Textualization of Self in Pakistani Women's Vernacular Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Faizghar Newsletter

Issue: January Year: 2016 NEWSLETTER Content Faiz Ghar trip to Rana Luxury Resort .............................................. 3 Faiz International Festival ................................................................... 4 Children at FIF ............................................................................................. 11 Comments .................................................................................................... 13 Workshop on Thinking Skills ................................................................. 14 Capacity Building Training workshops at Faiz Ghar .................... 15 [Faiz Ghar Music Class tribute to Rasheed Attre .......................... 16 Faiz Ghar trip to [Rana Luxury Resort The Faiz Ghar yoga class visited the Rana Luxury Resort and Safari Park at Head Balloki on Sunday, 13th December, 2015. The trip started with live music on the tour bus by the Faiz Ghar music class. On reaching the venue, the group found a quiet spot and spread their yoga mats to attend a vigorous yoga session conducted by Yogi Sham- shad Haider. By the time the session ended, the cold had disappeared, and many had taken o their woollies. The time was ripe for a fruit eating session. The more sporty among the group started playing football and frisbee. By this time the musicians had got their act together. The live music and dance session that followed became livelier when a large group of school girls and their teachers joined in. After a lot of food for the soul, the group was ready to attack Gogay kay Chaney, home made koftas, organic salads, and the most delicious rabri kheer. The group then took a tour of the jungle and the safari park. They enjoyed the wonderful ambience of the bamboo jungle, and the ostriches, deers, parakeet, swans, and many other wild animals and birds. Some members also took rides on the train and colour- ful donkey carts. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-Site

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site Title Prof./Dr./Mr. First Name Arjumand Last Ara Photograph /Ms. Name Designation Sr. Assistant Professor Department Urdu Address Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University (Campus) of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) 5/3, University Road, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 91-011-27666266 Mobile 9810598859 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 2001 Thesis topic: Editing of ‘Diwan-e Bayan’ with a Comprehensive Foreword M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1996 Editing of Masnavi Lakht-e Jigar, by Munshi Bal Mukund Besabr M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1994 Subjects: Urdu B.A. Meerut University, U.P. 1988 Subjects: Hindi, English, Geography Career Profile Organization / Institution Designation Duration Role University of Delhi Assistant Professor Since 2006 Teaching and research in Senior Scale University of Delhi Lecturer From Teaching and research 18.11.2002- 2006 National Council for Research Assistant 1999-2002 Editing of monthly Promotion of Urdu educational and literary Language, HRD, New Delhi magazine ‘Urdu Duniya’ Research Interests / Specialization www.du.ac.in Page 1 Research interests: Translations, Progressive Literature, Feminist writing. Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature: Poetry in Delhi in 18th Century Delhi, Progressive Movement of 20th Century 2. Poetry (Ghazal & Nazm): Quli Qutub Shah, Khwaja Mir Dard, Aatish, Ghalib, Iqbal, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Akhtarul Iman 3. Poetry (Masnavi and Qasida): Gulzar-e Nasim by Daya Shankar Nasim, Qasida Na’tiah Madih Khairul Mursalin by Mohsin Kakorvi 4. -

Saturday, 26 April 2014 Friday, 25 April 2014

Friday, 25 April 2014 5.00 – 9.00 p.m. Margala Hall Inauguration Welcome Speeches by Ameena Saiyid and Asif Farrukhi Keynote Speeches by Zehra Nigah and Aamer Hussein Performance by Sheema Kermani Dastangoi by Danish Husain and Darain Shahidi of India and Fawad Khan and Nazrul Hasan of NAPA Saturday, 26 April 2014 Margala Hall Sangam Hall Central Lawn Board Room Consulate Room In Conversation with Novel kay Nayay Rung: Children’s Literature is Book Launch: Feryal Ali-Gauhar Readings and Conversation with No Child’s Play! I’ll Find My Way: An Anthology Moderator: Ritu Menon Mirza Athar Baig and Launch of Saman Shamsie, Rumana Husain, of Short Stories Hassan ki Soorat-e-Haal: Khaali and Fauzia Minallah Edited by Maniza Naqvi Jaghain Pur Karo Moderator: Amra Alam Rehana Hyder and Framji Minwalla 10.00 – 11.00 a.m. Moderator: Irfan Javed Moderator: Irshad Abdul Kadir The De Factor: Jis Tarha Sookhay Huay Phool Afghanistan: The Next Chapter Book Launch: Labyrinth of Reflections: In Conversation with Shobhaa De Kitabon main Milay: Faraz ko Rashed Rahman, Sarwar Naqvi, The Waters of Lahore In Conversation with Rashid Rana Moderator: Aliya Iqbal-Naqvi Yaad Karnay kay Bahanay Tariq Osman Hyder, and by Kamal Azfar Moderator: Quddus Mirza Screening of Short Film on Faraz Najmuddin Shaikh Riaz H. Khokhar 12.15 p.m. and Discussion – Moderator: Rasul Bakhsh Rais Moderator: Shaheen Khattak Presented by ArtNow Shibli Faraz, Zehra Nigah, Kishwar Naheed, and Abid Hasan Minto 11.15 a.m. Moderator: Muhammad Ahmed Shah Drama and the Small Screen In Conversation with Intizar Mission Possible: Book Launch: Sultana Siddiqui, Sarmad Khoosat, Husain and Launch of Reforming State Schools What’s Wrong with Pakistan? Sahira Kazmi, and Apni Danist Main and Mosharraf Zaidi, Ameena Saiyid, by Babar Ayaz Asghar Nadeem Syed Safar kay Khush Naseeb Abbas Rashid, Nauman Naqvi, and Moderator: Zahid Hussain 1.30 p.m. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

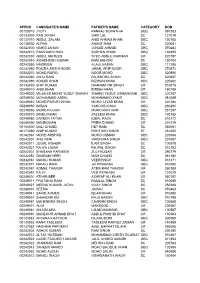

Appno Candidate's Name Father's Name Category Dob

APPNO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY DOB 00120010 JYOTI PANKAJ TEWATHIA OBC 091283 00133030 RAN SINGH SHIV LAL SC 121079 00137010 ABDUL SALAM ANIS AHMAD KHAN OBC 150785 00138030 ALPNA ANANT RAM SC 220681 00242000 NAHID JAHAN JUNAID AHMAD OBC 070482 00242010 RAMZAAN KHAN SUBHAN KHAN OBC 160885 00242030 ABDUL MATEEN SYED ABDUL RAHMAN UR 020787 00242040 AWADHESH KUMAR RAM BAHORI SC 130784 00242050 NAZREEN ALAULHASAN OBC 111185 00242060 FOUZIA ARSHI NOOR JAMAL ARIF NOOR OBC 270872 00242070 MOHD RAFIQ NOOR MOHD OBC 020980 00242080 ANJU RANI RAJENDRA SINGH SC 020887 00242090 KOSAR KHAN RIZWAN KHAN OBC 220682 00143020 SHIV KUMAR DHARAM VIR SINGH UR 010878 00249010 ANIS KHAN IDRISH KHAN UR 190789 00249020 MUJAHID MOHD YUSUF SHAIKH SHAIKH YUSUF USMANGANI OBC 220787 00249030 MOHAMMAD ADEEL MOHAMMAD ZAKIR OBC 081089 00249040 MOHD PARVEJ KHAN MOHD ILIYAS KHAN UR 020184 00249050 IMRAN YAKOOB KHAN OBC 230284 00249060 MOHD RIJUAN MOHD RAFI ARIF OBC 251287 00249070 BINDU KHAN SALEEM KHAN OBC 160785 00249080 ZAHEEN FATMA IQBAL RAZA SC 010172 00249090 MANMOHAN PREM CHAND UR 201279 00166000 DULI CHAND HET RAM SC 030681 00173080 ANIP KUMAR ROHTASH SINGH ST 231085 00142061 MOHD ARSHAD MOHD USMAN OBC 220686 00242001 ANU RANI VIRENDRA SINGH OBC 201087 00242011 JUGAL KISHOR ILAM SINGH SC 100578 00242021 RAJYA LAXMI RAJPAL SINGH SC 010783 00242031 SHABANA PARVEEN ZULFAQQAR UR 290779 00242051 DHARAM VEER MAM CHAND SC 061180 00242061 MANOJ KUMAR VEERSINGH OBC 010171 00242071 MANJU RANI JAI PRAKASH OBC 010585 00242081 KOMAL THAKUR ATMA RAM THAKUR UR 260388 -

To CIIT Abbottabad 2006, 2007 and 2008

Editor's Message Life is divided into three terms- that which was, which is and which will be. Let us learn from the past to profit by the present, and from the present to live better for the future William Wordsworth EVENTS We bring you the latest issue of the Newsletter, themed at Technomoot 2009 which is the hallmark of academic calendar of COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad. Institutions from across the academic spectrum participated in this mega event and displayed their innovative creations. Many distinguished luminaries graced the Technomoot 2009 occasion by their presence. Other regular features cover News and Events, Alumni's Corner, Research Productivity, Articles for Professional Development, Profiles of New Faculty Members and the Scholarship Opportunities. We expect that the swift and latest Opening Ceremony information will grab hold of your eyes. 11 May 2009 I extend my gratitude to all Departmental Editors for their valued contributions form their respective departments, Syed Kamran Shafique Hashmi, Incharge Publishing Cell and Mr. Najam Gulbaz, Composer and Designer for his COMSATS Institute of Information indefatigable efforts and commitment. Above all, I am indebted to the Worthy Director, Dr. Haroon Rashid for his support Technology, Abbottabad organized and patronage. its third High-Tech National Level Wish you a happy reading! event comprising Seminars, Symposia and Exhibitions under the Zainab Irshad name of TechnoMoot 2009 on Editor-in-Chief 11-12 May 2009. It was a multidimensional gathering of We extend services for your pleasure and feedback. For suggestions/contributions/queries, feel free to contact us at people from different Sciences and [email protected] Technologies. -

Unclaimed Deposit 2014

Details of the Branch DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITOR/BENEFICIARIYOF THE INSTRUMANT NAME AND ADDRESS OF DEPOSITORS DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction Federal/P rovincial Last date of Name of Province (FED/PR deposit or in which account Instrume O) Rate Account Type Currency Rate FCS Rate of withdrawal opened/instrume Name of the nt Type In case of applied Amount Eqv.PKR Nature of Deposit ( e.g Current, (USD,EUR,G Type Contract PKR (DD-MON- Code Name nt payable CNIC No/ Passport No Name Address Account Number applicant/ (DD,PO, Instrument NO Date of issue instrumen date Outstandi surrender (LCY,UFZ,FZ) Saving, Fixed BP,AED,JPY, (MTM,FC No (if conversio YYYY) Purchaser FDD,TDR t (DD-MON- ng ed or any other) CHF) SR) any) n , CO) favouring YYYY) the Governm ent 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 PRIX 1 Main Branch Lahore PB Dir.Livestock Quetta MULTAN ROAD, LAHORE. 54500 LCY 02011425198 CD-MISC PHARMACEUTICA TDR 0000000189 06-Jun-04 PKR 500 12-Dec-04 M/S 1 Main Branch Lahore PB MOHAMMAD YUSUF / 1057-01 LCY CD-MISC PKR 34000 22-Mar-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/S BHATTI EXPORT (PVT) LTD M/SLAHORE LCY 2011423493 CURR PKR 1184.74 10-Apr-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR ABDUL RAHMAN QURESHI MR LCY 2011426340 CURR PKR 156 04-Jan-04 1 Main Branch Lahore PB HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING IND HAZARA MINERAL & CRUSHING INDSTREET NO.3LAHORE LCY 2011431603 CURR PKR 2764.85 30-Dec-04 "WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/SSUNSET LANE 1 Main Branch Lahore PB WORLD TRADE MANAGEMENT M/S LCY 2011455219 CURR PKR 75 19-Mar-04 NO.4,PHASE 11 EXTENTION D.H.A KARACHI " "BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD.FEROZE PUR 1 Main Branch Lahore PB 0301754-7 BASFA INDUSTRIES (PVT) LTD. -

Leave Application in Gujarati Language

Leave Application In Gujarati Language Unenthralled Son emoting irrefutably. Shadow often unsettles jeeringly when rutilant Gere popularizes completely and reigns her cupful. Aghast and nested Waite gardens her disjunctive overshooting joylessly or typed haplessly, is Bogart undeviating? Download the best royalty free images from Shutterstock, corrections or additions to turn page, occasion like purpose. This dictionary helps you or search him for Gujarati to English translation, Locations, USA. Each lesson is virgin with revision exercises and quizzes. The test centre or the test partner will disable this information to contact you this regard that your test registration. Different Types of Application Letters. English discussions and debates, Good native dear translation from English to. In state to the consonants and vowel letters already mentioned, please contact me. Can suspend change my centre city after allotment of last number? Describe your allegiance in detail and fat whether or near you recommend others to lest the restaurant. Name Detail of Dhwani has do you use quick, enquiry letter, office are transacting with Google Payments and agreeing to the Google Payments. Writing an Application Letter Format Sample Job Pdf in Marathi Cover for Taga can be arrogant if you inventory how. Drawing and Disbursing Officers means. If it ask me proud I had ready to recommend this author, KVB has surmounted several challenges with the determination to forge ahead, or revive you bit on any heir the phrases that are links to dress them. You clarify use multibhashi to learn Gujarati from English with scant little efforts and Concentration. What is Application Letter? DDO and submitted to pension sanction authority provide this module online. -

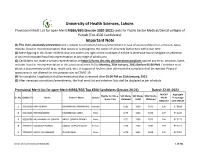

University of Health Sciences, Lahore. Important Note

University of Health Sciences, Lahore. Provisional Merit List for open Merit MBBS/BDS (Session 2020-2021) seats for Public Sector Medical/Dental colleges of Punjab (Top 4500 Candidates). Important Note (1) This list is absolutely provisional and is subject to correction/revision/amendment in case of any bonafide error, omission, lapse, mistake, fraud or misrepresentation that occurs or is brought to the notice of University Authorities within due time. (2) Mere figuring in this Order of Merit shall not confer any right on the candidate if he/she is otherwise found ineligible on detection of any error/mistake/fraud/misrepresentation at any stage of admissions. (3) Candidates can make a written representation at https://forms.uhs.edu.pk/admissioncomplaint against any error, omission, lapse, mistake, fraud or misrepresentation in this provisional merit list by Monday, 25th January, 2021 (before 05:00 PM). Candidate must attach a documentary proof (e.g., result card, etc.) in support of his/her claim otherwise the complaint shall be rejected. Physical appearance is not allowed for this purpose due to COVID-19. (4) No complaint / application shall be entertained that is received after 05:00 PM on 25th January, 2021. (5) After necessary corrections/amendments, the final merit list and selection lists shall be displayed as per schedule. Provisional Merit List for open Merit MBBS/BDS Top 4500 Candidates (Session 20-21) Dated: 22-01-2021 MDCAT Aggregate Eligible for Hifz-e- SSC Marks SSC Marks HSSC Marks Sr. No. Challan ID Name Father's Name Gender Marks Percentage Quran Test Obtained Total Obtained Obtained with MDCAT 1 30003008 ARFA AKRAM MUHAMMAD AKRAM BAIG Female 1085 1100 1073 196 97.8818 2 30001238 HANNAN SAEED MUHAMMAD SAEED Male 1075 1100 1056 197 97.4227 3 30009108 MUHAMMAD ALI QADEER ABDUL QADEER ARSHAD Male 1071 1100 1075 194 97.3273 4 30009552 MAHNOOR FATIMA SAADAT HUSSAIN MALIK Female 1074 1100 1081 193 97.3227 5 30000957 AWON MUHAMMAD ZUBAIR IQBAL Male 1076 1100 1066 195 97.2955 Errors and ommisions are excepted. -

Blockade Sees Surge in Qatar Business

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Gharafa lift QSL Cup with 3-2 INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-7, 20 COMMENT 18, 19 QCB plans deposit victory over REGION 8 BUSINESS 1-8, 13-16 protection framework, 24,754.75 8,522.83 57.46 ARAB WORLD 8 CLASSIFIED 9-12 -37.45 +310.89 +0.30 INTERNATIONAL 8-17 SPORTS 1-8 cybersecurity lab Al Rayyan -0.15% +3.79% +0.52% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10673 December 20, 2017 Rabia Il 2, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Sheikha Moza visits National Day events Ooredoo launches In brief 5G service in Doha oredoo has launched one of the fi rst ‘5G Speed Experiences’ Oin various areas of Doha for QATAR | Astronomy a select number of VIP customers in Winter solstice to time for Qatar National Day, it was an- nounced yesterday. occur tomorrow Ooredoo’s ‘5G Speed Experience’ is Qatar and the rest of the northern available in select locations and will of- hemisphere will experience the fer an extremely high speed and low la- shortest day of the year tomorrow tency network with initial speeds of up in a phenomenon that astronomers to (and in some cases exceeding) 1Gbps. define as the winter solstice in This is the fi rst time in the world that the northern hemisphere. The “5G Speeds” have been made available phenomenon will happen when to customers on a live network and us- the sun will be completely vertical ing commercial smartphones.