Newsletter 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

CONTENTS Xiii Xxxi Paid on Both Sides

CONTENTS PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi INTRODUCTION xiii THE TEXT OF THIS EDITION xxxi PLAYS Paid on Both Sides [first version] (1928), by Auden 3 Paid on Both Sides [second version] (1928), by Auden 14 The Enemies of a Bishop (1929), by Auden and Isherwood 35 The Dance of Death (1933), by Auden 81 The Chase (1934), by Auden 109 The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), by Auden and Isherwood 189 The Ascent of F 6 (1936), by Auden and Isherwood 293 On the Frontier (1937-38), by Auden and Isherwood 357 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Coal Face (1935) 421 Night Mail (1935) 422 Negroes (1935) 424 Beside the Seaside (1935) 429 The Way to the Sea (1936) 430 The Londoners (1938?) 433 CABARET AND WIRELESS Alfred (1936) 437 Hadrian's Wall (7937) 441 APPENDICES I Auden and Isherwood's "Preliminary Statement" (1929) 459 1. The "Preliminary Statement" 459 2. Auden's "Suggestions for the Play" 462 VI CONTENTS II The Fronny: Fragments of a Lost Play (1930) 464 III Auden and the Group Theatre, by M J Sldnell 490 IV Auden and Theatre at the Downs School 503 V Two Reported Lectures 510 Poetry and FIlm (1936) 511 The Future of Enghsh Poetic Drama (1938) 513 fEXTUAL NOTES PaId on Both SIdes 525 The EnemIes of a BIshop 530 The Dance of Death 534 1 History, Editions, and Text 534 2 Auden's SynopsIs 542 The Chase 543 The Dog Beneath the Skm 553 1 History, Authorship, Texts, and EditIOns 553 2 Isherwood's Scenano for a New Version of The Chase 557 3 The Pubhshed Text and the Text Prepared for Production 566 4 The First (Pubhshed) Version of the Concludmg Scene 572 5 Isherwood's -

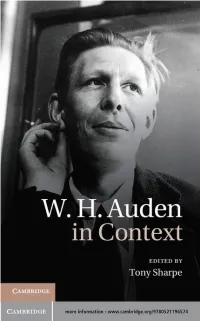

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

First Name Initial Last Name

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Sarah E. Fass. An Analysis of the Holdings of W.H. Auden Monographs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Rare Book Collection. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2006. 56 pages. Advisor: Charles B. McNamara This paper is an analysis of the monographic works by noted twentieth-century poet W.H. Auden held by the Rare Book Collection (RBC) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It includes a biographical sketch as well as information about a substantial gift of Auden materials made to the RBC by Robert P. Rushmore in 1998. The bulk of the paper is a bibliographical list that has been annotated with in-depth condition reports for all Auden monographs held by the RBC. The paper concludes with a detailed desiderata list and recommendations for the future development of the RBC’s Auden collection. Headings: Auden, W. H. (Wystan Hugh), 1907-1973 – Bibliography Special collections – Collection development University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Rare Book Collection. AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOLDINGS OF W.H. AUDEN MONOGRAPHS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL’S RARE BOOK COLLECTION by Sarah E. Fass A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. -

Newsletter 29

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 29 ● December 2007 Contents Tony Sharpe: Paysage Moralisé: Auden and Maps 5 Alan Lloyd: Auden‘s Marriage Retraced 13 John Smart: Two Auden Centennial Festivals 19 Elizabeth Jones: The Spoken Word: Auden‘s BBC Recordings 20 Dana Cook, compiler: Meeting Auden: First Encounters and Initial Impressions (Part IV) 22 Edward Mendelson: A Few Things Auden Never Wrote 27 Sheaves from Sagaland: Three Mysteries Solved 29 Recent and Forthcoming 30 Memberships and Subscriptions 31 An Appeal to Members The Society operates on a proverbial shoestring (almost on a literal one), and membership fees do not quite cover the cost of printing and mailing the Newsletter. Because the costs of a sending a reminder let- ter are prohibitive, we rely on members to send their annual renewals voluntarily. If you have not sent a renewal in the past year, could you kindly do so now? Payment can conveniently be made by any of the methods described on the last page of this number. ISSN 0995-6095 Paysage Moralisé: Auden and Maps Reflecting on the links between his mature poetry and the childhood ‗private secondary sacred world‘ deriving from his fascination with lead-mining and its Pennine landscapes, Auden recalled ‗necessary textbooks on geology and machinery, maps, catalogues, guidebooks, and photographs‘ (CW,1 p. 424), in which his fantasy-life had been grounded before he ever visited the North Pennine moors. When, earlier, he told Geoffrey Grigson that ‗My Great Good Place is the part of the Pennines bounded on the S by Swaledale, on the N by the Romans Wall and on the W by the Eden Valley‘ (17 January 1950; Berg Collection),2 he offered a quasi-cartographical definition of a locality both physically specific and metaphysically general, whose geographical boundaries were defined as if visualised on a map – which is, in fact, the only ‗place‘ on which they could ever be ob- served simultaneously. -

Auden and Religion.', in the Cambridge Companion to W

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 13 November 2008 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Reeves, G. (2004) 'Auden and religion.', in The Cambridge companion to W. H. Auden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 188-199. Cambridge companions to literature. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.2277/0521829623 Publisher's copyright statement: c Cambridge University Press 2004. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk GARETH REEVES Auden and religion Auden liked systems. He liked to categorize and pigeon-hole, but invariably with the awareness that all systems and categories only work on their own terms, that the systematizer is implicated in his creations, that consciousness, while freeing us to explain ourselves to ourselves and to each other, also imprisons us in the explanations we have framed. -

'More Than Glass': Louis Macneice's Poetics of Expansion

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA ‘More than glass’: Louis MacNeice’s Poetics of Expansion A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts & Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Michael A. Moir, Jr. Washington, DC 2012 ‘More than glass’: Louis MacNeice’s Poetics of Expansion Michael A. Moir, Jr., PhD Director: Virgil Nemoianu, PhD The Northern Irish poet and dramatist Louis MacNeice, typically regarded as a minor modernist following in the footsteps of Yeats and Eliot or living in the shadow of Auden, is different from his most important predecessors and contemporaries in the way he attempts to explode conventional ideas of place, presenting human subjects in transit and shifting, melting landscapes, rooms and buildings that tend to blend in with their sur- roundings. While Yeats, Eliot and Auden evince a siege mentality that leads them to build religious or political Utopias easily separable from the chaos of the contemporary world, MacNeice denies the validity of any such imaginary constructs, instead taking apart the boundaries of imaginary private worlds, from rooms to islands to pastoral landscapes. Mac- Neice’s representations of space favor what Fredric Jameson terms ‘postmodern space’: his poems and radio plays operate outside of ideas of ‘home,’ ‘church,’ or ‘nation,’ opposing the rigidity of such places to the fluidity of travel. MacNeice has been much misunderstood and underestimated, and a reappraisal of his career is due, particularly given the amount of material that has been published or reis- sued since his centenary in 2007. -

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: the Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: The Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin Russell, Ph.D. It is widely acknowledged that W. H. Auden became a Christian in about 1940, but relatively little critical attention has been paid to Auden‟s theology, much less to the particular theological sources of Auden‟s faith. Auden read widely in theology, and one of his earliest and most important theological influences on his poetry and prose is Saint Augustine of Hippo. This dissertation explains the Augustinian origin of several crucial but often misunderstood features of Auden‟s work. They are, briefly, the nature of evil as privation of good; the affirmation of all existence, and especially the physical world and the human body, as intrinsically good; the difficult aspiration to the fusion of eros and agape in the concept of Christian charity; and the status of poetry as subject to both aesthetic and moral criteria. Auden had already been attracted to similar ideas in Lawrence, Blake, Freud, and Marx, but those thinkers‟ common insistence on the importance of physical existence took on new significance with Auden‟s acceptance of the Incarnation as an historical reality. For both Auden and Augustine, the Incarnation was proof that the physical world is redeemable. Auden recognized that if neither the physical world nor the human body are intrinsically evil, then the physical desires of the body, such as eros, the self-interested survival instinct, cannot in themselves be intrinsically evil. The conflict between eros and agape, or altruistic love, is not a Manichean struggle of darkness against light, but a struggle for appropriate placement in a hierarchy of values, and Auden derived several ideas about Christian charity from Augustine. -

1934 to 1960

THE BIRDS AtTn THE BEASTS IN AUDEJ:1: A STUDY OF THE USE OF ANHiAI IEAGERY IN TIIE l\fO~J -DRAr:AT Ie POETRY OF "r1. H. AUDEN FRO}: 1934 TO 1960 AN HONORS THESIS SUBHITTED TO THE HONORS CO:r:r:I~TEE lIT PART rAL FUIJFILL!·::ENT OF T3E REQUIRE1-:ENTS FOR ~rHE DEGREE BACHELOR OF SCIENCE E~ E:GUGATION BY OLGA K. DF-'JT INO ADVISER - JOSEPH SATTER1ir~nTE BALL STATE U~IVERSITY I,lUNarE, INDIANA AUGUST, 1965 TEE BIRDS A~m TEiE BEASTS IN AUDE1r The rerutation of W. H. Auden as a poet rests not on the publication of several widely quoted and anthologized poems, but on a consistent and diversified output of technically e~·~cellent and relevant poetry over a nu!::ber of years (1930-1964). Though l;:an;.r of Auden t s individual ~:oems and lines are neDorable, it is rather the recurring patterns of his imagery which catch and hold the attention of his readers and critics. This paper will attempt to deal with one aSl_ect of Auden t S imar:;cry: his 1:!::ages of t::e animal world, and to trace the changes i~ this imagery as it corresponds to Audents ideological evolution froe the position of left-wing, near-Marxist to his positive acceptance of Christianity in the early 1940's. Thouc;h much has been written about various images which perrr,eate the poetry of 'tT. H. Auden--tllB early l)ervasi VB 1mrfare I:;otif, t!:e detective and spy inagery, and the Rilke-like Ithul!lan landscape" technique--crit:.cs have for the most part ignored uhat Randall Jarrell called Auden's "endless procession of birds and beasts"l as the -- lRandall Jarrell, t1Changes of Attitude and Rhetoric in AUden's roetry", Southern Reviel", Autumn, 1941, :po 329. -

1. Taming the Monster 1. Geoffrey Grigson, 'Auden As a Monster', New

Notes 1. Taming the Monster 1. Geoffrey Grigson, ‘Auden as a Monster’, New Verse, 26–7 (1937), 13–17 (p. 13). 2. New Signatures appeared for the first time in 1932, New Country in 1933; New Verse was published from January 1933 until January 1939, New Writing from Spring 1936 until 1950. See Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation: Literature and Politics in England in the 1930s (London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1976), pp. 74–5, 102, 114, 198. 3. Richard Hoggart’s Auden: An Introductory Essay (London: Chatto & Windus, 1951), the first and surprisingly good study of Auden’s works, set the tone with the remark ‘Auden’s poetry is particularly concerned with the pressures of the times’, p. 9. 4. François Duchêne, The Case of the Helmeted Airman: A Study of W. H. Auden’s Poetry (London: Chatto & Windus, 1972) is an unpleasant example of this vivisection attitude that regards the author as a part of the texts and endeavours to supply its reader not only with a textual analysis, but glimpses of the author’s psyche. Herbert Greenberg, Quest for the Necessary: W. H. Auden and the Dilemma of Divided Con- sciousness (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968) is a more sensitive study. 5. Auden himself proves a perceptive commentator on such attitudes when he writes in the preface to The Poet’s Tongue of 1935, ‘The psy- chologist maintains that poetry is a neurotic symptom, an attempt to compensate by phantasy for a failure to meet reality. We must tell him that phantasy is only the beginning of writing; that, on the contrary, like psychology, poetry is a struggle to reconcile the unwilling subject and object; in fact, that since psychological truth depends so largely on context, poetry, the parabolic approach, is the only adequate medium for psychology’ (Pr 108). -

The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden This volume brings together specially commissioned essays by some of the world’s leading experts on the life and work of W. H. Auden, one of the major English-speaking poets of the twentieth century. The volume’s contributors include a prize-winning poet, Auden’s literary executor and editor, and his most recent, widely acclaimed biographer. It offers fresh perspectives on his work from new and established Auden critics, alongside the views of specialists from such diverse fields as drama, ecological and travel studies. It provides scholars, students and general readers with a comprehensive and authoritative account of Auden’s life and works in clear and accessible English. Besides providing authoritative accounts of the key moments and dominant themes of his poetic development, the Companion examines his language, style and formal innovation, his prose and critical writing and his ideas about sexuality, religion, psychoanalysis, politics, landscape, ecology and globalisation. It also contains a comprehensive bibliography of writings about Auden. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO W. H. AUDEN EDITED BY STAN SMITH © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge -

W. H.AUDEN the DYER's

I I By W. H. Auden w. H.AUDEN ~ POEMS ANOTHER TIME THE DOUBLE MAN ON THIS ISLAND THE JOURNEY TO A WAR (with Christopher Isherwood) ASCENT OF F-6 (with Christopher Isherwood) DYER'S ON THE FRONTIER " (with Christopher Isherwood) LETTERS FROM ICELAND (with Louis MacNeice) HAND FOR THE TIME BEING THE SELECTED POETRY OF W. H. AUDEN (Modern Library) and other essays THE AGE OF ANXIETY NONES THE ENCHAFED FLOOD THE MAGIC FLUTE (with Chester Kallman) THE SHIELD OF ACHILLES HOMAGE TO CLIO THE DYER'S HAND Random House · New York ' I / ",/ \ I I" ; , ,/ !! , ./ < I The author wishes to thank the following for permission to reprint 1I1ateriar indilded in these essays: HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD-and JONATHAN CAPE LTD. for selection from "Chard Whitlow" from A Map of Verona and Other Poems by Henry Reed. HARVARD UNIVERSITY PREss-and BASIL BLACKWELL & MOTT LTD. for selection from The Discovery of the Mind by Bruno SnelL HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON, INc.-for selections from Complete r Poems of Rohert Frost. Copyright 1916, 1921, 1923, 1928, 1930, 1939, 1947, 1949, by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc. FIRST PRINTING Copyright, 1948, 1950, 1952, 1953, 1954, © 1956, 1957, 1958, 1960, 1962, ALFRED A. KNOPF, INc.-for selections from The Borzoi Book of by W. H. Auden French Folk Tales, edited by Paul Delarue. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright THE MACMILLAN COMPANy-for selections from Collected Poems of Conventions. Published in New York by Random House, Inc., and simul Marianr.e Moore. Copyright 1935, 1941, 1951 by Marianne Moore; taneously in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada, Limited.