The Linguistics of Toponymy in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashes to Caches: Is Dust Dust Among the Heterarchichal Maya?

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Anthropology & Sociology Faculty Publications Anthropology & Sociology 6-2020 Ashes to Caches: Is Dust Dust Among the Heterarchichal Maya? Marshall Joseph Becker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/anthrosoc_facpub Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Volume 28, Issue 3 June 2020 Welcome to the “28 – year book” of The Codex. waxak k’atun jun tun hun Now in its 28th year, The Codex continues to publish materials of substance in the world of Pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican studies. We continue that tradition in this issue. This new issue of The Codex is arriving during a pandemic which has shut down all normal services in our state. Rather than let our members and subscribers down, we decided to go digital for this issue. And, by doing so, we NOTE FROM THE EDITOR 1 realized that we could go “large” by publishing Marshall Becker’s important paper on the ANNOUNCEMENTS 2 contents of caches in the Maya world wherein he calls for more investigation into supposedly SITE-SEEING: REPORTS FROM THE “empty” caches at Tikal and at other Maya sites. FIELD: ARCHAEOLOGY IN A GILDED AGE: THE UNIVERSITY OF Hattula Moholy-Nagy takes us back to an earlier PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM’S TIKAL era in archaeology with her reminiscences of her PROJECT, 1956-1970 days at Tikal in the 1950s and 1960s. Lady by Sharp Tongue got her column in just before the Hattula Moholy-Nagy 3 shut-down happened, and she lets us in on some secrets in Lady K’abal Xook’s past at her GOSSIP COLUMN palace in Yaxchilan. -

Edwin M. Shook Archival Collection, Guatemala City, Guatemala

FAMSI © 2004: Barbara Arroyo and Luisa Escobar Edwin M. Shook Archival Collection, Guatemala City, Guatemala Research Year: 2003 Culture: Maya Chronology: Pre-Classic to Post Classic Location: Various archaeological sites in Guatemala and México Site: Tikal, Uaxactún, Copán, Mayapán, Kaminaljuyú, Piedras Negras, Palenque, Ceibal, Chichén Itzá, Dos Pilas Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Background Project Priorities Conservation Issues Guide to the Edwin M. Shook Archive Site Records Field Notes Photographs Correspondence and Documents Illustrations Maps Future Work Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract The Edwin M. Shook archive is a collection of documents that resulted from Dr. Edwin M. Shook’s archaeological fieldwork in Mesoamerica from 1934-1998. He came to Guatemala as part of the Carnegie Institution and carried out investigations at various sites including Tikal, Uaxactún, Copán, Mayapán, among many others. He further established his residence in Guatemala where he continued an active role in archaeology. The archive donated by Dr. Shook to Universidad del Valle de Guatemala in 1998 contains his field notes, Guatemala archaeological site records, photographs, documents, and illustrations. They were stored at the Department of Archaeology for several years until we obtained FAMSI’s support to start the conservation and protection of the archive. Basic conservation techniques were implemented to protect the archive from further damage. This report lists several sets of materials prepared by Dr. Shook throughout his fieldwork experience. Through these data sets, people interested in Shook’s work can know what materials are available for study at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala. Resumen El archivo Edwin M. Shook consiste en una colección de documentos que resultaron de las investigaciones arqueológicas en Mesoamérica realizadas por el Dr. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

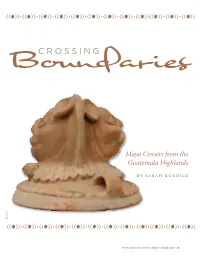

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Canuto-Et-Al.-2018.Pdf

RESEARCH ◥ shows field systems in the low-lying wetlands RESEARCH ARTICLE SUMMARY and terraces in the upland areas. The scale of wetland systems and their association with dense populations suggest centralized planning, ARCHAEOLOGY whereas upland terraces cluster around res- idences, implying local management. Analy- Ancient lowland Maya complexity as sis identified 362 km2 of deliberately modified ◥ agricultural terrain and ON OUR WEBSITE another 952 km2 of un- revealed by airborne laser scanning Read the full article modified uplands for at http://dx.doi. potential swidden use. of northern Guatemala org/10.1126/ Approximately 106 km science.aau0137 of causeways within and .................................................. Marcello A. Canuto*†, Francisco Estrada-Belli*†, Thomas G. Garrison*†, between sites constitute Stephen D. Houston‡, Mary Jane Acuña, Milan Kováč, Damien Marken, evidence of inter- and intracommunity con- Philippe Nondédéo, Luke Auld-Thomas‡, Cyril Castanet, David Chatelain, nectivity. In contrast, sizable defensive features Carlos R. Chiriboga, Tomáš Drápela, Tibor Lieskovský, Alexandre Tokovinine, point to societal disconnection and large-scale Antolín Velasquez, Juan C. Fernández-Díaz, Ramesh Shrestha conflict. 2 CONCLUSION: The 2144 km of lidar data Downloaded from INTRODUCTION: Lowland Maya civilization scholars has provided a unique regional perspec- acquired by the PLI alter interpretations of the flourished from 1000 BCE to 1500 CE in and tive revealing substantial ancient population as ancient Maya at a regional scale. An ancient around the Yucatan Peninsula. Known for its well as complex previously unrecognized land- population in the millions was unevenly distrib- sophistication in writing, art, architecture, as- scape modifications at a grand scale throughout uted across the central lowlands, with varying tronomy, and mathematics, this civilization is the central lowlands in the Yucatan peninsula. -

Leyenda De Los Soles) to Explain Maya Creations

Why we use the Aztec Myth (Leyenda de los Soles) to Explain Maya Creations The surviving accounts of the Maya Creation Myth are fragments, tatters. Much more is missing than is there. The earliest surviving fragments appear on the monuments of Izapa (and neighbors) and the newly‐ discovered Murals of San Bartolo (ca. 100 BCE). As if through a keyhole, we glimpse a rich, intricate cosmology connecting time, space and personalities. It relates the cardinal directions to colors, species of trees and game, the calendar, myths, and who knows what else. Eight centuries later, Classic Maya vase painters illustrate a few other Mythic scenes, some involving the Hero Twins. A few Classic stone inscriptions connect Creation with house‐building. Six centuries later, one of the curiosities Cortez presented to the Emperor, a book we call the Dresden Codex, recounts several arcane events which occurred on 4 Ajaw 8 Kumk’u. Later still, a Quiché Maya scribe in the impoverished and conquered Guatemalan highlands copied out the Popol Vuh, connecting his cacique’s ancestors back to the Creations of the World (ca. 1700). It dwells on the Hero Twins, who prepared the world for its final Creation ‐ our Creation. Though it is clear that the Maya conceived a dizzying, intricately interconnected cosmology, we have difficulty working out its details. This is partly due to the fragmentary nature of our evidence, but it is also increasingly clear that the stories varied substantially from city‐state to city‐state. (Not unlike the conflicting versions of Abraham’s Sacrifice: In the Biblical version, the son is Isaac, who goes on to father the Israelites. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ceramics of Lubaantun: Stasis and Change in the Southern Belize Region during the Late and Terminal Classic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6zf41162 Author Irish, Mark David Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Ceramics of Lubaantun: Stasis and Change in the Southern Belize Region during the Late and Terminal Classic A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Mark David Irish Committee in charge: Professor Geoffrey E. Braswell, Chair Professor Paul S. Goldstein Professor Thomas E. Levy 2015 Copyright Mark David Irish, 2015 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Mark David Irish is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii DEDICATION In recognition of all of the support they have given me throughout my years of education; for proof-reading countless essays and the source of endless amounts of constructive criticism; for raising me to value learning and the pursuit of knowledge; for always being there when I needed someone to talk to; this thesis is dedicated to my family, including my mother Deanna, my father John, my sister Stephanie, and my wonderful wife Karla. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………..…. iii Dedication…………………………………………………………………………….. iv Table of Contents……………………………………………………………………… v List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………. vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………….... vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………. viii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Background…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 The Southern Belize Region…………………………………………………… 12 History of Lubaantun…………………………………………………………. -

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: the Holmul Region Case

Prehistoric Human-Environment Interactions in the Southern Maya Lowlands: The Holmul Region Case Final Report to the National Science Foundation 2010 Submitted by: Francisco Estrada-Belli and David Wahl Introduction Dramatic population changes evident in the Lowland Maya archaeological record have led scholars to speculate on the possible role of environmental degradation and climate change. As a result, several paleoecological and geochemical studies have been carried out in the Maya area which indicate that agriculture and urbanization may have caused significant forest clearance and soil erosion (Beach et al., 2006; Binford et al., 1987; Deevey et al., 1979; Dunning et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2002; Jacob and Hallmark, 1996; Wahl et al., 2007). Studies also indicate that the late Holocene was characterized by centennial to millennial scale climatic variability (Curtis et al., 1996; Hodell et al., 1995; Hodell et al., 2001; Hodell et al., 2005b; Medina-Elizalde et al., 2010). These findings reinforce theories that natural or anthropogenically induced environmental change contributed to large population declines in the southern Maya lowlands at the end of the Preclassic (~A.D. 200) and Classic (~A.D. 900) periods. However, a full picture of the chronology and causes of environmental change during the Maya period has not emerged. Many records are insecurely dated, lacking from key cultural areas, or of low resolution. Dating problems have led to ambiguities regarding the timing of major shifts in proxy data (Brenner et al., 2002; Leyden, 2002; Vaughan et al., 1985). The result is a variety of interpretations on the impact of observed environmental changes from one site to another. -

Central America

Zone 1: Central America Martin Künne Ethnologisches Museum Berlin The paper consists of two different sections. The first part has a descriptive character and gives a general impression of Central American rock art. The second part collects all detailed information in tables and registers. I. The first section is organized as follows: 1. Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies 2. Known Sites: modes of iconographic representation and geographic context 3. Chronological sequences and stylistic analyses 4. Documentation and Known Sites: national inventories, systematic documentation and most prominent rock art sites 5. Legislation and institutional frameworks 6. Rock art and indigenous groups 7. Active site management 8. Conclusion II. The second section includes: table 1 Archaeological chronologies table 2 Periods, wares, horizons and traditions table 3 Legislation and National Archaeological Commissions table 4 Rock art sites, National Parks and National Monuments table 5 World Heritage Sites table 6 World Heritage Tentative List (2005) table 7 Indigenous territories including rock art sites appendix: Archaeological regions and rock art Recommended literature References Illustrations 1 Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies: Central America, as treated in this report, runs from Guatemala and Belize in the north-west to Panama in the south-east (the northern Bridge of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan peninsula are described by Mr William Breen Murray in Zone 1: Mexico (including Baja California)). The whole region is characterized by common geomorphologic features, constituting three different natural environments. In the Atlantic east predominates extensive lowlands cut by a multitude of branched rivers. They cover a karstic underground formed by unfolded limestone. -

Zachary Nelson

FAMSI © 2008: Zachary Nelson Satellite Survey of El Zotz, Guatemala Research Year: 2007 Culture: Maya Chronology: Pre-Classic through Terminal Classic Location: Petén, Guatemala Sites: El Zotz, El Diablo, Las Palmitas, El Palmar Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Objectives Methods and Findings El Zotz Mapping Las Palmitas El Diablo El Palmar Conclusions Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Zachary Nelson Brigham Young University [email protected] -1- Abstract IKONOS satellite imagery is not a cure-all for effective canopy penetration in Petén, Guatemala. It failed to distinguish between sites and natural features at El Zotz, Guatemala. Various types of data manipulation failed to provide sufficient penetrating power. This suggests that micro-environmental factors may be at work, and a pan- Petén process is still in the future. Ground survey of the El Zotz region included mapping at subsidiary sites. Las Palmitas (North Group) has a pyramid with a standing room complete with ancient and modern graffiti. El Diablo (West Group) was mapped. El Palmar, near a cival or residual lake, is configured in an “E-Group” pattern similar to astronomical features identified at Uaxactún. Resumen Las imágenes de satélite de tipo IKONOS todavía no sirven en todo el Petén para penetrar la selva. En El Zotz, las imágenes no pudieron distinguir entre edificios y selva aun con manipulación digital. Eso quiere decir que éxito puede ser un resultado de factores micro-ambiental y todavía no hemos logrado un sistema que siempre funciona. Mapeo de pie en la región alrededor de El Zotz incluyó elaboración de mapas de sitios pequeños. -

Martin Künne Y Matthias Strecker INTRODUCCION De Todas Las Manifestaciones Culturales Que Han Dejado Los Indígenas De México

Martin Künne y Matthias Strecker INTRODUCCION De todas las manifestaciones culturales que han dejado los indígenas de México y de América Central, los grabados y pinturas rupestres han recibido la menor atención. Aunque las representaciones rupestres pertenecen a los monumentos arqueológicos más visibles, solo raras veces se las incluyó en investigaciones sistemáticas. Desde los primeros informes y noticias de la mitad del siglo XIX se dejó su documentación a menudo a aficionados e investigadores autodidactas. De la misma manera se nota que tampoco la literatura especializada actual toma en cuenta las representaciones rupestres de la región. A pesar de que el recién editado "Handbook of Rock Art Research" (Whitley 2001) comprende cuatro regiones americanas, faltan completamente Mesoamérica y América Central. Por otro lado podemos constatar que muchas documentaciones e informes sobre el arte rupestre centroamericano han sido parciales y hacen difícil una visión del conjunto. Sus enfoques se limitan normalmente a perspectivas descriptivas. Solamente algunas tienen también carácter analítico (A. Stone 1995). Entre los pocos compendios que mencionan representaciones rupestres de México y de América Central están las publicaciones "Rock Art Studies: News of the World I" (Bahn y Fossati 1996) y "Arte Prehistórico de América" (Schobinger 1997). Nuestro libro tiene carácter bibliográfico. Su propósito es ser una guía para la búsqueda de fuentes de información y ofrecer una introducción al estudio sistemático del arte rupestre en el oriente de México y en Centroamérica; ampliando y actualizando la publicación anterior "Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America" (Strecker 1979). Se dirige tanto a especialistas, estudiantes y aficionados como a propietarios o indígenas quienes asuman el rol de "custodios naturales" de sitios con representaciones rupestres.