Full Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abraham Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is one of the most quoted speeches in American history. The text is brief, just three paragraphs amounting to less than 300 words. It only took Lincoln a few minutes to read it, but his words resonate to the present day. It’s unclear how much time Lincoln spent writing the speech, but analysis by scholars over the years indicates that Lincoln used extreme care. It was a heartfelt and precise message he very much wanted to deliver at a moment of national crisis. The dedication of a cemetery at the site of the Civil War's most pivotal battle was a solemn event. And when Lincoln was invited to speak, he recognized that the moment required him to make a major statement. Lincoln Intended a Major Statement The Battle of Gettysburg had taken place in rural Pennsylvania for the first three days of July in 1863. Thousands of men, both Union and Confederate, had been killed. The magnitude of the battle stunned the nation. As the summer of 1863 turned into fall, the Civil War entered a fairly slow period with no major battles being fought. Lincoln, very concerned that the nation was growing weary of a long and very costly war, was thinking of making a public statement affirming the country’s need to continue fighting. Immediately following the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July, Lincoln had said the occasion called for a speech but he was not yet prepared to give one equal to the occasion. -

'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech'

H-FedHist White on Conant, 'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech' Review published on Monday, September 18, 2017 Sean Conant, ed. The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. xvi + 350 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-19-022745-6; $79.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-022744-9. Reviewed by Jonathan W. White (Christopher Newport University)Published on H-FedHist (September, 2017) Commissioned by Caryn E. Neumann When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton read the Gettysburg Address to a Republican rally in Pennsylvania in 1868, he declared triumphantly, “That is the voice of God speaking through the lips of Abraham Lincoln!”[1] Indeed, the speech has become akin to American scripture. This collection of essays, now available in paperback, was originally put together to accompany a film titledThe Gettysburg Address (2017), which was produced by the editor of this book, Sean Conant. It brings “a new birth of fresh analysis for those who still love those words and still yearn to better understand them,” writes Harold Holzer in the foreword (p. xv). The volume is broken up into two parts: “Influences” and “Impacts,” with chapters from a number of notable Lincoln scholars and Civil War historians. The opening essay, by Nicholas P. Cole, challenges Garry Wills’s interpretation of the address, offering the sensible observation that “rather than setting Lincoln’s words in the context of Athenian funeral oratory, it is perhaps more natural to explain both the form of Lincoln’s words and their popular reception at the time in the context of the Fourth of July orations that would have been immediately familiar to both Lincoln and his audience” (p. -

The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900

This is a repository copy of The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/132794/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2017) The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900. In: Watt, P, Scott, DB and Spedding, P, (eds.) Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century: A Cultural History of the Songster. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge, UK , pp. 73-90. ISBN 9781107159914 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316672037.005 © 2017, Paul Watt, Derek B. Scott and Patrick Spedding. This material has been published in Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century: A Cultural History of the Songster edited by P. Watt, D. Scott, & P. Spedding. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

The Presidents of Mount Rushmore

The PReSIDeNTS of MoUNT RUShMoRe A One Act Play By Gloria L. Emmerich CAST: MALE: FEMALE: CODY (student or young adult) TAYLOR (student or young adult) BRYAN (student or young adult) JESSIE (student or young adult) GEORGE WASHINGTON MARTHA JEFFERSON (Thomas’ wife) THOMAS JEFFERSON EDITH ROOSEVELT (Teddy’s wife) ABRAHAM LINCOLN THEODORE “TEDDY” ROOSEVELT PLACE: Mount Rushmore National Memorial Park in Keystone, SD TIME: Modern day Copyright © 2015 by Gloria L. Emmerich Published by Emmerich Publications, Inc., Edenton, NC. No portion of this dramatic work may be reproduced by any means without specific permission in writing from the publisher. ACT I Sc 1: High school students BRYAN, CODY, TAYLOR, and JESSIE have been studying the four presidents of Mount Rushmore in their history class. They decided to take a trip to Keystone, SD to visit the national memorial and see up close the faces of the four most influential presidents in American history. Trying their best to follow the map’s directions, they end up lost…somewhere near the face of Mount Rushmore. All four of them are losing their patience. BRYAN: We passed this same rock a half hour ago! TAYLOR: (Groans.) Remind me again whose idea it was to come here…? CODY: Be quiet, Taylor! You know very well that we ALL agreed to come here this summer. We wanted to learn more about the presidents of Mt. Rushmore. BRYAN: Couldn’t we just Google it…? JESSIE: Knock it off, Bryan. Cody’s right. We all wanted to come here. Reading about a place like this isn’t the same as actually going there. -

Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Allen C

Civil War Era Studies Faculty Publications Civil War Era Studies 2014 "Public Sentiment Is Everything": Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Allen C. Guelzo Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac Part of the Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Guelzo, Allen C. "'Public Sentiment Is Everything': Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion." Lincoln and Liberty: Wisdom for the Ages Ed. Lucas E. Morel (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 171-190. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac/56 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Public Sentiment Is Everything": Abraham Lincoln and the Power of Public Opinion Abstract Book Summary: Since Abraham Lincoln’s death, generations of Americans have studied his life, presidency, and leadership, often remaking him into a figure suited to the needs and interests of their own time. This illuminating volume takes a different approach to his political thought and practice. Here, a distinguished group of contributors argue that Lincoln’s relevance today is best expressed by rendering an accurate portrait of him in his own era. They es ek to understand Lincoln as he understood himself and as he attempted to make his ideas clear to his contemporaries. -

Lincoln and Emancipation: a Man's Dialogue with His Times

DOCUMRNT flitSUP48 ED 032 336 24 TE 499 934 By -Minear, Lawrence Lincoln and Emancipation: A Man's Dialogue with His Times. Teacher and Student Manuals. Amherst Coll., Mass. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DREW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Report No -CRP -H 1 68 Bureau No-BR-S-1071 Pub Date 66 Contract -OEC 5-10-158 Note-137p. EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors -*Civil War (United States),*Curriculum Guides, Democracy, Government Role, *Leadership Qualities, Leadership Styles, Political Influences, Political Issues, Political Power, Role Conflict, Secondary Education, Self Concept. *Slavery. *Social Studies. United States History Identifiers -*Abraham Lincoln. Emancipation Proclamation Focusing on Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation of the Negro, this social studies unit explores the relationships among men and events, the qualities of leadership. and the nature of historical change. Lincoln's evolving views of the Negro are examined through (1) the historical context in which Lincoln's beliefs about Negroes took shape, (2) the developments in Lincoln's political life, from 1832 through 1861, which affected his beliefs about Negroes, (3) the various military, political.. and diplomatic pressures exerted on Lincoln as President which made him either the captive or master of events, (4) the two Emancipation Proclamations and the relationship between principle and expediency, (5) the impact of the emancipation on Lincoln's understanding of the conduct and purposes of the war and the conditions of peace, and (6) Lincoln's views on reconstruction in relation to emancipation, Inlcuded are suggestions for further reading, maps. charts. and writings from the period which elucidate Lincoln's political milieu. -

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Address of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society NAID 306639 From 1830 on, women organized politically to reform American society. The leading moral cause was abolishing slavery. “Sisters and Friends: As immortal souls, created by God to know and love him with all our hearts, and our neighbor as ourselves, we owe immediate obedience to his commands respecting the sinful system of Slavery, beneath which 2,500,000 of our Fellow-Immortals, children of the same country, are crushed, soul and body, in the extremity of degradation and agony.” July 13, 1836 The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1832 as a female auxiliary to male abolition societies. The society created elaborate networks to print, distribute, and mail petitions against slavery. In conjunction with other female societies in major northern cities, they brought women to the forefront of politics. In 1836, an estimated 33,000 New England women signed petitions against the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The society declared this campaign an enormous success and vowed to leave, “no energy unemployed, no righteous means untried” in their ongoing fight to abolish slavery. www.archives.gov/legislative/resources Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sanford NAID 301674 In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that Americans of African ancestry had no constitutional rights. “The question is simply this: Can a Negro whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such, become entitled to all the rights and privileges and immunities guaranteed to the citizen?.. -

The Lincoln Assassination: Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory

LincolnThe Assassination CRIME&PUNISHMENT, MYTH& MEMORY edited by HAROLD HOLZER, CRAIG L. SYMONDS & FRANK J. WILLIAMS A LINCOLN FORUM BOOK The Lincoln Assassination ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:09:42 PS PAGE i ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:36 PS PAGE ii T he L incoln Forum The Lincoln Assassination Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York • 2010 ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:37 PS PAGE iii Frontispiece: A. Bancroft, after a photograph by the Mathew Brady Gallery, To the Memory of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States . Lithograph, published in Philadelphia, 1865. (Indianapolis Museum of Art, Mary B. Milliken Fund) Copyright ᭧ 2010 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Lincoln assassination : crime and punishment, myth and memory / edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams.—1st ed. p. cm.— (The North’s Civil War) ‘‘The Lincoln Forum.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8232-3226-0 (cloth : alk. -

Chapter 11: the Civil War, 1861-1865

The Civil War 1861–1865 Why It Matters The Civil War was a milestone in American history. The four-year-long struggle determined the nation’s future. With the North’s victory, slavery was abolished. During the war, the Northern economy grew stronger, while the Southern economy stagnated. Military innovations, including the expanded use of railroads and the telegraph, coupled with a general conscription, made the Civil War the first “modern” war. The Impact Today The outcome of this bloody war permanently changed the nation. • The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. • The power of the federal government was strengthened. The American Vision Video The Chapter 11 video, “Lincoln and the Civil War,” describes the hardships and struggles that Abraham Lincoln experienced as he led the nation in this time of crisis. 1862 • Confederate loss at Battle of Antietam 1861 halts Lee’s first invasion of the North • Fort Sumter fired upon 1863 • First Battle of Bull Run • Lincoln presents Emancipation Proclamation 1859 • Battle of Gettysburg • John Brown leads raid on federal ▲ arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia Lincoln ▲ 1861–1865 ▲ ▲ 1859 1861 1863 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1861 1862 1863 • Russian serfs • Source of the Nile River • French troops 1859 emancipated by confirmed by John Hanning occupy Mexico • Work on the Suez Czar Alexander II Speke and James A. Grant City Canal begins in Egypt 348 Charge by Don Troiani, 1990, depicts the advance of the Eighth Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Battle of Chancellorsville. 1865 • Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse • Abraham Lincoln assassinated by John Wilkes Booth 1864 • Fall of Atlanta HISTORY • Sherman marches ▲ A. -

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor. -

The Life of Abraham Lincoln

Mr. Lincoln: The Life of Abraham Lincoln Professor Allen C. Guelzo THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Allen C. Guelzo, Ph.D. Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of Civil War Era Studies, Gettysburg College Dr. Allen C. Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of Civil War Era Studies at Gettysburg College in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He is also the Associate Director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. He was born in Yokohama, Japan, but grew up in Philadelphia. He holds an M.A. and Ph.D. in history from the University of Pennsylvania, where he wrote his dissertation under the direction of Bruce Kuklick, Alan C. Kors, and Richard S. Dunn. Dr. Guelzo has taught at Drexel University and, for 13 years, at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania. At Eastern, he was the Grace Ferguson Kea Professor of American History, and from 1998 to 2004, he was the founding dean of the Templeton Honors College at Eastern. Dr. Guelzo is the author of numerous books on American intellectual history and on Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War era, beginning with his first work, Edwards on the Will: A Century of American Theological Debate, 1750– 1850 (Wesleyan University Press, 1989). His second book, For the Union of Evangelical Christendom: The Irony of the Reformed Episcopalians, 1873–1930 (Penn State University Press, 1994), won the Outler Prize for Ecumenical Church History of the American Society of Church History. He wrote The Crisis of the American Republic: A History of the Civil War and Reconstruction for the St. -

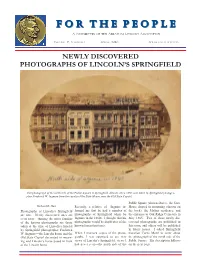

F O R T H E P E O P

FF oo rr TT hh ee PP ee oo pp ll ee A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1 SPRING 2010 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS NEWLY DISCOVERED PHOTOGRAPHS OF LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD This photograph of the north side of the Public Square in Springfield, Illinois, circa 1860, was taken by Springfield photogra- pher Frederick W. Ingmire from the cupola of the State House, now the Old State Capitol. Public Square (shown above), the State Richard E. Hart Recently, a relative of Ingmire in- House draped in mourning (shown on Photographs of Lincoln’s Springfield formed me that he had a number of the back), the Mather residence, and are rare. Newly discovered ones are photographs of Springfield taken by the entrance to Oak Ridge Cemetery in even rarer. Among the most familiar Ingmire in the 1860s. I thought that his May 1865. Two of these newly dis- of the known photographs are those photographs would be duplicates of the covered photographs are published in taken at the time of Lincoln’s funeral known funeral pictures. this issue and others will be published by Springfield photographer Frederick in future issues. I asked Springfield W. Ingmire—the Lincoln home and the When I received copies of the photo- historian Curtis Mann to write about Old State Capitol decorated in mourn- graphs, I was surprised to see new the photograph of the north side of the ing and Lincoln’s horse posed in front views of Lincoln’s Springfield, views I Public Square. His description follows of the Lincoln home. had never seen—the north side of the on the next page.