The Swedish RAND-36 Health Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS DIVISION OF INSURANCE PRODUCER LICENSING 1000 Washington Street, Suite 810 Boston, MA 02118-6200 FAX (617) 753-6883 http://www.mass.gov/doi Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021 License # Licensure Individual Address City State Zip Phone # 1 007408 01/01/1977 Abate, Andrew Suffolk AutoBody, Inc., 25 Merchants Dr #3 Walpole MA 02081 0-- 0 2 014260 11/24/2003 Abdelaziz, Ilaj 20 Vine Street Lexington MA 02420 0-- 0 3 013836 10/31/2001 Abkarian, Khatchik H. Accurate Collision, 36 Mystic Street Everett MA 02149 0-- 0 4 016443 04/11/2017 Abouelfadl, Mohamed N Progressive Insurance, 2200 Hartford Ave Johnston RI 02919 0-- 0 5 016337 08/17/2016 Accolla, Kevin 109 Sagamore Ave Chelsea MA 02150 0-- 0 6 010790 10/06/1987 Acloque, Evans P Liberty Mutual Ins Co, 50 Derby St Hingham MA 02018 0-- 0 7 017053 06/01/2021 Acres, Jessica A 0-- 0 8 009557 03/01/1982 Adam, Robert W 0-- 0 West 9 005074 03/01/1973 Adamczyk, Stanley J Western Mass Collision, 62 Baldwin Street Box 401 MA 01089 0-- 0 Springfield 10 013824 07/31/2001 Adams, Arleen 0-- 0 11 014080 11/26/2002 Adams, Derek R Junior's Auto Body, 11 Goodhue Street Salem MA 01970 0-- 0 12 016992 12/28/2020 Adams, Evan C Esurance, 31 Peach Farm Road East Hampton CT 06424 0-- 0 13 006575 03/01/1975 Adams, Gary P c/o Adams Auto, 516 Boston Turnpike Shrewsbury MA 01545 0-- 0 14 013105 05/27/1997 Adams, Jeffrey R Rodman Ford Coll Ctr, Route 1 Foxboro MA 00000 0-- 0 15 016531 11/21/2017 Adams, Philip Plymouth Rock Assurance, 901 Franklin Ave Garden City NY 11530 0-- 0 16 015746 04/25/2013 Adams, Robert Andrew Country Collision, 20 Myricks St Berkley MA 02779 0-- 0 17 013823 07/31/2001 Adams, Rymer E 0-- 0 18 013999 07/30/2002 Addesa, Carmen E Arbella Insurance, 1100 Crown Colony Drive Quincy MA 02169 0-- 0 19 014971 03/04/2008 Addis, Andrew R Progressive Insurance, 300 Unicorn Park Drive 4th Flr Woburn MA 01801 0-- 0 20 013761 05/10/2001 Adie, Scott L. -

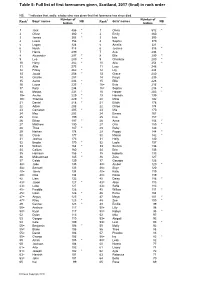

Table 5: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) in Rank Order

Table 5: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in rank order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Rank1 Boys' names NB Rank1 Girls' names NB babies babies 1 Jack 486 * 1 Olivia 512 * 2 Oliver 380 * 2 Emily 460 3 James 368 * 3 Isla 395 4 Lewis 356 4 Sophie 370 5 Logan 324 5 Amelia 321 6 Noah 318 6 Jessica 318 * 7 Harris 299 7 Ava 294 8 Alexander 297 * 8 Ella 290 * 9 Leo 289 * 9 Charlotte 280 * 10 Harry 282 * 10 Aria 254 * 11 Alfie 275 11 Lucy 248 12 Finlay 262 * 12 Lily 244 13 Jacob 258 * 13 Grace 240 14 Charlie 257 14 Freya 235 15 Aaron 236 * 15 Ellie 228 16 Lucas 235 * 16= Evie 216 17 Rory 234 16= Sophia 216 * 18 Mason 231 * 18 Harper 203 * 19= Archie 229 * 19 Hannah 199 19= Thomas 229 * 20 Millie 192 21 Daniel 218 * 21 Eilidh 178 22 Adam 208 22 Chloe 174 23 Cameron 205 * 23 Mia 170 24 Max 203 24 Emma 167 25 Finn 199 25 Eva 157 26 Ethan 197 * 26 Anna 154 * 27 Matthew 190 27 Orla 150 * 28 Theo 187 * 28 Ruby 146 29 Nathan 178 29 Poppy 144 * 30 Oscar 177 30 Maisie 142 * 31 Joshua 173 31 Holly 140 32 Brodie 170 * 32 Layla 137 33 William 164 * 33 Sienna 136 34 Callum 160 34 Erin 135 35 Harrison 156 * 35 Isabella 133 36 Muhammad 145 * 36 Zara 127 37 Caleb 139 37 Georgia 126 38= Jude 135 38= Amber 120 * 38= Samuel 135 38= Skye 120 40= Jamie 134 40= Katie 119 40= Ollie 134 40= Rosie 119 42 Liam 132 42 Daisy 116 * 43= Jaxon 127 * 43= Alice 113 43= Luke 127 43= Sofia 113 45= Freddie 126 45 Willow 111 * 45= Isaac 126 * 46 Esme 104 47= Angus 125 47 Maya 101 -

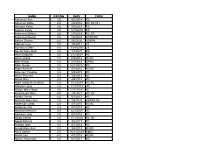

Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019

Vital Statistics Baby2019 BabyGirl GirlsNames Names | Registered in 2019 From:Jan 01, 2019 To: Dec 31, 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Aadhini 1 Aarnavi 1 Aadhirai 1 Aaro 1 Aadhya 2 Aarohi 2 Aadila 1 Aarora 1 Aadison 1 Aarushi 1 Aadroop 1 Aarya 3 Aadya 3 Aarza 2 Aafiya 1 Aashvee 1 Aaghnya 1 Aasiya 1 Aahana 2 Aasiyah 2 Aaila 1 Aasmi 1 Aaira 3 Aasmine 1 Aaleena 1 Aatmja 1 Aalia 1 Aatri 1 Aaliah 1 Aayah 2 Aalis 1 Aayara 1 Aaliya 1 Aayat 1 Aaliyah 17 Aayla 1 Aaliyah-Lynn 1 Aayna 1 Aalya 1 Aayra 2 Aamina 1 Aazeen 1 Aamna 1 Abagail 1 Aanaya 1 Abbey 4 Aaniya 1 Abbi 1 Aaniyah 1 Abbie 1 Aanya 3 Abbiejean 1 Aara 1 Abbigail 3 Aaradhya 1 Abbiteal 1 Aaradya 1 Abby 10 Aaraya 1 Abbygail 1 Aaria 2 Abdirashid 1 Aariya 1 Abeeha 1 Aariyah 1 Aberlene 1 Aarna 3 Abhideep 1 Abi 1 Abiah 1 10 Jun 2020 1 Abiegail 02:22:21 PM1 Abigael 1 Abigail 141 Abigale 1 1 10 Jun 2020 2 02:22:21 PM Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Abigayle 1 Addalyn 4 Abihail 1 Addalynn 1 Abilene 2 Addasyn 1 Abina 1 Addelyn 1 Abisha 2 Addi 1 Ablakat 1 Addie 2 Aboni 1 Addilyn 3 Abrahana 1 Addilynn 2 Abreen 1 Addison 61 Abrielle 2 Addisyn 2 Absalat 1 Addley 1 Abuk 2 Addy 1 Abyan 1 Addyson 2 Abygale 1 Adedoyin 1 Acadia 1 Adeeva 1 Acelynn 1 Adeifeoluwa 1 Achai 1 Adela 1 Achan 1 Adélaïde 1 Achol 1 Adelaide 20 Ackley 1 Adelaine 1 Ada 23 Adelayne 1 Adabpreet 1 Adele 4 Adaeze 1 Adèle 2 Adah 1 Adeleigha 1 Adair 1 Adeleine 1 Adalee 1 Adelheid 1 Adalena 1 Adelia 3 Adaley 1 Adelina 2 Adalina 2 Adeline 40 Adalind 1 Adella -

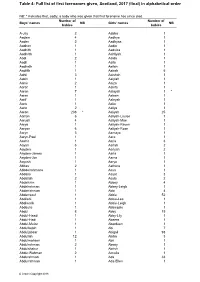

Table 4: Full List of First Forenames Given, Scotland, 2016 (Final) In

Table 4: Full list of first forenames given, Scotland, 2017 (final) in alphabetical order NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died. Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB babies babies A-Jay 2 Aabha 1 Aadam 4 Aadhya 1 Aaden 2 Aadhyaa 1 Aadhan 1 Aadia 1 Aadhith 1 Aadvika 1 Aadhrith 1 Aahliyah 1 Aadi 2 Aaida 1 Aadil 1 Aaila 1 Aadirath 1 Aailah 1 Aadrith 1 Aairah 5 Aahil 3 Aaishah 1 Aakin 1 Aaiylah 1 Aamir 2 Aaiza 1 Aaraf 1 Aakifa 1 Aaran 7 Aalayah 1 * Aarav 1 Aaleen 1 Aarif 1 Aaleyah 1 Aariv 1 Aalia 1 Aariz 2 Aaliya 1 Aaron 236 * Aaliyah 25 Aarron 6 Aaliyah-Louise 1 Aarush 4 Aaliyah-Mae 1 Aarya 1 Aaliyah-Raven 1 Aaryan 6 Aaliyah-Rose 1 Aaryn 3 Aamaya 1 Aaryn-Paul 1 Aara 1 Aashir 1 Aaria 3 Aayan 6 Aariah 2 Aayden 1 Aariyah 2 Aayden-James 1 Aarla 1 Aayden-Jon 1 Aarna 1 Aayush 1 Aarya 1 Abbas 2 Aathera 1 Abbdelrahmane 1 Aava 1 Abdalla 1 Aayat 3 Abdallah 2 Aayla 2 Abdelkrim 1 Abbey 4 Abdelrahman 1 Abbey-Leigh 1 Abderrahman 1 Abbi 4 Abderraouf 1 Abbie 52 Abdilahi 1 Abbie-Lee 1 Abdimalik 1 Abbie-Leigh 1 Abdoulie 1 Abbiegale 1 Abdul 8 Abby 19 Abdul-Haadi 1 Abby-Lily 1 Abdul-Hadi 1 Abeera 1 Abdul-Muizz 1 Aberdeen 1 Abdulfattah 1 Abi 7 Abduljabaar 1 Abigail 93 Abdullah 12 Abiha 3 Abdulmohsen 1 Abii 1 Abdulrahman 2 Abony 1 Abdulshakur 1 Abrish 1 Abdur-Rahman 2 Accalia 1 Abdurahman 1 Ada 33 Abdurrahman 1 Ada-Ellen 1 © Crown Copyright 2018 Table 4 (continued) NB: * indicates that, sadly, a baby who was given that first forename has since died Number of Number of Boys' names NB Girls' names NB -

Board of Commissioners Meeting Tuesday, June 28, 2016

City of Henderson, Kentucky Board of Commissioners Meeting Tuesday, June 28, 2016 Municipal Center Third Floor Assembly Room 222 First Street 5:30 P.M. AGENDA 1. Invocation: Reverend Mary Wrye, Methodist Hospital Chaplain 2. Roll Call: 3. Recognition of Visitors: 4. Appearance of Citizens: 5. Proclamations: "World Changers Week" 6. Presentations: 7. Public Hearings: 8. Consent Agenda: Minutes: June 14, 2016 Regular Meeting Resolutions: a. Resolution Authorizing Submittal of Grant Application to the Kentucky Office of Homeland Security (KOHS) for Funds in the Amount of $280,000.00 to Purchase New 911 Phone System, and Acceptance of Grant if Awarded b. Resolution Adopting and Approving Execution of Municipal Road Aid Cooperative Program Agreement for FY 2017 c. Resolution Approving Agreement with the Henderson City County Airport Board Allocating $135,336.00 for Airport Services d. Resolution Approving Agreement with the Downtown Henderson Partnership Allocating $46,000.00 for Services in Support of Downtown Henderson Please mute or turn off all cell phones for the duration of this meeting. e. Resolution Approving Agreement with Kentucky Network for Development, Leadership and Engagement, Inc. (Kyndle) Allocating $60,000.00 for Economic Development Services f. Resolution Approving Agreement with the Humane Society of Henderson County, Inc. Allocating $9,166.67 on a Monthly Basis for Animal Control and Shelter Services g. Resolution Approving Memorandum of Understanding Between the City of Henderson and Henderson County Tourist Commission Regarding Personnel for the Henderson Welcome Center h. Resolution Approving Community Development Block Grant Subrecipient Agreement with the Father Bradley Shelter for Women and Children, Inc. i. -

English Versions of Foreign Names

ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Aaron Aron . Aaron Aron Aranne Arek Aron Aaron Aron Aron Aron Aron Aronek Aronos Abel Avel . Abel Abel Abele . Avel Abel Hebel Avel Awel Abraham Braha Abram Abraham Avram Abramo Abraham . Abram Abraham Bramek Abram Abrasha Avram Abramek Abrashen Ovrum Abrashka Avraam Avraamily Avram Avramiy Avarasha Avrashka Ovram Achilies . Achille Achill . Akhilla . Akhilles Akhilliy Akhylliy Ada . Ada Ada Ara . Ariadna Page 1 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adalbert Vojta . Wojciech . Vojtech Wojtek Vojtek Wojtus Adam Adam . Adam Adam Adamo Adam Adamik Adamka Adi Adamec Adi Adamek Adamko Adas Adamek Adrein Adas Adamok Damek Adok Adela Ada . Ada Adel . Adela Adelaida Adeliya Adelka Ela AdeliAdeliya Dela Adelaida . Ada . Adelaida . Adela Adelayida Adelaide . Adah . Etalka Adele . Adele . Adelina . Adelina . Adelbert Vojta . Vojtech Vojtek Adele . Adela . Page 2 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adelina . -

NAME RATING DATE CODE Aaronson Sue 3.5 4/3/2014 RC

NAME RATING DATE CODE Aaronson Sue 3.5 4/3/2014 RC Abraham Sallie 4.0 2/6/2016 RC RC DH Abruzzo Kathy 3.5 7/3/2014 RC Ackerle Cindy 3.0 12/3/2015 RC Ackerman Debra 3.5 2/7/2019 RC RC Ackerman Randi 3.0 2/6/2020 RCRCRC Adkins Sharon 4.0 2/6/2020 USAPA Adkison Liza 3.5 4/8/2011 72 Agnolucci Debi 3.0 7/28/2010 23 Aguilar Mary Beth 3.5 1/7/2021 RC Ahart Deborah 3.5 5/12/2021 RC Ahern Diane 5.0 6/2/2016 RCRC Aker Kandy 4.0 2/1/2018 DHRC Albin Susan 3.5 12/14/2017 RC Alden Kathryn 3.0 4/7/2016 RCRC Alderson Yanping 3.5 5/9/2019 RC Alfieri Theresa 3.0 1/4/2012 30 Allard Mary 3.0 4/5/2018 RC Allen Deborah (Debbie) 3.5 7/11/2019 RC RC Allensen Judy 3.0 11/7/2019 RC Allison Mary Moon 3.5 12/17/2011 80 Alumbaugh Mary 4.0 2/4/2021 RC RC Amato Cheryl 3.5 6/1/2017 RC Amstutz Mary Ann 3.5 3/5/2020 USAPA tbc Anderson Linda 4.0 4/7/2016 RCRC Anderson Pat 3.5 3/1/2018 RC Andrews Bernice 3.0 12/3/2015 RC Andrews Judi 3.0 4/7/2016 RC Angel Donna 3.5 11/1/2018 RC RC Apple Patricia 3.0 3/2/2017 RC Aranbo Joan 3.5 8/7/2014 RC Arcadi Mary Ann 3.0 3/5/2015 RCRC Arico Jackie 2.5 10/11/2018 SpRC Arnall Cari 4.0 4/7/2016 RCRC Arnieri Rosemary 3.0 6/1/2017 RC Asbury Cathryn 3.5 7/11/2019 RC Asher Tamara 2.5 2/1/2018 RC Ashman Sandy 4.0 3/3/2016 RC Askeland Pam 2.5 9/19/2013 87 RC RC Astrologes Darlene 3.5 11/7/2019 RC RC Atienza Mary 3.0 10/3/2013 84 RC RC Augustus Lan 3.5 2/1/2018 RCRCRCRC Azeka Joan 4.5 8/2/2018 RC Baas Susan 3.5 10/11/2018 SpRC Babe Pat 3.5 2/2/2017 RC Babich-Keating Julie 3.0 2/1/2018 RC Baczek Linda 3.0 9/6/2018 RC Bagley Carolyn 5.0 5/9/2019 -

In-Depth Characterization of Stromal Cells Within the Tumor Microenvironment Yields Novel Therapeutic Targets

cancers Review In-Depth Characterization of Stromal Cells within the Tumor Microenvironment Yields Novel Therapeutic Targets Sebastian G. Walter 1, Sebastian Scheidt 2, Robert Nißler 3 , Christopher Gaisendrees 1 , Kourosh Zarghooni 4 and Frank A. Schildberg 2,* 1 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University Hospital Cologne, 50937 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] (S.G.W.); [email protected] (C.G.) 2 Clinic for Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, University Hospital Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute of Physical Chemistry, Göttingen University, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] 4 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospital Cologne, 50931 Cologne, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: This up-to-date and in-depth review describes fibroblast-derived cells and their role within the tumor microenvironment for tumor progression. Moreover, targets for future antitu- mor therapies are summarized and potential aspects for future translational research are outlined. Furthermore, this review discusses the challenges and possible obstacles related to certain treat- ment targets. Citation: Walter, S.G.; Scheidt, S.; Abstract: Cells within the tumor stroma are essential for tumor progression. In particular, cancer- Nißler, R.; Gaisendrees, C.; associated fibroblasts (CAF) and CAF precursor cells (resident fibroblasts and mesenchymal stromal Zarghooni, K.; Schildberg, F.A. cells) are responsible for the formation of the extracellular matrix in tumor tissue. Consequently, In-Depth Characterization of Stromal CAFs directly and indirectly mediate inflammation, metastasis, immunomodulation, angiogenesis, Cells within the Tumor and the development of tumor chemoresistance, which is orchestrated by complex intercellular Microenvironment Yields Novel cytokine-mediated crosstalk. -

Le Grand Sentier D'alberta

The Great Trail in Alberta Le Grand Sentier d’Alberta This marks the connection of Alberta’s section of The Great Trail of Canada in honour of Canada’s 150th anniversary Ceci marque le raccordement du Grand Sentier à travers d’Alberta pour le 150e anniversaire de la Confédération of Confederation in 2017. canadienne en 2017. À partir d’où vous êtes, vous pouvez entreprendre l’un des voyages les plus beaux et les plus diversifiés du monde. From where you are standing, you can embark upon one of the most magnificent and diverse journeys in the world. Que vous vous dirigiez vers l’est, l’ouest, le nord ou le sud, Le Grand Sentier du Canada — créé par le sentier Whether heading east, west, north or south, The Great Trail—created by Trans Canada Trail (TCT) and its partners— Transcanadien (STC) et ses partenaires — vous offre ses multiples beautés naturelles ainsi que la riche histoire et offers all the natural beauty, rich history and enduring spirit of our land and its peoples. l’esprit qui perdure de notre pays et des gens qui l’habitent. Launched in 1992, just after Canada’s 125th anniversary of Confederation The Great Trail was conceived by a group of Lancé en 1992, juste après le 125e anniversaire de la Confédération du Canada, Le Grand Sentier a été conçu, par un visionary and patriotic individuals as a means to connect Canadians from coast to coast to coast. groupe de visionnaires et de patriotes, comme le moyen de relier les Canadiens d’un océan aux deux autres. -

Pulse and Their By-Products As Animal Feed

FAO Pulses and their by-products as animal feed Pulses and their by-products Humans have been using pulses, and legumes Pulses also play an important role in providing in general, for millennia. Pulses currently valuable products for animal feeding and thus play a crucial role in sustainable development indirectly contribute to food security. Pulse Pulses and their by-products due to their nutritional, environmental and by-products are valuable sources of protein economic values. The United Nations General and energy for animals and they do not Assembly, at its 68th session, declared 2016 compete with human food. Available as animal feed as the International Year of Pulses to further information on this subject has been collated promote the use and value of these important and synthesized in this book, to highlight the crops. Pulses are an affordable source of nutritional role of pulses and their by-products protein, so their share in the total protein as animal feed. This publication is one of consumption in some developing countries the main contributions to the legacy of the ranges between 10 and 40 percent. Pulses, International Year of Pulses. It aims to enhance like legumes in general, have the important the use of pulses and their by-products in ability of biologically fixing nitrogen and those regions where many pulse by-products some of them are able to utilize soil-bound are simply dumped and will be useful for phosphorus, thus they can be considered the extension workers, researchers, feed industry, cornerstone of sustainable agriculture. policy-makers and donors alike. Pulses and their by-products as animal feed by P.L. -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT to DONORS on the Cover: a Close-Up of Máximo’S Massive Skeletal Frame

2018 ANNUAL REPORT TO DONORS On the cover: A close-up of Máximo’s massive skeletal frame. His placement in the renovated Stanley Field Hall invites guests to get up-close and personal. Visitors can walk under the titanosaur’s massive legs and sit at his feet. 2 Griffin Dinosaur Experience 4 Native North America Hall 6 Because Earth. The Campaign for the Field Museum 8 Science 16 Engagement 24 Honor Roll Contents 2 Field Museum Dear Friends, In its historic 125th anniversary year, the Field Museum achieved a new level of accomplishment in science, public engagement, and philanthropy. We are grateful to all donors and members for championing our mission to fuel a journey of discovery across time to enable solutions for a brighter future rich in nature and culture. In September 2018, the Museum’s Board of Trustees launched the public phase of an ambitious fundraising initiative. Because Earth. The Campaign for the Field Museum will raise $250 million dollars for our scientific enterprises, exhibitions, programs, and endowment. Our dedication to Earth’s future is strengthened by a new mission and brand that reinforce our commitment to global scientific leadership. Over the past six years, the Museum has transformed more than 25 percent of its public spaces, culminating in 2018 with renovations of Stanley Field Hall and the unveiling of the Griffin Dinosaur Experience. We are deeply grateful to the Kenneth C. Griffin Charitable Fund for an extraordinary commitment to dinosaur programs at the Field. In 2018, we also announced a three-year renovation of the Native North America Hall and unveiled the Rice Native Gardens with a land dedication ceremony in October. -

Indiana University Office of Public & Media Relations

Indiana University Office of Public & Media Relations NEWS Dec. 21, 1999 RELEASES 1999 Concussion Guidelines For Athletes Not Reliable, IU Sports Medicine Specialist Says Article Listing INDIANAPOLIS -- An Indiana University School of Medicine sports medicine specialist believes that current guidelines used by many professional and amateur sports teams do not provide adequate safety standards for players. INDIANA December 21, UNIVERSITY 1999 Douglas B. McKeag, M.D., chairman of the IU Department of Family Medicine and a SCHOOL OF Concussion nationally recognized expert in sports medicine, addressed the controversial issue in MEDICINE Guidelines For a "Contempo" article appearing in the Dec. 21 issue of the Journal of the American Athletes Not Medical Association (JAMA). Contributing to the opinion piece were Michael Collins, MEDIA Reliable, IU Ph.D., and Mark Lovell, Ph.D., of the Division of Neuropsychology at Henry Ford RELATIONS Sports Health System in Detroit. Medicine Specialist "My job as a team physician is to make sure that before I return a player to a game he A STATEWIDE RESOURCE Says is fully functioning and capable of protecting himself," said Dr. McKeag. "Current guidelines focus more on a player using consciousness as a means of determining his risk, but our research shows that multiple minor incidents can be more damaging." Phone December 16, 317 274 7722 1999 Death Rate Dr. McKeag said that mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI), which can be diagnosed through a series of simple tests, is a better yardstick for determining long-term injury Fax From from sports-related head injury. MTDI does not imply loss of consciousness, but 317 278 8722 Accidents symptoms do include loss of equilibrium or disorientation.