on the legality, morality, or any other *.ality on the issues surrounding the subject of warez and pirated software. In addition, no software was pirated, cracked, or otherwise illegally obtained during the writing of this article. Software piracy is one of the hottest subjects in today's computerized culture. With the upheaval of Napster and the subsequent spread of peer-to-peer programs, the casual sharing of software has become a world-wide pastime. All it takes is a few minutes on a DSL connection, and KazaA (or KazaA-Lite for those people who don't want adware) and any 10-year-old kid can have the latest pop song hit in their possession. As if deeply offending the music industry isn't enough, the same avenues taken to obtain cheap music also holds a vast number of software games and applications—some worth over $10,000. While it may be common knowledge that these items are available online, what isn't commonly known is the complexity of the process that many of these "releases" go through before they hit the file-sharing mainstream. -

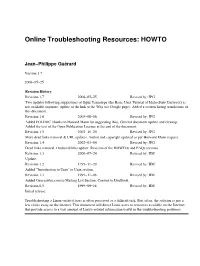

Online Troubleshooting Resources: HOWTO

Online Troubleshooting Resources: HOWTO Jean−Philippe Guérard Version 1.7 2006−05−25 Revision History Revision 1.7 2006−05−25 Revised by: JPG Two updates following suggestions of Oguz Yarimtepe (the Basic Unix Tutorial of Idaho State University is not available anymore, update of the link to the Why use Google page). Added a section listing translations of this document. Revision 1.6 2005−08−06 Revised by: JPG Added FOLDOC (thanks to Howard Mann for suggesting this). General document update and cleanup. Added the text of the Open Publication Licence at the end of the document. Revision 1.5 2002−10−20 Revised by: JPG More dead links removal & URL updates. Author and copyright updated as per Horward Mann request. Revision 1.4 2002−03−04 Revised by: JPG Dead links removal. Outdated links update. Revision of the HOWTOs and FAQs sections. Revision 1.3 2000−07−24 Revised by: HM Update. Revision 1.2 1999−11−20 Revised by: HM Added "Introduction to Unix" to Unix section. Revision 1.1 1999−11−08 Revised by: HM Added Geocrawler.com to Mailing List Section. Convert to DocBook. Revision 0.5 1999−09−18 Revised by: HM Initial release. Troubleshooting a Linux−related issue is often perceived as a difficult task. But, often, the solution is just a few clicks away on the internet. This document will direct Linux users to resources available on the Internet that provide access to a vast amount of Linux−related information useful in the troubleshooting problems. Online Troubleshooting Resources: HOWTO Table of Contents 1.