The First100 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Student's Guide to the Leading Law Firms and Sets in the UK

2021 The student’s guide to the leading law firms and sets in the UK e-Edition chambers-student.com Connect with us on cbaK Travers Smith’s mix of formal and informal training is second to none. It enables those coming fresh from law school to quickly become familiar with complex concepts and provides them with the necessary tools to throw themselves into their team’s work right from the start. www.traverssmith.com 10 Snow Hill, London EC1A 2AL +44 (0) 20 7295 3000 Contents Law school The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) p.37 An introduction to the SQE with ULaw p.41 Solicitors’ timetable p.43 Barristers’ timetable p.44 The Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) p.45 The Legal Practice Course (LPC) p.49 The Bar Course p.52 How to fund law school p.55 Law school course providers p.57 Contents https://www.chambersstudent.co.uk The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) The Solicitors Qualifying Exam (SQE) From 2021 there’s going to be an entirely new way of qualifying as a solicitor replacing the GDL, LPC and training contract. If you’re thinking ‘SQE OMG!’ – don’t fear: here’s a quick guide. What’s going on? volve a practical testing ‘pilot’ with students. The regula- In winter 2016/17 the Solicitors Regulation Authority tor has stated that it expects various other providers (i.e. (SRA) dropped a bombshell on the legal profession: it was probably law schools and the current GDL/LPC providers) going ahead with its plan for the Solicitors Qualifying Ex- to offer preparatory courses for both stages of the SQE. -

Solicitor Apprenticeships Employer Fact Sheet

Academic excellence for business and the professions Solicitor Apprenticeships Employer Fact Sheet Overview of the Scheme The City Law School and CILEx Law School Trailblazer Solicitor Apprenticeships Trailblazer Solicitor Apprenticeships are The apprenticeship offers on and off the job are an exciting development for an exciting development for the legal learning consisting of work-based training the legal profession – both for profession – both for employers and the next and part-time studying. generation of solicitors. employers and the next generation In order to demonstrate their ability, of solicitors. In September 2015 the Department for apprentices will be rigorously assessed to Business, Innovation and Skills announced ensure they meet stringent requirements. The City Law School has been at the Legal Trailblazer Scheme which The City Law School has entered into a enables apprentices to qualify as a solicitor, unique partnership with CILEx Law School the forefront of the launch of this paralegal or chartered legal executive. to deliver a blended online and face-to-face new scheme since its introduction learning experience. in 2016. The City Law School successfully launched the programme in September 2016. The The City Law School is part of City, solicitor route allows students to sign University of London. City has a long up straight from school to a six year tradition of excellence in legal education programme, the completion of which will and in 2015 the National Student Survey lead to qualification as a solicitor. This is found that City was the top university in ‘Choosing an apprenticeship over the an alternative to the traditional routes of London for student satisfaction. -

Nottingham Law Journal

NOTTINGHAM LAW JOURNAL VOL. 19(1) 2010 Guest Editor Rebecca Huxley-Binns, LLB (Uclan), FHEA Editor Mr Tom Lewis, BA (Oxon), Solicitor Assistant Editor Ms Jane Jarman, BA (Leicester), ACIArb, Solicitor Advisory Board The Rt Hon the Lord Saville of Newdigate Prof Stephen Weatherill, University of Oxford Judge Bostjan Zupancic, the European Court of Human Rights The Rt Hon Sir Philip Otton Prof Mark Findlay, University of Sydney Prof Conor Gearty, London School of Economics Mr Jonathan Griffiths, Queen Mary & Westfield College, London Prof Michael J. Gunn, University of Derby Prof Martin Hunter, Essex Court Chambers & Nottingham Prof Geraint Howells, University of Manchester Law School Prof Peter Jones, Nottingham Trent University Mr Roger Leng, University of Warwick Prof Robert G. Lee, Cardiff Law School Mr Gary Watt, University of Warwick Miss Helen Milgate, Solicitor Prof Neil Peck, Attorney, Snell & Wilmer, Denver, Mr Christopher Muttukumaru, Director of Legal Col, USA & Nottingham Law School Services, Department of Transport Prof Barry Rider, University of Cambridge Prof John Peysner, University of Lincoln Mr Paul Smith, Partner, Eversheds Prof Mary Seneviratne, Nottingham Law School Mr John Snape, Warwick University Mr Marc S. Stauch, Leibnitz University, Hannover Dr Kim Stevenson, University of Plymouth Prof Adrian Walters, Nottingham Law School Dr Christian Twigg-Flesner, University of Hull Editorial Board Mr Graham Ferris, LLB (Nott), Solicitor Prof Ralph Henham LLB (Leicester), MA (Keele), MPhil (Nott), Ph D (Keele), Solicitor Ms Andrea Nicholson, LLB (Buckinghamshire), LLM (Durham) Miss Kay Wheat, BA (Reading), Solicitor Administrative Assistant Ms Carole Vaughan The Nottingham Law Journal is a refereed journal, normally published in Spring and Autumn each year. -

Download PDF (40.2

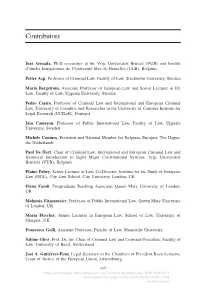

JOBNAME: Mitsilegas PAGE: 8 SESS: 9 OUTPUT: Thu Feb 25 11:50:06 2016 Contributors Inés Armada, Ph.D researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) and Institut d’études Européennes de l’Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Belgium Petter Asp, Professor of Criminal Law, Faculty of Law, Stockholm University, Sweden Maria Bergström, Associate Professor of European Law and Senior Lecturer in EU Law, Faculty of Law, Uppsala University, Sweden Pedro Caeiro, Professor of Criminal Law and International and European Criminal Law, University of Coimbra; and Researcher at the University of Coimbra Institute for Legal Research (UCILeR), Portugal Iain Cameron, Professor of Public International Law, Faculty of Law, Uppsala University, Sweden Michèle Coninsx, President and National Member for Belgium, Eurojust, The Hague, the Netherlands Paul De Hert, Chair of Criminal Law, International and European Criminal Law and Historical Introduction to Eight Major Constitutional Systems, Vrije Universiteit Brussels (VUB), Belgium Elaine Fahey, Senior Lecturer in Law, Co-Director, Institute for the Study of European Law (ISEL), City Law School, City University, London, UK Elena Fasoli, Postgraduate Teaching Associate, Queen Mary University of London, UK Malgosia Fitzmaurice, Professor of Public International Law, Queen Mary University of London, UK Maria Fletcher, Senior Lecturer in European Law, School of Law, University of Glasgow, UK Francesca Galli, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, Maastricht University Sabine Gless, Prof. Dr. iur. Chair of Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure, Faculty of Law, University of Basel, Switzerland José A. Gutiérrez-Fons, Legal Secretary in the Chambers of President Koen Lenaerts, Court of Justice of the European Union, Luxembourg viii Valsamis Mitsilegas, Maria Bergström and Theodore Konstadinides - 9781783473311 Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/29/2021 07:57:21AM via free access Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Mitsilegas-Research_handbook_on_EU_criminal_law / Division: Prelims /Pg. -

The Unpopularity of Property Law Modules: Popular Culture Offers Solutions

Athens Journal of Law - Volume 5, Issue 3 – Pages 241-254 The Unpopularity of Property Law Modules: Popular Culture offers Solutions * By Anna Chronopoulou The commodification of Legal Education and the popularity of law as a subject of study have been reflected in a plethora of law courses at undergraduate and postgraduate levels on offer in the English Universities. Property Law modules do not necessarily enjoy the same degree of popularity to other modules on a qualifying law degree in English Universities. Despite being slowly changing modules, Property Law modules did not remain unaffected by the commodification of legal education. As a result, Property Law became highly specialised. This quickly translated in optional modules such as: Succession Law, Housing Law, Landlord and Tenant Law, Construction Law etc. Nevertheless, Property Law modules remain highly unpopular among the student population in the English Universities. This paper examines the reasons for this by focusing on three parameters. The first parameter examines the nature of the subject itself as highly technical, therefore less adventurous and attractive. The second parameter brings forward the suggestion that neither legal educators nor researchers have actually successfully managed to break away from the monotony of Property Law subjects. The third parameter proposes solutions to the increasing unpopularity of these subjects. It puts forward the suggestion that a socio-legal approach to the subjects combined with appealing forms of popular culture might just increase the popularity of the subjects among the student population. Keywords: Legal Education, Property Law modules, Popular Culture Introduction Legal education has experienced a number of transformations in England and Wales over the last decades. -

Hamzah Abu-Hassan

Hamzah Abu-Hassan Senior Associate Corporate and M&A Primary practice Corporate and M&A 29/09/2021 Hamzah Abu-Hassan | Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer About Hamzah Abu-Hassan <p><strong>Hamzah advises local and international clients on their corporate and commercial activities. </strong></p> <p>He is experienced in various aspects of the law focusing on private and public M&A, joint ventures, corporate structuring and regulatory matters, and providing general corporate advice.</p> <p>Hamzah has practised law in three different jurisdictions in the Middle East (Jordan, Qatar and UAE) and advised on transactions across the region.</p> <p>Hamzah is fluent in both Arabic and English.</p> Recent work <ul> <li>Advising Kuwait Finance House on its ongoing cross border acquisition by way of share swap of Ahli United Bank in Bahrain. The consolidation is set to create the largest banking entity in Kuwait with assets of $94bn.</li> <li>Advising First Gulf Bank on its merger with National Bank of Abu Dhabi creating First Abu Dhabi Bank, the largest bank in MENA region with US$175bn of assets and a combined market capitalization of approximately $29.1bn.</li> <li>Advising Al Hilal Bank in relation to a three-way merger with Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank and Union National Bank creating the third largest bank in the UAE, with total assets of $114bn.</li> <li>Advising Invest Bank in relation to a $1.1bn capital restructuring by way of strategic investment from the Government of Sharjah.</li> <li>Advising Barwa Bank in Qatar on its merger with International -

Pupillage Supplementary Survey 2010/11

Pupillage Survey 2010/11 An analysis of the backgrounds of pupils registered in 2010/11 Pupillage statistical report March 2012 Dr Jennifer Sauboorah and Caroline Carney Research Department 1 Table of Contents 1. Pupillage: the final stage of training for the Bar................................................................ 8 2. Pupillage registration figures ........................................................................................... 9 3. Equality and diversity monitoring data ........................................................................... 12 4. Age ................................................................................................................................ 13 5. Disability ........................................................................................................................ 14 6. Ethnicity ......................................................................................................................... 15 7. Gender .......................................................................................................................... 18 8. Sexual orientation .......................................................................................................... 19 9. Gender reassignment .................................................................................................... 19 10. Religion or belief ............................................................................................................ 20 11. Marital status ................................................................................................................ -

University Pathways

University pathways INTO_CIT_201819_BROCHURE for international students Contents Academic excellence 4 Why City, University of London? for business and 7 About the University 8 Life at the Centre 10 Discover the City of London the professions 12 Home from home 14 Choosing your course Welcome to INTO City, University of London, 16 International Foundation where your university-validated programme will 22 Graduate Diploma lead to an internationally-recognised degree 27 Academic English from City, University of London. Together we 28 How to apply have one aim: to give international students 29 Application form like you the opportunity to study at one of the 31 Scholarships most popular universities in the UK for both international and local students, in one of the world’s most exciting cities. INTO City, University of London is an excellent choice. You’ll study a specialist programme designed exclusively for international students and tailored to the requirements of the University. We’ll help you to improve your English language, adjust to life as a student in London, and excel in the British education system. You’ll learn in our modern centre in the heart of the city’s financial district, and as a student of the University you’ll enjoy access to facilities on the campus which is just 15 minutes away by bus, or a 30 minute walk. You’ll get to know everything about City, from campus trips to visits and presentations from academics and students. You’ll become part of the University from day one, meaning your success at City is just a short step away. -

Litigation Edited by Evan R Chesler and Timothy G Cameron Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP

CHAMBERS Legal Practice Guides Litigation Edited by Evan R Chesler and Timothy G Cameron Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP 2014 Chambers Legal Practice Guides For more than 20 years, Chambers Legal Guides have ranked lawyers and law firms across the world. Chambers now offer clients a new series of Legal Practice Guides, which contain practical guidance on doing legal business in key jurisdictions. We use our knowledge of the world’s best lawyers to select leading law firms in each jurisdiction to write the ‘Law & Practice’ sections. In addition, the ‘Trends & Developments’ sections analyse trends and developments in local legal markets. The ‘Doing Business In’ sections, based on the views of clients with in-depth international experience, contain hard-won knowledge about typi- cal local problems and how to overcome them – information usually missing from official guides. Disclaimer: The information in this guide is provided for general reference only, not as specific legal advice. Views expressed by the authors are not necessarily the views of the law firms in which they practise. For specific legal advice, a lawyer should be consulted. Publisher Michael Chambers Series Editor Claire Oxborrow Business Development Director Brad Sirott Editorial Contributions Monica Fuertes-Britez Orders to: Chambers & Partners Publishing Published by Chambers & Partners Publishing (a division of Orbach & Chambers Ltd) 39 Parker Street, London WC2B 5PQ Tel +44 20 7606 8844 Fax +44 20 7831 5662 Web www.chambersandpartners.com Copyright © 2014 Michael Chambers and Orbach & Chambers Ltd ISBN: 978-0-85514-684-9 Contents Our eDitorial TeaM....................p.5 iDnTrO uCTiOn.......................................p.17 ALBANIA ..........................................................Doing.Business.In.........................p.25 Law.&.Practice.................................p.29 AUT S RALIA....................................................Doing.Business.In.........................p.41 Trends.&.Developments:. -

Practice with the Professionals Bar Professional Training Course

Academic excellence for business and the professions Practice with the Professionals Bar Professional Training Course www.city.ac.uk/law Contents The City Law School 3 Why choose The City Law School? 4 About us 5 Benefits 6 About you 7 Pro Bono 8 BPTC to LLM 9 Recent publications by BPTC staff 10 2 The City Law School Bar Professional Training Course The City Law School World class legal education in the heart of London The City Law School is one of London’s major law Courses available: Bar Professional Training Course Training Professional Bar schools. Incorporating what was formerly known Undergraduate courses as the Inns Court School of Law, The City Law Law LLB (Hons) School offers an impressive range of academic and professional legal courses, and is the first law school Graduate courses in London to offer students and practitioners all Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL) stages of legal education. Graduate Entry LLB (Hons) Professional courses With four levels of study: undergraduate, Bar Professional Training Course (BPTC) postgraduate, professional and continuing Legal Practice Course (LPC) professional development, we offer courses suitable Legal Practice LLM the Professionals with Practice for anyone interested in following a career in law and are also able to meet the continuing training Professional Legal Skills LLM needs of the profession. Taught Masters Civil Litigation and Dispute Resolution LLM Our distinguished history and exceptional academic Criminal Litigation LLM staff show a commitment to both the students we EU Commercial Law LLM educate and the profession we serve and we have International Banking Law LLM a long-established reputation for excellence and International Business Law LLM (distance learning) innovation in the study and practice of law. -

SLN Winter 2011.Qxd

Socio-LeNo 84 gal NTHE NEE WSLEWTTER OSF THEL SOCIEO-LEGTAL STTUDIESE ASSOR CIATION PRING S 2018 Wills Memorial Building (including a trip up the tower) and slsa BRIsTOl 2018 Brunel’s iconic bridge. To reserve a place on a tour, email Yet again, the Annual Conference is fast approaching! Suzanne Mills e [email protected] (payment in cash This year it will be held at the University of Bristol Law to the tour guide on the day). Full details of the activities can be School from 27 to 29 March 2018. found at w www.slsa2018.com/conference-activities. Bristol is well-served by the transport network and Registration is now open at the late rate, but still with an accessible by rail, car, bus, coach and plane. The website features excellent membership discount. The closing date for all comprehensive details of all travel routes. Accommodation is registrations is 6pm on 19 March 2018 . Be sure not to miss this not included in the conference package, but the Bristol team has important deadline. Visit the website as soon as you can at arranged preferential rates at several city hotels. These can be w www.slsa2018.com. This year we have received over 450 found on the website along with details of other providers abstracts in response to the call for papers and the theme and offering a wide range of prices. There are also a number of stream convenors have been working on putting the panels childcare options available for those with children. For further together. As always, there is a great range of papers and some information and to book your place, visit the conference delegates will no doubt have difficulty choosing between the website: w www.slsa2018.com. -

Appendix 2: a List of the Libraries That Completed the Survey Questionnaire

APPENDIX 2: List of the 124 major law libraries who completed the survey Category 1: University law school libraries Name of library Attached to Institution [Africa] Law Library Imo State University Sir Arko Korsah Law Library Kwame Nkrumah Univ of Science and Technology Law Library Uganda Christian University Brand van Zyl Law Library University of Cape Town GMJ Sweeney Law Library University of KwaZulu Natal Oliver R Tambo Law Library University of Pretoria JS Gericke Library University of Stellenbosch Faculty Law Library University of Zimbabwe Name of library Attached to Institution [North America] Diamond Law Library Columbia Law School H Laddie Montague Jnr Law Library Dickinson Law School, Penn State University J Michael Goodson Law Library Duke Law School Hugh F MacMillan Law Library Emory University Law Library Georgetown University Law School Library Harvard University Loyola LA Law Library Loyola Marymount University Osgoode Hall Law School Library Osgoode Hall Law School - York University William T Muse Law Library Richmond University School of Law Fred Parks Law Library South Texas College of Law Rittenberg Law Library St Johns University Stanford Law Library Stanford University Dolly and Homer Hand Law Library Stetson University College of Law Douglas Barclay Law Library Syracuse University College of Law Tarlton Law Library Texas University School of Law Tulane Law Library Tulane University Law Library UCLA School of Law Bibliotheque de I'universitie Laval Universitie Laval 1 Law Library University of British Columbia Berkeley