David R. Castillo, Baroque Horrors: Roots of the Fantastic in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Apish Art': Taste in Early Modern England

‘THE APISH ART’: TASTE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND ELIZABETH LOUISE SWANN PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF YORK ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JULY 2013 Abstract The recent burgeoning of sensory history has produced much valuable work. The sense of taste, however, remains neglected. Focusing on the early modern period, my thesis remedies this deficit. I propose that the eighteenth-century association of ‘taste’ with aesthetics constitutes a restriction, not an expansion, of its scope. Previously, taste’s epistemological jurisdiction was much wider: the word was frequently used to designate trial and testing, experiential knowledge, and mental judgement. Addressing sources ranging across manuscript commonplace books, drama, anatomical textbooks, devotional poetry, and ecclesiastical polemic, I interrogate the relation between taste as a mode of knowing, and contemporary experiences of the physical sense, arguing that the two are inextricable in this period. I focus in particular on four main areas of enquiry: early uses of ‘taste’ as a term for literary discernment; taste’s utility in the production of natural philosophical data and its rhetorical efficacy in the valorisation of experimental methodologies; taste’s role in the experience and articulation of religious faith; and a pervasive contemporary association between sweetness and erotic experience. Poised between acclaim and infamy, the sacred and the profane, taste in the seventeenth century is, as a contemporary iconographical print representing ‘Gustus’ expresses it, an ‘Apish Art’. My thesis illuminates the pivotal role which this ambivalent sense played in the articulation and negotiation of early modern obsessions including the nature and value of empirical knowledge, the attainment of grace, and the moral status of erotic pleasure, attesting in the process to a very real contiguity between different ways of knowing – experimental, empirical, textual, and rational – in the period. -

THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY: THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE E. REID (Under the Direction of Sujata Iyengar) ABSTRACT This dissertation approaches the print book as an epistemologically troubled new media in early modern English culture. I look at the visual interface of emblem books, almanacs, book maps, rhetorical tracts, and commonplace books as a lens for both phenomenological and political crises in the era. At the same historical moment that print expanded as a technology, competing concepts of sight took on a new cultural prominence. Vision became both a political tool and a religious controversy. The relationship between sight and perception in prominent classical sources had already been troubled: a projective model of vision, derived from Plato and Democritus, privileged interior, subjective vision, whereas the receptive model of Aristotle characterized sight as a sensory perception of external objects. The empirical model that assumes a less troubled relationship between sight and perception slowly advanced, while popular literature of the era portrayed vision as potentially deceptive, even diabolical. I argue that early print books actively respond to these visual controversies in their layout and design. Further, the act of interpreting different images, texts, and paratexts lends itself to an oscillation of the reading eye between the book’s different, partial components and its more holistic message. This tension between part and whole appears throughout these books’ technical apparatus and ideological concerns; this tension also echoes the conflict between unity and fragmentation in early modern English national politics. Sight, politics, and the reading process interact to construct the early English print book’s formal aspects and to pull these formal components apart in a process of biblioclasm. -

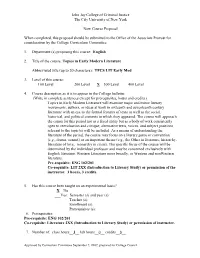

LIT 372 Topics in Early Modern Literature

John Jay College of Criminal Justice The City University of New York New Course Proposal When completed, this proposal should be submitted to the Office of the Associate Provost for consideration by the College Curriculum Committee. 1. Department (s) proposing this course: English 2. Title of the course: Topics in Early Modern Literature Abbreviated title (up to 20 characters): TPCS LIT Early Mod 3. Level of this course: ___100 Level ____200 Level ___X__300 Level ____400 Level 4. Course description as it is to appear in the College bulletin: (Write in complete sentences except for prerequisites, hours and credits.) Topics in Early Modern Literature will examine major and minor literary movements, authors, or ideas at work in sixteenth and seventeenth century literature with an eye to the formal features of texts as well as the social, historical, and political contexts in which they appeared. The course will approach the canon for this period not as a fixed entity but as a body of work consistently open to reevaluation and critique; alternative texts, voices, and subject positions relevant to the topic(s) will be included. As a means of understanding the literature of the period, the course may focus on a literary genre or convention (e.g., drama, sonnet) or an important theme (e.g., the Other in literature, hierarchy, literature of love, monarchy in crisis). The specific focus of the course will be determined by the individual professor and may be concerned exclusively with English literature, Western Literature more broadly, or Western and nonWestern literature. Pre-requisite: ENG 102/201 Co-requisite: LIT 2XX (Introduction to Literary Study) or permission of the instructor. -

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’Ichi)

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) On the Study of Early Modern“ Elegant” Literature Suzuki Ken’ichi On 21 November 2014, I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to talk about my past research at the Research Center for Science Systems affiliated to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. There follows a summary of my talk. (1)Elucidating the distinctive qualities of early-Edo 江戸 literature, with a special focus on “elegant” or “refined”(ga 雅)literature, such as the poetry circles of the emperor Go-Mizunoo 後水尾 and the literary activities of Hayashi Razan 林羅山 . The importance of the study of “elegant” literature ・Up until around the 1970s interest in the field of early modern, or Edo-period, literature concentrated on figures such as Bashō 芭蕉,Saikaku 西鶴,and Chikamatsu 近松 of the Genroku 元禄 era(1688─1704)and Sanba 三馬,Ikku 一 九,and Bakin 馬 琴 of the Kasei 化 政 era(1804─30), and the literature of this period tended to be considered to possess a high degree of “common” or “popular”(zoku 俗)appeal. This was linked to a tendency, influenced by postwar views of history and literature, to hold in high regard that aspect of early modern literature in which “commoners resisted the oppression of the feudal 39 On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) system.” But when considered in light of the actual situation at the time, there can be no doubt that ga literature in the form of poetry written in both Japanese (waka 和歌)and Chinese(kanshi 漢詩), with its strong traditions, was a major presence in terms of both its authority and the formation of literary currents of thought. -

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Marie Weixel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. John Watkins, Adviser April 2009 © Elizabeth Marie Weixel, 2009 i Acknowledgements In such a wood of words … …there be more ways to the wood than one. —John Milton, A Brief History of Moscovia (1674) —English proverb Many people have made this project possible and fruitful. My greatest thanks go to my adviser, John Watkins, whose expansive expertise, professional generosity, and evident faith that I would figure things out have made my graduate studies rewarding. I count myself fortunate to have studied under his tutelage. I also wish to thank the members of my committee: Rebecca Krug for straightforward and honest critique that made my thinking and writing stronger, Shirley Nelson Garner for her keen attention to detail, and Lianna Farber for her kind encouragement through a long process. I would also like to thank the University of Minnesota English Department for travel and research grants that directly contributed to this project and the Graduate School for the generous support of a 2007-08 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. Fellow graduate students and members of the Medieval and Early Modern Research Group provided valuable support, advice, and collegiality. I would especially like to thank Elizabeth Ketner for her generous help and friendship, Ariane Balizet for sharing what she learned as she blazed the way through the dissertation and job search, Marcela Kostihová for encouraging my early modern interests, and Lindsay Craig for his humor and interest in my work. -

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Thomas Gaubatz All rights reserved ABSTRACT Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz This dissertation examines the ways in which the narrative fiction of early modern (1600- 1868) Japan constructed urban identity and explored its possibilities. I orient my study around the social category of chōnin (“townsman” or “urban commoner”)—one of the central categories of the early modern system of administration by status group (mibun)—but my concerns are equally with the diversity that this term often tends to obscure: tensions and stratifications within the category of chōnin itself, career trajectories that straddle its boundaries, performative forms of urban culture that circulate between commoner and warrior society, and the possibility (and occasional necessity) of movement between chōnin society and the urban poor. Examining a range of genres from the late 17th to early 19th century, I argue that popular fiction responded to ambiguities, contradictions, and tensions within urban society, acting as a discursive space where the boundaries of chōnin identity could be playfully probed, challenged, and reconfigured, and new or alternative social roles could be articulated. The emergence of the chōnin is one of the central themes in the sociocultural history of early modern Japan, and modern scholars have frequently characterized the literature this period as “the literature of the chōnin.” But such approaches, which are largely determined by Western models of sociocultural history, fail to apprehend the local specificity and complexity of status group as a form of social organization: the chōnin, standing in for the Western bourgeoisie, become a unified and monolithic social body defined primarily in terms of politicized opposition to the ruling warrior class. -

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses)

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses) 【Arts and Letters Studies】 *Subject* *CREDITS* Ancient Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Ancient Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature A (Prose) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature B (Poetry) 4 Modern Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Modern Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Japanese Language A (Ancient) 4 Japanese Language B (Modern) 4 Classical Chinese Literature 4 Library Science(Books as Cultural Objects) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies A(Classical) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies B(Modern) 4 English Expression I(Basic English Composition 2 English Expression Ⅱ(Advanced Writing Practice) 2 English Academic Writing I(Introduction to the Reserch Paper) 2 English Academic Writing Ⅱ(Practice in Writing Research Paper) 2 Topics in English Linguistics A(Linguistics for Literary Research) 4 Topics in English Linguistics B(Linguistics and Communicaton) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature A (Medieval Literature) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature B (Early Modern Literature) 4 Modern British Literature I(Modern British Literature) 2 Modern British Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary British Literature) 2 Modern American LiteratureⅠ(Modern) 2 Modern American Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature I (British criticism) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature Ⅱ (American criticism) 2 Reading Modern British and AmericanLiteratureA(British and American Drama) 2 Reading Modern British and -

Timothy Hampton

Hampton 1 Curriculum Vitae -- Timothy Hampton Coordinates Department of Comparative Literature, Department of French 4125 Dwinelle Hall #2580 University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 642-2712 [email protected] Website: www.timothyhampton.org Employment 2017- Director, Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, UC Berkeley 1999-Present. Professor of French, and Comparative Literature (“below the line” appointment in Italian Studies), University of California, Berkeley 2014-ongoing. Holder of the Aldo Scaglione and Marie M. Burns Distinguished Professorship, UC Berkeley 2007-2011, Holder of the Bernie H. Williams Chair of Comparative Literature 1990-1999. Associate Professor of French, U.C. Berkeley 1986-1990. Assistant Professor of French, Yale University, New Haven, CT Visiting Positions 2019 (spring) Visiting Professor, University of Paris 8, Paris, France 2001 (spring) Comparative Literature, Stanford University 1994 (fall) French and Italian, Stanford University 1999 (summer) French Cultural Studies Institute, Dartmouth College Education Ph. D., Comparative Literature, Princeton University, 1987 M.A., Comparative Literature, University of Toronto, 1982 B.A., French and Spanish, University of New Mexico, summa cum laude, 1977 Languages Spanish, French, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, German, some Old Provençal, English Fellowships and Honors Fellow of the Institut d'Études Avancées, Paris (2014-15) Associate Researcher, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Paris, May-June 2015. Cox Family Distinguished Fellow in the Humanities, University of Colorado (2014) Campus Distinguished Teaching Award, UC Berkeley (2013) Hampton 2 Major Grant, Institute for International Education, UC Berkeley, "Diplomacy and Culture." 2012-13. Founding Research Network Member, Cambridge/Oxford University project on "Textual Ambassadors." 2012- (With Support from the Humanities Council of the UK). -

SAA Seminar on Landscape, Space and Place in Early Modern Literature Final Abstracts and Bios, Vancouver 2015 Elizabeth Acosta B

SAA seminar on Landscape, Space and Place in Early Modern Literature Final abstracts and bios, Vancouver 2015 Elizabeth Acosta Bio: Elizabeth Acosta is a graduate student of Literary and Cultural Studies Before 1700 at Wayne State University. Her focus is on early modern dramatic works, especially Shakespeare with interests in feminist (and ecofeminist), queer, and gender studies. Abstract: In Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Phoebe accuses Ganymede (the disguised Rosalind) of causing her “much ungentleness” (5.2.67). Though the accusation is focused specifically on Ganymede’s indiscretion with the letter Phoebe has sent to him, I propose that Ganymede’s “ungentleness” towards Phoebe is consistent throughout their interactions, and representative of Rosalind’s “ungentleness” towards nature itself. As the central figure of As You Like It, Rosalind is often the focus of scholarship on this play. Even while analyzing Rosalind’s actions, this paper will bring to the foreground Phoebe, a rich character, very often overlooked. This ecofeminist approach not only highlights a peripheral character but also offers a reconsideration of Rosalind, one in which, I argue, she contaminates the green space that Phoebe inhabits. Douglas Clark Bio: Douglas Clark is a PhD candidate at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. His research examines the literary and philosophical conceptualization of the will in early modern English writing. He is currently completing an essay entitled “The Will and Testamentary Eroticism in Shakespearean Drama” which will appear -

The Five Senses in Medieval and Early Modern England Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture

The Five Senses in Medieval and Early Modern England Intersections Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture General Editor Karl A.E. Enenkel (Chair of Medieval and Neo-Latin Literature Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster e-mail: kenen_01@uni_muenster.de) Editorial Board W. van Anrooij (University of Leiden) W. de Boer (Miami University) Chr. Göttler (University of Bern) J.L. de Jong (University of Groningen) W.S. Melion (Emory University) R. Seidel (Goethe University Frankfurt am Main) P.J. Smith (University of Leiden) J. Thompson (Queen’s University Belfast) A. Traninger (Freie Universität Berlin) C. Zittel (University of Stuttgart) C. Zwierlein (Harvard University) VOLUME 44 – 2016 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/inte The Five Senses in Medieval and Early Modern England Edited by Annette Kern-Stähler Beatrix Busse Wietse de Boer LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: The late ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Fuller Brooch, showing the earliest known personification of the Five Senses. Hammered silver and niello, diameter: 11.4 cm. London, British Museum. Image © Trustees of the British Museum. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016008197 Want or need Open Access? Brill Open offers you the choice to make your research freely accessible online in exchange for a publication charge. Review your various options on brill.com/brill-open. Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1568-1181 isbn 978-90-04-31548-8 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-31549-5 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

1 Conceptions of Love and Death in Early Modern Literature Jessica

Conceptions of Love and Death in Early Modern Literature Jessica Dyson, University of Portsmouth. Niamh Cooney, University of Leeds. Jana Pridalova, University of Leeds. As Michael Neill has argued, “‘death’ is not something that can be imagined once and for all, but an idea that has to be constantly re-imagined across cultures and through time; which is to say that, like most human experiences that we think of as ‘natural’, it is culturally defined” (2). We might, of course, argue that the same is true of “love” and “desire”. Philosophical, theological, medical and literary discourse all help to shape understandings of both love and death in different places and different periods. This special issue, arising from a one day conference held at the University of Leeds under the auspices of the Northern Renaissance Seminars, seeks to explore the cultural constructions of “love” and “death” in the early modern period, and in particular how these topics inform the representation and understanding of each other in early modern literature. Moreover, our contributors are concerned with the ways in which images of love and death provide opportunities to reflect upon broader religious, political and cultural concerns of the period. As Neill’s argument suggests, constructions of love and death are not unchanging. However, they also do not merely appear spontaneously. Each of the essays in this special issue engages not only with the immediate contexts of the texts under consideration, but also, to a greater or lesser extent, with earlier understandings and constructions, such as biblical argument and story, classical philosophy, epyllion, confession, complaint and Petrarchan tropes of love. -

Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England Myers, Anne M

Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England Myers, Anne M. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Myers, Anne M. Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.20565. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/20565 [ Access provided at 26 Sep 2021 14:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England This page intentionally left blank Literature and Architecture in Early Modern England anne m. myers The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2013 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2013 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Myers, Anne M. Literature and architecture in early modern England / Anne M. Myers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4214-0722-7 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-1-4214-0800-2 (electronic) — ISBN 1-4214-0722-1 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) — ISBN 1-4214-0800-7 (electronic) 1. English literature—Early modern, 1500–1700—History and criticism. 2. Architecture and literature—History—16th century. 3. Architecture and literature—History—17th century. I. Title. PR408.A66M94 2013 820.9'357—dc23 2012012207 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.