Lincoln the Profiler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech'

H-FedHist White on Conant, 'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech' Review published on Monday, September 18, 2017 Sean Conant, ed. The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. xvi + 350 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-19-022745-6; $79.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-022744-9. Reviewed by Jonathan W. White (Christopher Newport University)Published on H-FedHist (September, 2017) Commissioned by Caryn E. Neumann When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton read the Gettysburg Address to a Republican rally in Pennsylvania in 1868, he declared triumphantly, “That is the voice of God speaking through the lips of Abraham Lincoln!”[1] Indeed, the speech has become akin to American scripture. This collection of essays, now available in paperback, was originally put together to accompany a film titledThe Gettysburg Address (2017), which was produced by the editor of this book, Sean Conant. It brings “a new birth of fresh analysis for those who still love those words and still yearn to better understand them,” writes Harold Holzer in the foreword (p. xv). The volume is broken up into two parts: “Influences” and “Impacts,” with chapters from a number of notable Lincoln scholars and Civil War historians. The opening essay, by Nicholas P. Cole, challenges Garry Wills’s interpretation of the address, offering the sensible observation that “rather than setting Lincoln’s words in the context of Athenian funeral oratory, it is perhaps more natural to explain both the form of Lincoln’s words and their popular reception at the time in the context of the Fourth of July orations that would have been immediately familiar to both Lincoln and his audience” (p. -

The Lincoln Assassination: Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory

LincolnThe Assassination CRIME&PUNISHMENT, MYTH& MEMORY edited by HAROLD HOLZER, CRAIG L. SYMONDS & FRANK J. WILLIAMS A LINCOLN FORUM BOOK The Lincoln Assassination ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:09:42 PS PAGE i ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:36 PS PAGE ii T he L incoln Forum The Lincoln Assassination Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York • 2010 ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:37 PS PAGE iii Frontispiece: A. Bancroft, after a photograph by the Mathew Brady Gallery, To the Memory of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States . Lithograph, published in Philadelphia, 1865. (Indianapolis Museum of Art, Mary B. Milliken Fund) Copyright ᭧ 2010 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Lincoln assassination : crime and punishment, myth and memory / edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams.—1st ed. p. cm.— (The North’s Civil War) ‘‘The Lincoln Forum.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8232-3226-0 (cloth : alk. -

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor. -

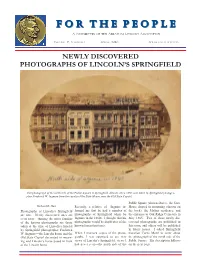

F O R T H E P E O P

FF oo rr TT hh ee PP ee oo pp ll ee A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1 SPRING 2010 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS NEWLY DISCOVERED PHOTOGRAPHS OF LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD This photograph of the north side of the Public Square in Springfield, Illinois, circa 1860, was taken by Springfield photogra- pher Frederick W. Ingmire from the cupola of the State House, now the Old State Capitol. Public Square (shown above), the State Richard E. Hart Recently, a relative of Ingmire in- House draped in mourning (shown on Photographs of Lincoln’s Springfield formed me that he had a number of the back), the Mather residence, and are rare. Newly discovered ones are photographs of Springfield taken by the entrance to Oak Ridge Cemetery in even rarer. Among the most familiar Ingmire in the 1860s. I thought that his May 1865. Two of these newly dis- of the known photographs are those photographs would be duplicates of the covered photographs are published in taken at the time of Lincoln’s funeral known funeral pictures. this issue and others will be published by Springfield photographer Frederick in future issues. I asked Springfield W. Ingmire—the Lincoln home and the When I received copies of the photo- historian Curtis Mann to write about Old State Capitol decorated in mourn- graphs, I was surprised to see new the photograph of the north side of the ing and Lincoln’s horse posed in front views of Lincoln’s Springfield, views I Public Square. His description follows of the Lincoln home. had never seen—the north side of the on the next page. -

Abraham Lincoln's Cooper Union Address

FF oo rr TT hh ee PP ee oo pp ll ee A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION VOLUME 16 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS WWW.ABRAHAMLINCOLNASSOCIATION.ORG Abraham Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address By Richard Brookhiser gines, are greater than anything that was available to Lincoln. Yet two of Lincoln’s mistakes are little known today—which sug- gests a narrowness of modern scholarship. The first half of the Cooper Union Address was a response to a speech by Stephen Douglas. Campaigning for a fellow Democ- rat in Ohio in September 1859, Douglas had said, “our fathers, when they framed the government under which we live, under- stood this question just as well, and even Richard Brookhiser is a biographer of the Found- better, than we do now.” “This question” ing Fathers (most recently author of James Madi- was whether the federal government could son, from Basic Books). His next book, also from restrict the expansion of slavery into the Basic, is Founders’ Son: A Life of Abraham Lin- territories. Douglas argued that federal con- coln, due out in October. It tells Lincoln’s story trol would violate the principle of self- as a lifelong engagement with the founders— government; each territory’s inhabitants Washington, Paine, Jefferson and their great — should decide for themselves whether to documents—the Declaration of Independence, the allow slavery or not. Lincoln at Cooper Un- Photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken in New Northwest Ordinance, the Constitution—and York City by Mathew Brady on February 27, shows how America’s greatest generation made ion agreed with Douglas that “our fathers” 1860, the day of Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address its greatest man. -

A NEW BIRTH of FREEDOM: STUDYING the LIFE of Lincolnabraham Lincoln at 200: a Bicentennial Survey

Civil War Book Review Spring 2009 Article 3 A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey Frank J. Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Williams, Frank J. (2009) "A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 11 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol11/iss2/3 Williams: A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Linco Feature Essay Spring 2009 Williams, Frank J. A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM: STUDYING THE LIFE OF LINCOLNAbraham Lincoln at 200: A Bicentennial Survey. No president has such a hold on our minds as Abraham Lincoln. He lived at the dawn of photography, and his pine cone face made a haunting picture. He was the best writer in all American politics, and his words are even more powerful than his images. His greatest trial, the Civil War, was the nation’s greatest trial, and the race problem that caused it is still with us today. His death by murder gave his life a poignant and violent climax, and allows us to play the always-fascinating game of “what if?" Abraham Lincoln did great things, greater than anything done by Theodore Roosevelt or Franklin Roosevelt. He freed the slaves and saved the Union, and because he saved the Union he was able to free the slaves. Beyond this, however, our extraordinary interest in him, and esteem for him, has to do with what he said and how he said it. -

The New York Times the Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Harold Holzer

[Pdf] The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds - download pdf free book The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 PDF, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 by Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds Download, Free Download The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Ebooks Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Full Collection, Free Download The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Full Popular Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds, by Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds pdf The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865, pdf Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865, the book The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865, Harold Holzer, President Bill Clinton, Craig Symonds ebook The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865, Download pdf The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865, Read Online The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Book, Read Online The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 E-Books, Read The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Book Free, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 PDF read online, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 pdf read online, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Ebooks Free, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 PDF Download, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Read Download, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Free PDF Download, The New York Times The Complete Civil War 1861-1865 Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE As mark berg m. -

Lincoln Seen and Heard'' February 11, 2005

Administration of George W. Bush, 2005 / Feb. 11 Remarks at the Performance of ‘‘Lincoln Seen and Heard’’ February 11, 2005 Thank you for that wonderful perform- for his work, and his latest book is, ‘‘Lin- ance. Laura and I welcome you all to the coln at Cooper Union.’’ White House. This evening I can let you all in on a I appreciate the members of my Cabinet secret. Tomorrow it will be announced that who are here and former members of the Allen Guelzo, who is with us tonight, and Cabinet who are here. I thank Senator Bill Harold Holzer are this year’s first and sec- Frist for joining us as well as Congressman ond place winners of the prestigious Lin- Mel Watt. Thank you both for coming. coln Prize. I appreciate Michael Steele, the Lieuten- Congratulations. ant Governor of the great State of Mary- Those of you who know Sam Waterston land, for joining us. I want to thank Bruce as ‘‘Jack McCoy’’ should know that Amer- Cole, the Chairman of the National Endow- ica’s most famous assistant district attorney ment for the Humanities. I appreciate has portrayed Abraham Lincoln on stage, Brian Lamb joining us today, the president on television, and so I’m told, even in bal- and CEO of C–SPAN. let. [Laughter] He didn’t dance. [Laughter] But he did narrate a special version of I thank the U.S. Lincoln Bicentennial Aaron Copland’s ‘‘Lincoln Portrait’’ while Commission members and the Advisory ballet dancers performed around him. Committee for joining us today. -

Rediscovering Civil War Classics:The Lincoln Nobody Knows

Civil War Book Review Spring 2005 Article 3 Rediscovering Civil War Classics:The Lincoln Nobody Knows Harold Holzer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Holzer, Harold (2005) "Rediscovering Civil War Classics:The Lincoln Nobody Knows," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol7/iss2/3 Holzer: Rediscovering Civil War Classics:The Lincoln Nobody Knows Feature Essay Holzer, Harold Spring 2005 Current, Richard N. REDISCOVERING CIVIL WAR CLASSICS:The Lincoln Nobody Knows. Greenwood Press Reprint, $82.50; (Availability: Out of Stock) ISBN 313224501 Lincoln for the ages 45 years old, and still current I will cheerfully admit to a long, highly personal, and undiminished attachment to a book called The Lincoln Nobody Knows (originally published by McGraw-Hill, 1958), along with an admiration that has grown into deep affection for its author, Richard Nelson Current. In writing about it, I could not begin to conceal my biases. Nor would I want to. How else to say it? The book changed my life. In fact, its presence in my hands and heart has unexpectedly, but wonderfully, bracketed my entire 40-plus years of experience in the Lincoln field: from my time as a grade school student searching for an interest, to the day just last spring when I was marking the publication of my own 23rd book, Lincoln at Cooper Union, and received a wonderful gift to cap the celebration--a special new copy of The Lincoln Nobody Knows. Thus when CWBR editor Frank Hardie asked me to fill David Madden's spot this issue with a guest column on my favorite classic book on the Civil War era, I did not hesitate in making my choice. -

Annual Report 2009

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Our Mission The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization supporting the study and love of American history through a wide range of programs and resources for students, teachers, scholars, and history enthusiasts throughout the nation. The Institute creates and works closely with history-focused schools; organizes summer seminars and development programs for teachers; produces print and digital publications and traveling exhibitions; hosts lectures by eminent historians; administers a History Teacher of the Year Award in every state and US territory; and offers national book prizes and fellowships for scholars to work in the Gilder Lehrman Collection as well as other renowned archives. Gilder Lehrman maintains two websites that serve as gateways to American history online with rich resources for educa - tors: www.gilderlehrman.org and the quarterly online journal www.historynow.org , designed specifically for K-12 teachers and students. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History Advisory Board Co-Chairmen President Executive Director Richard Gilder James G. Basker Lesley S. Herrmann Lewis E. Lehrman Joyce O. Appleby, Professor of History Emerita, Ellen V. Futter, President, American Museum University of California, Los Angeles of Natural History Edward L. Ayers, President, University of Richmond Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Alphonse Fletcher University William F. Baker, President Emeritus, Educational Professor and Director, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Broadcasting Corporation African and African American Research, Thomas H. Bender, University Professor of Harvard University the Humanities, New York University S. Parker Gilbert, Chairman Emeritus, Morgan Stanley Group Carol Berkin, Presidential Professor of History, Allen C. Guelzo, Henry R. -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Fall 2019/Winter 2020 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Listen, my children, and you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere Dear Friends, Who among us has not been enthralled by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s description of Revolutionary War hero Paul Revere’s famous ride? This fall, New-York Historical reveals the true story Buck Ennis, Crain’s New York Business of the patriot, silversmith, and entrepreneur immortalized in the Longfellow poem in a brand new, family-friendly exhibition organized by the American Antiquarian Society. It’s a great opportunity for multi-generational visitors, but interesting, intriguing, and provocative for anyone interested in history and art—which surely includes you! Related programming featuring New-York Historical Trustee Annette Gordon- Reed and distinguished constitutional scholar Philip Bobbitt is on offer through our Bernard and Irene Schwartz Distinguished Speakers Series. Less well-known is the story of Mark Twain and the Holy Land, told in a new exhibition on view this season in our Pam and Scott Schafler Gallery. Jonathan Sarna and Gil Troy reflect on the topic in what is sure to be a fascinating Schwartz Series program presented in partnership with the Shapell Manuscript Foundation. Other Schwartz Series programs include “An Evening with Neal Katyal” moderated by New-York Historical Trustee Akhil Reed Amar; “Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know about the People We Don’t Know” featuring Malcolm Gladwell in conversation with Adam Gopnik; and “An Evening with George Will: The Conservative Sensibility” moderated by Richard Brookhiser. -

The Presidents Vs. the Press Professor Harold Holzer

The Presidents vs. The Press Professor Harold Holzer Spring 2021 Course Description The tension between presidents and journalists is as old as the republic itself. George Washington, upon seeing an unflattering caricature of himself in a local newspaper “got into one of those passions when he cannot command himself,” according to then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Since the founding era, almost everything about access and expectation, literacy and technology has changed. At the same time, the office of the president has grown increasingly powerful. This course chronicles the eternal battle between the core institutions that define the republic, revealing that the essence of this confrontation is built into the fabric of the nation. Course Readings 1. Buhite, Russell D., and David W. Levy, eds. FDR’s Fireside Chats. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992. 2. Holzer, Harold. Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014. 3. Holzer, Harold. The Presidents vs. the Press: The Endless Battle between the White House and the Media—From the Founding Fathers to Fake News. New York: E.P. Dutton, 2020. 4. Mock, James R., and Cedric Larson. Words That Won the War: The Story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917–1919. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1939. 5. Woodward, Bob, and Carl Bernstein. All the President’s Men: The Greatest Reporting Story of All Time. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012. Course Requirements ● Contribute to nine discussion boards ● Complete five short papers (1–2 pages) ● Participate in at least three Q&As ● Complete a 15-page research paper or project of appropriate rigor Class Schedule Week 1: February 4: “Malignant Industry”: George Washington Readings ● Holzer, The Presidents vs.