Wilson, William 1819-1848

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Fellmeth

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Fellmeth. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania 2010 Coles Family Papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - Coles Family Papers Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Coles, Edward, 1786-1868. Title -

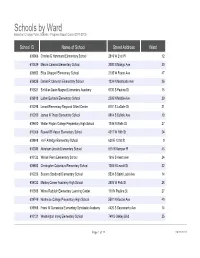

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

H. Doc. 108-222

THIRTIETH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1847, TO MARCH 3, 1849 FIRST SESSION—December 6, 1847, to August 14, 1848 SECOND SESSION—December 4, 1848, to March 3, 1849 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE M. DALLAS, of Pennsylvania PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—DAVID R. ATCHISON, 1 of Missouri SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—ASBURY DICKINS, 2 of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—ROBERT BEALE, of Virginia SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—ROBERT C. WINTHROP, 3 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN B. FRENCH, of New Hampshire; THOMAS J. CAMPBELL, 4 of Tennessee SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—NEWTON LANE, of Kentucky; NATHAN SARGENT, 5 of Vermont DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT E. HORNER, of New Jersey ALABAMA CONNECTICUT GEORGIA SENATORS SENATORS SENATORS 14 Arthur P. Bagby, 6 Tuscaloosa Jabez W. Huntington, Norwich Walter T. Colquitt, 18 Columbus Roger S. Baldwin, 15 New Haven 19 William R. King, 7 Selma Herschel V. Johnson, Milledgeville John M. Niles, Hartford Dixon H. Lewis, 8 Lowndesboro John Macpherson Berrien, 20 Savannah REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Fitzgerald, 9 Wetumpka REPRESENTATIVES James Dixon, Hartford Thomas Butler King, Frederica REPRESENTATIVES Samuel D. Hubbard, Middletown John Gayle, Mobile John A. Rockwell, Norwich Alfred Iverson, Columbus Henry W. Hilliard, Montgomery Truman Smith, Litchfield John W. Jones, Griffin Sampson W. Harris, Wetumpka Hugh A. Haralson, Lagrange Samuel W. Inge, Livingston DELAWARE John H. Lumpkin, Rome George S. Houston, Athens SENATORS Howell Cobb, Athens Williamson R. W. Cobb, Bellefonte John M. Clayton, 16 New Castle Alexander H. Stephens, Crawfordville Franklin W. Bowdon, Talladega John Wales, 17 Wilmington Robert Toombs, Washington Presley Spruance, Smyrna ILLINOIS ARKANSAS REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE John W. -

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: a Round Table

Lincoln Studies at the Bicentennial: A Round Table Lincoln Theme 2.0 Matthew Pinsker Early during the 1989 spring semester at Harvard University, members of Professor Da- vid Herbert Donald’s graduate seminar on Abraham Lincoln received diskettes that of- fered a glimpse of their future as historians. The 3.5 inch floppy disks with neatly typed labels held about a dozen word-processing files representing the whole of Don E. Feh- renbacher’s Abraham Lincoln: A Documentary Portrait through His Speeches and Writings (1964). Donald had asked his secretary, Laura Nakatsuka, to enter this well-known col- lection of Lincoln writings into a computer and make copies for his students. He also showed off a database containing thousands of digital note cards that he and his research assistants had developed in preparation for his forthcoming biography of Lincoln.1 There were certainly bigger revolutions that year. The Berlin Wall fell. A motley coalition of Afghan tribes, international jihadists, and Central Intelligence Agency (cia) operatives drove the Soviets out of Afghanistan. Virginia voters chose the nation’s first elected black governor, and within a few more months, the Harvard Law Review selected a popular student named Barack Obama as its first African American president. Yet Donald’s ven- ture into digital history marked a notable shift. The nearly seventy-year-old Mississippi native was about to become the first major Lincoln biographer to add full-text searching and database management to his research arsenal. More than fifty years earlier, the revisionist historian James G. Randall had posed a question that helps explain why one of his favorite graduate students would later show such a surprising interest in digital technology as an aging Harvard professor. -

A Letter from Jefferson to Edward Coles

Educational materials were developed through the Making Master Teachers in Howard County Program, a partnership between Howard County Public School System and the Center for History Education at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Teacher Page: Resource Sheet #09 Source: Letter From Thomas Jefferson to Edward Coles. Monticello: August 25, 1814, Jefferson’s Farm Book. Note: Edward Coles was born into a wealthy slave-owning family in Albemarle County, Virginia. Coles studied at the College of William & Mary and was convinced that slavery was wrong. He sought for many years to find a way to free the slaves he inherited from his father; one of the wealthiest men in what was then the western frontier of Virginia. He became the second governor of Illinois, serving from 1822 to 1826. He was influential in opposing a movement to make Illinois a slave state in its early years. He often corresponded with Jefferson at Monticello. Document Analysis: 1. How does Jefferson feel about slaves and African-Americans when considering their capabilities as citizens? Jefferson equates African-Americans to children, unable to take care of themselves and destined to become a burden to society as free persons. 2. How does Jefferson react to the possibility that, if slavery is abolished, inter-racial offspring (amalgamation) may occur? It would be a horrible condition, one that which “no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character can innocently consent.” 3. What does Jefferson believe that slaves will do, if they are not used actively as laborers? Non-working slaves could create a problem for the society at large. -

The Democratic Split During Buchanan's Administration

THE DEMOCRATIC SPLIT DURING BUCHANAN'S ADMINISTRATION By REINHARD H. LUTHIN Columbia University E VER since his election to the presidency of the United States Don the Republican ticket in 1860 there has been speculation as to whether Abraham Lincoln could have won if the Democratic party had not been split in that year.' It is of historical relevance to summarize the factors that led to this division. Much of the Democratic dissension centered in the controversy between President James Buchanan, a Pennsylvanian, and United States Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. The feud was of long standing. During the 1850's those closest to Buchanan, par- ticularly Senator John Slidell of Louisiana, were personally antagonistic toward Douglas. At the Democratic national conven- tion of 1856 Buchanan had defeated Douglas for the presidential nomination. The Illinois senator supported Buchanan against the Republicans. With Buchanan's elevation to the presidency differences between the two arose over the formation of the cabinet.2 Douglas went to Washington expecting to secure from the President-elect cabinet appointments for his western friends William A. Richardson of Illinois and Samuel Treat of Missouri. But this hope was blocked by Senator Slidell and Senator Jesse D. Bright of Indiana, staunch supporters of Buchanan. Crestfallen, 'Edward Channing, A History of the United States (New York, 1925), vol. vi, p. 250; John D. Hicks, The Federal Union (Boston and New York, 1937), p. 604. 2 Much scholarly work has been done on Buchanan, Douglas, and the Democratic rupture. See Philip G. Auchampaugh, "The Buchanan-Douglas Feud," and Richard R. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Former Governors of Illinois

FORMER GOVERNORS OF ILLINOIS Shadrach Bond (D-R*) — 1818-1822 Illinois’ first Governor was born in Maryland and moved to the North - west Territory in 1794 in present-day Monroe County. Bond helped organize the Illinois Territory in 1809, represented Illinois in Congress and was elected Governor without opposition in 1818. He was an advo- cate for a canal connecting Lake Michigan and the Illinois River, as well as for state education. A year after Bond became Gov ernor, the state capital moved from Kaskaskia to Vandalia. The first Illinois Constitution prohibited a Governor from serving two terms, so Bond did not seek reelection. Bond County was named in his honor. He is buried in Chester. (1773- 1832) Edward Coles (D-R*) — 1822-1826 The second Illinois Governor was born in Virginia and attended William and Mary College. Coles inherited a large plantation with slaves but did not support slavery so he moved to a free state. He served as private secretary under President Madison for six years, during which he worked with Thomas Jefferson to promote the eman- cipation of slaves. He settled in Edwardsville in 1818, where he helped free the slaves in the area. As Governor, Coles advocated the Illinois- Michigan Canal, prohibition of slavery and reorganization of the state’s judiciary. Coles County was named in his honor. He is buried in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1786-1868) Ninian Edwards (D-R*) — 1826-1830 Before becoming Governor, Edwards was appointed the first Governor of the Illinois Territory by President Madison, serving from 1809 to 1818. Born in Maryland, he attended college in Pennsylvania, where he studied law, and then served in a variety of judgeships in Kentucky. -

The Illinois State Capitol

COM 18.10 .qxp_Layout 1 8/1/18 3:05 PM Page 2 Celebrations State Library Building renamed the Illinois State Library, Gwendolyn Brooks Building Brooks Gwendolyn Library, State Illinois the renamed Building Library State House and Senate Chambers receive major renovation major receive Chambers Senate and House Arsenal Building burns; replaced in 1937 by the Armory the by 1937 in replaced burns; Building Arsenal State Capitol participates in Bicentennial Bicentennial in participates Capitol State Capitol renovations completed renovations Capitol Archives Building renamed the Margaret Cross Norton Building Norton Cross Margaret the renamed Building Archives Illinois State Library building opened building Library State Illinois Centennial Building renamed the Michael J. Howlett Building Howlett J. Michael the renamed Building Centennial Attorney General’s Building dedicated Building General’s Attorney Capitol Building centennial and end of 20 years of renovation of years 20 of end and centennial Building Capitol Archives Building completed Building Archives Stratton Building completed Building Stratton Illinois State Museum dedicated Museum State Illinois Centennial Building completed Building Centennial Capitol Building groundbreaking Building Capitol Legislature meets in new Capitol Building Capitol new in meets Legislature Capitol Building construction completed construction Building Capitol Supreme Court Building dedicated Building Court Supreme Legislature authorizes sixth Capitol Building Capitol sixth authorizes Legislature 2018 2012 2006 1867 1868 1877 1888 1908 1923 1934 1938 1955 1963 1972 1988 1990 1992 1995 2003 Capitol Complex Timeline: Complex Capitol e u s o i n H e K t a a t s S k t a s s r i k F i ; a a d ; n C u t a o p R i l t o o t i l p a B C u n i i l l d a i e n s g e t i a n t s V s a s a n l g d d a e l n i i a a ; t S O : t l d h g i S r t o a t t t f e e L SECOND ST. -

The Impeachment and Removal of Governor Rod Blagojevich

A JUST CAUSE The Impeachment and Removal of Governor Rod Blagojevich Bernard H. Sieracki Foreword by Jim Edgar Southern Illinois University Press Carbondale Contents Foreword ix Jim Edgar Prologue 1 1. The Crisis Erupts 6 2. Cause for Impeachment 19 3. The House Investigation 33 4. The Impeachment Resolution 85 5. Senate Preparations 105 6. The Trial 113 7. The Last Day 160 Epilogue 190 Notes 195 Index 209 Gallery starting on page 95 Prologue n Tuesday, December 9, 2008, a gray dawn arrived over Illinois, bringing an intermittent rain and a chill in the air. It was one of Othose damp, early winter days when the struggle between fall and winter seems finally resolved, and people go on with a sense of acceptance. There was nothing special about the dawning of this day, but that would rapidly change. In the early morning hours an FBI arrest team arrived at the Chicago home of Governor Rod Blagojevich and took him quickly into custody. The arrest was conducted like a raid. The governor was not given advance warning or the courtesy of being able to turn himself in; rather, he was snatched in the night like a common criminal. Wearing a jogging suit and handcuffs, the stunned governor was photographed being led away by federal agents. Word of the governor’s arrest quickly spread throughout the state and began a political crisis that would grip Illinois for the next seven weeks and three days. 1 Prologue With helicopters hovering overhead, broadcasting events on live televi- sion, news crews followed the caravan of police and federal vehicles trans- porting the governor through the streets of Chicago, first to a federal lockup facility on the city’s near west side and then downtown to federal court. -

Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: an Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University

BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University Compiled by STANLEY B. KIMBALL 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 The Library SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Carbondale—Edwardsville Bibliographic Contributions No. 1 SOURCES OF MORMON HISTORY IN ILLINOIS, 1839-48 An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 Compiled by Stanley B. Kimball Central Publications Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois ©2014 Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, May, 1966 FOREWORD In the course of developing a book and manuscript collection and in providing reference service to students and faculty, a univeristy library frequently prepares special bibliographies, some of which may prove to be of more than local interest. The Bibliographic Contributions series, of which this is the first number, has been created as a means of sharing the results of such biblio graphic efforts with our colleagues in other universities. The contribu tions to this series will appear at irregular intervals, will vary widely in subject matter and in comprehensiveness, and will not necessarily follow a uniform bibliographic format. Because many of the contributions will be by-products of more extensive research or will be of a tentative nature, the series is presented in this format. Comments, additions, and corrections will be welcomed by the compilers. The author of the initial contribution in the series is Associate Professor of History of Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, Illinois. He has been engaged in research on the Nauvoo period of the Mormon Church since he came to the university in 1959 and has published numerous articles on this subject. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions.