Snowbank Fungi Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clitocybe Sclerotoidea a Most Wonderful Parasite of Helvella Vespertina

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • March 2013, vol. 64:07 March 19 MycoDigest: General Meeting Speaker Clitocybe Sclerotoidea A Most Wonderful Parasite of Helvella Vespertina Nhu Nguyen love parasites. They are just some of the neatest things; except when I’m forced to play host. Parasites come in all sorts of shapes and sizes and it is thought that Ievery species on earth has a parasite of some sort. Animals have parasites, plants have parasites, and fungi too have parasites. I can talk about parasites all day (yes, that parasitology class in college right before lunch three times a week left quite the impression), but I will focus on just one this time. Mycoparasites are fungi that parasitize other fungi and they commonly occur in the mushroom world. Typically the more colorful or pronounced ones get more noticed. Examples of col- orful parasites would be Hypomyces chrysosporium, a common parasite on boletes on the west coast with golden Nhu Nguyen spores. Another one known amongst “Yeasts in the Gut of Beetles –Minute mushroom hunters is Hypomyces lac- Fungi That Cheer and Fuel the World” tifluorum that covers a Russula, turn- hu Nguyen is a PhD candidate ing it beautifully orange and deli- at UC Berkeley. He is studying a cious. Then you have those that are Nfungal-bacterial symbiosis system for A closeup of a large cap of Clitocybe sclerotoi- tiny, but still beautiful like Dendro- his PhD dissertation in the Bruns Lab deum with smaller mushrooms coming out of collybia racemosa with its strange side where lots of fun things happen. -

Appendix K. Survey and Manage Species Persistence Evaluation

Appendix K. Survey and Manage Species Persistence Evaluation Establishment of the 95-foot wide construction corridor and TEWAs would likely remove individuals of H. caeruleus and modify microclimate conditions around individuals that are not removed. The removal of forests and host trees and disturbance to soil could negatively affect H. caeruleus in adjacent areas by removing its habitat, disturbing the roots of host trees, and affecting its mycorrhizal association with the trees, potentially affecting site persistence. Restored portions of the corridor and TEWAs would be dominated by early seral vegetation for approximately 30 years, which would result in long-term changes to habitat conditions. A 30-foot wide portion of the corridor would be maintained in low-growing vegetation for pipeline maintenance and would not provide habitat for the species during the life of the project. Hygrophorus caeruleus is not likely to persist at one of the sites in the project area because of the extent of impacts and the proximity of the recorded observation to the corridor. Hygrophorus caeruleus is likely to persist at the remaining three sites in the project area (MP 168.8 and MP 172.4 (north), and MP 172.5-172.7) because the majority of observations within the sites are more than 90 feet from the corridor, where direct effects are not anticipated and indirect effects are unlikely. The site at MP 168.8 is in a forested area on an east-facing slope, and a paved road occurs through the southeast part of the site. Four out of five observations are more than 90 feet southwest of the corridor and are not likely to be directly or indirectly affected by the PCGP Project based on the distance from the corridor, extent of forests surrounding the observations, and proximity to an existing open corridor (the road), indicating the species is likely resilient to edge- related effects at the site. -

Major Clades of Agaricales: a Multilocus Phylogenetic Overview

Mycologia, 98(6), 2006, pp. 982–995. # 2006 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview P. Brandon Matheny1 Duur K. Aanen Judd M. Curtis Laboratory of Genetics, Arboretumlaan 4, 6703 BD, Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Wageningen, The Netherlands Worcester, Massachusetts, 01610 Matthew DeNitis Vale´rie Hofstetter 127 Harrington Way, Worcester, Massachusetts 01604 Department of Biology, Box 90338, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 Graciela M. Daniele Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biologı´a Vegetal, M. Catherine Aime CONICET-Universidad Nacional de Co´rdoba, Casilla USDA-ARS, Systematic Botany and Mycology de Correo 495, 5000 Co´rdoba, Argentina Laboratory, Room 304, Building 011A, 10300 Baltimore Avenue, Beltsville, Maryland 20705-2350 Dennis E. Desjardin Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, Jean-Marc Moncalvo San Francisco, California 94132 Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Royal Ontario Museum and Department of Botany, University Bradley R. Kropp of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6 Canada Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322 Zai-Wei Ge Zhu-Liang Yang Lorelei L. Norvell Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Pacific Northwest Mycology Service, 6720 NW Skyline Sciences, Kunming 650204, P.R. China Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97229-1309 Jason C. Slot Andrew Parker Biology Department, Clark University, 950 Main Street, 127 Raven Way, Metaline Falls, Washington 99153- Worcester, Massachusetts, 01609 9720 Joseph F. Ammirati Else C. Vellinga University of Washington, Biology Department, Box Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3102 Timothy J. -

Spore Prints

SPORE PRINTS BULLETIN OF THE PUGET SOUND MYCOLOGICAL SOCIETY Number 473 June 2011 OLDEST, ODDEST FUNGI FINALLY “The big message here is that most fungi and most fungal diversity PHOTOGRAPHED Susan Milius reside in fungi that have neither been collected nor cultivated,” Science News, May 12, 2011 says John W. Taylor of the University of California, Berkeley. Exeter team member Meredith Jones spotted the hard-to-detect organisms by marking them with fluorescent tags. The trick re- vealed fungal cells attached to algal cells as if parasitizing them. M. Jones One of the big questions about early fungi is whether they might have arisen from “some kind of parasitic ancestor like Rozella,” says Rytas Vilgalys of Duke University. Interesting, yes. But loosening the definition of fungi to include organisms without chitin walls could wreak havoc in the concept of that group, objects Robert Lücking of the Field Museum in Chicago. “I would actually conclude, based on the evidence, that these are not fungi,” he says. Instead, they might be near rela- tives—an almost-fungus. Two fungal cells, possibly from an ancient lineage, each show a curvy, taillike flagellum (red) during a mobile stage in their life cycle. IS MUTATED FUNGUS KILLING AMERICAN BATS? Andy Coghlan Images of little dots, some wriggling a skinny tail, give scientists New Scientist, May 24, 2011 a first glimpse of a vast swath of the oldest, and perhaps oddest, fungal group alive today. A fungus blamed for killing more than a mil- The first views suggest that, unlike any other fungi known, these lion bats in the US since 2006 has been found might live as essentially naked cells without the rigid cell wall to differ only slightly from an apparently that supposedly defines a fungus, says Tom Richards of the Natu- harmless European version. -

Species Recognition in Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Pluteaceae, Agaricales): Morphology, Geography and Phylogeny

Mycol Progress (2011) 10:453–479 DOI 10.1007/s11557-010-0716-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Species recognition in Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Pluteaceae, Agaricales): morphology, geography and phylogeny Alfredo Justo & Andrew M. Minnis & Stefano Ghignone & Nelson Menolli Jr. & Marina Capelari & Olivia Rodríguez & Ekaterina Malysheva & Marco Contu & Alfredo Vizzini Received: 17 September 2010 /Revised: 22 September 2010 /Accepted: 29 September 2010 /Published online: 20 October 2010 # German Mycological Society and Springer 2010 Abstract The phylogeny of several species-complexes of the P. fenzlii, P. phlebophorus)orwithout(P. ro me lli i) molecular genera Pluteus and Volvopluteus (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) differentiation in collections from different continents. A was investigated using molecular data (ITS) and the lectotype and a supporting epitype are designated for Pluteus consequences for taxonomy, nomenclature and morpho- cervinus, the type species of the genus. The name Pluteus logical species recognition in these groups were evaluated. chrysophlebius is accepted as the correct name for the Conflicts between morphological and molecular delimitation species in sect. Celluloderma, also known under the names were detected in sect. Pluteus, especially for taxa in the P.admirabilis and P. chrysophaeus. A lectotype is designated cervinus-petasatus clade with clamp-connections or white for the latter. Pluteus saupei and Pluteus heteromarginatus, basidiocarps. Some species of sect. Celluloderma are from the USA, P. castri, from Russia and Japan, and apparently widely distributed in Europe, North America Volvopluteus asiaticus, from Japan, are described as new. A and Asia, either with (P. aurantiorugosus, P. chrysophlebius, complete description and a new name, Pluteus losulus,are A. Justo (*) N. Menolli Jr. Biology Department, Clark University, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, 950 Main St., Rua Pedro Vicente 625, Worcester, MA 01610, USA São Paulo, SP 01109-010, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] O. -

Pezizales, Pyronemataceae), Is Described from Australia Pamela S

Swainsona 31: 17–26 (2017) © 2017 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium (Adelaide, South Australia) A new species of small black disc fungi, Smardaea australis (Pezizales, Pyronemataceae), is described from Australia Pamela S. Catcheside a,b, Samra Qaraghuli b & David E.A. Catcheside b a State Herbarium of South Australia, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Email: [email protected] b School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, PO Box 2100, Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: A new species, Smardaea australis P.S.Catches. & D.E.A.Catches. (Ascomycota, Pezizales, Pyronemataceae) is described and illustrated. This is the first record of the genus in Australia. The phylogeny of Smardaea and Marcelleina, genera of violaceous-black discomycetes having similar morphological traits, is discussed. Keywords: Fungi, discomycete, Pezizales, Smardaea, Marcelleina, Australia Introduction has dark coloured apothecia and globose ascospores, but differs morphologically from Smardaea in having Small black discomycetes are often difficult or impossible dark hairs on the excipulum. to identify on macro-morphological characters alone. Microscopic examination of receptacle and hymenial Marcelleina and Smardaea tissues has, until the relatively recent use of molecular Four genera of small black discomycetes with purple analysis, been the method of species and genus pigmentation, Greletia Donad., Pulparia P.Karst., determination. Marcelleina and Smardaea, had been separated by characters in part based on distribution of this Between 2001 and 2014 five collections of a small purple pigmentation, as well as on other microscopic black disc fungus with globose spores were made in characters. -

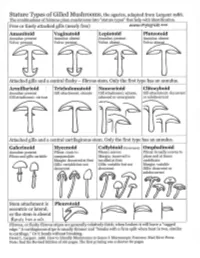

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Pt Reyes Species As of 12-1-2017 Abortiporus Biennis Agaricus

Pt Reyes Species as of 12-1-2017 Abortiporus biennis Agaricus augustus Agaricus bernardii Agaricus californicus Agaricus campestris Agaricus cupreobrunneus Agaricus diminutivus Agaricus hondensis Agaricus lilaceps Agaricus praeclaresquamosus Agaricus rutilescens Agaricus silvicola Agaricus subrutilescens Agaricus xanthodermus Agrocybe pediades Agrocybe praecox Alboleptonia sericella Aleuria aurantia Alnicola sp. Amanita aprica Amanita augusta Amanita breckonii Amanita calyptratoides Amanita constricta Amanita gemmata Amanita gemmata var. exannulata Amanita calyptraderma Amanita calyptraderma (white form) Amanita magniverrucata Amanita muscaria Amanita novinupta Amanita ocreata Amanita pachycolea Amanita pantherina Amanita phalloides Amanita porphyria Amanita protecta Amanita velosa Amanita smithiana Amaurodon sp. nova Amphinema byssoides gr. Annulohypoxylon thouarsianum Anthrocobia melaloma Antrodia heteromorpha Aphanobasidium pseudotsugae Armillaria gallica Armillaria mellea Armillaria nabsnona Arrhenia epichysium Pt Reyes Species as of 12-1-2017 Arrhenia retiruga Ascobolus sp. Ascocoryne sarcoides Astraeus hygrometricus Auricularia auricula Auriscalpium vulgare Baeospora myosura Balsamia cf. magnata Bisporella citrina Bjerkandera adusta Boidinia propinqua Bolbitius vitellinus Suillellus (Boletus) amygdalinus Rubroboleus (Boletus) eastwoodiae Boletus edulis Boletus fibrillosus Botryobasidium longisporum Botryobasidium sp. Botryobasidium vagum Bovista dermoxantha Bovista pila Bovista plumbea Bulgaria inquinans Byssocorticium californicum -

Project Cover Sheet

Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement Number: H1200040001 PROJECT COVER SHEET TITLE OF PROJECT: Investigation of Mycorrhizal fungi associated with whitebark pine in Waterton Lakes- Glacier National Parks Ecosystem. NAME OF PARK/NPS UNIT: Glacier NP NAME OF UNIVERSITY PARTNER: Montana State University NPS KEY OFFICIAL: Joyce Lapp Glacier National Park West Glacier, MT 59936 406-888-7817 [email protected] PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Cathy L. Cripps Department of Plant Sciences & Plant Pathology 119 Plant BioSciences Building Montana State University Bozeman, MT 59717 [email protected] 406-994-5226 COST OF PROJECT: Direct Cost: $ 1000.00 Indirect Cost (CESU overhead): $ 175.00 Total Cost: $ 1,175.00 NPS ACCOUNT NUMBER: 1430-7077-634 NAME OF FUND SOURCE: IMR-IMRICO PROJECT SCHEDULE, FINAL PRODUCTS, AND PAYMENTS Date of Project Initiation: May 1, 2007 List of Products: (1) Field collection of ectomycorrhizae from Whitebark pine and identification of this fungi, (2) final report due on March 31, 2008. Payment Schedule: Invoices as received from the University. End Date of Project: May 1, 2008 1 GLACIER NATIONAL PARK Investigation of Native Mycorrhizal Fungi with Whitebark Pine Final Report 2009 Cathy Cripps, Montana State University ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION Whitebark pine is a picturesque, long-lived tree of high mountain landscapes in much of the American West. It is a "keystone” species supplying food and shelter for wildlife and often holding the snow and rocky soils in places where other trees cannot grow. Now, however, in about half of its natural range, including Waterton-Glacier NP, whitebark pine is mostly dead or dying, due to an introduced blister rust disease and replacement by competing trees as a result of fire exclusion (Schwandt 2006, Tomback & Kendall 2001, Kendrick & Keane 2001). -

Preliminary Classification of Leotiomycetes

Mycosphere 10(1): 310–489 (2019) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes Ekanayaka AH1,2, Hyde KD1,2, Gentekaki E2,3, McKenzie EHC4, Zhao Q1,*, Bulgakov TS5, Camporesi E6,7 1Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China 2Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 3School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 4Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 5Russian Research Institute of Floriculture and Subtropical Crops, 2/28 Yana Fabritsiusa Street, Sochi 354002, Krasnodar region, Russia 6A.M.B. Gruppo Micologico Forlivese “Antonio Cicognani”, Via Roma 18, Forlì, Italy. 7A.M.B. Circolo Micologico “Giovanni Carini”, C.P. 314 Brescia, Italy. Ekanayaka AH, Hyde KD, Gentekaki E, McKenzie EHC, Zhao Q, Bulgakov TS, Camporesi E 2019 – Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes. Mycosphere 10(1), 310–489, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Abstract Leotiomycetes is regarded as the inoperculate class of discomycetes within the phylum Ascomycota. Taxa are mainly characterized by asci with a simple pore blueing in Melzer’s reagent, although some taxa have lost this character. The monophyly of this class has been verified in several recent molecular studies. However, circumscription of the orders, families and generic level delimitation are still unsettled. This paper provides a modified backbone tree for the class Leotiomycetes based on phylogenetic analysis of combined ITS, LSU, SSU, TEF, and RPB2 loci. In the phylogenetic analysis, Leotiomycetes separates into 19 clades, which can be recognized as orders and order-level clades. -

IL MONDO DEI FUNGHI Appunti Di Micologia

Maria Rosaria Tieri – Nino Tieri IL MONDO DEI FUNGHI appunti di micologia 1 Collana : “I quaderni della natura ” © Dispensa tratta da : FUNGHI D‟ABRUZZO Edizioni Paper's World S. Atto Teramo di Maria Rosaria Tieri e Nino Tieri FUNGHI IN CUCINA Edizioni Menabò di Maria Rosaria Tieri e Nino Tieri Con la preziosa collaborazione del prof. Mimmo Bernabeo Copertina di Nino Tieri © I diritti sono riservati. Il divieto di riproduzione è totale, anche a mezzo fotocopia e per uso interno. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione potrà essere riprodotta, archiviata in sistemi di ricerca o trasmessa in qualunque forma elettronica, meccanica, registrata o altro. 2 BREVE STORIA DELLA MICOLOGIA Le origini dei funghi sono di sicuro antichissime, di certo, i funghi, come organismi eucarioti, apparvero sulla terra più di 500 milioni di anni fa. La documentazione, circa la loro presenza, viene dedotta dai resti fossili venuti recente- mente alla luce, risalenti a moltissimi milioni di anni fa: nei resti del carbonifero (300 milioni di anni fa) sono, infatti, riconoscibili varietà di funghi ancora oggi presenti tra le specie della flora fungina. Le popolazioni primordiali, agli inizi della civiltà umana, hanno avuto sicuramente di- mestichezza con i funghi, sia per scopi alimentari che per pratiche religiose ed arti- stiche. Oggi non siamo a conoscenza del significato che i funghi rappresentavano per l‟uomo primitivo. Non è noto, infatti, se egli se ne nutrisse o se li ignorasse, né tanto- meno se fosse in grado di distinguere le specie eduli da quelle velenose. Tra gli oggetti ritrovati nello zaino dell‟uomo di Similaun, risalente a più di 5000 anni fa, vi erano anche funghi allucinogeni secchi. -

Funghi Campania

Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” Dipartimento di Arboricoltura, Botanica e Patologia vegetale I funghi della Campania Emmanuele Roca, Lello Capano, Fabrizio Marziano Coordinamento editoriale: Michele Bianco, Italo Santangelo Progetto grafico: Maurizio Cinque, Pasquale Ascione Testi: Emmanuele Roca, Lello Capano, Fabrizio Marziano Coordinamento fotografico: Lello Capano Collaborazione: Gennaro Casato Segreteria: Maria Raffaela Rizzo Iniziativa assunta nell’ambito del Progetto CRAA “Azioni integrate per lo sviluppo razionale della funghicol- tura in Campania”; Coordinatore scientifico Prof.ssa Marisa Di Matteo. Foto di copertina: Amanita phalloides (Fr.) Link A Umberto Violante (1937-2001) Micologo della Scuola Partenopea I funghi della Campania Indice Presentazione........................................................................................... pag. 7 Prefazione................................................................................................ pag. 9 1 Campania terra di funghi, cercatori e studiosi....................................... pag. 11 2 Elementi di biologia e morfologia.......................................................... pag. 23 3 Principi di classificazione e tecniche di determinazione....................... pag. 39 4 Elenco delle specie presenti in Campania.............................................. pag. 67 5 Schede descrittive delle principali specie.............................................. pag. 89 6 Glossario...............................................................................................