Dalit Versus Sub-Caste: a Study on the Problem of Identity of the Scheduled Castes of West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

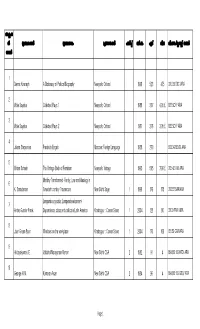

V. Aravindakshan 2.Xlsx

അക്സഷ ന് ഗര്ന്ഥകാരന് ഗര്ന്ഥനാമം പര്സാധകന് പതിപ്പ് വര്ഷംഏട്വിലവിഷയം/കല്ാസ്സ് നമ്പര് നമ്പര് 1 Dennis Kavnagh A Dictionary of Political Biography Newyork: Oxford 1998 523 475 320.092 DIC /ARA 2 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 1 Newyork: Oxford 1988 307 4.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 3 Wole Soyinka Collected Plays 2 Newyork: Oxford 1987 276 3.95 £ 822 SOY/ ARA 4 Jelena Stepanova Frederick Engels Moscow: Foreign Language 1958 270 923.343 ENG/ ARA 5 Miriam Schneir The Vintage Book of Feminism Newyork: Vintage 1995 505 7.99 £ 305.42 VIN/ ARA 6 Matriliny Transformed -Family, Law and Ideology in K. Saradamoni Twenteth century Travancore New Delhi: Sage 1 1999 176 175 306.83 SAR/ARA 7 Lumpenbourgeoisle: Lumpendevelopment- Andre Gunder Frank Dependence, class and politics in Latin America Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 128 80 320.9 FRA/ ARA 8 Joan Green Baun Windows on the workplace Khabagpur : Corner Stone 1 2004 170 100 651.59 GRA/ARA 9 Hridayakumari. E. Vallathol Narayanan Menon New Delhi: CSA 2 1982 91 4 894.812 109 HRD/ ARA 10 George. K.M. Kumaran Asan New Delhi: CSA 2 1984 96 4 894.812 109 GEO/ ARA Page 1 11 Tharakan. K.M. M.P. Paul New Delhi: CSA 1 1985 96 4 894.812 109 THA/ ARA 12 335.43 AJI/ARA Ajit Roy Euro-Communism' An Analytical story Calcutta: Pearl 88 10 13 801.951 MAC/ARA Archi Bald Macleish Poetry and Experience Australia: Penguin Books 1960 187 Alien Homage' -Edward Thompson and 14 891.4414 THO/ARA E.P. Thompson Rabindranath Tagore New Delhi : Oxford 2 1998 175 275 15 894.812309 VIS/ARA R.Viswanathan Pottekkatt New Delhi: CSA 1 1998 60 5 16 891.73 CHE/ARA A.P. -

Nobility Or Utility? Zamindars, Businessmen, and Bhadralok As Curators of Theindiannationinsatyajitray’S Jalsaghar ( the Music Room)∗

Modern Asian Studies 52, 2 (2018) pp. 683–715. C Cambridge University Press 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000482 First published online 11 December 2017 Nobility or Utility? Zamindars, businessmen, and bhadralok as curators of theIndiannationinSatyajitRay’s Jalsaghar ( The Music Room)∗ GAUTAM GHOSH The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The Bengali bhadralok have had an important impact on Indian nationalism in Bengal and in India more broadly. Their commitment to narratives of national progress has been noted. However, little attention has been given to how ‘earthly paradise’, ‘garden of delights’, and related ideas of refinement and nobility also informed their nationalism. This article excavates the idea of earthly paradise as it is portrayed in Satyajit Ray’s 1958 Bengali film Jalsaghar, usually translated as The Music Room. Jalsaghar is typically taken to depict, broadly, the decadence and decline of aristocratic ‘feudal’ landowners (zamindars) who were granted their holdings and, often, noble rank, such as ‘Lord’ or ‘Raja’, during Mughal or British times, representing the languid past of the nobility, and the ascendance of a ∗ Parts of this article were presented by invitation at the Asian Studies Centre, Oxford University; the South Asian Studies Centre, Heidelberg University, and the Borders, Citizenship and Mobility Workshop at King’s College London. Portions were also presented for the panel ‘Righteous futures: morality, temporality, and prefiguration’ organized by Craig Jeffrey and Assa Doron for the 2016 Australian Anthropological Society Meetings. -

K. Satchidanandan

1 K. SATCHIDANANDAN Bio-data: Highlights Date of Birth : 28 May 1946 Place of birth : Pulloot, Trichur Dt., Kerala Academic Qualifications M.A. (English) Maharajas College, Ernakulam, Kerala Ph.D. (English) on Post-Structuralist Literary Theory, University of Calic Posts held Consultant, Ministry of Human Resource, Govt. of India( 2006-2007) Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1996-2006) Editor (English), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1992-96) Professor, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1979-92) Lecturer, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1970-79) Lecturer, K.K.T.M. College, Pullut, Trichur (Dt.), Kerala (1967-70) Present Address 7-C, Neethi Apartments, Plot No.84, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110 092 Phone :011- 22246240 (Res.), 09868232794 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Other important positions held 1. Member, Faculty of Languages, Calicut University (1987-1993) 2. Member, Post-Graduate Board of Studies, University of Kerala (1987-1990) 3. Resource Person, Faculty Improvement Programme, University of Calicut, M.G. University, Kottayam, Ambedkar University, Aurangabad, Kerala University, Trivandrum, Lucknow University and Delhi University (1990-2004) 4. Jury Member, Kerala Govt. Film Award, 1990. 5. Member, Language Advisory Board (Malayalam), Sahitya Akademi (1988-92) 6. Member, Malayalam Advisory Board, National Book Trust (1996- ) 7. Jury Member, Kabir Samman, M.P. Govt. (1990, 1994, 1996) 8. Executive Member, Progressive Writers’ & Artists Association, Kerala (1990-92) 9. Founder Member, Forum for Secular Culture, Kerala 10. Co-ordinator, Indian Writers’ Delegation to the Festival of India in China, 1994. 11. Co-ordinator, Kavita-93, All India Poets’ Meet, New Delhi. 12. Adviser, ‘Vagarth’ Poetry Centre, Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Jnanpith Award * *

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * The Jnanpith Award (also spelled as Gyanpeeth Award ) is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa Kannada 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinkar Hindi Dattatreya Ramachandra Bendre Kannada 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi 1975 P. V. Akilan Tamil 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali 1977 K. Shivaram Karanth Kannada 1978 Sachchidananda Vatsyayan Hindi 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese 1980 S. K. Pottekkatt Malayalam 1981 Amrita Pritam Punjabi 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi 1983 Masti Venkatesha Iyengar Kannada 1984 Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati www.sirssolutions.in 91+9830842272 Email: [email protected] Please Post Your Comment at Our Website PAGE And our Sirs Solutions Face book Page Page 1 of 2 TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1986 Sachidananda Routray Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar (Kusumagraj) Marathi 1988 C. Narayanareddy Telugu 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 V. K. Gokak Kannada 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mahapatra Oriya 1994 U. -

Jalsaghar Cambridge.Pdf

Proof Delivery Form Modern Asian Studies Date of delivery: Journal and vol/article ref: ASS 1600048 Number of pages (not including this page): 32 This proof is sent to you on behalf of Cambridge University Press. Please print out the file and check the proofs carefully. Please ensure you answer all queries. Please EMAIL your corrections within 10 days of receipt to: Christine Cressy <[email protected]> Authors are strongly advised to read these proofs thoroughly because any errors missed may appear in the final published paper. This will be your ONLY chance to correct your proof. Once published, either online or in print, no further changes can be made. NOTE: If you have no corrections to make, please also email to authorise publication. • The proof is sent to you for correction of typographical errors only. Revision of the substance of the text is not permitted, unless discussed with the editor of the journal. Only one set of corrections are permitted. • Please answer carefully any author queries. • Corrections which do NOT follow journal style will not be accepted. • A new copy of a figure must be provided if correction of anything other than a typographical error introduced by the typesetter is required. • If you have problems with the file please email [email protected] Please note that this pdf is for proof checking purposes only. It should not be distributed to third parties and may not represent the final published version. Important: you must return any forms included with your proof. We cannot publish your article if you have not returned your signed copyright form Please do not reply to this email NOTE - for further information about Journals Production please consult our FAQs at http://journals.cambridge.org/production_faqs Author queries: Q1: The distinction between surnames can be ambiguous, therefore to ensure accurate tagging for indexing purposes online (eg for PubMed entries), please check that the highlighted surnames have been correctly identified, that all names are in the correct order and spelt correctly. -

Jnanpith Award

Jnanpith Award JNANPITH AWARD The Jnanpith Award is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English, with no posthumous conferral. The Bharatiya Jnanpith, a research and cultural institute founded in 1944 by industrialist Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain, conceived an idea in May 1961 to start a scheme "commanding national prestige and of international standard" to "select the best book out of the publications in Indian languages". The first recipient of the award was the Malayalam writer G. Sankara Kurup who received the award in 1965 for his collection of poems, Odakkuzhal (The Bamboo Flute), published in 1950. In 1976, Bengali novelist Ashapoorna Devi became the first woman to win the award and was honoured for the 1965 novel Pratham Pratisruti (The First Promise), the first in a trilogy. Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam (1st) 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali (2nd) 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati (3rd) 1967 Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa 'Kuvempu' Kannada (3rd) 1 Download Study Materials on www.examsdaily.in Follow us on FB for exam Updates: ExamsDaily Jnanpith Award 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi (4th) 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu (5th) 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu (6th) 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali (7th) 1972 Ramdhari Singh 'Dinkar' Hindi (8th) 1973 D. R. Bendre Kannada (9th) 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Odia (9th) 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi (10th) 1975 Akilan Tamil (11th) 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali (12th) 1977 K. -

From Quest for Justice to Dalit Identity: a New Look on the Crisis of Identity of the Scheduled Castes of West Bengal

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 8: March, 2015 ISSN : 2229-4880 From Quest for Justice to Dalit Identity: A New Look on the Crisis of identity of the Scheduled Castes of West Bengal Dr. Rup Kumar Barman• Abstract: In the recent years, it has become a common fashion among the social scientists, journalists and popular writers alike to classify the Scheduled Castes of India as Da/its. Being induced by the 'Dalit Panther movement' of the 1970 's, academics of both Dalit and non-Dalil social background; have reinterpreted the protests of the Scheduled Castes against upper castes' oppression and their writings under the banner of 'Dalit Discourse '. These trends eventually have encapsulated the Scheduled Castes within the/old of 'Dalit identity'. However, a major section of the Scheduled Castes of West Bengal has reservation to accept 'Dalit identity' what the Dalit writers and non-Dalit scholars are· trying to impose on them. Rather, they are more comfortable to be identified as Scheduled Castes in the society. This paper has analyzed that the social movement of the Scheduled Castes of late colonial Bengal is losing its dignity in the recent years because of classification of the Scheduled Castes merely as Dalils. Simultaneously the author has argued that 'construction of Da/it identity' of the Scheduled Castes is a theoretical imposition on theh1 at least in case of West Bengal. Key Words: Dalits, Dalitology, ScheduJed Castes Identity Dalit Studies, 'Da"lit Discourse.' From Quest for Justice to Dalit Identity: A New Look on the Crisis of identity of the Scheduled Castes of West Bengal In the rect:nt years, it has become a common fashion among the social scientists journalists and popular writers alike to classify the Scheduled Castes of India as Dalits. -

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR

Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature (CILL) CSR 1. Title and Commencement: 1.1 These Regulations shall be called THE REGULATIONS FOR SEMESTERISED M.A. in Comparative Indian Language and Literature Post- Graduate Programme (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) 2018, UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA. 1.2 These Regulations shall come into force with effect from the academic session 2018-2019. 2. Duration of the Programme: The 2-year M.A. programme shall be for a minimum duration of Four (04) consecutive semesters of six months each/ i.e., two (2) years and will start ordinarily in the month of July of each year. 3. Applicability of the New Regulations: These new regulations shall be applicable to: a) The students taking admission to the M.A. Course in the academic session 2018-19 b) The students admitted in earlier sessions but did not enrol for M.A. Part I Examinations up to 2018 c) The students admitted in earlier sessions and enrolled for Part I Examinations but did not appear in Part I Examinations up to 2018. d) The students admitted in earlier sessions and appeared in M.A. Part I Examinations in 2018 or earlier shall continue to be guided by the existing Regulations of Annual System. 4. Attendance 4.1 A student attending at least 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. 4.2 A student attending at least 60% but less than 75% of the total number of classes* held shall be allowed to sit for the concerned Semester Examinations subject to the payment of prescribed condonation fees and fulfilment of other conditions laid down in the regulations. -

Bengali Language Handbook

R E- F 0 R T RESUMES ED 012 911 48 AL 000 604 BENGALI LANGUAGE HANDBOOK. BY- RAY, FUNYA SLOKA AND. OTHERS CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, WASHINGTON, D.C. REPORT NUMBER BR-5 -1242 PUB DATE 66' CONTRACT OEC -2 -14 -042 EDRS PRICE MF$0.75 HC-$6.04 15IF. DESCRIPTORS-*BENGALI, *REFERENCE BOOKS, LITERATURE GUIDES, CONTRASTIVE LINGUISTICS, GRAMMAR, PHONETICS, CULTURAL BACKGROUND, SOCIOLINGUISTICS, WRITING, ALPHABETS, DIALECT STUDIES, CHALIT, SADHU, INDIA, WEST BENGAL, EAST PAKISTAN, THIS VOLUME OF THE LANGUAGE HANDBOOK SERIES IS INTENDED TO SERVE AS AN OUTLINE OF THE SALIENT FEATURES OF THE BENGALI LANGUAGE SPOKEN BY OVER 80 MILLION PEOPLE IN EAST PAKISTAN AND INDIA. IT WAS WRITTEN WITH SEVERAL READERS IN MIND-.-(1) A -LINGUIST INTERESTED IN BENGALI BUT NOT HIMSELF A SPECIALIST INTHE LANGUAGE,(2) AN INTERMEDIATE OR ADVANCED STUDENT WHO WANTS A CONCISE'GENERAL PICTURE OF THELANGUAGE AND ITS SETTING, AND (3) AN AREA SPECIALIST WHO NEEDS BASIC LINGUISTIC OR SOCIOLINGUISTIC FACTS ABOUT THE AREA. CHAPTERS ON THE LANGUAGE SITUATION, PHONOLOGY, AND ORTHOGRAPHY. PRECEDE THE LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX. ALTHOUGH THE LINGUISTIC DESCRIPTION IS NOT INTENDED TO BE DEFINITIVE, IT USES TECHNICAL TERMINOLOGY AND ASSUMES THE READER HAS PREVIOUS KNOWLEDGE OF LINGUISTICS. STRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES 'BETWEEN BENGALI AND AMERICAN ENGLISH ARE DISCUSSED AS ARE THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SADHU STANDARD AND CHALIT STANDARD BENGALI. THE DACCA DIALECT AND THE CHITTAGONG DIALECT ARE BRIEFLY TREATED AND THEIR GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION IS SHOWN ON A MAP OF BENGALI DIALECTS. FINAL CHAPTERS SURVEY THE . HISTORY OF BENGALI LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND LITERARY CRITICISM. THIS HANDBOOK IS ALSO AVAILABLE FOR $3.00 FROM THE CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, 1717 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, WW., WASHINGTON, D.C., 20036. -

Cjns Lib,2017

Catalogue of Books- 2017 S.No. Author Titles of the Books Year Call No. Vol Acc. No 1 A Ambirajan Classicial Political Economy and British Policy in India. 1978 330.95403 AMB 242675 2 A C. Aewing Falsafa ke Bunyadi Masail. 1978 181 EYO G-254420 3 A Fadeyev Young Guard. 1953 891.73 FAD G-256533 4 A G Noorani Indian Poliotical Trials 1775-1947. 2005 954.03 NOO 240887 5 Jawaharlal Nehru: Vommunicator and Democratic A K Damodaran Leader. 1997 954.04092 DAM 240259 6 A K Dasgupta, Arun Ghosh Religion, Secularism and Conversion in India. 2010 362.8027 REL 269942 7 A P Joshi M.D. Srinivas a & J K Bajaj Religious Demography of India 2001 Revision. 2005 304.60954 JOS 241451 8 A Punjabi Confedracy of India. 1939 821.0254 PUN G-255944 9 A Ramakrishna Rao Krishnadevaraya. 1995 809.95392 RAO G-254214 10 Constitution of Jammu & Kashmir Its Development & A S Anand Comments. 2007 342.0954602 ANA 244900 11 A S. Kompaneyets Theoretical Physic. 1965 530 KOM G-254139 12 A. A. Engineer Marjit S.Narang Ed. Minorities & Police in India. 2006 305.560954 MIN 241962 13 A. Alvarez New Poetry. 1962 321 LAV G-255538 14 A. Appadorai Essyas in Politics and International Relations. 1969 327.1 APP 242448 15 A. Arshad Sami Khan Sj. Three presidents and an Life, Power & Politics. 2008 321.095491092 KHA 244666 16 A. Aspinall et al. Parliament through Seven Centuries. 1962 328.09 PAR G-255458 17 A. Berriedale Keith Speeches & Document on Indian Policy 1750- 1921 1945 320.954 KEI G-254808 18 A. -

Awards & Honor 2020

Awards & Honours Awards & Honor 2020 PDF Recommendations Sarkari Naukuri Employment News Central Government Jobs Government Jobs State Government Jobs Recruitment.guru https://www.recruitment.guru/general-knowledge-questions/ Awards & Honours Bharat Ratna - Awards and Honours Questions It is the highest civilian award in India. The award is given in recognition of service of the highest order, without distinction of race, occupation, position, or sex. The award was originally given to achievements in the arts, literature, science, and public services, but was later included other fields. The recommendations for the Bharat Ratna are made by the Prime Minister with a maximum of three nominees given the award per year. Recipients receive a Sanad (certificate) signed by the President and a peepal-leaf–shaped medallion. Recipients Year C Rajagopalachari Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan 1954 C V Raman Bhagwan Das M Visvesvaraya 1955 Jawaharlal Nehru Govind Ballabh Pant 1957 Dhondo Keshav Karve 1958 Bidhan Chandra Roy 1961 Purushottam Das Tandon Rajendra Prasad 1962 Zakir Husain 1963 Pandurang Vaman Kane Lal Bahadur Shastry 1966 Indira Gandhi 1971 V V Giri 1975 https://www.recruitment.guru/general-knowledge-questions/ Awards & Honours K Kamaraj 1976 Mother Teresa 1980 Vinoba Bhave 1983 Khan Abdul Ghaffar 1987 M G Ramachandran 1988 B R Ambedkar Nelson Mandela 1990 Rajiv Gandhi Vallabhbhai Patel 1991 Moraji Desai Abul Kalam Azad J R D Tata 1992 Satyajit Ray Gulzarilal Nanda Aruna Asaf Ali 1997 A P J Abdul Kalam M S Subbulakshmi 1998 Chidambaram Subramaniam Amartya Sen Gopinath Bordoloi 1999 Ravi Shankar Lata Mangeshkar 2001 Bismillah Khan https://www.recruitment.guru/general-knowledge-questions/ Awards & Honours Bhimsen Joshi 2009 C N R Rao 2014 Sachin Tendulkar Madan Mohan Malaviya 2015 Atal Bihari Vajpayee Nanaji Deshmukh Bhupen Hazarika 2019 Pranab Mukherjee Jnanapith Awards - Awards and Honours Questions The Jnanpith Award is an Indian literary award presented by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to writers.