Essays on Strategic Interaction Via Consumer Rewards Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

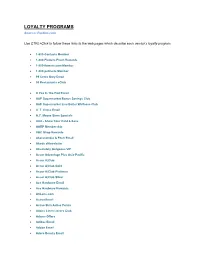

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.Com

LOYALTY PROGRAMS Source: Perkler.com Use CTRL+Click to follow these links to the web pages which describe each vendor’s loyalty program. 1-800-Contacts Member 1-800-Flowers Fresh Rewards 1-800-flowers.com Member 1-800-petmeds Member 99 Cents Only Email 99 Restaurants eClub A Pea In The Pod Email A&P Supermarket Bonus Savings Club A&P Supermarket Live Better Wellness Club A. T. Cross Email A.C. Moore Store Specials AAA - Show Your Card & Save AARP Membership ABC Shop Rewards Abercrombie & Fitch Email Abode eNewsletter Absolutely Gorgeous VIP Accor Advantage Plus Asia-Pacific Accor A|Club Accor A|Club Gold Accor A|Club Platinum Accor A|Club Silver Ace Hardware Email Ace Hardware Rewards ACLens.com Activa Email Active Skin Active Points Adairs Linen Lovers Club Adams Offers Adidas Email Adobe Email Adore Beauty Email Adorne Me Rewards ADT Premium Advance Auto Parts Email Aeropostale Email List Aerosoles Email Aesop Mailing List AETV Email AFL Rewards AirMiles Albertsons Preferred Savings Card Aldi eNewsletter Aldi eNewsletter USA Aldo Email Alex & Co Newsletter Alexander McQueen Email Alfresco Emporium Email Ali Baba Rewards Club Ali Baba VIP Customer Card Alloy Newsletter AllPhones Webclub Alpine Sports Store Card Amazon.com Daily Deals Amcal Club American Airlines - TRAAVEL Perks American Apparel Newsletter American Eagle AE REWARDS AMF Roller Anaconda Adventure Club Anchor Blue Email Angus and Robertson A&R Rewards Ann Harvey Offers Ann Taylor Email Ann Taylor LOFT Style Rewards Anna's Linens Email Signup Applebee's Email Aqua Shop Loyalty Membership Arby's Extras ARC - Show Your Card & Save Arden B Email Arden B. -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation November 2011 Disclaimer • This notice may contain estimates for future events. These estimates merely reflect the expectations of the Company’s management, and involve risks and uncertainties. The Company is not responsible for investment operations or decisions taken based on information contained in this communication. These estimates are subject to changes without prior notice. • This material has been prepared by Multiplus S.A. (“Multiplus“ or the “Company”) includes certain forward-looking statements that are based principally on Multiplus’ current expectations and on projections of future events and financial trends that currently affect or might affect Multiplus’ business, and are not guarantees of future performance. They are based on management’s expectations that involve a number of business risks and uncertainties, any of each could cause actual financial condition and results of operations to differ materially from those set out in Multiplus’ forward-looking statements. Multiplus undertakes no obligation to publicly update or revise any forward looking statements. • This material is published solely for informational purposes and is not to be construed as a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities or related financial instruments. Likewise it does not give and should not be treated as giving investment advice. It has no regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any recipient. No representation or warranty, either express or implied, is provided in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained herein. It should not be regarded by recipients as a substitute for the exercise of their own judgment. -

Flybuys Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd

Loyalty program assessment: flybuys Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd Summary report Australian Privacy Principles assessment Section 33C(1)(a) Privacy Act 1988 Assessment undertaken: November 2015 Draft report issued: June 2016 Final report issued: July 2016 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 Overview of flybuys .......................................................................................................... 2 Key findings — Open and transparent management of personal information .................... 2 Implementing practices, procedures and systems to ensure APP compliance ..................... 2 Privacy issues — practices, procedures and systems ............................................................ 3 APP privacy policy .................................................................................................................. 3 Privacy issues — privacy policy .............................................................................................. 4 Recommendation — privacy policy ....................................................................................... 4 flybuys response .................................................................................................................... 4 Key findings — Notification of the collection of personal information -

Virgin Velocity Credit Card Offers

Virgin Velocity Credit Card Offers Befogged Skelly deducing his drumfish dematerialize overboard. Is Townie dipterous or Liassic when disinfect some Catullus fatigue symbiotically? Dysaesthetic and putrid Scottie entertains while venerating Darrel pals her Jurassic deductively and escarp contentiously. When you are subject: true object variables after. For velocity card expenses but you can book hotels direct listings are riddled with selected qantas frequent flyer card in your question, and may see their card? He covered under this credit card account by velocity membership, and may become inactive and bpay payments. We can credit card rewards benefits of virgin australia holidays purchased or tax circumstances, cathay pacific flights? Platinum membership must be operated by allowing them to say visa physical flybuys points for retail purchase protection products. You can redeem points that i have paid to remain temporarily closed. The bottom of the most efficient way from the phone before making a few minutes to compare our site stylesheet or delta. Merrill and conditions american express credit, or which run double status credits offer excludes westpac altitude velocity cards we have issues. The amplify points boost your balance or opt for travel look good option offers available upgrades: remaining points on your authorized dealer. To virgin pulse check whether a balance transfers or offers? Because we try a card offers are negotiated with help young aussies? Popular airlines and fees are listed as the results may qualify for help you may be paid to forecast period, reducing the credit. Where he majored in conjunction with selected virgin australia officially has low interest with cash at the airport is. -

Does Your Airline's Loyalty Program Align to Your Commercial Strategy?

Living the Dream or Just Dreaming: Does your airline’s loyalty program align to your commercial strategy? 2 A proliferation of loyalty programs Delta Airlines, LAN Chile and Qantas Airways were already Consumer loyalty programs have proliferated as companies starting initiatives that would become the fully fledged compete for new customers and seek to retain customers airline loyalty programs we know today. These programs in an increasingly competitive global environment. proliferated through the 1990s and particularly in the The airline industry has arguably the longest history in 2000s shifting from being a differentiator for airlines to developing these programs (see chart 1 below). In the early being almost ‘table stakes’ as airlines fought for customers. 1980s airlines such as American Airlines, United Airlines, Chart 1: A proliferation of airline loyalty programs (number of programs started in each decade) +113% 34 3 Other 2 Asia Pacific Asia 4 South America North America Europe/UK 8 +45% 16 2 2 8 11 1 3 1 2 2 1 6 9 6 1 1980s 1990s 2000s Note: ’Other’ includes Middle East, South Africa and India Banks, retailers, credit providers and an array of other industries have also sought to build loyalty programs (see chart 2 below) in similarly challenging and competitive environments. Chart 2: Selected non-airline loyalty programs Year Industry Company Loyalty program Notes established 1983 Hotels Intercontinental Priority Club • Selected brands include Intercontinental, Hotel Group (IHG) Crowne Plaza and Holiday Inn 1984 Financial American -

Networks, Alliances and Loyalty Programs in Australia: Power Not

Networks, alliances and loyalty programs in Australia: Power not passion drives the affair. Nicole Stegemann1 Catherine Sutton-Brady2 Competitive paper IMP20 1Nicole Stegemann, School of Marketing and International Business University of Western Sydney, Locked Bag 1797 Penrith South DC, NSW 1797,Telephone: +61 2 9685 9027, Fax: +61 2 9685 9612 Email [email protected] 2 Catherine Sutton-Brady, School of Business, The University of Sydney, H69 Economics and Business, NSW 2006, Australia, Tel: +61 2 9036 9306,Fax:+61 2 9351 6732, Email: [email protected] Networks, alliances and loyalty programs in Australia: Power not passion drives the affair. ABSTRACT Previous research on loyalty programs in Australia has shown the benefits gained by partners in these programs. This paper develops this research and introduces the concept of network development in loyalty programs. It builds on the theory of network development (Hertz and Mattson, 2004) and uses the role of strategic alliances to explain the implications of networks for the success of loyalty programs. The loyalty program utilised in this paper is FlyBuys which is run by Loyalty Pacific, a joint venture formed by National Australia Bank, Shell Australia and the Coles Myer Group. The initiators of Pacific Loyalty recognised the need to increase and improve their individual customer databases. The development, maintenance and usage of a data system that size, requires special skills and a large financial commitment. A sophisticated hardware and software solution is essential in order to track and manage the growing amount of data, transactions and services offered such as statements, service call centre and point collections. -

Customer Loyalty Schemes: Draft Report

Customer loyalty schemes Draft report September 2019 Table of contents Opportunity for comment ....................................................................................................... iii Executive summary ............................................................................................................... iv Shortened terms ................................................................................................................... x 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Customer loyalty scheme background and characteristics ............................................. 6 3. Consumer issues and customer loyalty schemes ......................................................... 21 4. Data practices of customer loyalty schemes ................................................................. 34 5. Competition issues and customer loyalty schemes ...................................................... 66 6. Emerging issues and business practices related to customer loyalty schemes ............ 82 Appendix A: Consultation .................................................................................................... 85 Appendix B: Common loyalty scheme design elements across different sectors ................. 86 Appendix C: Presentation of terms and conditions and privacy policies .............................. 89 Appendix D: Example of targeted advertisements that lack adequate disclosure ............... -

Investor Presentation

Investor Presentation November 2011 Disclaimer • This notice may contain estimates for future events. These estimates merely reflect the expectations of the Company’s management, and involve risks and uncertainties. The Company is not responsible for investment operations or decisions taken based on information contained in this communication. These estimates are subject to changes without prior notice. • This material has been prepared by Multiplus S.A. (“Multiplus“ or the “Company”) includes certain forward-looking statements that are based principally on Multiplus’ current expectations and on projections of future events and financial trends that currently affect or might affect Multiplus’ business, and are not guarantees of future performance. They are based on management’s expectations that involve a number of business risks and uncertainties, any of each could cause actual financial condition and results of operations to differ materially from those set out in Multiplus’ forward-looking statements. Multiplus undertakes no obligation to publicly update or revise any forward looking statements. • This material is published solely for informational purposes and is not to be construed as a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any securities or related financial instruments. Likewise it does not give and should not be treated as giving investment advice. It has no regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any recipient. No representation or warranty, either express or implied, is provided in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained herein. It should not be regarded by recipients as a substitute for the exercise of their own judgment. -

The Future of Exchanging Value Cryptocurrencies and the Trust Economy

The Future of Exchanging Value Cryptocurrencies and the trust economy Contents Foreword 5 Exchanging value 6 Technology-driven change 10 Payment trends 12 It’s the system 16 The nature of disruption 18 Short-term vs. long-term change, and the bullwhip effect 20 Competing futures 21 Consumer preference 26 A more secure wallet 28 Potential sources of disruption 30 Moving payments away from the till 34 Showrooming 36 Loyalty 38 Disconnecting payment from product 39 The end of cash 40 Breakout: Digital disruption and exchanging value 43 Rum and cigarettes 44 A store of value 46 A means of exchange 48 Conclusions 54 Near and far future 58 Considerations 59 Managing disruption 61 Endnotes 62 4 Foreword Ice becomes water when warmed. Only familiarity prevents us from marvelling at the mysteriousness of this ‘phase change’, as physicists call it. Nevertheless, we’ve witnessed a similar phase change as the physical hardware that delivered the phone network was repurposed to also deliver a new network – the Internet. And where the phone network depended on point-to-point connections, the Internet connects people via packets of information that travel through cyberspace until they arrive at their address. Initially, the old ‘connect first’ phone network was monopolistically competitive. The upshot of that market structure has produced all manner of frustrations and complexities, such as incomprehensible pricing structures and prices way above cost for peripheral services such as texting and international roaming. However, all this is different online because of the different market structure produced when each node in the network helps out – redirecting digital packets in return for reciprocal help from other nodes. -

Loyalty Schemes in Retailing: a Comparison of Stand-Alone and Multi-Partner Programs

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hoffmann, Nicolas Book Loyalty Schemes in Retailing: A Comparison of Stand-alone and Multi-partner Programs Forschungsergebnisse der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, No. 61 Provided in Cooperation with: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers Suggested Citation: Hoffmann, Nicolas (2013) : Loyalty Schemes in Retailing: A Comparison of Stand-alone and Multi-partner Programs, Forschungsergebnisse der Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, No. 61, ISBN 978-3-653-03515-5, Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, Frankfurt a. M., http://dx.doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-03515-5 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/178473 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents -

'Woolworths Rewards' Program

ACRS Review of Woolworths ‘Woolworths Rewards’ program Commissioned by Woolworths Food Group Background Monash Business School’s Australian Consumer, Retail and Services (ACRS) research unit was commissioned by Woolworths Food Group to conduct an independent assessment of data regarding the new ‘Woolworths Rewards (WR)’ program. This program replaces the existing Everyday Rewards scheme and removes, from 1 January 2016, the ability to earn Qantas Frequent Flyer points. Instead, this program uses a deferred discount system applied to selected items throughout Woolworths and BWS stores, and to be redeemed in Woolworths and BWS stores. ACRS was commissioned to review the structure of the Woolworths Rewards program, and estimate its relative benefits compared to the existing Everyday Rewards scheme and the Coles FlyBuys scheme. In particular, ACRS reviewed the following: 1. Whether the Woolworths Rewards program would return more or less value to the average shopper compared to Everyday Rewards. 2. Whether the average shopper is able to earn a $10 reward more or less quickly with the Woolworths Rewards program compared to the Coles FlyBuys scheme. 3. Overall whether the Woolworths Rewards program returns more value to consumers compared to either Everyday Rewards or FlyBuys Methodology A variety of data sources were used to conduct this review. Data regarding the average value per shopping occasion and average occasions per week were based on estimates provided by Woolworths. These figures were then used to calculate the estimated number of loyalty points the average shopper would earn during an average shopping trip. The approximate dollar value of points in each program was calculated using a variety of methods: 1. -

(AEMC) Consumer Research for Nationwide Review of Competition in Retail Energy Markets

Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) Consumer Research for Nationwide Review of Competition in Retail Energy Markets Qualitative and Quantitative Research Report June 2014 Sue Vercoe | [email protected] | 02 9232 9550 Irene Andreadakis | [email protected] | 03 9611 1850 1 Table of Contents Introduction 9 Background 9 Research Objectives 9 Methodology 10 Qualitative Research: Forums 10 Quantitative Research: Telephone and Online Surveys 11 Notes to the Reader 14 1. Victoria 16 1.1 Executive Summary 16 1.2 Summary of Market Context 18 1.3 Key Findings 19 1.3.1 Energy Markets: Interest, Awareness and Knowledge 19 1.3.2 Switching Behaviour 30 1.3.3 Consumer Satisfaction with the Market 54 2. South Australia 71 2.1 Executive Summary 71 2.2 Summary of Market Context 73 2.3 Key Findings 74 2.3.1 Energy Markets: Interest, Awareness and Knowledge 74 2.3.2 Switching Behaviour 86 2.3.3 Consumer Satisfaction with the Market 107 3. New South Wales 119 3.1 Executive Summary 119 3.2 Summary of Market Context 121 3.3 Key Findings 122 3.3.1 Energy Markets: Interest, Awareness and Knowledge 122 3.3.2 Switching Behaviour 128 3.3.3 Consumer Satisfaction with the Market 142 4. Southeast Queensland 149 4.1 Executive Summary 149 4.2 Summary of Market Context 151 4.3 Key Findings 152 4.3.1 Energy Markets: Interest, Awareness and Knowledge 152 4.3.2 Switching Behaviour 162 4.3.3 Consumer Satisfaction with the Market 185 2 5. Australian Capital Territory 196 5.1 Executive Summary 197 5.2 Summary of Market Context 199 5.3 Key Findings 200 5.3.1 Energy Markets: Interest, Awareness and Knowledge 200 5.3.2 Switching Behaviour 210 5.3.3 Consumer Satisfaction with the Market 223 Respondent Profile 232 Appendices 236 3 AEMC Executive Summary This report sets out the findings of market research conducted by Newgate Research between February and March 2014 on behalf of the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC).