Early Life-History of Melampus and the Significance of Semilunar Synchrony'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Freeze Tolerance in a Historically Tropical Snail Alice B

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 The evolution of freeze tolerance in a historically tropical snail Alice B. Dennis Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Dennis, Alice B., "The ve olution of freeze tolerance in a historically tropical snail" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1003. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1003 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF FREEZE TOLERANCE IN A HISTORICALLY TROPICAL SNAIL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Alice B. Dennis B.S., University of California, Davis 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have helped make this dissertation possible. I would first like to thank my advisor, Michael E. Hellberg, for his support and guidance. Comments and discussion with my committee: Drs. Sibel Bargu Ates, Robb T. Brumfield, Kenneth M. Brown, and William B. Stickle, have been very helpful throughout the development of this project. I would also like to thank those whose guidance helped lead me down this path, particularly Rick Grosberg, John P. Wares and Alex C. C. Wilson. -

Bab Iv Hasil Penelitian Dan Pembahasan

BAB IV HASIL PENELITIAN DAN PEMBAHASAN A. Hasil Penelitian dan Pembahasan Tahap 1 1. Kondisi Faktor Abiotik Ekosistem perairan dapat dipengaruhi oleh suatu kesatuan faktor lingkungan, yaitu biotik dan abiotik. Faktor abiotik merupakan faktor alam non-organisme yang mempengaruhi proses perkembangan dan pertumbuhan makhluk hidup. Dalam penelitian ini, dilakukan analisis faktor abiotik berupa faktor kimia dan fisika. Faktor kimia meliputi derajat keasaman (pH). Sedangkan faktor fisika meliputi suhu dan salinitas air laut. Hasil pengukuran suhu, salinitas, dan pH dapat dilihat sebagai tabel berikut: Tabel 4.1 Faktor Abiotik Pantai Peh Pulo Kabupaten Blitar Faktor Abiotik No. Letak Substrat Suhu Salinitas Ph P1 29,8 20 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir S1 1. P2 30,1 23 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 30,5 28 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 2. P1 29,7 38 8 Berbatu dan Berpasir S2 P2 29,7 40 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 29,7 33 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 3. P1 30,9 41 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir S3 P2 30,3 42 8 Berbatu dan Berpasir P3 30,1 41 7 Berbatu dan Berpasir 77 78 Tabel 4.2 Rentang Nilai Faktor Abiotik Pantai Peh Pulo Faktor Abiotik Nilai Suhu (˚C) 29,7-30,9 Salinitas (%) 20-42 Ph 7-8 Berdasarkan pengukuran faktor abiotik lingkungan, masing-masing stasiun pengambilan data memiliki nilai yang berbeda. Hal ini juga mempengaruhi kehidupan gastropoda yang ditemukan. Kehidupan gastropoda sangat dipengaruhi oleh besarnya nilai suhu. Suhu normal untuk kehidupan gastropoda adalah 26-32˚C.80 Sedangkan menurut Sutikno, suhu sangat mempengaruhi proses metabolisme suatu organisme, gastropoda dapat melakukan proses metabolisme optimal pada kisaran suhu antara 25- 32˚C. -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

24 Relationships Within the Ellobiidae

Origin atld evoltctiorzai-y radiatiotz of the Mollrisca (ed. J. Taylor) pp. 285-294, Oxford University Press. O The Malacological Sociery of London 1996 R. Clarke. 24 paleozoic .ine sna~ls. RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN THE ELLOBIIDAE ANTONIO M. DE FRIAS MARTINS Departamento de Biologia, Universidade dos Aqores, P-9502 Porzta Delgada, S6o Miguel, Agores, Portugal ssification , MusCum r Curie. INTRODUCTION complex, and an assessment is made of its relevance in :eny and phylogenetic relationships. 'ulmonata: The Ellobiidae are a group of primitive pulmonate gastropods, Although not treated in this paper, conchological features (apertural dentition, inner whorl resorption and protoconch) . in press. predominantly tropical. Mostly halophilic, they live above the 28s rRNA high-tide mark on mangrove regions, salt-marshes and rolled- and radular morphology were studied also and reference to ~t limpets stone shores. One subfamily, the Carychiinae, is terrestrial, them will be made in the Discussion. inhabiting the forest leaf-litter on mountains throughout ago1 from the world. MATERIAL AND METHODS 'finities of The Ellobiidae were elevated to family rank by Lamarck (1809) under the vernacular name "Les AuriculacCes", The anatomy of 35 species representing 19 genera was ~Ctiquedu properly latinized to Auriculidae by Gray (1840). Odhner studied (Table 24.1). )llusques). (1925), in a revision of the systematics of the family, preferred For the most part the animals were immersed directly in sciences, H. and A. Adarns' name Ellobiidae (in Pfeiffer, 1854). which 70% ethanol. Some were relaxed overnight in isotonic MgCl, ochemical has been in general use since that time. and then preserved in 70% ethanol. A reduced number of Grouping of the increasingly growing number of genera in specimens of most species was fixed in Bouin's, serially Gebriider the family was based mostly on conchological characters. -

The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography

ISSN 1031-8062 ISBN 0 7305 5592 5 The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography K. A. Rodgers and Carol' Cant.-11 Technical Reports of the Australian Museu~ Number-t TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Technical Reports of the Australian Museum is D.J.G . Griffin a series of occasional papers which publishes Editor: bibliographies, catalogues, surveys, and data bases in J.K. Lowry the fields of anthropology, geology and zoology. The journal is an adjunct to Records of the Australian Assistant Editor: J.E. Hanley Museum and the Supplement series which publish original research in natural history. It is designed for Associate Editors: the quick dissemination of information at a moderate Anthropology: cost. The information is relevant to Australia, the R.J. Lampert South-west Pacific and the Indian Ocean area. Invertebrates: Submitted manuscripts are reviewed by external W.B. Rudman referees. A reasonable number of copies are distributed to scholarly institutions in Australia and Geology: around the world. F.L. Sutherland Submitted manuscripts should be addressed to the Vertebrates: Editor, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney A.E . Greer South, N.S.W. 2000, Australia. Manuscripts should preferably be on 51;4 inch diskettes in DOS format and ©Copyright Australian Museum, 1988 should include an original and two copies. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the Editor. Technical Reports are not available through subscription. New issues will be announced in the Produced by the Australian Museum Records. Orders should be addressed to the Assistant 15 September 1988 Editor (Community Relations), Australian Museum, $16.00 bought at the Australian Museum P.O. -

Patterns of Mollusc Distribution in Mangroves from the São Marcos Bay, Coast of Maranhão State, Brazil

ACTA AMAZONICA http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4392201600493 Patterns of mollusc distribution in mangroves from the São Marcos Bay, coast of Maranhão State, Brazil Carlos A. L. RODRIGUES1, Rannyele P. RIBEIRO1,2,*, Nayara B. SANTOS1; Zafira S. ALMEIDA1 1Universidade Estadual do Maranhão, Departamento de Química e Biologia, Avenida Lourenço Vieira da Silva, S/N, Tirirical, São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil. 2 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Núcleo em Ecologia e Desenvolvimento Sócio-ambiental de Macaé. Avenida São José do Barreto 764, São José do Barreto, Macaé, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. * Correspondig author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The diversity and distribution of molluscs from the Amazon Coast of Maranhão State, Brazil, are poorly understood. The aim of this study was to investigate how molluscs in two mangrove creeks (Buenos Aires and Tronco) at the São Marcos Bay, coast of the Maranhão State, respond to spatial and temporal variations in the environment. Sampling was performed in the intertidal area along three zones established using a straight line transect of 100 m. Abiotic variables of water and sediment were measured at each creek. We found 5,912 specimens belonging to 23 species and 15 families of epifaunal and infaunal molluscs. The patterns of their distribution in the two creeks were different. Salinity, dissolved oxygen, and rainfall were the main variables that affected the temporal distribution of molluscs. We found low species richness in the overall mollusc composition. Diversity in the Buenos Aires Creek was lower than that observed in the Tronco Creek, possibly because of activities of a port located in proximity to the former. -

Rumahlatu D., Leiwakabessy F., 2017 Biodiversity of Gastropoda in the Coastal Waters of Ambon Island, Indonesia

Biodiversity of gastropoda in the coastal waters of Ambon Island, Indonesia Dominggus Rumahlatu, Fredy Leiwakabessy Biology Education Study Program, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education Science, Pattimura University, Ambon, Indonesia. Corresponding author: D. Rumahlatu, [email protected] Abstract. Gastropods belonging to the mollusk phylum are widespread in various ecosystems. Ecologically, the spread of gastropoda is influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature, salinity, pH and dissolved oxygen. This research was conducted to determine the correlation between the factors of physico-chemical environment and the diversity of gastropoda in coastal water of Ambon Island, Indonesia. This research was conducted at two research stations, namely Station 1 at Ujung Tanjung Latuhalat Beach and Station 2 at coastal water of Waitatiri Passo. The results of a survey revealed that the average temperature on station 1 was 31.14°C while the average temperature of ° station 2 was 29.90 C. The average salinity at Station 1 was 32.02%o whereas the salinity average at Station 2 was 30.31%o. The average pH in station 1 and 2 was 7.03, while the dissolved oxygen at station 1 was 7.68 ppm which was not far different from that in station 2 with the dissolved oxygen of 7.63 ppm. The total number of species found in both research stations was 65 species, with the types of gastropoda were found scattered in 48 genera, 19 families and 7 orders. The most commonly found gastropods were from the genus of Nerita and Conus. 40 species were found in station 1 and 40 species were found in station 2. -

Pedipedinae (Gastropoda: Ellobiidae) from Hong Kong

The marine flora and fauna of Hong Kong and southern China III (ed. B. Morton). Proceedings of the Fourth International Marine Biological Workshop: The Marine Flora and Fauna of Hong Kong and Southern China, Hong Kong, 11-29 April 1989. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1992. PEDIPEDINAE (GASTROPODA: ELLOBIIDAE) FROM HONG KONG Ant6nio M. de Frias Martins Departamento de Biologia, Universidade dos A~ores,P-9502 Ponta Delgada, Siio Miguel, A~ores,Portugal ABSTRACT Two species of Pedipedinae are recorded for the first time from Hong Kong and are here provisionally referred to as Pedipes jouani Montrouzier, 1862 and Microtralia alba (Gassies, 1865), described from New Caledonia. A descriptive study of the reproductive and nervous systems was conducted and confirms previous studies that both genera are consubfamilial. The distribution and dispersal of the species is discussed. INTRODUCTION The Indo-Pacific Ellobiidae are particularly well represented by conspicuous, mangrove- dwelling, macroscopic species, relatively few of which have been studied anatomically. Koslowsky (1933) presented a detailed description of Melampus boholensis 'H. and A. Adams' Pfeiffer, 1856. Morton (1955) described the anatomy of Pythia Roding, 1798, Ellobium Roding, 1798 [E.aurisjudae (L. 1758)l and of the small pedipedinian Marinula King, 1832 [M.filholi Hutton, 18781. Knipper and Meyer (1956) provided good illus- trations of the nervous systems of Ellobium (Auriculodes) gaziensis (Preston, 1913), Cassidula labrella (Deshayes, 1830) and Melampus semisulcatus Mousson, 1869. Cassidula Fhssac, 1821, Ellobium and Pythia were discussed by Beny et al. (1967) and Sumikawa and Miura (1978) studied in detail the reproductive system of Ellobium chinense (Pfeiffer, 1854). -

Reproductive Cycle and Embryonic Development of the Gastropod

Reproductive cycle and embryonic development of the gastropod Melampus coffeus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Ellobiidae) in the Brazilian Northeast Maia, RC.a*, Rocha-Barreira, CA.b and Coutinho, R.c aLaboratório de Ecologia de Manguezais, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Ceará, Campus Acaraú, Av. Desembargador Armando de Sales Louzada, s/n, CEP 62580-000, Acaraú, CE, Brazil bLaboratório de Zoobentos, Instituto de Ciências do Mar, Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC, Av. Abolição, 3207, Meireles, CEP 60165-081, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil cLaboratório de Bioincrustação e Ecologia Bêntica, Departamento de Oceanografia, Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira, Rua Kioto, 253, CEP 28930-000, Arraial do Cabo, RJ, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received October 3, 2011 – Accepted January 25, 2012 – Distributed November 30, 2012 (With 4 figures) Abstract Melampus coffeus belongs to a primitive group of pulmonate mollusks found mainly in the upper levels of the marine intertidal zone. They are common in the neotropical mangroves. Little is known about the biology of this species, particularly about its reproduction. The aim of this study was to 1) characterize the morphology and histology of M. coffeus´ gonad; 2) describe the main gametogenesis events and link them to a range of maturity stages; 3) chronologically evaluate the frequency of the different maturity stages and their relation to environmental factors such as water, air and sediment temperatures, relative humidity, salinity and rainfall; and 4) characterize M. coffeus´ spawning, eggs and newly hatched veliger larvae. Samples were collected monthly between February, 2007 and January, 2009 from the mangroves of Praia de Arpoeiras, Acaraú County, State of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. -

Guide to Common Tidal Marsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern

- J Mississippi Alabama Sea Grant Consortium MASGP - 79 - 004 Guide to Common Tidal Marsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern Gulf of Mexico by Richard W. Heard University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688 and Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, Ocean Springs, MS 39564* Illustrations by Linda B. Lutz This work is a result of research sponsored in part by the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, Office of Sea Grant, under Grant Nos. 04-S-MOl-92, NA79AA-D-00049, and NASIAA-D-00050, by the Mississippi-Alabama Sea Gram Consortium, by the University of South Alabama, by the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, and by the Marine Environmental Sciences Consortium. The U.S. Government is authorized to produce and distribute reprints for govern mental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation that may appear hereon. • Present address. This Handbook is dedicated to WILL HOLMES friend and gentleman Copyright© 1982 by Mississippi-Alabama Sea Grant Consortium and R. W. Heard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the author. CONTENTS PREFACE . ....... .... ......... .... Family Mysidae. .. .. .. .. .. 27 Order Tanaidacea (Tanaids) . ..... .. 28 INTRODUCTION ........................ Family Paratanaidae.. .. .. .. 29 SALTMARSH INVERTEBRATES. .. .. .. 3 Family Apseudidae . .. .. .. .. 30 Order Cumacea. .. .. .. .. 30 Phylum Cnidaria (=Coelenterata) .. .. .. .. 3 Family Nannasticidae. .. .. 31 Class Anthozoa. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Order Isopoda (Isopods) . .. .. .. 32 Family Edwardsiidae . .. .. .. .. 3 Family Anthuridae (Anthurids) . .. 32 Phylum Annelida (Annelids) . .. .. .. .. .. 3 Family Sphaeromidae (Sphaeromids) 32 Class Oligochaeta (Oligochaetes). .. .. .. 3 Family Munnidae . .. .. .. .. 34 Class Hirudinea (Leeches) . .. .. .. 4 Family Asellidae . .. .. .. .. 34 Class Polychaeta (polychaetes).. .. .. .. .. 4 Family Bopyridae . .. .. .. .. 35 Family Nereidae (Nereids). .. .. .. .. 4 Order Amphipoda (Amphipods) . ... 36 Family Pilargiidae (pilargiids). .. .. .. .. 6 Family Hyalidae . -

Noaa 13648 DS1.Pdf

r LOAI<CO Qpy N Guide to Gammon Tidal IVlarsh Invertebrates of the Northeastern Gulf of IVlexico by Richard W. Heard UniversityofSouth Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688 and CiulfCoast Research Laboratory, Ocean Springs, MS39564" Illustrations by rimed:tul""'"' ' "=tel' ""'Oo' OR" Iindu B. I utz URt,i',"::.:l'.'.;,',-'-.,":,':::.';..-'",r;»:.",'> i;."<l'IPUS Is,i<'<i":-' "l;~:», li I lb~'ab2 Thisv,ork isa resultofreseaich sponsored inpart by the U.S. Department ofCommerce, NOAA, Office ofSea Grant, underGrani Nos. 04 8 Mol 92,NA79AA D 00049,and NA81AA D 00050, bythe Mississippi Alabama SeaGrant Consortium, byche University ofSouth Alabama, bythe Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, andby the Marine EnvironmentalSciences Consortium. TheU.S. Government isauthorized toproduce anddistribute reprints forgovern- inentalpurposes notwithstanding anycopyright notation that may appear hereon. *Preseitt address. This Handbook is dedicated to WILL HOLMES friend and gentleman Copyright! 1982by Mississippi hlabama SeaGrant Consortium and R. W. Heard All rightsreserved. No part of thisbook may be reproduced in any manner without permissionfrom the author. Printed by Reinbold Lithographing& PrintingCo., BooneviBe,MS 38829. CONTENTS 27 PREFACE FamilyMysidae OrderTanaidacea Tanaids!,....... 28 INTRODUCTION FamilyParatanaidae........, .. 29 30 SALTMARSH INVERTEBRATES ., FamilyApseudidae,......,... Order Cumacea 30 PhylumCnidaria =Coelenterata!......, . FamilyNannasticidae......,... 31 32 Class Anthozoa OrderIsopoda Isopods! 32 Fainily Edwardsiidae. FamilyAnthuridae -

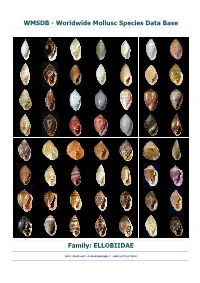

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: ELLOBIIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: HETEROBRANCHIA-PULMONATA-EUPULMONATA-ELLOBIOIDEA ------ Family: ELLOBIIDAE L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (Land) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=34, Subgenus=13, Species=287, Subspecies=12, Synonyms=334, Images=187 acteocinoides , Microtralia acteocinoides J.T. Kuroda & T. Habe, 1961 acuminata , Ovatella acuminata P.M.A. Morelet, 1889 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) acuta , Marinula acuta (D'Orbigny, 1835) acuta , Pythia acuta J.B. Hombron & C.H. Jacquinot, 1847 acutispira , Melampus acutispira W.H. Turton, 1932 - syn of: Melampus parvulus L. Pfeiffer, 1856 adamsianus , Melampus adamsianus L. Pfeiffer, 1855 adansonii , Pedipes adansonii H.M.D. de Blainville, 1824 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) adriatica , Ovatella adriatica H.C. Küster, 1844 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) aegiatilis, Pythia pachyodon aegiatilis H.A. Pilsbry & Y. Hirase, 1908 aequalis , Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) afer , Pedipes afer J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) affinis , Marinula affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Laemodonta affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 alba , Microtralia alba (J. Gassies, 1865) albescens , Ovatella albescens T.V. Wollaston, 1878 - syn of: Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) albovaricosa, Pythia albovaricosa L. Pfeiffer, 1853 albus , Melampus albus C.A. Davis, 1904 - syn of: Melampus monile (J.G.