Fredie Floré & Javier Gimeno Martínez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Nominees 2019"

• EUROPEAN UNION PRIZE FOR EUm1esaward CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE 19 MIES VAN DER ROHE Name Work country Work city Offices Pustec Square Albania Pustec Metro_POLIS, G&K Skanderbeg Square Albania Tirana 51N4E, Plant en Houtgoed, Anri Sala, iRI “New Baazar in Tirana“ Restoration and Revitalization Albania Tirana Atelier 4 arTurbina Albania Tirana Atelier 4 “Lalez, individual Villa” Albania Durres AGMA studio Himara Waterfront Albania Himarë Bureau Bas Smets, SON-group “The House of Leaves". National Museum of Secret Surveillance Albania Tirana Studio Terragni Architetti, Elisabetta Terragni, xycomm, Daniele Ledda “Aticco” palace Albania Tirana Studio Raça Arkitektura “Between Olive Trees” Villa Albania Tirana AVatelier Vlora Waterfront Promenade Albania Vlorë Xaveer De Geyter Architects The Courtyard House Albania Shkodra Filippo Taidelli Architetto "Tirana Olympic Park" Albania Tirana DEAstudio BTV Headquarter Vorarlberg and Office Building Austria Dornbirn Rainer Köberl, Atelier Arch. DI Rainer Köberl Austrian Embassy Bangkok Austria Vienna HOLODECK architects MED Campus Graz Austria Graz Riegler Riewe Architekten ZT-Ges.m.b.H. Higher Vocational Schools for Tourism and Catering - Am Wilden Kaiser Austria St. Johann in Tirol wiesflecker architekten zt gmbh Farm Building Josef Weiss Austria Dornbirn Julia Kick Architektin House of Music Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck Erich Strolz, Dietrich | Untertrifaller Architekten Exhibition Hall 09 - 12 Austria Dornbirn Marte.Marte Architekten P2 | Urban Hybrid | City Library Innsbruck Austria Innsbruck -

Brussels, a Journey at the Heart of Art Nouveau Horta/Hankar/Van De Velde Summerschool / 8–19 June 2020

Brussels, a Journey at the Heart of Art Nouveau Horta/Hankar/Van de Velde Façade Maison Autrique, Victor Horta © Marie-Françoise Plissart Horta © Marie-Françoise Victor Autrique, Maison Façade Summerschool / 8–19 June 2020 Brussels, a Journey at the Heart of Art Nouveau Horta/Hankar/Van de Velde Summerschool 8–19 June 2020 Victor Horta, Henry van de Velde and Paul Hankar are pioneers of Art Nouveau in Brussels and Europe. Brussels’ streets have dramatically changed under their influence and became the setting where their talent blossomed. The Faculty of Architecture La Cambre Horta at Université libre de Bruxelles invites you to dive into the heritage of these Architecture giants through academic lectures and exclusive site visits led by internationally renowned experts. From the beginnings of Art Nouveau to its peak, from the private mansion to the public school, from furniture to ornamentation, from destruction to preservation, you will undertake a journey at the heart of Art Nouveau and discover Brussels through a unique lens. Escalier Maison Autrique, Victor Horta © Marie-Françoise Plissart Horta © Marie-Françoise Victor Autrique, Maison Escalier Programme* The programme includes several exclusive 1. The beginnings of Art Nouveau visits in Brussels led by renowned experts. 2. The renewal of ornament (1861–1920): See our website for more details The examples of Victor Horta and Paul Hankar Target audience 3. Art Nouveau in Brussels and across Students and young professionals with a Europe background or profound interest in archi- 4. Victor Horta the Royal Museums of tecture, arts, history and urban renovation. Art and History: Reconstitution of the Magasins Wolfers and The Pavilion of Learning outcomes Human Passions Participants will be able to make the link 5. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

FEATS Programme 1978

4; ANTWERP SPONSOR FEATS ‘78 FESTIVAL OF EUROPEAN ANGLOPHONE THEATRICAL SOCIETIES ,PROVINCIAAL CENTRUM ARENBERGSCHOUWBURG, ANTWERP MAY 26- 26, 1978 FEATS ‘78 organized in co-operation with the City of Antwerp georganizeerd in samenwerking met de Stad Antwerpen under the patronage of / onder de bescberming tan A. Kinsbergen, Gouverneur van de Provincie Antwerpen Sir David Muirhead, K.C.M.G., C.V.O., Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to Belgium M. Groesser - Schroyens, Burgemeester van de Sled Antwerpen L. Van den Driessche, Rector van de Universitaire Instelling Antwerpen Theo Peters, Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul-General John P. Heimann, Consul-General of the United States of America Dom De Gruyter, Directeur van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Schouwburg, Antwerpen Alfons Goris, Directeur van Studio Herman Teirlinck, Antwerpen Walter Claessens, Directeur van het Reizend Volkstheater, Provincie Antwerpen E. Traey, Directeur Koni nkl ijk Muziekconservatorium Antwerpen R.J. Lhonneux, Voorzitter van de Kamer van Koophandel en Nijverheid, Antwerpen E.L Bridges, Chairman of the British Coordinating Committee Antwerp and wIth special thanks to / en met bljzonder. dank san The British Council, for financial support Phillips Petroleum Company, for donating the FEATS ‘78 cup Schweppes Ltd, for their support Les Fonderies de Cobegge a Andenne, for their assistance FEATS ‘78 organized in co-operation with the City of Antwerp georganizeerd in samenwerking met de Stad Antwerpen under the patronage of / onder de bescberming tan A. Kinsbergen, Gouverneur van de Provincie Antwerpen Sir David Muirhead, K.C.M.G., C.V.O., Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to Belgium M. Groesser - Schroyens, Burgemeester van de Sled Antwerpen L. -

Brussels, the Avant-Garde, and Internationalism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography <new page>Chapter 15 Met opmaak ‘Streetscape of New Districts Permeated by the Fresh Scent of Cement’:. Brussels, the Avant-Garde, and Internationalism1 La Jeune Belgique (1881–97);, L’Art Moderne (1881–1914);, La Société Nouvelle (1884–97);, Van Nu en Straks (1893–94; 1896– 1901); L’Art Libre (1919–22);, Signaux (1921, early title of Le Disque Vert, 1922–54);, 7 Arts (1922–8);, and Variétés (1928– 30). Francis Mus and Hans Vandevoorde In 1871 Victor Hugo was forced to leave Brussels because he had supported the Communards who had fled there.2 This date could also be seen as symbolisiizing the 1 This chapter has been translated from the Dutch by d’onderkast vof. 2 Marc Quaghebeur, ‘Un pôle littéraire de référence internationale’, in Robert Hoozee (ed.), Bruxelles. Carrefour de cultures (Antwerp: Fonds Mercator, 2000), 95–108. For a brief 553 passing of the baton from the Romantic tradition to modernism, which slowly emerged in the 1870s and went on to reach two high points: Art Nouveau at the end of the nineteenth century and the so-called historical avant-garde movements shortly after World War I. The significance of Brussels as the capital of Art Nouveau is widely acknowledged.3 Its renown stems primarily from its architectural achievements and the exhibitions of the artist collective ‘Les XX’ (1884–93),4 which included James Ensor, Henry Van de Velde, Théo van Rysselberghe, George Minne, and Fernand Khnopff. -

092-095-Belgium-Brussels 1893.Cdr

SHORT Marie Resseler ARTICLESB russels 1893, Belgium the Origins of an ART NOUVEAU Aesthetic Revolution. The year 1893 sees the official birth of Art apartment buildings. These houses are Nouveau in Brussels with the construction of characterized by a plan consisting of three two emblematic houses: the Hôtel Tassel built successive rooms and a stairwell placed along by Victor Horta and the private house of the the common wall. This plan restricts light and architect Paul Hankar. They are both located circulation and hinders creativity. The Art near the prestigious tree-lined avenue Louise Nouveau architects fought against this stan- in a trendy new area of the capital which has dardised architecture that didn't really evolve been known since then as the cradle of Art but was simply repeated over and over again. Nouveau. This new quarter attracts the wealthy Two young men were an exception among the bourgeoisie, who build their mansions in the future inhabitants of this new quarter near eclectic style which then dominated Brussels. avenue Louise: Emile Tassel, an engineer and The city is unique in being a capital where friend of Victor Horta, and the architect Paul people live in single-family houses instead of Hankar. wwww Eclecticism in Brussels: the Palace of Justice (architect Joseph Poelaert, 1863-1886) © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, negative E23517 92 Uncommon Culture Octave van Rysselberghe is a pioneer, a visionary architect who in 1882, more than ten years before the birth of Art Nouveau, had already built a house that was a break with the traditional styles, the Hôtel Goblet d'Alviella. -

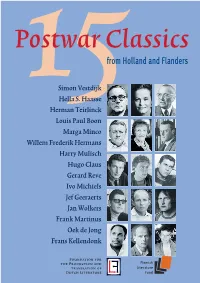

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

Iin Search of a European Style

In Search of a I European Style Our European Community built upon an economic base Art Nouveau was a movement started by the new is being increasingly defined as a shared socio-cultural space. middle-classes, who established themselves in cities such as Within this new spirit, art and architecture are, like music, Glasgow, Brussels, Nancy, Berlin and Barcelona, where it laid universal languages and have become an indisputable the roots for this emerging social class. There is nothing reference point for overcoming social, religious or linguistic better, therefore, than a network of cities to explain this differences in the various countries. Furthermore, a simple movement. The Art Nouveau European Route-Ruta Europea analysis of the evolution of art throughout history shows that del Modernisme is a project whose aim is the cultural styles have always spread across the continent at an amazing dissemination and promotion of the values of Art Nouveau speed. Artistic styles have defined specifically European heritage, offering a tour through the different cities models such as the Romanesque, Gothic or Renaissance, etc. comprising this network, where one can enjoy the These spread across Europe but always left a trace of each ornamental wealth of the movement and the beauty of its nation's indigenous values. This process has been appreciated forms. All of these cities sought a common project of since the appearance of the first Medieval styles and was also modernity in the diversity of their Art Nouveau styles. The evident in Art Nouveau, probably the most cosmopolitan and narrative thread of this book can be found in a collection of international of European styles. -

SCHRIJVERS DIE NOG MAAR NAMEN LIJKEN Het Onvoorstelbare Thema Van Herman Teirlinck

SCHRIJVERS DIE NOG MAAR NAMEN LIJKEN Het onvoorstelbare thema van Herman Teirlinck In de reeks Schrijvers die nog maar namen lijken buigen jonge auteurs, literatuurcritici en -wetenschappers zich over twintigste-eeuwse schrijvers van wie de naam wel breed bekend is, maar van wie men zich kan afvragen of ze nog wel worden gelezen. Bart Van der Straeten vertelt hoe hij Herman Teirlinck op het spoor kwam en leest een oeuvre dat op verschillende manieren één groot onderliggend thema lijkt uit te beelden. Het is de verhulling van de waarheid die ons met elkaar verbindt en die wij in elkaar herkennen. Een foto van Herman Teirlinck in brasserie De Drie Fonteinen in Beersel _ BART VAN DER STRAETEN Herman Teirlinck was een naam die wel eens opdook, nu en dan, in verschillende con- texten, maar waar ik nooit een helder beeld van kreeg. Op televisie hoorde ik in mijn jeugd verhalen over de Studio Herman Teirlinck, de roemruchte acteursopleiding in Antwerpen die zowat elk Vlaams acteertalent had gevormd. De Studio was door Teir- linck zelf opgericht in 1946 en bleef bestaan tot ongeveer 2000; Teirlinck had er zelf lesgegeven, onder meer aan de latere directrice van de studio Dora van der Groen. De documentaire Herman Teirlinck van de filmmaker Henri Storck uit 1953 toont beelden van Teirlinck als een autoritair en bevlogen lesgever, die met onder anderen acteur-in- opleiding Senne Rouffaer van gedachten wisselt over de interpretatie van het Middelne- derlandse toneelstuk Elckerlijc. Teirlincks opvattingen over theater zijn in 1959 gebun- deld in Dramatisch peripatetikon, eind 2017 opnieuw uitgegeven door ASP Editions. -

Bauhaus Engl 01 13 LA Innen Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 1

01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 1 Boris Friedewald Bauhaus Prestel Munich · London · New York 01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 2 01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 3 p. 9 Context “A ceremony of our own” p. 21 Fame Battles and Bestsellers p. 33 School The Laboratory of Modernism p. 83 Life Freedom, Celebration, and Arrests p. 105 Love Workshop of Emotions p. 117 Today The Bauhaus Myth 01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 4 Context 01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 5 “The main principle of the Bauhaus is the idea of a new unity; a gathering of art, styles, and appearances that forms an indivisible unit. A unit that is complete within its self and that generates its meaning only through animated life.” Walter Gropius, 1925 01_15_LA_RB_bauhaus_engl_01_13_LA_Innen_Dali Schwarz 12.02.16 12:11 Seite 6 Modernism’s Lines of Development The Bauhaus was unique, avant-garde, and pursued a path that led purpose- fully toward Modernism. Its members practiced an anti-academic education, had a concept of utopia and sought the mankind of the future, for whom they wanted to design according to need. Before the Bauhaus there had admittedly already been various reformist approaches to, and ideas on, education and art. But the Bauhaus was unique because it concentrated these aspirations and made them into reality. The Expressionist Bauhaus Many pieces of work by the students, but also by the masters, from the first years of the Bauhaus speak an Expressionist language and continue an artistic direction that came into being before the First World War. -

Flemish Community)

Youth Wiki national description Youth policies in Belgium (Flemish Community) 2019 The Youth Wiki is Europe's online encyclopaedia in the area of national youth policies. The platform is a comprehensive database of national structures, policies and actions supporting young people. For the updated version of this national description, please visit https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/youthwiki 1 Youth 2 Youth policies in Belgium (Flemish Community) – 2019 Youth Wiki Belgium (Flemish Community) ........................................................................... 6 1. Youth Policy Governance................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Target population of youth policy ............................................................................................. 8 1.2 National youth law .................................................................................................................... 8 1.3 National youth strategy ........................................................................................................... 10 1.4 Youth policy decision-making .................................................................................................. 14 1.5 Cross-sectoral approach with other ministries ....................................................................... 18 1.6 Evidence-based youth policy ................................................................................................... 18 1.7 Funding youth policy -

Henry Van De Velde's Use of the Concept of Art Nouveau in His Early

Erik Buelinckx Henry van de Velde’s use of the concept Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, Brussels of art nouveau in his early writings Introduction s’est inclinée vers la terre; que la fleur flétrie que les siècles piétinent dans leur marche disparaîtra à son tour dans la nuit I would like to express my gratitude to the organisers of this quand le total anéantissement intellectuel du vieux continent interesting conference on a very important period of European sera accompli. Ils pressentent que l’Art Nouveau se bégayera art and history. I also wish to thank Partage Plus, the European par un peuple innocent et ravi qui suivra d’amour et de soins project which made it possible for me to relaunch my inter- les diverses phases de sa transformation, s’extasiant à chacune est in art nouveau, especially in Belgium, and to facilitate my d’elles, persuadé qu’aucune de plus splendide ne sera possible participation to this conference.1 At last, a very special and et que l’Art, une fois de plus, se transplantera vers l’ouest, à la warm thank you to my lovely colleague, Marie Resseler, for suite des hommes, pour refleurir dans les Amériques».3 helping me in making our institute’s contribution to Partage The anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus once pointed out Plus a success for as well the project as for the advancement of in a letter to his friend van de Velde that in the East they think our scientifically described photographic inventory of cultural civilisation came from the West and in the West they think it heritage in Belgium.