Newsletter 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET of the THIRTIES

V. L. 0. Chittick ANGRY YOUNG POET OF THE THIRTIES THE coMPLETION OF JoHN LEHMANN's autobiography with I Am My Brother (1960), begun with The Whispering Gallery (1955), brings back to mind, among a score of other largely forgotten matters, the fact that there were angry young poets in England long before those of last year-or was it year before last? The most outspoken of the much earlier dissident young verse writers were probably the three who made up the so-called "Oxford group", W. ·H. Auden, Stephen Spender, and C. Day Lewis. (Properly speaking they were never a group in col lege, though they knew one ariother as undergraduates and were interested in one another's work.) Whether taken together or singly, .they differed markedly from the young poets who have recently been given the label "angry". What these latter day "angries" are angry about is difficult to determine, unless indeed it is merely for the sake of being angry. Moreover, they seem to have nothing con structive to suggest in cure of whatever it is that disturbs them. In sharp contrast, those whom they have displaced (briefly) were angry about various conditions and situations that they were ready and eager to name specifically. And, as we shall see in a moment, they were prepared to do something about them. What the angry young poets of Lehmann's generation were angry about was the heritage of the first World War: the economic crisis, industrial collapse, chronic unemployment, and the increasing tP,reat of a second World War. -

CONTENTS Xiii Xxxi Paid on Both Sides

CONTENTS PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi INTRODUCTION xiii THE TEXT OF THIS EDITION xxxi PLAYS Paid on Both Sides [first version] (1928), by Auden 3 Paid on Both Sides [second version] (1928), by Auden 14 The Enemies of a Bishop (1929), by Auden and Isherwood 35 The Dance of Death (1933), by Auden 81 The Chase (1934), by Auden 109 The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), by Auden and Isherwood 189 The Ascent of F 6 (1936), by Auden and Isherwood 293 On the Frontier (1937-38), by Auden and Isherwood 357 DOCUMENTARY FILMS Coal Face (1935) 421 Night Mail (1935) 422 Negroes (1935) 424 Beside the Seaside (1935) 429 The Way to the Sea (1936) 430 The Londoners (1938?) 433 CABARET AND WIRELESS Alfred (1936) 437 Hadrian's Wall (7937) 441 APPENDICES I Auden and Isherwood's "Preliminary Statement" (1929) 459 1. The "Preliminary Statement" 459 2. Auden's "Suggestions for the Play" 462 VI CONTENTS II The Fronny: Fragments of a Lost Play (1930) 464 III Auden and the Group Theatre, by M J Sldnell 490 IV Auden and Theatre at the Downs School 503 V Two Reported Lectures 510 Poetry and FIlm (1936) 511 The Future of Enghsh Poetic Drama (1938) 513 fEXTUAL NOTES PaId on Both SIdes 525 The EnemIes of a BIshop 530 The Dance of Death 534 1 History, Editions, and Text 534 2 Auden's SynopsIs 542 The Chase 543 The Dog Beneath the Skm 553 1 History, Authorship, Texts, and EditIOns 553 2 Isherwood's Scenano for a New Version of The Chase 557 3 The Pubhshed Text and the Text Prepared for Production 566 4 The First (Pubhshed) Version of the Concludmg Scene 572 5 Isherwood's -

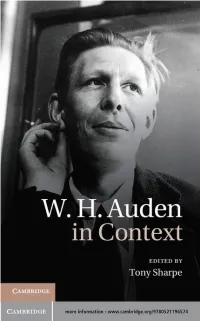

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: the Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin

ABSTRACT Augustinian Auden: The Influence of Augustine of Hippo on W. H. Auden Stephen J. Schuler, Ph.D. Mentor: Richard Rankin Russell, Ph.D. It is widely acknowledged that W. H. Auden became a Christian in about 1940, but relatively little critical attention has been paid to Auden‟s theology, much less to the particular theological sources of Auden‟s faith. Auden read widely in theology, and one of his earliest and most important theological influences on his poetry and prose is Saint Augustine of Hippo. This dissertation explains the Augustinian origin of several crucial but often misunderstood features of Auden‟s work. They are, briefly, the nature of evil as privation of good; the affirmation of all existence, and especially the physical world and the human body, as intrinsically good; the difficult aspiration to the fusion of eros and agape in the concept of Christian charity; and the status of poetry as subject to both aesthetic and moral criteria. Auden had already been attracted to similar ideas in Lawrence, Blake, Freud, and Marx, but those thinkers‟ common insistence on the importance of physical existence took on new significance with Auden‟s acceptance of the Incarnation as an historical reality. For both Auden and Augustine, the Incarnation was proof that the physical world is redeemable. Auden recognized that if neither the physical world nor the human body are intrinsically evil, then the physical desires of the body, such as eros, the self-interested survival instinct, cannot in themselves be intrinsically evil. The conflict between eros and agape, or altruistic love, is not a Manichean struggle of darkness against light, but a struggle for appropriate placement in a hierarchy of values, and Auden derived several ideas about Christian charity from Augustine. -

Auden at Work / Edited by Bonnie Costello, Rachel Galvin

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–45292–4 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Bonnie Costello and Rachel Galvin 2015 Individual chapters © Contributors 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–45292–4 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Auden's Revisions

Auden’s Revisions By W. D. Quesenbery for Marilyn and in memoriam William York Tindall Grellet Collins Simpson © 2008, William D. Quesenbery Acknowledgments Were I to list everyone (and their affiliations) to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their help in preparing this study, the list would be so long that no one would bother reading it. Literally, scores of reference librarians in the eastern United States and several dozen more in the United Kingdom stopped what they were doing, searched out a crumbling periodical from the stacks, made a Xerox copy and sent it along to me. I cannot thank them enough. Instead of that interminable list, I restrict myself to a handful of friends and colleagues who were instrumental in the publication of this book. First and foremost, Edward Mendelson, without whose encouragement this work would be moldering in Columbia University’s stacks; Gerald M. Pinciss, friend, colleague and cheer-leader of fifty-odd years standing, who gave up some of his own research time in England to seek out obscure citations; Robert Mohr, then a physics student at Swarthmore College, tracked down citations from 1966 forward when no English literature student stepped forward; Ken Prager and Whitney Quesenbery, computer experts who helped me with technical problems and many times saved this file from disappearing into cyberspace;. Emily Prager, who compiled the Index of First Lines and Titles. Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Table of Contents 4 General Introduction 7 Using the Appendices 14 PART I. PAID ON BOTH SIDES (1928) 17 Appendix 19 PART II. -

The Early Work of David Jones and Wh Auden A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO IRENIC MODERNISM: THE EARLY WORK OF DAVID JONES AND W. H. AUDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JOHN U. NEF COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL THOUGHT BY JOSEPH EDWARD SIMMONS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2019 !" S#$%& TABLE OF CONTENTS L#'( ! I&&)'("*(#!+'.........................................................................................................................#, L#'( ! T*$&-'..................................................................................................................................., A./+!0&-123-+('..........................................................................................................................,# A$'("*.(........................................................................................................................................,### C4*5(-" 1: I+("!1).(#!+...................................................................................................................1 C4*5(-" 2: A2*#+'( (4- P!-( *' D#,#+- T"*+'5*"-+( E%-$*&&........................................................62 C4*5(-" 7: R#()*&' ! R-.!2+#(#!+................................................................................................98 C4*5(-" 9: T4- P"!$&-3 ! P!-(#. F"*("#.#1-.............................................................................192 C4*5(-" 6: T4- P-*.- ! P!-(#. I+(-"5"-(*(#!+...........................................................................197 C4*5(-" -

Newsletter 29

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 29 ● December 2007 Memberships and Subscriptions Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Individual members £9 $15 Students £5 $8 Institutions £18 $30 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should send sterling cheques or checks in US dollars payable to ‘The W. H. Auden Society’ to Katherine Bucknell, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW. Receipts available on request. Payment may also be made by credit card through the Society’s web site at: http://audensociety.org/membership.html The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. The Newsletter is edited by Farnoosh Fathi. Submissions may be made by post to: The W. H. Auden Society, 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW; or by e-mail to: thenewsletter-at-audensociety.org All writings by W. H. Auden in this issue are copyright 2007 by The Estate of W. H. Auden. Please see the Appeal to Members that appears on the Contents page of this number. 31 Recent and Forthcoming W. H. Auden, by Tony Sharpe, a title in the Routledge Guides to Lite- Contents rature Series, was published in the autumn of 2007.. Tony Sharpe: W. H. Auden: Prose, Volume III, 1949-1955 (The Complete Works of Paysage Moralisé: Auden and Maps 5 W. H. Auden), edited by Edward Mendelson, will be published by Alan Lloyd: Princeton University Press in December 2007. Auden’s Marriage Retraced 13 The Ilkley Literature Festival held several Auden-related events in John Smart: September and October 2007. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 75-15,270 OLDHAM, Perry Donald, Jr., 1943- the CONVERSATIONAL POETRY of W

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if e ^ n tia l to the understanding of the dissertation. -

W. H. Auden and Opera: Studies of the Libretto As Literary Form

W. H. AUDEN AND OPERA: STUDIES OF THE LIBRETTO AS LITERARY FORM Matthew Paul Carlson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: George S. Lensing Erin G. Carlston Tim Carter Allan R. Life Eliza Richards !2012 Matthew Paul Carlson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MATTHEW PAUL CARLSON: W. H. Auden and Opera: Studies of the Libretto as Literary Form (Under the direction of George S. Lensing) From 1939 to 1973, the poet W. H. Auden devoted significant energy to writing for the musical stage, partnering with co-librettist Chester Kallman and collaborating with some of the most successful opera composers of the twentieth century, including Benjamin Britten, Igor Stravinsky, and Hans Werner Henze. This dissertation examines Auden’s librettos in the context of his larger career, relating them to his other poetry and to the aesthetic, philosophical, and theological positions set forth in his prose. I argue that opera offered Auden a formal alternative to his own early attempts at spoken verse drama as well as those of his contemporaries. Furthermore, I contend that he was drawn to the role of librettist as a means of counteracting romantic notions of the inspired solitary genius and the sanctity of the written word. Through a series of chronologically ordered analyses, the dissertation shows how Auden’s developing views on the unique capacities of opera as a medium are manifested in the librettos’ plots. -

The Cambridge Companion to W. H

Cambridge University Press 0521829623 - The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden Edited by Stan Smith Index More information INDEX Auden’s works are subdivided below into Poetry (volumes and individual poems), Plays (includ- ing libretti, radio and film scripts) and Prose (volumes, essays, chapters). The latter includes prose passages from ‘mixed’ volumes of verse and prose, where such extracts have individual titles and are discussed separately in the text, and anthologies edited by Auden, whether of prose or verse. Poetry and prose collections and critical and biographical sources are indexed only when they are discussed in their own right, but not when identifying references. Where there are alternative titles both are indicated. The poet himself is not indexed. Abyssinia 28, 157 Ashbery, John 4, 22, 227, 230 Ackerley, J. R. 178 Some Trees 230 My Father and Myself 178 Asperger’s Syndome 16 Adams, Anna Atwell, Mabel Lucie 135 A Reply to Intercepted Mail 236 Auden, Bernard xiv Adams, Henry 45 Auden, Constance Rosalie (nee)´ Bicknell xiv, Aeschylus 85 16, 154 Agape 18, 31, 32, 33, 37, 113, 157, Auden, George Augustus xiv–xv, 4, 16 175 Auden, John xiv, 17 Aguledo, Juan Sebastian and Murguıa,´ Auden Society Newsletter 234, 246 Guillermo Aguledo 214 Auden, W. H.: poetry The Sentient Universe 214 About the House (book) xix, 23, 64, 66, ‘Auden’s Question, Gould’s 222 Answer’ 214 Academic Graffiti xxi, 104 Allison, Drummond 230 ‘Address to the Beasts’ 223–4 Amis, Kingsley ‘Adolescence’ 203 ‘Socialism and the Intellectuals’ 231–2 ‘After Reading a Child’s Guide to Modern Amundsen, Roald 88 Physics’ 214 Anderson, Hedli 131 The Age of Anxiety , xix, 5, 7, 10, 21, Andreirsson, Kristian 74–5 46–7, 49–50, 88, 94, 112, 128, 133, 134, Anglo-German Naval Agreement 28 146, 206, 207, 235 Anselm, St 189 ‘The Aliens’ 66 Ansen, Alan 50 ‘Amor Loci’ 65, 211 The Table Talk of W. -

And Twenty-First-Century Poetry Abstract This Article Begins by Noting T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository New Old English: The Place of Old English in Twentieth- and Twenty-first-Century Poetry Abstract This article begins by noting that the narrative coherence of literary history as a genre, and the inclusions and exclusions that it is forced to make, depend on the often unacknowledged metaphors that attend its practice. Literary history which is conceived as an unbroken continuity (‘the living stream of English’) has found the incorporation of Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon) to be problematic and an issue of contention. After surveying the kind of arguments that are made about the place of Old English as being within or without English literary tradition, this article notes that a vast body of twentieth and twenty-first century poetry, oblivious to those turf-wars, has concerned itself with Old English as a compositional resource. It is proposed that this poetry, a disparate and varied body of work, could be recognized as part of a cultural phenomenon: ‘The New Old English’. Academic research in this area is surveyed, from the 1970s to the present, noting that the rate of production and level of interest in New Old English has been rapidly escalating in the last decade. A range of poets and poems that display knowledge and use of Old English largely overlooked by criticism to date is then catalogued, with minimal critical discussion, in order to facilitate further investigation by other scholars. This essay argues that the widespread and large-scale reincorporation of an early phase of English poetic tradition, not in contiguous contact with contemporary writing for so many centuries, is such an unprecedented episode in the history of any vernacular that it challenges many of the metaphors through which we attempt to pattern texts into literary historical narrative.