Freemasonry in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

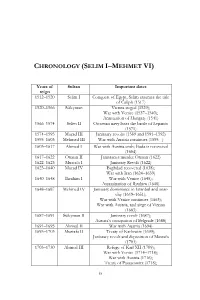

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

553098 (1).Pdf

T.C. ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ TÜRK İNKILÂP TARİHİ ENSTİTÜSÜ CUMHURİYET HALK PARTİSİ VİLAYET/İL KONGRELERİNİN PARTİ POLİTİKALARINA ETKİLERİ (1930-1950) Doktora Tezi Sezai Kürşat ÖKTE Ankara-2019 T.C. ANKARA ÜNİVERSİTESİ TÜRK İNKILÂP TARİHİ ENSTİTÜSÜ CUMHURİYET HALK PARTİSİ VİLAYET/İL KONGRELERİNİN PARTİ POLİTİKALARINA ETKİLERİ (1930-1950) Doktora Tezi Öğrencinin Adı Sezai Kürşat ÖKTE Tez Danışmanı Prof. Dr. Temuçin Faik ERTAN Ankara-2019 ÖZET Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi, 9 Eylül 1923’te Türkiye’de cumhuriyetin ilanından hemen önce kurulmuş ve 1923-1950 yılları arasında 27 yıl süreyle iktidarda kalmıştır. Cumhuriyet dönemi başlangıcında ve 1945-1946 yılları arasında çok partili siyasal hayata geçişte önemli bir rol oynayan CHP; ülke yönetimini 1950’de Demokrat Parti’ye devretmiştir. Dolayısıyla CHP, Türk Siyasi Tarihi’nin bu sürecinde; ülkede yaşanan siyasal, sosyal, iktisadi ve kültürel bütün gelişmelerin yönlendiricisi olmuştur. Türkiye Siyaseti’nde böyle önemli bir konuma sahip olmakla beraber, kendi iktidarından sonra yaşanan siyasal gelişmeleri, kurulan siyasal parti ve kurumları da etkilemiştir. Bu nedenle Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Tarihi üzerine yapılan birçok araştırmanın da başlangıcında ve günümüze kadar gelen süreçte, CHP bir şekilde yer almış, halen de almaktadır. Bu çalışmada; 1930-1950 yılları arasında, Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi’ne bağlı vilayet örgütlerinin, düzenlemiş oldukları kongrelerde görüşülüp, karara bağlanan ve parti merkez yönetimine iletilen hususların, parti politikalarına etkisinin olup olmadığı incelenmiştir. Çalışmanın temel -

Mustafa ÖZYÜREK Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nin İlk Maliye Bakanı

Mavi Atlas, 7(2)/2019: 265-274 Araştırma Makalesi | Research Article Makale Geliş | Received: 19.09.2019 Makale Kabul | Accepted: 04.10.2019 DOI: 10.18795/gumusmaviatlas.622245 Mustafa ÖZYÜREK Dr. Öğr. Üyesi| Assist. Prof. Dr. Iğdır Üniversitesi, Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi, Tarih Bölümü, Iğdır, TÜRKİYE Igdir University, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of History, Igdir, TURKEY ORCID: 000-0001-5426-9775 [email protected] Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nin İlk Maliye Bakanı Gümüşhane Milletvekili Hasan Fehmi Ataç’ın Mali Alandaki Faaliyetleri Öz 1879’da Gümüşhane’de doğan Hasan Fehmi Bey, başladığı ilk ve orta öğrenimini İstanbul’da tamamlamıştır. Çeşitli görevlerde bulunduktan sonra Osmanlı Mebusan Meclisinde 18 Nisan 1912-5 Ağustos 1912 ile 15 Şubat 1913-21 Aralık 1918 tarihleri arasında iki dönem Gümüşhane mebusluğu yapmıştır. Daha sonra Ankara’ya geçerek Mustafa Kemal Paşa’nın yanında Millî Mücadeleye katılmıştır. Türk siyasi hayatında çok önemli bir yere sahip olan Hasan Fehmi Ataç’ın en önemli hizmeti kuşkusuz Millî Mücadele Dönemi’nde 19 Mayıs 1921-9 Temmuz 1922 tarihleri arasında yaptığı maliye vekilliğidir. Çünkü devletin kısıtlı gelirlerine rağmen Türk ordusunun hemen hemen bütün ihtiyaçlarını karşılamayı başarmıştır. Doğu ve Batı orduları için iki ayrı defterdarlık kurarak subay maaşlarının düzenli olarak ödenmesini sağlamış, ayrıca Büyük Taarruz’un finans kaynaklarını temin ve organize etmiştir. Hasan Fehmi Bey, Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisinin açılmasından itibaren ilk sekiz dönem boyunca Gümüşhane milletvekilliği yapmıştır. 1 Kasım 1923-2 Ocak 1924 tarihleri arasında cumhuriyet tarihinin ilk maliye vekilliği görevinde bulunmuş, daha sonra 1924-1925 yıllarında ise ziraat vekilliği yapmıştır. Sonraki yıllarda anayasa, bütçe ve maliye komisyonlarında görev almış ve 1961’de vefat etmiştir. -

Birinci Dönem Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi'nde Amasya Milletvekilleri

T.C. NİĞDE ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI BİRİNCİ DÖNEM TÜRKİYE BÜYÜK MİLLET MECLİSİ’NDE AMASYA MİLLETVEKİLLERİ VE SİYASİ FAALİYETLERİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ HAZIRLAYAN Tolgahan KARAİMAMOĞLU Niğde Haziran, 2016 T.C. NİĞDE ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI BİRİNCİ DÖNEM TÜRKİYE BÜYÜK MİLLET MECLİSİ’NDE AMASYA MİLLETVEKİLLERİ VE SİYASİ FAALİYETLERİ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ HAZIRLAYAN Tolgahan KARAİMAMOĞLU Danışman :Doç. Dr. Nevzat TOPAL Üye : Doç. Dr. Hamdi DOĞAN Üye : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Seyhun ŞAHİN Niğde Haziran, 2016 iii i ii ÖNSÖZ Yüksek lisans tezi olarak hazırlanan, ‘’Birinci Dönem Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi’nde Amasya Milletvekilleri ve Siyasi Faaliyetleri’’ isimli bu çalışmamızda, Meclisin Birinci Dönemi’nde (23 Nisan 1920–16 Nisan 1923) Amasya Milletvekilleri ve faaliyetleri konu edilmiştir. Çalışmamız dört bölümden oluşmakta olup birinci bölümde; Mili Mücadele Döneminde, Amasya ve çevresinde meydana gelen olaylar değerlendirilmiştir. İkinci bölümde; TBMM’nin açılışı, Amasya yapılan seçim hazırlıkları, seçimlerin yapılması ve Birinci Meclisin genel durumu değerlendirilmiştir. Üçüncü bölümde; Amasya’dan seçilen beş milletvekili ile Osmanlı Mebuslar Meclisi’nden katılan iki milletvekilinin biyografileri verilmiştir. Dördüncü ve son bölümde ise Amasya milletvekillerinin Meclisteki çalışmaları ve faaliyetleri anlatılmıştır. Mondros Mütarekesi sonrası yapılan işgallere karşı teşkilatlanarak başarılı bir mücadele sergileyen ve tamamen “Milli Hakimiyete” dayalı yeni bir devlet kuran Birinci Meclisin Türkiye Cumhuriyeti tarihinde önemli bir yeri vardır. Bu çalışma ile Birinci Mecliste bulunan Amasya Milletvekillerinin kısa biyografileri verilerek yaptıkları faaliyetler incelenmiştir. Çalışma konumuz gereği Meclis Zabıt Cerideleri, Gizli Celse Zabıtları, Milletvekillerinin Kişisel Dosyaları, Nutuk temel başvuru kaynaklarımız olmuştur. Bunun dışında TBMM tarafından yayınlanan Meclis Albümleri vb. çalışmalar ile Milli Mücadele ve TBMM’ne iştirak edenler tarafından yazılan hatıralardan da istifade edilmiştir. -

The Political Ideas of Derviş Vahdeti As Reflected in Volkan Newspaper (1908-1909)

THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) by TALHA MURAT Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University AUGUST 2020 THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) Approved by: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel . (Thesis Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Ayşe Ozil . Assist. Prof. Fatih Bayram . Date of Approval: August 10, 2020 TALHA MURAT 2020 c All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) TALHA MURAT TURKISH STUDIES M.A. THESIS, AUGUST 2020 Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel Keywords: Derviş Vahdeti, Volkan, Pan-Islamism, Ottomanism, Political Islam The aim of this study is to reveal and explore the political ideas of Derviş Vahdeti (1870-1909) who was an important and controversial actor during the first months of the Second Constitutional Period (1908-1918). Starting from 11 December 1908, Vahdeti edited a daily newspaper, named Volkan (Volcano), until 20 April 1909. He personally published a number of writings in Volkan, and expressed his ideas on multiple subjects ranging from politics to the social life in the Ottoman Empire. His harsh criticism that targeted the policies of the Ottoman Committee of Progress and Union (CUP, Osmanlı İttihâd ve Terakki Cemiyeti) made him a serious threat for the authority of the CUP. Vahdeti later established an activist and religion- oriented party, named Muhammadan Union (İttihâd-ı Muhammedi). Although he was subject to a number of studies on the Second Constitutional Period due to his alleged role in the 31 March Incident of 1909, his ideas were mostly ignored and/or he was labelled as a religious extremist (mürteci). -

The Conversion of the Jews and the Islamization of Jewish Spaces During the First Centuries of the Ottoman Empire’

BAHAR, Beki L. ‘The conversion of the Jews and the islamization of Jewish spaces during the first centuries of the Ottoman empire’. Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora. Raniero Speelman, Monica Jansen & Silvia Gaiga eds. ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA 7. Utrecht : Igitur Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978‐90‐6701‐032‐0. SUMMARY This essay by the late Beki L. Behar (z.l.) focuses on conversion to Islam until the end of the Seventeenth Century. If we can speak of a privileged treatment of the Jews in the reigns of Mehmet Fatih, Bayezit II, Süleyman and Selim II – the period of Gracia Mendez and Josef Nasi –, Mehmet IV’s reign (1648‐1687) was marked by lack of tolerance and the Islamic fanatism of the fundamentalist Kadezadeli sect, in which period Jews had to face all sorts of prohibition and forced conversion, sometimes losing their living quarters. Although the Jews as inhabitants of cities rather than villages were generally not subjected to conversion and were not encouraged to enter upon the career at Court known as devşirme, an important wave of conversions initiated with Shabtai Zwi (Sabbatai Zevi), the false mashiah who preferred Islam to death penalty. His numerous followers are known in Turkish as dönmeler (dönmes). Other conversions had a less dramatic background, such as divorcing under Shari’a law or for convenience’s sake. A famous case is the court fysician Moshe ben Raphael Abravanel, who became Muslim in order to be able to practise. KEYWORDS Conversion, Shabtai Zwi, dönmes, Islamization The authors The proceedings of the international conference Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora (Istanbul, June 23‐27 2010) are volume 7 of the series ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

Atatürk Dönemi Maliye Politikaları

T.C. MALİYE BAKANLIĞI ATATÜRK DÖNEMİ MALİYE POLİTİKALARI 29 Ekim 2008 i T.C. MALİYE BAKANLIĞI Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı Yayın No: 2008/384 www.sgb.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Her hakkı Maliye Bakanlığı Strateji Geliştirme Başkanlığı’na aittir. Kaynak gösterilerek alıntı yapılabilir. ISBN: 978-975-8195-22-0 1000 Adet Ankara, 2008 Bu Eser, Cumhuriyetimizin 85. Yılı Anısına, Maliye Bakanlığı adına Prof.Dr. Güneri AKALIN tarafından hazırlanmıştır. Eserde yeralan görüş ve yorumlar yazara aittir. Tasarım: İvme Tel: 0312 230 67 01 Baskı: Ümit Ofset Matbaacılık Tel: 0312 384 26 27 ii SUNUŞ İnsanlar ve milletler geleceği şekillendirmek için tarihi geçmişlerini, kültür ve medeniyetlerini asla unutmamalıdır. Bizi daha ileriye götürecek bu birikimlerimizdir. Bu birikimler, birey ve toplumlarda mensubiyet bilincini canlı tutar ve onu derinleştirir. Toplumlar zaman içinde hep var oldukları ve var olacakları duygusuna ancak tarih bilinci ile ulaşabilirler. Tarih bilincinden yoksun olan toplumlar ise zaman içinde geri kalmaya ve nihayetinde yok olmaya mahkumdurlar. Tarih bilinci dar bir bakış açısıyla oluşturulamaz. Bu bilinç, tarihi olayları, eserleri ve şahsiyetleri geleceğe ışık tutacak şekilde yorumlamakla oluşur. Cumhuriyet tarihimizin kuşkusuz en önemli aşaması olan Gazi Mustafa Kemal Atatürk dönemini de bu şekilde ele almalıyız. Kurtuluş Savaşı sona erdiğinde, Türk milleti tam anlamıyla yorgun, bitkin ve yoksul düşmüştü. Savaş zaten sınırlı olan kaynakları tamamen tüketmişti. Bu şartlar altında bir devletin ancak mali temeller üzerinde kurulabileceğinin farkında olan Büyük Önder Atatürk, savaş biter bitmez mali bağımsızlığın kazanılması mücadelesini başlatmıştı. Bu süreçte Atatürk, Maliye politikamızın yerini ve işlevini yeniden tanımlamış, ekonomik kalkınmada maliyenin rolüne büyük önem vermiştir. “Atatürk Dönemi Maliye Palitikaları” çalışmasında, Atatürk dönemi bir bütün olarak ele alınırken mali kurumlar ayrıştırılarak incelenmiştir. -

SABATAYCILIK SALTANATI VE MEŞHUR DÖNMELER - Milli Çözüm Dergisi

SABATAYCILIK SALTANATI VE MEŞHUR DÖNMELER - Milli Çözüm Dergisi Yazar Milli Çözüm Dergisi 26 Temmuz 2012 Birçok internet sitesinde yıllardır yayınlandığı ve hiç kimsenin yalanlama ihtiyacı duymadığı,“Sabataist Müslüman görünümlü gizli Yahudi”leri, tekrar gündeme getirmek, asılsız iddia ve iftiralar varsa, ilgililere bunları düzeltme imkanı vermek; ve şahısları deşifre edip hedef göstermek gibi bayağı ve aşağı bir fesatlıktan uzak; ülkemizin, devletimizin ve milletimizin muhatap olduğu bir tehdide dikkat çekmek üzere bu konuya değinmeyi münasip gördük. Bilinen bazı “Selanik Dönmeleri” (“Sabataycılar” veya “Gizli Yahudiler”) Bu listenin dayandığı kaynak: ( http://www.sabetay.50g.com/Liste/liste.html ) internette bulduğum en geniş DÖNME listesiydi. Fakat 28 Şubat’ın (1997) meşhur isimlerini bu listede göremedim: Org. Çevik Bir (28 Şubatın mimarlarından), Güven Erkaya Deniz Komutanı (28 Şubatın mimarlarından), Kemal Gürüz YÖK Başkanı, Prof. Kemal Alemdaroğlu İ.Ü Eski Rektörü, Prof. Nur Sertel gibilerinin de Sebataist olduğu belirtilmekteydi. 28 Şubat sonrasına dikkat edelim. Ordu’dan en çok İRTİCACI subay ve öğrenci atılması 28 Şubat’ın ilk yıllarında gözlendi, Üniversiteler İRTİCACI’lardan temizlendi. Daha evvelden imam hatiplerde, üniversitelerde başörtüsü ile okunabilirken, bu tarihten sonra bu hak engellendi. İmam Hatiplerin pratikte önü kesildi. Yükselen Anadolu sermayesinin önü kesildi. (Cüneyt Ülsever’e göre, 28 Şubatın asıl sebebi bu sermaye meselesiymiş). 28 Şubatın planları Deniz Kuvvetlerinin Gölcük’teki merkezinde yapıldı deniyor. Bu merkez 1999 Gölcük depreminde denize gömüldü. Rasathaneden Prof. Işıkara depremin merkez üssünün “tam deniz kuvvetleri merkezi” olduğunu söylemişti. Yakın geçmişteki bir Genel Kurmay Başkanımızın dönme olduğu vurgulanıyor. 2-3 defa nüfus kütüğünü bir şehirden başka şehre taşıdığı, izini kaybettirmek için yaptığı söyleniyor. “Türkler 1.500.000 ermeni öldürdü” deyip, derhal Nobel’i alan Orhan Pamuk’u da unutmamak gerekiyor. -

ENVIRONMENT of CULTURE and ART in the OTTOMAN EMPIRE in 19Th CENTURY

The Online Journal of Science and Technology - April 2018 Volume 8, Issue 2 ENVIRONMENT OF CULTURE AND ART IN THE OTTOMAN th EMPIRE IN 19 CENTURY Nesli Tuğban YABAN Baskent University, Department of Public Relations and Publicity, Ankara-Turkey [email protected] Abstract: Westernisation and modernisation of the Ottoman Empire began to burgeon in the 17th century; it became evident in the 18th century and the 19th century witnessed the most intense interaction and the exact reconstruction process. New way of living which was originated in Europe and representatives thereof became influential as guides and determinants of reconstruction process in the Ottoman Empire. It is possible to point out that the Ottoman Empire which got closer to France for handling military problems, to England for industrialisation purposes and to Italy for architecture and arts had intense communication and the resulting interaction with European states in the course of reconstruction process. This study aims to give information about the social, cultural and artistic environment in the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876-1909). Key Words: Culture, Art, Ottoman Empire, Sultan Abdul Hamid II. General View of the Environment of Culture and Art in 19th Century in the Ottoman Empire It is clear that sultans had a very important role in the ruling of the country as a part of state system of the Ottoman Empire thus, good or bad functioning of the state and events and actions which might affect the society from various aspects were closely connected to personality, behaviours and mentality of the sultan. -

List of Freemasons from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation , Search

List of Freemasons From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation , search Part of a series on Masonic youth organizations Freemasonry DeMolay • A.J.E.F. • Job's Daughters International Order of the Rainbow for Girls Core articles Views of Masonry Freemasonry • Grand Lodge • Masonic • Lodge • Anti-Masonry • Anti-Masonic Party • Masonic Lodge Officers • Grand Master • Prince Hall Anti-Freemason Exhibition • Freemasonry • Regular Masonic jurisdictions • Opposition to Freemasonry within • Christianity • Continental Freemasonry Suppression of Freemasonry • History Masonic conspiracy theories • History of Freemasonry • Liberté chérie • Papal ban of Freemasonry • Taxil hoax • Masonic manuscripts • People and places Masonic bodies Masonic Temple • James Anderson • Masonic Albert Mackey • Albert Pike • Prince Hall • Masonic bodies • York Rite • Order of Mark Master John the Evangelist • John the Baptist • Masons • Holy Royal Arch • Royal Arch Masonry • William Schaw • Elizabeth Aldworth • List of Cryptic Masonry • Knights Templar • Red Cross of Freemasons • Lodge Mother Kilwinning • Constantine • Freemasons' Hall, London • House of the Temple • Scottish Rite • Knight Kadosh • The Shrine • Royal Solomon's Temple • Detroit Masonic Temple • List of Order of Jesters • Tall Cedars of Lebanon • The Grotto • Masonic buildings Societas Rosicruciana • Grand College of Rites • Other related articles Swedish Rite • Order of St. Thomas of Acon • Royal Great Architect of the Universe • Square and Compasses Order of Scotland • Order of Knight Masons • Research • Pigpen cipher • Lodge • Corks Eye of Providence • Hiram Abiff • Masonic groups for women Sprig of Acacia • Masonic Landmarks • Women and Freemasonry • Order of the Amaranth • Pike's Morals and Dogma • Propaganda Due • Dermott's Order of the Eastern Star • Co-Freemasonry • DeMolay • Ahiman Rezon • A.J.E.F. -

Can You List and Date the Losses of the Ottoman Empire Between 1683 -1914? the Correct Answer Is (B) False Islamic Principals ( Quran and Hadith ) Was Used To

Egypt , Iran and Turks The Nineteenth Century MES 20 Reflections on the Middle East Prof. Hesham Issa Mohammed Abdelaal History and Conflicts Ottoman (Turkey) I Egypt I Qujar (Iran) I i>Clicker Questions Lecture and Reading Intent outcomes: Concepts in this session Knowledge The era Of Transformation! 1.The decline of the Ottoman Empire:! • Militating against the centralization of state authority! • List the Names of effective persons in the 19th • The westernization of Ottoman Empire. ! • Internal Decays and the Janissaries ! century Turkey, Egypt, Iran. • The French expedition to Egypt ! • Turkey Reform in the 19th century! • Summarize the political reform in the Middle • The Tanzemat! • Young Ottomans and Young Turks! 2.Egypt Reform in the 19th century ! east 19th Century. • Muhammed Ali Pasha Era and the urban reform! • The British Occupation ! • Describe the reasons for the decline of • The Nationalism period ! 3.Iran reforms in the 19th century ! • Change in Iranian Shi’ism after the Safavids and the rise of " Ottoman empire. Qujar density and the Ulama! • The effect of European Imperialism ! Comprehension • The Constitutional Revolution The decline of the Ottoman Empire Can you List and date the Losses of the Ottoman Empire between 1683 -1914? The correct answer is (B) False Islamic principals ( Quran and Hadith ) was used to During the four empires (Umayyad, Abbasid, Ottoman, Safavid) rule. the Caliph in each empire invoked a divine status. A.True B.False Notes of importance to be considered While Watching documentaries •The Reasons for decline •The Relation between Religion and the state. •The European Imperial Intervention •The Political economical and social reform The decline of the Ottoman Empire Egypt Reform in the 19th century ! Mohammed Ali Pasha Era (Ottoman Empire) ! Ottoman (Turkey) I Egypt I Qujar (Iran) I i>Clicker Questions Group Discussion In the nineteenth Century, Ottoman (Turkey) , Egypt, Qujar (Iran), were faced by dramatic change between the challenging slow decline, reform and European Imperial intervention.