Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

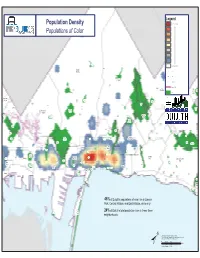

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

Evaluation of Humic Substances Used in Commercial Fertilizer Formulations

Final report FREP Project 07-0174 Evaluation of humic substances used in commercial fertilizer formulations T.K. Hartz Extension Specialist Department of Plant Sciences University of California 1 Shields Ave Davis, CA 95616 (530) 752-1738 [email protected] Executive summary: This project examined the effects of five commercial humic acid formulations on soil microbial activity, seed germination, early growth, nutrient uptake and crop productivity of lettuce and processing tomato. Humic acid solutions ranging from 250-750 PPM a.i. were used to imbibe coated lettuce seed; those seeds germinated at the same rate and frequency as seed imbibed with deionized water. In a greenhouse trial lettuce plants were grown from seed in pots of four field soils differing in phosphorus availability. The pots received pre-seeding banded application of humic acid alone, P fertilization (liquid 10-34- 0) alone, both humic acid and P fertilization, or neither treatment. In one of the four soils humic acid plus P increased lettuce growth above that of P fertilization alone. In the absence of P fertilization, no humic acid formulation increased lettuce growth in any soil. P fertilization increased plant P uptake in all soils, but humic acid did not increase P uptake in any soil. The effect of humic acid on soil microbial activity was evaluated in a laboratory assay using a low organic matter soil and a high organic matter soil (0.8 and 2.5% organic matter, respectively). The soils were wetted with tap water alone, P fertilizer solution, humic acid solution, or a solution containing both humic acid and P fertilizer. -

Hydrologic Soil Groups

AppendixExhibitAppendix A: Hydrologic AB Soil Synthetic Groups Hydrologic for theRainfall United SoilStates Distributions Groups and Rainfall Data Sources Soils are classified into hydrologic soil groups (HSG’s) Disturbed soil profiles to indicate the minimum rate of infiltration obtained for bareThe highest soil after peak prolonged discharges wetting. from Thesmall HSG watersheds’s, which arein the UnitedAs a result States of areurbanization, usually caused the soil by profileintense, may brief be rain- con- A,falls B, that C, and may D, occur are one as distinctelement eventsused in or determining as part of a longersiderably storm. These altered intense and the rainstorms listed group do not classification usually ex- may runofftended curve over anumbers large area (see and chapter intensities 2). For vary the greatly. conve- One commonno longer practice apply. inIn rainfall-runoffthese circumstances, analysis use is tothe develop follow- niencea synthetic of TR-55 rainfall users, distribution exhibit A-1 to uselists in the lieu HSG of actualclassifi- storming events. to determine This distribution HSG according includes to themaximum texture rainfall of the cationintensities of United for the States selected soils. design frequency arranged in a sequencenew surface that soil, is critical provided for thatproducing significant peak compaction runoff. has not occurred (Brakensiek and Rawls 1983). TheSynthetic infiltration raterainfall is the rate distributions at which water enters the soil at the soil surface. It is controlled by surface condi- HSG Soil textures tions.The length HSG ofalso the indicates most intense the transmission rainfall period rate contributing—the rate to the peak runoff rate is related to the time of concen- A Sand, loamy sand, or sandy loam attration which (T thec) for water the watershed.moves within In thea hydrograph soil. -

COONAWARRA \ Little Black Book Cover Image: Ben Macmahon @Macmahonimages COONAWARRA \

COONAWARRA \ Little Black Book Cover image: Ben Macmahon @macmahonimages COONAWARRA \ A small strip of land in the heart of the Limestone Coast in South Australia. Together our landscape, our people and our passion, work in harmony to create a signature wine region that delivers on a myriad of levels - producing wines that unmistakably speak of their place and reflect the character of their makers. It’s a place that gets under your skin, leaving an indelible mark, for those who choose it as home and for those who keep coming back. We invite you to Take the Time... Visit. Savour. Indulge. You’ll smell it, taste it and experience it for yourself. COONAWARRA \ Our Story Think Coonawarra, and thoughts of There are the ruddy cheeks of those who tend the vines; sumptuous reds spring to mind – from the the crimson sunsets that sweep across a vast horizon; and of course, there’s the fiery passion in the veins of our rich rust-coloured Terra Rossa soil for which vignerons and winemakers. Almost a million years ago, it’s internationally recognised, to the prized an ocean teeming with sea-life lapped at the feet of the red wines that have made it famous. ancient Kanawinka Escarpment. Then came an ice age, and the great melt that followed led to the creation of the chalky white bedrock which is the foundation of this unique region. But nature had not finished, for with her winds, rain and sand she blanketed the plain with a soil rich in iron, silica and nutrients, to become one of the most renowned terroir soils in the world. -

Soil Fertility Research in Sugarcane in 2007

SOIL FERTILITY RESEARCH IN SUGARCANE IN 2007 Brenda S. Tubaña, Chuck Kennedy, Allen Arceneaux and Jasper Teboh School of Plant, Environmental and Soil Sciences In Cooperation with Sugar Research Station Summary Two experiments were conducted in 2007 to test the effect of different N rates on the yield and yield components of current sugarcane varieties. Spring application of N at rates of 0, 40, 80 and 120 lbs N ac -1 to LCP85-384, HoCP96-540 and L99-226 had no effect on plantcane yield. However, 40 and 80 lbs N ac -1 resulted in significantly higher sugar yield when compared with 120 lbs N ac -1 application rate. Stubble cane yield of LCP85-384, Ho95-988, and L97-128 showed response to spring N fertilization. Linear-plateau models estimated N rates that ranged from 42 to 80 lbs N ac -1 for optimum cane and sugar yield of these varieties. Two trials were also conducted to determine the effect of fertilizer adjuvant. Applications of Trimat, PGR and foliar NPK in addition with normal fertilization did not result in significant increases in the first- stubble cane and sugar yield of Ho95-988 and L97-128. Similarly, application of Helena Chemical products on top on standard practices did not result in significant increases in second- stubble cane and sugar yield of L97-128. Objectives This research was designed to provide information on soil fertility in an effort to help cane growers produce maximum economic yields and increase profitability in sugarcane production. This annual progress report is presented to provide the latest available data on certain practices and not as a final recommendation for growers to use all of these practices. -

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions Summer 2018 2018 Adventure Zone Family Fun Center 218-740-4000 / www.adventurezoneduluth.com SUMMER HOURS: Memorial Day - Labor Day Sunday - Thursday: 11am – 10pm Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight WINTER HOURS: Monday – Thursday: 3 – 9pm Friday & Saturday: 11am – Midnight Sunday: 11am – 9pm DESCRIPTION: “Canal Park’s fun and games from A to Z”. There is something for everyone! The Northland’s newest family attraction boasts over 50,000 square feet of fun, featuring multi-level laser tag, batting cages, mini golf, the largest video/redemption arcade in the area, Vertical Endeavors rock climbing walls, virtual sports challenge, a kid’s playground and more! Make us your party headquarters! RATES: Laser Zone: Laser Tag $6 North Shore Nine: Mini Golf $4 Sport Plays: Batting Cages or Virtual Sports Simulator $1.75 per play or 3 plays for $5 DIRECTIONS: Located in Duluth’s Canal Park Business District at 329 Lake Avenue South, just blocks from Downtown Duluth and the famous Aerial Lift Bridge. DEALS: Adventure Zone offers many Daily Deals and Weekly Specials. A sample of those would include the Ultra Adventure Pass for $17, a Jr. Adventure Pass for $11, Monday Fun Day, Ten Buck Tuesday, Thursday Family Night and a Late Night Special on Fri & Sat for $10! AMENITIES: Meeting and Banquet spaces available with catering options from local restaurants. 2018 Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” 218-740-3535 / www.bentleyvilleusa.org WINTER HOURS: November 17 – December 26, 2018 Sunday – Thursday: 5 - 9pm Friday & Saturday: 5 – 10pm DESCRIPTION: A non-profit, charitable organization that holds a free annual family holiday light show – complete with Santa, holiday music and fire pits for roasting marshmallows. -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Recommended Draft Network Route Frequency and Span Summary DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route Replacement Overview Table Previous Route Recommended Draft Network Replacement Route 1 101 Route 2 101, 103 Route 2F Service to Fon du Lac discontinued Route 2X* 103 Route 3 101, 109 Route 3X* 109 Route 4+ 109 Route 5 101, 103, 107, 108 Route 6 101 Route 7 101, 103 Route 7A 101 Route 7X* 103 Route 8 107, 108 Route 9M 108 Route 9MT 107, 108 Route 10 102, 104, 108, 113 Route 10E+ 102, 104, 113, Route 10H 102 Route 11 102, 105 Route 11K 102, 105, 106, 112 Route 11M+ 105, 112 Route 12 106 Route 13 104, 112 Route 14W Service to Observation Hill discontinued Route 15 113 Route 16 110, 111 Route 16X* 110, 111 Route 17+ 110 Route 17B Service to Billings Park discontinued Route 17S 110 Route 18 112 Route 19 114 Route 23 104, 105 Route S1 101, 109 *Peak Period Express services were reallocated into frequency on local services +Sections of this route discontinued. Check specific route changes for more details Routes 101 & 102 denote high frequency (pre-BRT) service DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route 101: Spirit Valley-DTC-UMD Route 101 is one of two, pre-BRT routes that make up the high frequency spine of the Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network. -

Soil Survey of Sequoia National Forest, California (1996) Part II of II

622 Dome-Chaix outcrop association, 30 to 50 percent slopes. Illlil This map unit is on mountainsides and ridges. Slope is 30 to 50 percent. The native plant communities are Yellow Pine Forest and Mixed Conifer Forest. Elevation is 5,000 to 8,040 feet. The average annual precipitation is about 24 to 51 inches. This unit is 35 percent Dome sandy loam, 30 percent Chaix sandy loam, and 20 percent Rock outcrop. Dome Chaix Rock outcrop 40 to 60 in 20 to 40 in Moderate to low Low t 5 to 6 in 3 to 4 in | 2 in 2 in I Moderately rapid Moderately rapid B B Well drained Well drained or somewhat excessively drained Rapid Rapid Moderate Moderate 0.20 0.24 ^ SM SM Intermediate Intermediate 2ep 3eP 85 to 164 50 to 84 Suitable Suitable Regeneration difficulty—d and f Summer Summer Plant competition, steep slopes II II Included in this unit are small areas of Chawanakee soils and Junipero family soils. Included areas make up about 15 percent of the total acreage. The Dome soil is deep and formed in residuum derived from granitic rock. Typically, the surface layer is grayish brown sandy loam about 7 inches thick. The subsoil is pale brown sandy loam about 21 inches thick. The subsoil is very pale brown sandy loam about 22 inches thick over highly weathered granitic rock. In some areas the surface layer is coarse sandy loam. The Chaix soil is moderately deep and formed in residuum derived from granitic rock. Typically, the surface layer is brown sandy loam about 7 inches thick. -

Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Final MPDF

St. Michael Big Marine ! ! Anoka Lake ! Berning Mill !Rogers Champlin ! Anoka HennepinMis siss Fletcher ip Maple Island ! pi ! R Lino Lakes ! i Centerville v ! er ! on Hanover ! Hugo ti Wright ! Coon Creek Maple Grove ! Hennepin arnelian Junc rcola Anoka Withrow C ! A Burschville ! ! ! !Osseo Ramsey te Bear Beach Whi ! Bald Eagle ! !Dupont !Corcoran !Brooklyn Park on ! ! Dellwood Rockford ! Fridley White di ! White me ! C Bear luth Juncti Lake Sarah ardigan Bear ahto ! Du ! Lake !M Lake !Leighton New Junction Vadnais Heights ! Stillwater ! Columbia Brighton ! ! Lor ! ! ood Heights etto rchw ! ! Bi Hamel ! ! ! Little Canada Medi Robbinsdale North c Bayport ine La ! ! Ditter ! St. Paul S Lon ! t Roseville . ! C gL r Maple Plain k Golden Gloster o e ! a i k ! Valley ! x e ! ! Lake Elmo R i Lyndale ! ! v ! Oakdale e ! r ! Midvale Ramsey ! Wayzata Washington Minneapolis Spring P Minnet ! onka Saint Paul St. D ! ! M . Oakbury Lakeland ! ark Lake ills ! Mound ! ! Louis D ! Minnetonka ! D . ! Park ! . ! . ! ! D . Deephaven ! ! ! West Highwood . ! Hopkins ! D St. Paul ! Glen Lake . ! ! ! Afton D ! St. Bonifacius M ! Excelsior . .! is Oak Terrace! South s ! i s s D ! St. Paul .! ! Fort . i ! Mendota . p Carver p Snelling . ! i D . ! Waconia R iver Newport ! D Chanhassen .! D ! ! Atwood D !Victoria Inver Grove ! ! D Eden Prairie .! St. Paul Cottage Grove ! !D Park .! Oxboro ! Bl oo D Hennep Bloomington .! mington Ferry ! ! Nicols Wescott ! D . ! in ! er . ! iv ! Augusta ta R ! Langdon ! so D nne . ! i ! ! M D Map adapted from the MN DNR divison of Fish and Wildlife 100k Lakes and Rivers and 100k Hydrography, Railroad Commissioners Map of Minnesota, 1930, and MN DOT Abandonded Railroads GIS data. -

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition Submitted to the Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Constance Arzigian Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse July 2008 MINNESOTA STATEWIDE MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM FOR THE WOODLAND TRADITION FINAL Mn/DOT Agreement No. 89964 MVAC Report No. 735 Authorized and Sponsored by: Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 1725 State Street La Crosse WI 54601 Principal Investigator and Report Author Constance Arzigian July 2008 NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. __X_ New Submission ____ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Woodland Tradition in Minnesota B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Brainerd Complex: Early Woodland in Central and Northern Minnesota, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 400 The Southeast Minnesota Early Woodland Complex, 500–200 B.C. The Havana-Related Complex: Middle Woodland in Central and Eastern Minnesota, 200 B.C.–A.D. -

Xii. Pastoral Records

XII. PASTORAL RECORDS Record of Ministerial Service The basic format used for printing the record is: • Ed: (Degree) (School) (Year granted), (Repeat as necessary); Adm: PM (or OT or P as appropriate) (Year); FM (Year); Ord: D, if applicable (Year); App: (Conference - unnecessary if all service is in the Minnesota Conference) (Church or Special Appt.) (First year appt.), (Repeat as necessary). Necessary variations are made to fit differing circumstances. For example, churches served when the pastor’s appointment was “to attend school,” are listed in parentheses following “AS” and the year. Pastoral records contain official appointments by the bishop and do not include ministries or churches served on a supply basis. Post retirement appointments are not listed. • Abbreviations include: OT (on trial); P (provisional); PM (provisional member); FM (full member); D (deacon); FD (full deacon); E (elder); Ed (education); Adm (admitted); Comm (commissioned); Ord (ordained); AS (attending school); DS (district superintendent); Ct (circuit); Sup (supernumerary); SL (sabbatical leave); LOA (leave of absence); DL (disability leave); IncL (incapacity leave); FamL (family leave); PersL (personal leave); R (retired); RE (retired full elder); RS (retired supply); RM (retired minister); RL (retired local pastor); NA (not appointed); PE (provisional elder); HL (honorable location). Please report errors and omissions to the conference secretary. A. Elders in Full Connection AASTUEN, HOLLY WILLIAMS—Ed: BA St Olaf 1982; MDiv Iliff 1988; Adm: PM 1986; FM 1990; -

Download Here

City of Duluth PARKS AND GREEN SPACE Amity Park 2940 Seven Bridges Rd Arlington Athletic Complex 601 S Arlington Ave Bardon's Peak Forest 105th Ave W & Skyline Dr Bardon's Peak Blvd Hwy 1 at Knowlton Creek to Becks Rd Bayfront Festival Park 700 Railroad St Birchwood Park 222 W Heard St Blackmer Park 8301 Beverly St Boy Scout Landing 1 Commonwealth Ave Brewer/Bellevue Park 2588 Haines Rd Brighton Beach Park (Kitchi Gammi) 6202 Congdon Blvd Bristol Beach Park Congdon Blvd & Leighton St Buffalo Park St. Marie St & Vermilion Rd Canal Park Canal Park Drive & Morse St Carson Park 1101 131st Ave. W Cascade Park 600 N Cascade St Central Hillside Park 3 E 3rd St Central Park 1515 W 3rd St Chambers Grove Park 100 134th Ave W Chester Park (upper) 1800 E Skyline Parkway Chester Park (lower) 501 N 15th Ave Civic Center 5th Ave W & 1st St Cobb Park 20 Redwing St Como Park (Glen Avon) 2401 Woodland Ave Congdon Boulevard 60th Ave E to Lake Co Line along Shore Congdon Park 3204 Congdon Park Dr Downer Park 3615 Vermillion Rd Duluth Heights Park 33 W Mulberry St Endion Park 1616 E 2nd St Enger Golf Course 1801 W Skyline Blvd Enger Park 1601 Enger Tower Rd Ericson Place 5716 W Skyline Pkwy Fairmont Park 72nd Ave W & Grand 5th Ave Mall Michigan St to 1st St 59th Ave W Park Center Island at 59th Ave W Fond du Lac Park 410 131st Ave W 42nd Ave E Park 42nd Ave E below London Rd Franklin Square (12th St Beach) 1220 S Lake Ave Franklin Tot Lot 1202 Minnesota Ave Gary New Duluth Park 801 101st Ave W Gary New Duluth Dog Park 822 101st Ave W Gasser Park 96th Ave