'The Apish Art': Taste in Early Modern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egan, Gabriel. 2004E. 'Pericles and the Textuality of Theatre'

Egan, Gabriel. 2004e. 'Pericles and the Textuality of Theatre': A Paper Delivered at the Conference 'From Stage to Print in Early Modern England' at the Huntington Library, San Marino CA, USA, 19-20 March "Pericles" and the textuality of theatre" by Gabriel Egan The subtitle of our meeting, 'From Stage to Print in Early Modern England, posits a movement in one direction, from performance to printed book. This seems reasonable since, whereas modern actors usually start with a printed text of some form, we are used to the idea that early modern actors started with manuscripts and that printing followed performance. In fact, the capacity of a printed play to originate fresh performances was something that the title-pages and the preliminary matter of the first play printings in the early sixteenth century made much of. Often the printings helped would-be performers by listing the parts to be assigned, indicating which could be taken by a single actor, and even how to cut the text for a desired performance duration: . yf ye hole matter be playd [this interlude] wyl conteyne the space of an hour and a halfe but yf ye lyst ye may leue out muche of the sad mater as the messengers p<ar>te and some of the naturys parte and some of experyens p<ar>te & yet the matter wyl depend conuenytently and than it wyll not be paste thre quarters of an hour of length (Rastell 1520?, A1r) The earliest extant printed play in English is Henry Medwall's Fulgens and Lucrece (Medwall 1512-16) but the tradition really begins with the printing of the anonymous Summoning of Every Man (Anonymous c.1515) that W. -

THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY: THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE E. REID (Under the Direction of Sujata Iyengar) ABSTRACT This dissertation approaches the print book as an epistemologically troubled new media in early modern English culture. I look at the visual interface of emblem books, almanacs, book maps, rhetorical tracts, and commonplace books as a lens for both phenomenological and political crises in the era. At the same historical moment that print expanded as a technology, competing concepts of sight took on a new cultural prominence. Vision became both a political tool and a religious controversy. The relationship between sight and perception in prominent classical sources had already been troubled: a projective model of vision, derived from Plato and Democritus, privileged interior, subjective vision, whereas the receptive model of Aristotle characterized sight as a sensory perception of external objects. The empirical model that assumes a less troubled relationship between sight and perception slowly advanced, while popular literature of the era portrayed vision as potentially deceptive, even diabolical. I argue that early print books actively respond to these visual controversies in their layout and design. Further, the act of interpreting different images, texts, and paratexts lends itself to an oscillation of the reading eye between the book’s different, partial components and its more holistic message. This tension between part and whole appears throughout these books’ technical apparatus and ideological concerns; this tension also echoes the conflict between unity and fragmentation in early modern English national politics. Sight, politics, and the reading process interact to construct the early English print book’s formal aspects and to pull these formal components apart in a process of biblioclasm. -

Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England

Textual Ghosts: Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Ellen Clark, M.A. English Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Dutton, Advisor Christopher Highley Alan Farmer Copyright by Rachel Ellen Clark 2011 Abstract This dissertation argues that during the reign of Charles I (1625-42), a powerful and long-lasting nationalist discourse emerged that embodied a conflicted nostalgia and located a primary source of English national identity in the Elizabethan era, rooted in the works of William Shakespeare, Sir Philip Sidney, John Lyly, and Ben Jonson. This Elizabethanism attempted to reconcile increasingly hostile conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, court and country, and elite and commoners. Remarkably, as I show by examining several Caroline texts in which Elizabethan ghosts appear, Caroline authors often resurrect long-dead Elizabethan figures to articulate not only Puritan views but also Arminian and Catholic ones. This tendency to complicate associations between the Elizabethan era and militant Protestantism also appears in Caroline plays by Thomas Heywood, Philip Massinger, and William Sampson that figure Queen Elizabeth as both ideally Protestant and dangerously ambiguous. Furthermore, Caroline Elizabethanism included reprintings and adaptations of Elizabethan literature that reshape the ideological significance of the Elizabethan era. The 1630s quarto editions of Shakespeare’s Elizabethan comedies The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Taming of the Shrew, and Love’s Labour’s Lost represent the Elizabethan era as the source of a native English wit that bridges social divides and negotiates the ii roles of powerful women (a renewed concern as Queen Henrietta Maria became more conspicuous at court). -

|||GET||| Ben Jonson 1St Edition

BEN JONSON 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John Palmer | 9781315302188 | | | | | Ben Jonson folios The playbook itself is a mixture of halfsheets folded and gathered into quarto format, supplemented by a handful of full sheets also gathered in quarto and used for the final quires. Robert Allott contracted John Benson to print the first three plays of an intended second Ben Jonson 1st edition volume of Jonson's collected works, including Bartholomew Fair never registered ; The Staple of News entered to John Waterson 14 AprilArber 4. Views Read Edit View history. He reinstated the coda in F1. Occasional mispagination, as issued, text complete. See Lockwood, Shipping and insurance charges are additional. Gants and Tom Lockwood When Ben Jonson first emerged as a playwright at the end of Elizabeth's reign, the English printing and bookselling trade that would preserve his texts for posterity was still a relatively small industry. Markings on first page and title page. Each volume in the series, initially under the direction of Willy Bang and later Henry De Vocht, sought to explore how compositors and correctors shaped the work, and included extensive analyses of the press variants between individual copies of a playbook as well as Ben Jonson 1st edition variants between editions. More information about this seller Contact this seller 1. Seemingly unhindered by concerns over time or space or materials, the Oxford editors included along with the texts a Jonson biography summing up all that was known of the poet and playwright at the time, a first-rate set of literary annotations and glosses, invaluable commentary on all the plays, and other essential secondary resources such as a stage history of the plays, Jonsonian allusions, and a reconstruction of Jonson's personal library. -

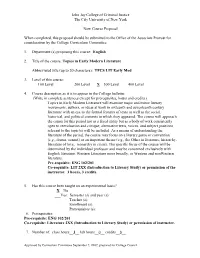

LIT 372 Topics in Early Modern Literature

John Jay College of Criminal Justice The City University of New York New Course Proposal When completed, this proposal should be submitted to the Office of the Associate Provost for consideration by the College Curriculum Committee. 1. Department (s) proposing this course: English 2. Title of the course: Topics in Early Modern Literature Abbreviated title (up to 20 characters): TPCS LIT Early Mod 3. Level of this course: ___100 Level ____200 Level ___X__300 Level ____400 Level 4. Course description as it is to appear in the College bulletin: (Write in complete sentences except for prerequisites, hours and credits.) Topics in Early Modern Literature will examine major and minor literary movements, authors, or ideas at work in sixteenth and seventeenth century literature with an eye to the formal features of texts as well as the social, historical, and political contexts in which they appeared. The course will approach the canon for this period not as a fixed entity but as a body of work consistently open to reevaluation and critique; alternative texts, voices, and subject positions relevant to the topic(s) will be included. As a means of understanding the literature of the period, the course may focus on a literary genre or convention (e.g., drama, sonnet) or an important theme (e.g., the Other in literature, hierarchy, literature of love, monarchy in crisis). The specific focus of the course will be determined by the individual professor and may be concerned exclusively with English literature, Western Literature more broadly, or Western and nonWestern literature. Pre-requisite: ENG 102/201 Co-requisite: LIT 2XX (Introduction to Literary Study) or permission of the instructor. -

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’Ichi)

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) On the Study of Early Modern“ Elegant” Literature Suzuki Ken’ichi On 21 November 2014, I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to talk about my past research at the Research Center for Science Systems affiliated to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. There follows a summary of my talk. (1)Elucidating the distinctive qualities of early-Edo 江戸 literature, with a special focus on “elegant” or “refined”(ga 雅)literature, such as the poetry circles of the emperor Go-Mizunoo 後水尾 and the literary activities of Hayashi Razan 林羅山 . The importance of the study of “elegant” literature ・Up until around the 1970s interest in the field of early modern, or Edo-period, literature concentrated on figures such as Bashō 芭蕉,Saikaku 西鶴,and Chikamatsu 近松 of the Genroku 元禄 era(1688─1704)and Sanba 三馬,Ikku 一 九,and Bakin 馬 琴 of the Kasei 化 政 era(1804─30), and the literature of this period tended to be considered to possess a high degree of “common” or “popular”(zoku 俗)appeal. This was linked to a tendency, influenced by postwar views of history and literature, to hold in high regard that aspect of early modern literature in which “commoners resisted the oppression of the feudal 39 On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) system.” But when considered in light of the actual situation at the time, there can be no doubt that ga literature in the form of poetry written in both Japanese (waka 和歌)and Chinese(kanshi 漢詩), with its strong traditions, was a major presence in terms of both its authority and the formation of literary currents of thought. -

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Marie Weixel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. John Watkins, Adviser April 2009 © Elizabeth Marie Weixel, 2009 i Acknowledgements In such a wood of words … …there be more ways to the wood than one. —John Milton, A Brief History of Moscovia (1674) —English proverb Many people have made this project possible and fruitful. My greatest thanks go to my adviser, John Watkins, whose expansive expertise, professional generosity, and evident faith that I would figure things out have made my graduate studies rewarding. I count myself fortunate to have studied under his tutelage. I also wish to thank the members of my committee: Rebecca Krug for straightforward and honest critique that made my thinking and writing stronger, Shirley Nelson Garner for her keen attention to detail, and Lianna Farber for her kind encouragement through a long process. I would also like to thank the University of Minnesota English Department for travel and research grants that directly contributed to this project and the Graduate School for the generous support of a 2007-08 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. Fellow graduate students and members of the Medieval and Early Modern Research Group provided valuable support, advice, and collegiality. I would especially like to thank Elizabeth Ketner for her generous help and friendship, Ariane Balizet for sharing what she learned as she blazed the way through the dissertation and job search, Marcela Kostihová for encouraging my early modern interests, and Lindsay Craig for his humor and interest in my work. -

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Thomas Gaubatz All rights reserved ABSTRACT Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz This dissertation examines the ways in which the narrative fiction of early modern (1600- 1868) Japan constructed urban identity and explored its possibilities. I orient my study around the social category of chōnin (“townsman” or “urban commoner”)—one of the central categories of the early modern system of administration by status group (mibun)—but my concerns are equally with the diversity that this term often tends to obscure: tensions and stratifications within the category of chōnin itself, career trajectories that straddle its boundaries, performative forms of urban culture that circulate between commoner and warrior society, and the possibility (and occasional necessity) of movement between chōnin society and the urban poor. Examining a range of genres from the late 17th to early 19th century, I argue that popular fiction responded to ambiguities, contradictions, and tensions within urban society, acting as a discursive space where the boundaries of chōnin identity could be playfully probed, challenged, and reconfigured, and new or alternative social roles could be articulated. The emergence of the chōnin is one of the central themes in the sociocultural history of early modern Japan, and modern scholars have frequently characterized the literature this period as “the literature of the chōnin.” But such approaches, which are largely determined by Western models of sociocultural history, fail to apprehend the local specificity and complexity of status group as a form of social organization: the chōnin, standing in for the Western bourgeoisie, become a unified and monolithic social body defined primarily in terms of politicized opposition to the ruling warrior class. -

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses)

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses) 【Arts and Letters Studies】 *Subject* *CREDITS* Ancient Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Ancient Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature A (Prose) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature B (Poetry) 4 Modern Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Modern Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Japanese Language A (Ancient) 4 Japanese Language B (Modern) 4 Classical Chinese Literature 4 Library Science(Books as Cultural Objects) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies A(Classical) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies B(Modern) 4 English Expression I(Basic English Composition 2 English Expression Ⅱ(Advanced Writing Practice) 2 English Academic Writing I(Introduction to the Reserch Paper) 2 English Academic Writing Ⅱ(Practice in Writing Research Paper) 2 Topics in English Linguistics A(Linguistics for Literary Research) 4 Topics in English Linguistics B(Linguistics and Communicaton) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature A (Medieval Literature) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature B (Early Modern Literature) 4 Modern British Literature I(Modern British Literature) 2 Modern British Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary British Literature) 2 Modern American LiteratureⅠ(Modern) 2 Modern American Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature I (British criticism) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature Ⅱ (American criticism) 2 Reading Modern British and AmericanLiteratureA(British and American Drama) 2 Reading Modern British and -

Timothy Hampton

Hampton 1 Curriculum Vitae -- Timothy Hampton Coordinates Department of Comparative Literature, Department of French 4125 Dwinelle Hall #2580 University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 642-2712 [email protected] Website: www.timothyhampton.org Employment 2017- Director, Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, UC Berkeley 1999-Present. Professor of French, and Comparative Literature (“below the line” appointment in Italian Studies), University of California, Berkeley 2014-ongoing. Holder of the Aldo Scaglione and Marie M. Burns Distinguished Professorship, UC Berkeley 2007-2011, Holder of the Bernie H. Williams Chair of Comparative Literature 1990-1999. Associate Professor of French, U.C. Berkeley 1986-1990. Assistant Professor of French, Yale University, New Haven, CT Visiting Positions 2019 (spring) Visiting Professor, University of Paris 8, Paris, France 2001 (spring) Comparative Literature, Stanford University 1994 (fall) French and Italian, Stanford University 1999 (summer) French Cultural Studies Institute, Dartmouth College Education Ph. D., Comparative Literature, Princeton University, 1987 M.A., Comparative Literature, University of Toronto, 1982 B.A., French and Spanish, University of New Mexico, summa cum laude, 1977 Languages Spanish, French, Italian, Latin, Portuguese, German, some Old Provençal, English Fellowships and Honors Fellow of the Institut d'Études Avancées, Paris (2014-15) Associate Researcher, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Paris, May-June 2015. Cox Family Distinguished Fellow in the Humanities, University of Colorado (2014) Campus Distinguished Teaching Award, UC Berkeley (2013) Hampton 2 Major Grant, Institute for International Education, UC Berkeley, "Diplomacy and Culture." 2012-13. Founding Research Network Member, Cambridge/Oxford University project on "Textual Ambassadors." 2012- (With Support from the Humanities Council of the UK). -

SAA Seminar on Landscape, Space and Place in Early Modern Literature Final Abstracts and Bios, Vancouver 2015 Elizabeth Acosta B

SAA seminar on Landscape, Space and Place in Early Modern Literature Final abstracts and bios, Vancouver 2015 Elizabeth Acosta Bio: Elizabeth Acosta is a graduate student of Literary and Cultural Studies Before 1700 at Wayne State University. Her focus is on early modern dramatic works, especially Shakespeare with interests in feminist (and ecofeminist), queer, and gender studies. Abstract: In Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Phoebe accuses Ganymede (the disguised Rosalind) of causing her “much ungentleness” (5.2.67). Though the accusation is focused specifically on Ganymede’s indiscretion with the letter Phoebe has sent to him, I propose that Ganymede’s “ungentleness” towards Phoebe is consistent throughout their interactions, and representative of Rosalind’s “ungentleness” towards nature itself. As the central figure of As You Like It, Rosalind is often the focus of scholarship on this play. Even while analyzing Rosalind’s actions, this paper will bring to the foreground Phoebe, a rich character, very often overlooked. This ecofeminist approach not only highlights a peripheral character but also offers a reconsideration of Rosalind, one in which, I argue, she contaminates the green space that Phoebe inhabits. Douglas Clark Bio: Douglas Clark is a PhD candidate at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow. His research examines the literary and philosophical conceptualization of the will in early modern English writing. He is currently completing an essay entitled “The Will and Testamentary Eroticism in Shakespearean Drama” which will appear -

Shakespeare and Hospitality

Shakespeare and Hospitality This volume focuses on hospitality as a theoretically and historically cru- cial phenomenon in Shakespeare’s work with ramifications for contempo- rary thought and practice. Drawing a multifaceted picture of Shakespeare’s numerous scenes of hospitality—with their depictions of greeting, feeding, entertaining, and sheltering—the collection demonstrates how hospital- ity provides a compelling frame for the core ethical, political, theological, and ecological questions of Shakespeare’s time and our own. By reading Shakespeare’s plays in conjunction with contemporary theory as well as early modern texts and objects—including almanacs, recipe books, hus- bandry manuals, and religious tracts—this book reimagines Shakespeare’s playworld as one charged with the risks of hosting (rape and seduction, war and betrayal, enchantment and disenchantment) and the limits of gen- erosity (how much can or should one give the guest, with what attitude or comportment, and under what circumstances?). This substantial volume maps the terrain of Shakespearean hospitality in its rich complexity, offering key historical, rhetorical, and phenomenological approaches to this diverse subject. David B. Goldstein is Associate Professor of English at York University, Canada. Julia Reinhard Lupton is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine. Routledge Studies in Shakespeare 1 Shakespeare and Philosophy 10 Embodied Cognition and Stanley Stewart Shakespeare’s Theatre The Early Modern 2 Re-playing Shakespeare in Asia Body-Mind Edited by Poonam Trivedi and Edited by Laurie Johnson, Minami Ryuta John Sutton, and Evelyn Tribble 3 Crossing Gender in Shakespeare Feminist Psychoanalysis and the 11 Mary Wroth and Difference Within Shakespeare James W.