Glee Confronts Hetero-Normativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experience Glee

FREE YOUR A three-week Newspapers In Education program in partnership gleewith The Puyallup Fair Jingle History What is Find (and A jingle can be thought of as a musical commercial. Jingles began in the 1920s, about the time commercial radio became popular in the United States. Most jingles you hear on radio and television tend to be share!) your short and upbeat (all the better to get stuck in your head!) They are designed to make you feel happy and associate good feelings with the product they are advertising. They are often fun and easy to sing glee? — some jingles are so catchy that they become part of our cultural memory, something that everyone from a particular time and place What is the first thing you think of when you hear glee might remember. the word “glee?” You may think of the feelings The “Do the Puyallup” jingle has celebrated the Fair since 1976. associated with glee, or feeling “gleeful,” which Originally it was a slogan created by famed advertising copywriter can be described as extremely happy. Or your first Denny Hinton. Fellow copywriter Saxon Rawlings got out his guitar, thoughts might be of a “glee club,” a group of started writing lyrics and the rest is history. The Fair loved it. And it singers like the ones in the television show Glee. became a hit. The jingle has been sung in a variety of styles, including There is no correct answer to this question — glee rock, country or gospel. Listen to different versions on the Fair website: means different things to different people. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Who's Telling My Story?

LESSON PLAN Level: Grades 9 to 12 About the Author: Matthew Johnson, Director of Education, MediaSmarts Duration: 2 to 3 hours This lesson was produced with the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Justice Canada's Justice Partnership and Innovation Program. Who’s Telling My Story? This lesson is part of USE, UNDERSTAND & CREATE: A Digital Literacy Framework for Canadian Schools: http://mediasmarts.ca/teacher-resources/digital-literacy-framework. Overview In this lesson students learn about the history of blackface and other examples of majority-group actors playing minority -group characters such as White actors playing Asian and Aboriginal characters and non-disabled actors playing disabled characters. They consider the key media literacy concepts that “audiences negotiate meaning” and “media contain ideological and value messages and have social implications” in discussing how different kinds of representation have become unacceptable and how those kinds of representations were tied to stereotypes. Finally, students discuss current examples of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters and write and comment on blogs in which they consider the issues raised in the lesson. Learning Outcomes Students will: learn about the history and implications of majority-group actors playing minority-group characters consider the importance of self-representation by minority communities in the media state and support an opinion write a persuasive essay Preparation and Materials Read Analyzing Blackface (Teacher’s Copy) Prepare to show the A History of Blackface slideshow and Blackface Then and Now video to the class Copy the following handouts: Analyzing Blackface Cripface www.mediasmarts.ca 1 © 2016 MediaSmarts Who’s Telling My Story? ● Lesson Plan ● Grades 9 – 12 Procedure Begin by projecting the first two images from “A History of Blackface”: Carlo Rota and Kevin McHale, from series currently on TV (2011). -

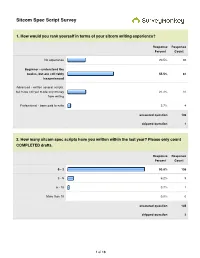

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for Artistic Achievement

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for artistic achievement WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson is a native of the Pacific Northwest who has shown that even through adversity and hardship, one can make their dreams come true; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in films such as the Academy Award nominated United 93, the Sundance selected Price Check, and The Green; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has also appeared on television programs such as Glee, Ugly Betty, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and 30 Rock; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in such Broadway and off-Broadway productions as All Shook Up, The Agony and The Agony, The Heart of the Matter, and 8; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has recorded two studio albums and has sold out Carnegie Hall twice; and WHEREAS, his work on Broadway, on television, in film and his activism on behalf of the LGBT community through his work with the Foundation for AIDS research and the Hetrick-Martin Institute which supports LGBT youth have been a source of inspiration for many in our community; and WHEREAS, we are proud to welcome Cheyenne Jackson back to the Pacific Northwest for his performance at Martin Woldson Theater in the hopes that his work will inspire many more; NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, by the Spokane City Council that we hereby salute Cheyenne Jackson for all of his accomplishments and look forward to his performance with the Spokane Symphony. I, Ben Stuckart, Spokane City Council President, do hereunto set my hand and cause the seal of the City of Spokane to be affixed this 19th day of May in 2014 Ben Stuckart Spokane City Council President . -

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club The Morehouse College Glee Club is the premier singing organization of Morehouse College, traveling all over the country and the world, demonstrating excellence not only in choral performance but also in discipline, dedication, and brotherhood. Through its tradition the Glee Club has an impressive history and seeks to secure its future through even greater accomplishments, continuing in this tradition through the dedication and commitment of its members and the leadership that its directors have provided throughout the years. It is the mission of the Morehouse College Glee Club to maintain a high standard of musical excellence. In 1911, Morehouse College, then under the name of Atlanta Baptist College, had a music professor named Georgia Starr. She served the College from 1903-1905 and again from 1908- 1911. Mr. Kemper Harreld, who officially founded the Morehouse College Glee Club, assumed leadership when he joined the College’s music faculty in the fall of 1911. Mr. Harreld became both, Chair of the Music Department and Director of the Glee Club. After faithfully serving for forty-two years, he retired in 1953. Mr. Harreld was responsible for beginning the Glee Club’s strong legacy of excellence that has since been passed down to all members of the organization. The Glee Club’s history continues in 1953 with the second director, Wendell Phillips Whalum, Sr., '52. Dr. Whalum was a prized student of Kemper Harreld. He served as Student Director during his tenure in the Glee Club. Dr. Whalum, was more commonly known as "Doc", and served Morehouse College and the Glee Club with the continued tradition of excellence through expanded repertoire and national and international exposure throughout his tenure at the College. -

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition Results Tenor 1

Rutgers University Glee Club Fall 2020 – Audition results Congratulations and welcome to the start of a great new year of music making. Please register for the Rutgers University Glee Club immediately – Course 07 701 349. If you are a music major and have any issues with registration please contact Ms. Leibowitz. Non majors with questions please email Dr. Gardner – [email protected]. Glee Club rehearases on Weds nights from 7 to 10 pm and Fridays from 2:50 to 4:10 pm on-line. The zoom link and syllabus is available in Canvas. First rehearsal is this coming Wednesday, September 9th. See you there! Tenor 1 Tenor 2 Baritone Bass Maxwell Domanchich Billy Colletto III Ryan Acevedo James Carson Tin Fung Sean Dekhayser Kyle Cao John DeMarco Jonathan Germosen Steve Franklin Jeffrey Greiner Duff Heitmann Joseph Maldonado James Hwang Tristan Kilper Jonathan Ho Khuti Moses Benjamin Kritz Brian Kong Emerson Katz-Justice Aditya Nibhanupudi Matthew Mallick Matthew Lacognata Seonuk Kim Michael O'Neill Amartya Mani Michael Lazarow Allen Li Michael Schaming Gene Masso Ryan Leibowitz Gabriel Lukijaniuk Xerxes Tata Conor Wall Carl Muhler Sean McBurney Harry Thomas Bobby Weil Julian Perelman Joseph Mezza Zachary Wang John Wilson Caleb Schneider AJ Pandey Nathaniel Barnett Samuel Wilson Gianmarco Scotti Thomas Piatkowski Josh Gonzalez Patrick Cascia Kolter Yagual-Ralston Guillermo Pineiro Kyle Casem Nicholas Casey Nathaniel Eck Ross Ferguson Sachin Boteju Mike Semancik Michael Munza Evan Dickonson Soroush Gharavi Jason Bedianko Colin Smith Benjamin Shanofsky . -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

The Medley Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2010 October 17, 2010 Editor: Jessica Trask

The Medley Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2010 October 17, 2010 Editor: Jessica Trask Visit us soon at www.wgc.osu.edu! Email us at [email protected] Announcements Upcoming Dates Get ready for Halloween! Start thinking about your Friday, Oct. 29th at 8pm: HalleBOOia! Concert Halloween costume, as all performers at the HalleBOOia! concert are expected to wear a costume Monday, Nov. 8th at 7:30pm: Concert with or all black. Most people wear costumes, so have fun Kent State Women's Chorus with it! See page 2 for more details. Saturday, Nov. 13th (time TBA): Sing at Hem your dresses! When dresses come in you are responsible for getting them hemmed as soon as President's Brunch possible. If you can't get it hemmed before the November 8th concert, talk to Vice PResident Sunday, Nov. 14th at 3pm: Concert with WGC Shannon Tarbutton(.4) about a "quick-fix". Don't forget that Ashley Donmoyer(.6) will hem for a small fee! President's Brunch Gig 11/13 We have been invited to sing at the President's Brunch before the football game of November 13th. Report is TBA, so try Musical Words of Wisdom to keep your schedule clear if possible! This is always a fun gig because people love us! Remember, information is not knowledge; knowledge is not wisdom; wisdom is not truth; truth is not beauty; beauty is not love; love is not music; music is the best. ~ Frank Zappa In This Issue A few highlights to look for... Presidential Welcome....................................................2 Conductor's Corner........................................................2 Glee MadLib!.................................................................3 HalleBOOia Concert info...............................................3 Kick-Off Retreat: A Success!.........................................4 "Our Best, Ohio": Behind the Music..............................5 First WGC Tailgate: OSU vs.