The New Gettysburg Address: Fusing History and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech'

H-FedHist White on Conant, 'The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech' Review published on Monday, September 18, 2017 Sean Conant, ed. The Gettysburg Address: Perspectives on Lincoln's Greatest Speech. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. xvi + 350 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-19-022745-6; $79.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-19-022744-9. Reviewed by Jonathan W. White (Christopher Newport University)Published on H-FedHist (September, 2017) Commissioned by Caryn E. Neumann When Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton read the Gettysburg Address to a Republican rally in Pennsylvania in 1868, he declared triumphantly, “That is the voice of God speaking through the lips of Abraham Lincoln!”[1] Indeed, the speech has become akin to American scripture. This collection of essays, now available in paperback, was originally put together to accompany a film titledThe Gettysburg Address (2017), which was produced by the editor of this book, Sean Conant. It brings “a new birth of fresh analysis for those who still love those words and still yearn to better understand them,” writes Harold Holzer in the foreword (p. xv). The volume is broken up into two parts: “Influences” and “Impacts,” with chapters from a number of notable Lincoln scholars and Civil War historians. The opening essay, by Nicholas P. Cole, challenges Garry Wills’s interpretation of the address, offering the sensible observation that “rather than setting Lincoln’s words in the context of Athenian funeral oratory, it is perhaps more natural to explain both the form of Lincoln’s words and their popular reception at the time in the context of the Fourth of July orations that would have been immediately familiar to both Lincoln and his audience” (p. -

The Rhetoric of Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address

1 The Rhetoric of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Why It Works the Way It Works George D. Gopen Professor Emeritus of the Practice of Rhetoric Duke University Copyright, 2019: George D. Gopen 2 The Rhetoric of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: Why It Works the Way It Works The Gettysburg Address Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us--that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion--that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth. -

The Lincoln Assassination: Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory

LincolnThe Assassination CRIME&PUNISHMENT, MYTH& MEMORY edited by HAROLD HOLZER, CRAIG L. SYMONDS & FRANK J. WILLIAMS A LINCOLN FORUM BOOK The Lincoln Assassination ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:09:42 PS PAGE i ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:36 PS PAGE ii T he L incoln Forum The Lincoln Assassination Crime and Punishment, Myth and Memory edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York • 2010 ................. 17679$ $$FM 03-25-10 09:11:37 PS PAGE iii Frontispiece: A. Bancroft, after a photograph by the Mathew Brady Gallery, To the Memory of Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States . Lithograph, published in Philadelphia, 1865. (Indianapolis Museum of Art, Mary B. Milliken Fund) Copyright ᭧ 2010 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Lincoln assassination : crime and punishment, myth and memory / edited by Harold Holzer, Craig L. Symonds, and Frank J. Williams.—1st ed. p. cm.— (The North’s Civil War) ‘‘The Lincoln Forum.’’ Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8232-3226-0 (cloth : alk. -

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor. -

Abraham Lincolm Was Born On

Abraham Lincoln and Marshall, IL By Brian Burger, Andy Sweitzer, David Tingley Abraham Lincoln was born on Feb. 12, 1809 in Hodgenville, Kentucky. Abraham's parents were Nancy Hanks and Thomas Lincoln. At the age of two he was taken by his parents to nearby Knob Creek and at eight to Spencer County, Indiana. The following year his mother died. In 1819, his father married Sarah Bush Johnston. In 1831, after moving with his family to Macon County, Illinois, he struck out on his own, taking cargo on a flatboat to New Orleans, Louisiana. He then returned to Illinois and settled in New Salem where he split rails and clerked in a store. In 1833, he was appointed postmaster but had to supplement his income with surveying and various other jobs. At the same time he began to study law. In 1832, Lincoln ran for state legislature. He was defeated, but he won two years later and served in the Lower House from 1834 to 1841. He quickly emerged as a leader of the Whig Party and was involved in the moving of the capital to Springfield. In 1836, Lincoln was admitted to the bar. He then entered successful partnerships with John T. Stuart, Stephen T. Logan, and William Herndon. Based on this success, Lincoln soon won recognition as an effective and resourceful attorney. Even though Lincoln was born in Kentucky, a slave state, he had long opposed slavery. In the state legislature, he had voted against the "peculiar institution" and in 1837 was one of only two members to protest it. -

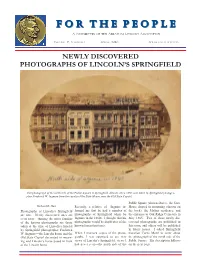

F O R T H E P E O P

FF oo rr TT hh ee PP ee oo pp ll ee A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1 SPRING 2010 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS NEWLY DISCOVERED PHOTOGRAPHS OF LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD This photograph of the north side of the Public Square in Springfield, Illinois, circa 1860, was taken by Springfield photogra- pher Frederick W. Ingmire from the cupola of the State House, now the Old State Capitol. Public Square (shown above), the State Richard E. Hart Recently, a relative of Ingmire in- House draped in mourning (shown on Photographs of Lincoln’s Springfield formed me that he had a number of the back), the Mather residence, and are rare. Newly discovered ones are photographs of Springfield taken by the entrance to Oak Ridge Cemetery in even rarer. Among the most familiar Ingmire in the 1860s. I thought that his May 1865. Two of these newly dis- of the known photographs are those photographs would be duplicates of the covered photographs are published in taken at the time of Lincoln’s funeral known funeral pictures. this issue and others will be published by Springfield photographer Frederick in future issues. I asked Springfield W. Ingmire—the Lincoln home and the When I received copies of the photo- historian Curtis Mann to write about Old State Capitol decorated in mourn- graphs, I was surprised to see new the photograph of the north side of the ing and Lincoln’s horse posed in front views of Lincoln’s Springfield, views I Public Square. His description follows of the Lincoln home. had never seen—the north side of the on the next page. -

Lincoln's New Salem, Reconstructed

Lincoln’s New Salem, Reconstructed MARK B. POHLAD “Not a building, scarcely a stone” In his classic Lincoln’s New Salem (1934), Benjamin P. Thomas observed bluntly, “By 1840 New Salem had ceased to exist.”1 A century later, however, a restored New Salem was—after the Lincoln Memorial, in Washington, D.C.—the most visited Lincoln site in the world. How this transformation occurred is a fascinating story, one that should be retold, especially now, when action must be taken to rescue the present New Salem from a grave decline. Even apart from its connection to Abraham Lincoln, New Salem is like no other reconstructed pioneer village that exists today. Years before the present restoration occurred, planners aimed for a unique destination. A 1920s state-of- Illinois brochure claimed that once the twenty- five original structures were rebuilt on their original founda- tions, it would be “the only known city in the world that has ever been restored in its entirety.”2 In truth, it is today the world’s largest log- house village reconstructed on its original site and on its build- ings’ original foundations. It is still startling nearly two hundred years later that a town of more than a hundred souls—about the same number as lived in Chicago at that time—existed for only a decade. But such was the velocity of development in the American West. “Petersburg . took the wind out of its sails,” a newspaperman quipped in 1884, because a new county seat and post office had been established there; Lincoln himself had surveyed it.3 Now the very buildings of his New Salem friends and 1. -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

Abraham Lincoln's Cooper Union Address

FF oo rr TT hh ee PP ee oo pp ll ee A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION VOLUME 16 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS WWW.ABRAHAMLINCOLNASSOCIATION.ORG Abraham Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address By Richard Brookhiser gines, are greater than anything that was available to Lincoln. Yet two of Lincoln’s mistakes are little known today—which sug- gests a narrowness of modern scholarship. The first half of the Cooper Union Address was a response to a speech by Stephen Douglas. Campaigning for a fellow Democ- rat in Ohio in September 1859, Douglas had said, “our fathers, when they framed the government under which we live, under- stood this question just as well, and even Richard Brookhiser is a biographer of the Found- better, than we do now.” “This question” ing Fathers (most recently author of James Madi- was whether the federal government could son, from Basic Books). His next book, also from restrict the expansion of slavery into the Basic, is Founders’ Son: A Life of Abraham Lin- territories. Douglas argued that federal con- coln, due out in October. It tells Lincoln’s story trol would violate the principle of self- as a lifelong engagement with the founders— government; each territory’s inhabitants Washington, Paine, Jefferson and their great — should decide for themselves whether to documents—the Declaration of Independence, the allow slavery or not. Lincoln at Cooper Un- Photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken in New Northwest Ordinance, the Constitution—and York City by Mathew Brady on February 27, shows how America’s greatest generation made ion agreed with Douglas that “our fathers” 1860, the day of Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address its greatest man. -

Bulletin 86 - the Lincoln-Douglas Debate S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Eastern Illinois University Bulletin University Publications 10-1-1924 Bulletin 86 - The Lincoln-Douglas Debate S. E. Thomas Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/eiu_bulletin Recommended Citation Thomas, S. E., "Bulletin 86 - The Lincoln-Douglas Debate" (1924). Eastern Illinois University Bulletin. 183. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/eiu_bulletin/183 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Illinois University Bulletin by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , liBRARY : ~TERN ILLINOIS STAtE CO~ CHARLESTON, ILLINOI$ ; ,' JB The EXH Teachers College Bulletin Number 86 October 1, 1924 Eastern Illinois State Teachers College ~ -AT- CHARLESTON Lincoln-Douglas Debate A narrative and descriptive account of the events of the day of the debate in Charleston -By- S. E. THOMAS PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, EASTERN ILLINOIS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE PUBLISHERS EXHIBIT _ The Teachers College Bulletin Published Quarterly by the Eastern Illinois State Teachers College at Charleston Entered March 5, 1902, as second-class matter, at the post office at Charles ton, Illinois. Act of Congress, July 16, 1894. No. 86 CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS October 1, 1924 Lincoln-Douglas Debate The fourth joint debate between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, held in Charleston, Coles County, Ill inois, on September the eight- eenth, eighteen hundred and fifty-eight A narrative and descriptive account of the events of the day of the debate in Charleston -By- S. E. THOMAS PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, EASTERN ILLINOIS STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE [Printe d by authority of the State of Illinois] (59521-2M-11-26) ~2 FOREWORD This paper was read at the semi-centennial celebration of the Lincoln Dcuglas Detate in Charleston, Illinois, September 18, 1908. -

CONSUMING LINCOLN: ABRAHAM LINCOLN's WESTERN MANHOOD in the URBAN NORTHEAST, 1848-1861 a Dissertation Submitted to the Kent S

CONSUMING LINCOLN: ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WESTERN MANHOOD IN THE URBAN NORTHEAST, 1848-1861 A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By David Demaree August 2018 © Copyright All right reserved Except for previously published materials A dissertation written by David Demaree B.A., Geneva College, 2008 M.A., Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2012 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2018 Approved by ____________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kevin Adams, Ph.D. ____________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Elaine Frantz, Ph.D. ____________________________, Lesley J. Gordon, Ph.D. ____________________________, Sara Hume, Ph.D. ____________________________ Robert W. Trogdon, Ph.D. Accepted by ____________________________, Chair, Department of History Brian M. Hayashi, Ph.D. ____________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences James L. Blank, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS...............................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 -

Lincoln S New Salem State Historic Site Invites You & Your Family to The

Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site Welcomes You Lincoln s New Salem State Historic Site invites you & your family to the Reunion of Direct Descendants of the New Salem Community Saturday, July 8, 2006 Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site Petersburg, Illinois The 2006 Lincoln’s Landing events celebrate the 175th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s arrival at New Salem July 8, 2006, is the Reunion of Direct Descendants of New Salem. Direct descendants will be recognized as special guests of New Salem and the Illinois Historical Preservation Agency. Descendants, relatives, friends, and visitors are invited to enjoy many special activities. Some descendant families have scheduled reunions in the area this weekend, and many participants are coming great distances to attend. We are happy to welcome everyone to New Salem. Please check in with us at the Descendant’s Registration Desk at the Visitors Center. Enjoy meeting new relatives and sharing your family history with family, friends, and the site. The contact for this event is Event Chair Barbara Archer, who may be reached at 217- 546-4809 or [email protected] for further information and details. To reach New Salem from Springfield, follow Route 125 (Jefferson Street) to Route 97 (about 12 miles west), turn right at the brown New Salem sign; travel 12 miles to the site entrance. From Chicago, exit Interstate 55 at the Williamsville Exit 109 and follow the signs or take the Springfield Clear Lake Exit 98; Clear Lake becomes Route 125. From St. Louis, take 55 Exit 92 to Route 72 west; exit 72 at Route 4/Veterans Parkway Exit 93; take Veterans Parkway north to Route 125; turn left.