Daily Drawing and Writing Activities in a Preschool Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valley Champs

APRIL 2016 VALLEY CHAMPS Fresno Unified captured Valley titles in boys soccer and boys bas- ketball in February, historic wins that reflect the district’s investment in activities outside the classroom for all students. On Feb. 26, the McLane High School boys soccer team won the Central Section Division-IV title -- its first Valley championship -- at McLane Stadi- um with a 5-3 overtime win against Kerman High School. McLane scored two goals in the second overtime. The team, led by head coach Ramiro Teran and assistant coach Edgar Mondragon, won Students the North Yosemite League title with a 9-0-1 record, its first league title since 1979. Below, from left, Juan Flores, Emerson Hernandez Spellbound and Gabriel Sosa celebrate after winning the title. The Roosevelt High School boys basketball team, seeking its first {PAGE 5} Valley crown since 1977, brought the title home on March 5 with a 60-36 win over Selma High School for the D-III championship at Selland Arena. The Rough Riders, with a record of 25-7, were led by the Fresno State-bound Bryson Williams (left) who had 29 points, 23 rebounds and two blocks. Second-year head coach is Jamarr Chisom. See story on individual Valley champs on Page 5. Employee Spotlight {PAGE 6} Help Prioritize $26M in School Site Funds Parents and community members who how state and federal funding should be site councils must generally allocate want to be more involved in the inner used. School site councils districtwide additional LCFF funding to categories workings of their neighborhood school helped allocate $21.2 million in Local such as instructional supports, teacher Preschool should look no further than participat- Control Funding Formula (LCFF) professional learning, family engage- ing in a school site council -- made funds for the current school year. -

Annual Report 2009

Annual Report 2009 Contents Letter to the Shareholders 3 Report on Operations 6 Key Operating and Financial Data - Telecom Italia Group 7 Corporate Boards at December 31, 2009 13 Macro-Organization Chart at December 31, 2009 - Telecom Italia Group 14 Information for Investors 15 Review of Operating and Financial Performance - Telecom Italia Group 20 Events Subsequent to December 31, 2009 36 Business Outlook for the Year 2010 36 Consolidated Financial Statements - Telecom Italia Group 38 Highlights - The Business Units of the Telecom Italia Group 44 The Business Units of the Telecom Italia Group 46 Domestic 46 Brazil 61 Media 65 Olivetti 69 International Investments 72 Discontinued Operations/Non-Current Assets Held for Sale 75 Review of Operating and Financial Performance - Telecom Italia S.p.A. 78 Financial Statements - Telecom Italia S.p.A. 87 Reconciliation of Consolidated Equity 92 Related Party Transactions 93 Sustainability Section 94 Customers 98 Suppliers 100 Competitors 101 Institutions 102 The Environment 103 The Community 111 - Research and Development 111 Human Resources 113 Shareholders 122 Alternative Performance Measures 124 Equity Investments Held by Directors, Statutory Auditors, General Managers and Key Managers 126 Glossary 127 Telecom Italia Group Consolidated Financial Statements at December 31, 2009 136 Contents 137 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 139 Separate Consolidated Income Statements 141 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 142 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 143 Consolidated Cash Flow Statements 144 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 146 Certification of the Consolidated Financial Statements pursuant to art. 81-ter of Consob Regulation 11971 dated May 14, 1999, with Amendments and Additions 285 Independent Auditors’ Report 286 Telecom Italia S.p.A. -

995 Final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels,23.9.2010 SEC(2010)995final COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod2007-2008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) COM(2010)450final EN EN COMMISSIONSTAFFWORKINGDOCUMENT Accompanyingdocumenttothe COMMUNICATIONFROMTHECOMMISSIONTOTHE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT,THECOUNCIL,THEEUROPEANECONOMIC ANDSOCIAL COMMITTEEANDTHECOMMITTEEOFTHEREGIONS NinthCommunication ontheapplicationofArticles4and5ofDirective89/552/EECas amendedbyDirective97/36/ECandDirective2007/65/EC,fortheperiod20072008 (PromotionofEuropeanandindependentaudiovisual works) EN 2 EN TABLE OF CONTENTS ApplicationofArticles 4and5ineachMemberState ..........................................................5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 1. ApplicationofArticles 4and5:generalremarks ...................................................5 1.1. MonitoringmethodsintheMemberStates ..................................................................6 1.2. Reasonsfornon-compliance ........................................................................................7 1.3. Measures plannedor adoptedtoremedycasesofnoncompliance .............................8 1.4. Conclusions -

TV-Programme Zur Erfassung GT 1 Per 1.1.2015

TV-Programme zur Erfassung GT 1 per 1.1.2015 Sender- Kurz- Spra- Land Vollständige Bezeichnung ID bezeichnung che Schweiz 11 CH SRF1 SCHWEIZER FERNSEHEN - DRS 1 de 206 CH SRFzwei SRF zwei de 52 CH RTSun TELEVISION SUISSE ROMANDE 1 fr 51 CH RSILA1 RADIOTELEVISIONE SVIZZERA ITALIANA 1 it 207 CH RSILA2 RADIOTELEVISIONE SVIZZERA ITALIANA 2 it 242 CH SRFInfo SRF Info de 836 CH 3+ 3plus de 310 CH Star STAR TV de 208 CH RTSdeux TELEVISION SUISSE ROMANDE 2 fr 1352 CH 4+ 4plus de 1306 CH joiz joiz de 301 CH TZüri TELE ZüRI de 320 CH TTOP TELE TOP - WINTERTHUR de 302 CH TEM1 TELE M1 de 308 CH Tele1 TELE 1 de 307 CH TBärn TELE BAERN de 1134 CH SSF Schweizer Sport Fernsehen de 306 CH TBasl TELE BASEL de 177 CH TVM3 3ème chaîne romande fr 303 CH Cana9 CANAL 9 - SIERRE fr 309 CH,FR CAAL+ CANAL ALPHA + fr 229 CH VIVA VIVA Schweiz de 311 CH LéMan LEMAN BLEU fr 322 CH TOST TELE OSTSCHWEIZ - ST. GALLEN de 1276 CH latélé la télé fr 321 CH TETI TELE TICINO it 317 CH TBiel TELE BIELINGUE - BIEL/BIENNE de 492 CH zürip züriplus de 323 CH TSüdO TELE SÜDOSTSCHWEIZ - CHUR de 1213 CH RouTV Rouge TV de 1432 CH NRJTV Energy TV de 253 CH S5 Schweiz 5 de 319 CH SHf SCHAFFHAUSER LOKAL-TV de 318 CH TRhta TELE RHEINTAL de 1257 CH KAN9 Kanal 9 / Canal 9 de 194 CH maxtv max tv de 1370 CH CHTV CHTV (CH Television GmbH) de 193 CH TNapf Tele Napf de 1254 CH ALPEN Alpen Welle TV de 1433 CH TCFlashD TC Flash D de 1434 CH TCFlashF TC Flash F fr 1072 CH NZeit Die Neue Zeit TV de 196 CH TeleD Tele D de 314 CH Alf AROLFINGER LOKALFERNSEHEN AARAU-ZOFINGEN de 1395 CH TORTele TOR Télévision -

The Role of a Chief Executive Officer

The Role of a Chief Executive Officer An extended look into the role & responsibilities of a CRO Provided by: Contents 1 Chief Revenue Officer Role within the Corporate Hierarchy 1 1.1 Chief revenue officer ......................................... 1 1.1.1 Roles and functions ...................................... 1 1.1.2 The CRO profile ....................................... 1 1.1.3 References .......................................... 2 1.2 Corporate title ............................................. 2 1.2.1 Variations ........................................... 2 1.2.2 Corporate titles ........................................ 4 1.2.3 See also ............................................ 8 1.2.4 References .......................................... 9 1.2.5 External links ......................................... 9 1.3 Senior management .......................................... 9 1.3.1 Positions ........................................... 10 1.3.2 See also ............................................ 11 1.3.3 References .......................................... 11 2 Areas of Responsibility 12 2.1 Revenue ................................................ 12 2.1.1 Business revenue ....................................... 12 2.1.2 Government revenue ..................................... 13 2.1.3 Association non-dues revenue ................................. 13 2.1.4 See also ............................................ 13 2.1.5 References .......................................... 13 2.2 Revenue management ........................................ -

Corpus Antville

Corpus Epistemológico da Investigação Vídeos musicais referenciados pela comunidade Antville entre Junho de 2006 e Junho de 2011 no blogue homónimo www.videos.antville.org Data Título do post 01‐06‐2006 videos at multiple speeds? 01‐06‐2006 music videos based on cars? 01‐06‐2006 can anyone tell me videos with machine guns? 01‐06‐2006 Muse "Supermassive Black Hole" (Dir: Floria Sigismondi) 01‐06‐2006 Skye ‐ "What's Wrong With Me" 01‐06‐2006 Madison "Radiate". Directed by Erin Levendorf 01‐06‐2006 PANASONIC “SHARE THE AIR†VIDEO CONTEST 01‐06‐2006 Number of times 'panasonic' mentioned in last post 01‐06‐2006 Please Panasonic 01‐06‐2006 Paul Oakenfold "FASTER KILL FASTER PUSSYCAT" : Dir. Jake Nava 01‐06‐2006 Presets "Down Down Down" : Dir. Presets + Kim Greenway 01‐06‐2006 Lansing‐Dreiden "A Line You Can Cross" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 SnowPatrol "You're All I Have" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 Wolfmother "White Unicorn" : Dir. Kris Moyes? 01‐06‐2006 Fiona Apple ‐ Across The Universe ‐ Director ‐ Paul Thomas Anderson. 02‐06‐2006 Ayumi Hamasaki ‐ Real Me ‐ Director: Ukon Kamimura 02‐06‐2006 They Might Be Giants ‐ "Dallas" d. Asterisk 02‐06‐2006 Bersuit Vergarabat "Sencillamente" 02‐06‐2006 Lily Allen ‐ LDN (epk promo) directed by Ben & Greg 02‐06‐2006 Jamie T 'Sheila' directed by Nima Nourizadeh 02‐06‐2006 Farben Lehre ''Terrorystan'', Director: Marek Gluziñski 02‐06‐2006 Chris And The Other Girls ‐ Lullaby (director: Christian Pitschl, camera: Federico Salvalaio) 02‐06‐2006 Megan Mullins ''Ain't What It Used To Be'' 02‐06‐2006 Mr. -

Manual on Statistics of International Trade in Services

UK Data Archive Study Number 6711 - International Trade in Services: Secure Access Economic & Social Affairs Manual on Statistics of international trade in services United Nations European Commission International Monetary Fund Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World Trade Organization asdf United Nations ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/86 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS STATISTICS DIVISION STATISTICAL PAPERS SERIES M NO. 86 MANUAL on STATISTICS of INTERNATIONAL TRADE in SERVICES United Nations European Commission International Monetary Fund Organisation for Economic United Nations Conference World Trade Organization Co-operation and on Trade and Development Development Geneva, Luxembourg, New York, Paris, Washington, D.C., 2002 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/86 International Monetary Fund Publication Stock No. MSITEA ISBN 1-58906-128-4 United Nations publication Sales No. E.02.XVII.11 ISBN 92-1-161448-1 Inquiries should be directed to: United Nations Publications DC2-853 New York, NY 10017 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2002 United Nations, European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and World Trade Organization All rights reserved Foreword The Manual on Statistics of International Trade in Services has been developed and published jointly by our six organizations, managed through the mechanism of an inter-agency task force. The Manual sets out an internationally agreed framework for the compilation and reporting of statistics of international trade in services in a broad sense. -

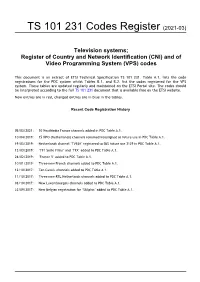

TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03)

TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03) Television systems; Register of Country and Network Identification (CNI) and of Video Programming System (VPS) codes This document is an extract of ETSI Technical Specification TS 101 231. Table A.1. lists the code registrations for the PDC system whilst Tables B.1. and B.2. list the codes registered for the VPS system. These tables are updated regularly and maintained on the ETSI Portal site. The codes should be interpreted according to the full TS 101 231 document that is available free on the ETSI website. New entries are in red, changed entries are in blue in the tables. Recent Code Registration History 05/03/2021: 10 NextMedia France channels added in PDC Table A.1. 10/04/2019: 15 NPO (Netherlands) channels renamed/reassigned as future use in PDC Table A.1. 19/03/2019: Netherlands channel ’TV538’ registered to SBS future use 3129 in PDC Table A.1. 13/03/2019: ‘TF1 Serie Films’ and ‘TFX’ added to PDC Table A.1. 26/02/2019: ‘France 5’ added to PDC Table A.1. 10/01/2019: Three new French channels added to PDC Table A.1. 12/10/2017: Ten Canal+ channels added to PDC Table A.1. 11/10/2017: Three new RTL Netherlands channels added to PDC Table A.1. 03/10/2017: New Luxembourgois channels added to PDC Table A.1. 22/09/2017: New Belgian registration for ‘SBSplus’ added to PDC Table A.1. 2 TS 101 231 Codes Register (2021-03) Annex A (informative): Register of CNI codes for Teletext based systems Table A.1: Register of Country and Network Identification (CNI) codes for Teletext based systems 8/30 8/ 30 X/ -

Universidade Federal Da Bahia Instituto De Humanidades, Artes E Ciências Programa Multidisciplinar De Pós-Graduação Em Cultura E Sociedade

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ARQUEOLOGIA DA MÍDIA NA ERA PÓS-MÍDIA: O ‘NASCIMENTO’ E A ‘MORTE’ DO CINEMA por PEDRO MARQUES DELL’ORTO Orientador(a): Prof(a). Dr(a). KARLA SCHUCH BRUNET SALVADOR, 2016 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ARQUEOLOGIA DA MÍDIA NA ERA PÓS-MÍDIA: O ‘NASCIMENTO’ E A ‘MORTE’ DO CINEMA por PEDRO MARQUES DELL’ORTO Orientador(a): Prof. Dr. KARLA SCHUCH BRUNET Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-Graduação em Cultura e Sociedade do Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de Mestre. SALVADOR, 2016 Sistema de Bibliotecas da UFBA Dell’Orto, Pedro Marques. Arqueologia da mídia na era pós-mídia: o ‘nascimento’ e a ‘morte’ do cinema / por Pedro Marques Dell’Orto. - 2016. 197 f.: il. Inclui anexo. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Karla Schuch Brunet. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências Professor Milton Santos, Salvador, 2016. 1. Cinema. 2. Mídia digital. 3. Arqueologia. 4. Tecnologia. 5. Cibernética. 6. Arte. I. Brunet, Karla Schuch. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências Professor Milton Santos. III. Título. CDD - 791.43 CDU - 791.43 Agradecimentos À minha família, especialmente meus pais, Leonardo Dell’Orto e Silvia Dell’Orto, meus irmãos, Julia Dell’Orto e Caio Dell’Orto; minha tia Eleonora Dell’Orto, por me incentivar e me mostrar diferentes mundos; e minha tia Silvania Marques, por compartilhar seus conhecimentos sobre a natureza. -

Sec(2008) 2310

EN EN EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 22.7.2008 SEC(2008) 2310 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Accompanying document to the COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS Eighth Communication on the application of Articles 4 and 5 of Directive 89/552/EEC ‘Television without Frontiers’, as amended by Directive 97/36/EC, for the period 2005- 2006 [COM(2008) 481 final] EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 1: Performance indicators...................................................... 3 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 2: Charts and tables on the application of Articles 4 and 5... 6 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 3: Application of Articles 4 and 5 in each Member State ... 12 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 4: Summary of the reports from the Member States ........... 44 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 5: Voluntary reports by Bulgaria and Romania................. 177 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 6: Reports from the Member States of the European Free Trade Association participating in the European Economic Area ......................................... 182 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 7: Average transmission time of European works by channels with an audience share above 3% .. ........................................................................ 187 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 8: List of television channels in the Member States which failed to achieve the majority proportion required by Article 4............................................. 195 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 9: List of television channels in the Member States which failed to achieve the minimum proportion required by Article 5........................................... 213 EN 2 EN BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 1: Performance indicators The following indicators facilitate the evaluation of compliance with the proportions referred to in Article 4 and 5 of the Directive. Indicators 2 – 5 are based on criteria set out in Articles 4 and 5. -

2004-03-21 Po

Gallery owner uses background to help homeowners - Local news, page A3 Your hometown newspaper serving Plymouth and Got milk? Plymouth Township for 118 years’ Are kids PLYMOUTH drinking too much pop and not enough March 21 2004 milk? 75 cents Health, C6 V o l u m e 118 N u m b e r 6 0 wiviv.hom etow idife.com © 2 0 0 4 H o m e t o w n C ommunications N e t w o r k Win a $500 Farmer Jack shopping spree Layoffs loom as district eyes See page B3 for details BY TONY BRUSCATO require a 90-day notice There are possi at Canton High School earns $98,021, tion, Mark Bretton m the curriculum cen STAFF WRITER bilities that some, if not all, could be Tom Willette at Salem and Terry Sawchuk ter, Mike Wesner, a computer technician, retained However, Ryan said its likely at Plymouth each earn $83,395 and Susan Jackiw, an executive secretary The Plymouth-Canton Schools Board of there will be a restructuring of the athletic Ryan said some of those laid off could Ryan said he expects to give approxi Education will consider the layoffs of hierarchy at the park be back at reduced salaries mately 23 teachers, the same as last year, seven administrators, including the three “We can save money by restructuring ‘We have to find a way to change the layoff notices next month By law, teach athletic directors at Plymouth-Canton the athletic leadership,’ said Ryan “I’ve costs,” he said “By restructuring the ers must have notice of layoffs 60 days Educational Park, as part of a cost-saving talked to Troy, Livonia, Farmington and department, they could be back -

VIACOM INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2007 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-32686 VIACOM INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 20-3515052 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 1515 Broadway New York, NY 10036 (212) 258-6000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 6.85% Senior Notes due 2055 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title Of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.