Descargar Este Artículo En Formato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ceramics of Lubaantun: Stasis and Change in the Southern Belize Region during the Late and Terminal Classic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6zf41162 Author Irish, Mark David Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Ceramics of Lubaantun: Stasis and Change in the Southern Belize Region during the Late and Terminal Classic A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Mark David Irish Committee in charge: Professor Geoffrey E. Braswell, Chair Professor Paul S. Goldstein Professor Thomas E. Levy 2015 Copyright Mark David Irish, 2015 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Mark David Irish is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii DEDICATION In recognition of all of the support they have given me throughout my years of education; for proof-reading countless essays and the source of endless amounts of constructive criticism; for raising me to value learning and the pursuit of knowledge; for always being there when I needed someone to talk to; this thesis is dedicated to my family, including my mother Deanna, my father John, my sister Stephanie, and my wonderful wife Karla. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………..…. iii Dedication…………………………………………………………………………….. iv Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………… v List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………. vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………….... vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………. viii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Background…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 The Southern Belize Region…………………………………………………… 12 History of Lubaantun…………………………………………………………. -

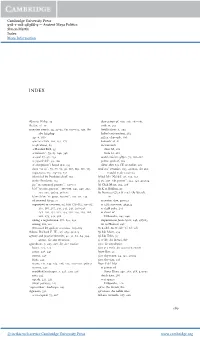

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize

Reports Submitted to FAMSI: Phillip J. Wanyerka The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Posted on December 1, 2003 1 The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Table of Contents Introduction The Glyphic Corpus of Lubaantún, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions The Ceramic Inscriptions The Glyphic Corpus of Nim LI Punit, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Xnaheb, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Pusilhá, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions The Sculptural Monuments Miscellaneous Texts and Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Uxbenka, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Texts Miscellaneous Sculpture Other Miscellaneous Monuments Tzimín Ché Stela 1 Caterino’s Ruin, Monument 1 Choco, Monument 1 Pearce Ruin, Phallic Monument The Pecked Monuments of Southern Belize The Lagarto Ruins Papayal The Cave Paintings Acknowledgments List of Figures References Cited Phillip J. Wanyerka Department of Anthropology Cleveland State University 2121 Euclid Avenue (CB 142) Cleveland, Ohio 44115-2214 p.wanyerka @csuohio.edu 2 The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Introduction The following report is the result of thirteen years of extensive and thorough epigraphic investigations of the hieroglyphic inscriptions of the Maya Mountains region of southern Belize. The carved monuments of the Toledo and Stann Creek Districts of southern Belize are perhaps one of the least understood corpuses in the entire Maya Lowlands and are best known today because of their unusual style of hieroglyphic syntax and iconographic themes. Recent archaeological and epigraphic evidence now suggests that this region may have played a critical role in the overall development, expansion, and decline of Classic Maya civilization (see Dunham et al. -

University of Copenhagen

Kings of the East Altun Ha and the Water Scroll Emblem Glyph Helmke, Christophe; Guenter, Stanley; Wanyerka, Phillip Published in: Ancient Mesoamerica DOI: 10.1017/S0956536117000256 Publication date: 2018 Document license: Other Citation for published version (APA): Helmke, C., Guenter, S., & Wanyerka, P. (2018). Kings of the East: Altun Ha and the Water Scroll Emblem Glyph. Ancient Mesoamerica, 29(1), 113-135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536117000256 Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Ancient Mesoamerica, 29 (2018), 113–135 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2018 doi:10.1017/S0956536117000256 KINGS OF THE EAST: ALTUN HA AND THE WATER SCROLL EMBLEM GLYPH Christophe Helmke,a Stanley P. Guenter,b and Phillip J. Wanyerkac aInstitute of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, Karen Blixens Plads 8, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark bFoundation for Archaeological Research and Environmental Studies, 164 W 400 N, Rupert, Idaho 83350 cDepartment of Criminology, Anthropology, and Sociology, Cleveland State University, 2121 Euclid Ave. RT 932, Cleveland, Ohio 44115 ABSTRACT The importance of emblem glyphs to Maya studies has long been recognized. Among these are emblems that have yet to be conclusively matched to archaeological sites. The Water Scroll emblem glyph is one such example, although it appears numerous times in the Classic Maya written corpus between the sixth and the eighth centuries. These many references are found at a variety of sites across the lowlands, attesting to the importance of this ancient kingdom and the kings who carried this title. In the present paper, we review the epigraphic and archaeological evidence and propose that this may be the royal title of the kings who reigned from Altun Ha, in the east central Maya lowlands, in what is now Belize. -

Central-America-7-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 757 Index El Salvador 274 Ceibal (G) 206-7 ABBREVIATIONS Guatemala 85 Cerros (B) 240 ACTB AustralianBelize Capital Honduras 339 Chenes Sites (M) 53 Territory CR Costa Rica Nicaragua 451 Chichén Itzá (M) 56-7 NSW New South Wales ES El Salvador Panama 633-4 Chinkultic ruins (M) 49 NT Northern Territory G Guatemala anthropology museums, see also Cihuatán (ES) 290 Qld Queensland H Honduras archaeology museums, art Cobá (M) 70 SA South Australia M Mexico museums, cultural museums, Copán (H) 374-9, 376, 7 Tas Tasmania INDEX N Nicaragua galleries, museums Dzibilchaltún (M) 56 Vic Victoria P Panama Museo de Antropología (N) 495 Edzná (M) 53 WA Western Australia Museo de Antropología e Historia Ek’ Balam (M) 57 de San Pedro Sula (H) 364 El Cedral (M) 67 A Museo Nacional de Antropología El Mirador (G) 207 accommodations 710-11, see also David J Guzmán (ES) 282 El Perú (G) 207 individual countries, major cities Museo Nacional de Historia y El Pilar (B) 246 useful phrases 742 Antropología Villa Roy (H) 346 El Zotz (G) 207 activities 711-13, see also individual Museo Regional de Antropología Finca El Baúl (G) 159-60 activities, countries (M) 55 Ixcún (G) 198 agrotourism 156 Antigua (G) 102-15, 104-5 Iximché (G) 123 Agua Azul (M) 49 accommodations 111-12 Izamal (M) 57 Ahuachapán (ES) 301-2 activities 108-9 Joya de Cerén (ES) 290 air travel attractions 107-8 K’umarcaaj (G) 135 airlines 726 courses 109-10 Lamanai (B) 238 Belize 223-4 drinking 113-14 Las Sepulturas (H) 379 Costa Rica 532-3 emergencies 103 Lubaantun -

Copyrighted Material

Mountain Pine Ridge area, Mayflower Bocawina National Index 248 Park, 166 Orange Walk Town, 204 Nim Li Punit, 191 See also Accommodations and Placencia, 172, 174 near Orange Walk Town, Restaurant indexes, below. Punta Gorda, 187–188 206–207 San Ignacio, 232 near Punta Gorda, 190–191 Ak'Bol Yoga Retreat (Ambergris San Ignacio area, 234 Caye), 120 suggested itinerary, 62–63 General Index Aktun Kan (Cave of the Serpent; Tikal, 264–269 A near Santa Elena), 278 Topoxté (Guatemala), 279 Almond Beach Belize, 11 Uaxactún (Guatemala), AAdictos (Flores), 283 GENERAL INDEX Altun Ha, 9, 200–201 279–280 Abolition Act of 1833, 24 Ambar (Ambergris Caye), 122 Xunantunich, 235 Accommodations, 53. See also Ambergris Caye, 11, 56, 107, Yaxhá (Guatemala), 278–279 Accommodations Index 110–133 Architecture, 26 Ambergris Caye, 122–128 accommodations, 122–128 Area codes, 284 Belize City, 91–94 fire department, 115 Armadillo, 298 Belmopan, 228–229 getting around, 114 Art, 26 lodges near, 230–231 nightlife, 132–133 Art Box (Belmopan), 228 best, 12–15 orientation, 114–115 Art galleries Caye Caulker, 141–143 police, 115 Belize City, 98, 104 Corozal Town, 217–219 post office, 115 Caye Caulker, 140–141 Dangriga, 159–160 restaurants, 128–132 Dangriga, 158 discounts for children, 47 shopping, 121 Placencia, 179 Hopkins Village, 169–171 sights and attractions, 115–121 Art 'N Soul (Placencia), 179 Orange Walk Town, 207–208 taxis, 114 Arts & Crafts of Central America the outer cayes, 163–165 traveling to and from, 110, 112 (San Ignacio), 239 Placencia, 179–183 Ambergris -

6 Dispersión Y Estructura De Las Ciudades Del Sureste De Petén, Guatemala

6 DISPERSIÓN Y ESTRUCTURA DE LAS CIUDADES DEL SURESTE DE PETÉN, GUATEMALA Juan Pedro LAPORTE Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Recientemente se viene formando un nuevo plano arqueológico del de- partamento de Petén en Guatemala, una de las zonas más importantes para el estudio de la cultura maya prehispánica. Las amplias zonas que aŭn no han sido reconocidas en la bŭsqueda del asentamiento arqueológico dejan entrever grandes lagunas y muestran abiertamente que nos falta mucho por conocer de este territorio antes de exponer modelos teóricos que conduzcan hacia inter- pretaciones conclusivas acerca del asentamiento y el consecuente urbanismo Maya, con lo cual la mejor táctica es la cautela y el planteamiento objetivo de la información. La actividad de reconocimiento arqueológico llevada a cabo durante la pasa- da década en las Tierras Bajas de Petén y Belice ha demostrado que el tipo de asentamiento que caracteriza al territorio es uno que refiere a m ŭltiples nŭcleos, muy diferente a aquel que por lo general se ha presentado con base en las ciuda- des mayores bien estructuradas que dominaban amplias zonas periféricas com- puestas por asentamientos de composición dispersa, en donde no existían otros nŭcleos que pudieran ser considerados como urbanos. Aunque algunos investigadores prefieren pensar que este nuevo fenómeno de asentamiento está ligado solamente con zonas consideradas periféricas, lo cierto es que la extraordinaria dispersión y la propia estructura intema de las poblacio- nes que se desarrollan en tales áreas periféricas apuntan más bien hacia un fenó- meno específico dentro de la organización politica y social que define a tales re- giones desde el asentamiento formativo. -

Altun Ha and the Water Scroll Emblem Glyph

Ancient Mesoamerica, 29 (2018), 113–135 Copyright © Cambridge University Press, 2018 doi:10.1017/S0956536117000256 KINGS OF THE EAST: ALTUN HA AND THE WATER SCROLL EMBLEM GLYPH Christophe Helmke,a Stanley P. Guenter,b and Phillip J. Wanyerkac aInstitute of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, Karen Blixens Plads 8, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark bFoundation for Archaeological Research and Environmental Studies, 164 W 400 N, Rupert, Idaho 83350 cDepartment of Criminology, Anthropology, and Sociology, Cleveland State University, 2121 Euclid Ave. RT 932, Cleveland, Ohio 44115 ABSTRACT The importance of emblem glyphs to Maya studies has long been recognized. Among these are emblems that have yet to be conclusively matched to archaeological sites. The Water Scroll emblem glyph is one such example, although it appears numerous times in the Classic Maya written corpus between the sixth and the eighth centuries. These many references are found at a variety of sites across the lowlands, attesting to the importance of this ancient kingdom and the kings who carried this title. In the present paper, we review the epigraphic and archaeological evidence and propose that this may be the royal title of the kings who reigned from Altun Ha, in the east central Maya lowlands, in what is now Belize. In so doing, we also begin to reconstruct the dynastic history of the Water Scroll kings, from the vantage of both local and foreign sources. INTRODUCTION transport and trade inland to the central lowlands. This connection is made clear in the realm of ceramics, for many of the Late In 1965, while excavating at the northern Belizean site of Altun Ha, Classic forms and decorative modes found at Altun Ha are identical David M. -

Human Ecology, Agricultural Intensification and Landscape

HUMAN ECOLOGY, AGRICULTURAL INTENSIFICATION AND LANDSCAPE TRANSFORMATION AT THE ANCIENT MAYA POLITY OF UXBENKÁ, SOUTHERN BELIZE by BRENDAN JAMES CULLETON A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2012 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Brendan James Culleton Title: Human Ecology, Agricultural Intensification and Landscape Transformation at the Ancient Maya Polity of Uxbenká, Southern Belize This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Douglas J. Kennett, Ph.D. Chairperson Jon M. Erlandson, Ph.D. Member Madonna L. Moss, Ph.D. Member Patrick Bartlein, Ph.D. Member Keith M. Prufer, Ph.D. Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2012 ii © 2012 Brendan James Culleton iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Brendan James Culleton Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology March 2012 Title: Human Ecology, Agricultural Intensification and Landscape Transformation at the Ancient Maya Polity of Uxbenká, Southern Belize Identifying connections between land use, population change, and natural and human-induced environmental change in ancient societies provides insights into the challenges we face today. This dissertation presents data from archaeological research at the ancient Maya center of Uxbenká, Belize, integrating chronological, geomorphological, and settlement data within an ecological framework to develop methodological and theoretical tools to explore connections between social and environmental change or stability during the Preclassic and Classic Period (~1000 BC to AD 900). -

Ceiba Giant Conical Spines at Copan, 2012

Giant Conical Spines Giant Conical Spines Eco-lodge Hacienda San Lucas Why it is important for Mayanists to Copan Ruinas, Honduras have a good photographing reference archive on trees with conical spines Background of research I have been looking for conical Guatemala (though it is listed as a on Maya ethnobotany: spines of ceiba trees over the last giant and common tree in Parker’s several decades. This is because book on Trees of Guatemala, This is a report on the remarkable Ceiba pentandra trees on many Preclassic, Early Classic, 2008:282). Hura is even called the Hacienda San Lucas, about 3 km from Copan Ruinas, Late Classic and Post Classic Maya Ceiba in South America. Honduras. incense burners and some burial urns are decorated with conical Another fact to consider is that Hura I have been studying plants of Guatemala intensely for spines. These conical spines on the is one of the most poisonous trees of the past five years, and studying plants of Guatemala as Maya ceramic effigies and bowls Mesoamerica. The pre-Columbian an avocation during the previous 45 years. I lived at Tikal are clearly modeled after the spines cultures were adept at utilizing any for 12 months at age 19 (1965). A decade later I created on the Ceiba pentandra tree. plant with noxious or psychoactive the Parque Nacional Yaxha Sacnab while 30-something of chemical components. We know age. It took five years to protect the Yaxha area and get it Although this long-range study of from Thomas Gage that the Maya named a national park. -

The Prehistory of Belizelhammond Mon Down to the 10 M

The Prehistoryof Belize NorrnanHammond Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey Belize, CentralAmerica, has been the location of manyinnovative research projects in Maya archaeology.Over the past generationseveral problem-ori- entedprojects have contributedsignificantly to a new understandingof an- cient Maya subsistenceand settlement,and increasedthe knowntime span of Maya culture.An historicalreview of researchin Belize is followed by a resumeof the currentstate of knowledgeand an indicationoffuture research potential. Introduction in which flow the major perennial rivers, the Hondo and Belize, a small nation on the Caribbeancoast of Central Nuevo, and the smaller Freshwater Creek. The Hondo America, occupies part of the territoryin which the Maya is one of the principal rivers of the Maya lowland zone civilization flourished during the 1st millennium A.C., and has a basin draining northernPeten and part of south- with an apogee in the Classic Period of 250-900 A.C. ern Campeche, an area often dubbed the "Maya Heart- The political history of Belize over the past 200 years land" and containing major sites such as Tikal; the river as a British colony (known until 1973 as British Hon- has throughoutMaya prehistory acted as a corridor to the duras), and now as an independent nation, has engen- Caribbean. Several large lagoons interrupt the courses dered a history of archaeological research distinct from of the Nuevo and Freshwater Creek, and were foci of that in the Spanish-speaking countries that comprise the ancient Maya settlement. The coast of northern Belize remainder of the Maya area (Mexico, Guatemala, Hon- is swampy, with mangrove stands building seawards, and duras, El Salvador).