Mvc Rtp 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martha's Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan 2020–2040

Martha’s Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan 2020–2040 July 2019 Prepared by the Martha’s Vineyard Commission and the Martha’s Vineyard Joint Transportation Committee in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, and Massachusetts Department of Transportation Martha’s Vineyard MPO / Joint Transportation Committee c/o The Martha’s Vineyard Commission P.O. Box 1447 Oak Bluffs, MA 02557 Phone: 508-693-3453 Fax: 508-693-7894 The preparation of the Martha’s Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) was financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Please note: All maps are included in this RTP for illustrative purposes only, and are available in higher quality from the MVC staff if requested. Cover (clockwise from top right): A Steamship Authority ferry docking in Vineyard Haven, taxis staging at the Vineyard Haven Terminal, bicyclists along Ocean Drive in Oak Bluffs, solar canopies at Cronig’s Market in West Tisbury. Martha’s Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan 2020–2040 July 2019 CONTENTS Participants and Endorsement 1 Executive Summary 3 Transportation Planning Organizations 5 Section 1: Transportation Systems at a Glance 6 Woods Hole, Martha’s -

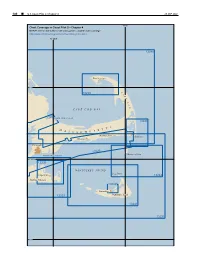

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Part Iii. Nantucket and the World's People

PART III. NANTUCKET AND THE WORLD’S PEOPLE Foreword Nantucket’s English settler families were not the first inhabitants of the island, nor has there ever been a time when their progeny, the “descended Nantucketers,” were the only residents. Sarah P. Bunker, who serves as the leitmotif for these Nantucketers, lived in a house built hard by a Wampanoag burial site and inherited a basket made for her father by Abram Quary, Nantucket’s “last Indian.” When she was a girl, her father—a sea captain in the China trade—was in the habit of receiving crewmen and foreigners at home, and he employed live-in “help” to assist with the care and upkeep of what was grandly known as “the Pinkham estate.” Years later, in the straitened circumstances of her widowhood, Sarah P. supported the household by nursing injured, sick, and dying people of “all sorts” as Nantucket’s bone-setter Zaccheus Macy had done a century earlier.1 As she lived out the last decade of her life in her upstairs room, what reached her ears from downstairs day in, day out was the incomprehensible conversation of her grand- daughter-in-law’s relatives from Finland. Sarah P. knew full well that on Nantucket there were strangers to be found wherever one turned, not just in sailors boarding houses and the servants quarters of descended Nantucketers’ houses. Parts I and II have followed the history of the Wampanoags who were in possession of the island before the English came; the Africans who were brought here by the English; and many people who came from other islands in the employ of Nantucketers. -

Ex B. Architect's Proposal

EXHIBIT B (CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS ARCHITEaS PROPOSAL TO STAMFORD RFP 681) Proposalpreparedfot THE CITY Oi STAMFORD Architectural/Engineering Services Relocation of the Hoyt-Barnum House RFP No. 681 i- JULY 30, 2015 ARCHITECTS LLC TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. COVER LETTER 2. TECHNICAL RESPONSE - FIRM OVERVIEWS - LISTING OF SIMILAR PROJECTS - TEAM ORGANIZATIONAL CHART - PAST PERFORMANCE RECORD 3. REFERENCES 4. PROPOSAL SUMMARY - PROJECT MANAGEMENT PLAN - TEAM RESUMES -RELEVANT EXPERIENCE 5. FEE PROPOSAL cm CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS ARCHITECTS LLC July 30.2015 Mr.Jeffrey Pardo, Construction Manager Cityof Stamford 888 Washington Boulevard Stamford, CT06904 RE: RFP No.681, Relocation of The Hoyt-Barnum House Dear Mr. Pardo and Members ofthe Selection Committee, Therelocation of the Hoyt-Barnum houseisa challenging projectwe are veryinterested in,excited about,and,alongwithourconsultantteam,wellqualified for. CWA hasbeenthe architectfortwo moved buildings inthe pasttwelveyears-a 13,000 SF brick building (formerly a mansion) forYale University and a 2,000SF housefor the City of NewHaven. Theseprojects, alongwith particularly relevantothers, are described Inmoredetail elsewhereinthis proposal. Mostof our practice consistsof variouscombinations and levels of renovation, rehabilitation and adaptive re-useof existingbuildings, whichsometimesinclude additions. Engaged Inover300 projects for Yale University overthe pasttwenty years,we are currently renovating theirMarsh Hall, a building listed onthe National Historic Register of Historic Places. Wehave wonseveral -

From 1940 to 2011

A Cumulative Index for and From 1940 to 2011 © 2010 Steamship Historical Society of America 2 This is a publication of THE STEAMSHIP HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA, INC. 1029 Waterman Avenue, East Providence, RI 02914 This project has been compiled, designed and typed by Jillian Fulda, and funded by Brent and Relly Dibner Charitable Trust. 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part Subject Page I Listing of whole numbers of issues, 3 with publication date of each II Feature Articles 6 III Authors of Feature Articles 42 IV Illustrations of Vessels 62 V Portraits 150 VI Other Illustrations (including cartoons) 153 VII Maps and Charts 173 VIII Fleet Lists 176 IX Regional News and Departments 178 X Reviews of Books and Other Publications 181 XI Obituaries 214 XII SSHSA Presidents 216 XIII Editors-in-Chief 216 (Please note that Steamboat Bill becomes PowerShips starting with issue #273.) 3 PART I -- WHOLE NUMBERS AND DATES (Under volume heading will follow issue number and date of publication.) VOLUME I 33 March 1950 63 September 1957 34 June 1950 64 December 1957 1 April 1940 35 September 1950 2 August 1940 36 December 1950 VOLUME XV 3 December 1940 4 April 1941 VOLUME VIII 65 March 1958 5 August 1941 66 June 1958 6 December 1941 37 March 1951 67 September 1958 7 April 1942 38 June 1951 68 December 1958 8 August 1942 39 September 1951 9 December 1942 40 December 1951 VOLUME XVI VOLUME II VOLUME IX 69 Spring 1959 70 Summer 1959 10 June 1943 41 March 1952 71 Fall 1959 11 August 1943 42 June 1952 72 Winter 1959 12 December 1943 43 September 1952 13 April 1944 -

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021

U.S. Lighthouse Society Participating Passport Stamp Locations Last Updated: June, 2021 For complete information about a specific location see: https://uslhs.org/fun/passport-club. Visit their websites or call for current times and days of opening to insure that a stamp will be available. Some stamps are available by mail. See complete listings for locations offering this option and mail requirements. ALABAMA (3) CALIFORNIA FLORIDA HAWAII MAINE Fort Morgan Museum Table Bluff Tower Carysfort Reef McGregor Point Halfway Rock Middle Bay Trinidad Head Cedar Keys Nawiliwili Harbor Hendricks Head Sand Island Trinidad Head Memorial Crooked River Heron Neck ILLINOIS (2) Egmont Key Indian Island ALASKA (2) CONNECTICUT (20) Grosse Point Faro Blanco Isle au Haut Cape Decision Avery Point Metropolis Hope Light Fowey Rocks Kittery Hist. & Naval Museum Guard Island Black Rock Harbor Garden Key/Fort Jefferson INDIANA (2) Ladies Delight Brant Point Replica CALIFORNIA (40) Gasparilla Is. (Pt Boca Grande) Michigan City E Pier Libby Island Faulkner’s Island Alcatraz Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Old Michigan City Little River Five Mile Point Anacapa Island Hillsboro Inlet Lubec Channel Great Captain Island KENTUCKY (1) Angel Island Jupiter Inlet Machias Seal Island Green’s Ledge Louisville LSS Point Blunt Key West Maine Lighthouse Museum Lynde Point Point Knox Loggerhead LOUISIANA (6) Maine Maritime Museum Morgan Point Point Stuart Pacific Reef Lake Pontchartrain Basin Mark Island (Deer Is Thorofare) New London Harbor Ano Nuevo Pensacola Maritime Museum Marshall Point New London Ledge Battery Point Ponce De Leon Inlet New Canal Matinicus Rock Peck’s Ledge Cape Mendocino Port Boca Grande Rear Range Port Ponchartrain Monhegan Island Penfield Reef Carquinez Strait Rebecca Shoal Sabine Pass Moose Peak Saybrook BW East Brother Island Sand Key Southwest Reef (Berwick) Mount Desert Rock Sheffield Island Fort Point Sanibel Island Tchefuncte River Narraguagus Southwest Ledge Humbolt Bay Museum Sombrero Key Nash Island Stamford Harbor MAINE (71) Long Beach Harbor (Robot) St. -

Nantucket and Madaket Harbors Action Plan (“Plan”) Dated May 2009

NNaannttuucckkeett && MMaaddaakkeett HHaarrbboorrss AAccttiioonn PPllaann The Nantucket and Madaket Harbors Plan Review Committee & the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources Town of Nantucket, Massachusetts May 2009 As approved by the Secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs December 21, 2009 DECISION ON THE TOWN OF NANTUCKET’S REQUEST FOR APPROVAL OF THE NANTUCKET AND MADAKET MUNICIPAL HARBOR PLAN PURSUANT TO 301 CMR 23.00 December 21, 2009 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Ian A. Bowles, Secretary I. INTRODUCTION Today, as Secretary of the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), I am approving, the Nantucket and Madaket Harbors Action Plan (“Plan”) dated May 2009. This Decision presents a synopsis of Plan content and my determinations on how the Plan complies with the standards for approval set forth in the Municipal Harbor Planning regulations at 301 CMR 23.00 et seq. Pursuant to the review procedures contained therein, the Town of Nantucket (“Town”) submitted the Plan in June 2009. Following a review for completeness, a notice of public hearing and 30-day opportunity to comment was published in the Environmental Monitor dated June 11, 2009. Oral testimony was accepted during a public hearing held in the Town of Nantucket on June 22, 2009, and two written comment letters were received prior to the close of the public comment period on July 10, 2009. The review process led on my behalf by the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM), included consultation between staff of CZM, the Waterways Regulation Program of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and the Steamship Authority (SSA). -

2.5 Water Transportation

2.5 WATER TRANSPORTATION The primary form of public water transportation on Cape Cod is ferry service, carrying passengers between the mainland and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. A significant amount of freight is carried by water transportation as well. As a result, the region’s seaports and channels are vital in addressing the economic and transportation needs of Cape Cod. 2.5.1 CAPE COD SEAPORTS Cape Cod has 586 miles of tidal coastline, with many inlets and bays that provide marine access to the land. Seaports have been constructed along several of these bays and inlets to facilitate the transfer of people and goods from water to land transportation. Significant Cape Cod seaports are recognized in reports by the Army Corps of Engineers, the agency that maintains many of them. These and other seaports are discussed in this section. 2.5.1.1 Woods Hole Harbor Woods Hole Harbor, located in Falmouth, is a primary seaport for Cape Cod. It is split into two harbors by Juniper Point: Great Harbor and Little Harbor (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Little Harbor is located in the 550,000 square feet of water between Juniper and Nobska Points. In 1906, the Army Corps of Engineers completed a 1,600 foot-long channel from the Little Harbor to Vineyard Sound, as well as a turning basin. The Coast Guard widened and deepened both projects in the 1960s to a depth of 17 feet and a width of 200 and 400 feet respectively. Located on the western side of Little Harbor is a Coast Guard station, which is also used for recreational purposes. -

D28 Rev C ISLAND HOME Paper12-13-07

Tradition and Innovation: The Design of the Ferry Island Home Douglas M. Wolff, (M) Island Home is a new ferry operating between Woods Hole, Massachusetts and Martha’s Vineyard Island and represents a leap in capabilities in The Steamship Authority’s (SSA) fleet. This new double-ended ferry is significantly larger than other vessels in the SSA fleet, and features Americans with Disabilities Act compliance, lift decks, bow and stern thrusters, weathertight doors at both ends of the freight deck and a slide evacuation system. The design process started with a seakeeping analysis for the numerical modeling of realistic wave shapes and periods, which were recreated in a model basin. Tests were performed to predict ship motions and to confirm powering predictions. Numerical flow analysis was performed to identify hull form improvements. Studies assisted with decisions regarding styling, propulsion system, and the number of pilothouses. This paper follows the design process, construction period and sea trials. INTRODUCTION Year-round ferry service to Martha's Vineyard is provided by Martha's Vineyard Island, lying 4.5 miles south of Cape Cod, The Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship is a study in contrasts. The winter population of 12,200 swells Authority (SSA), an organization chartered, but not supported to 72,600 in the summer, when the rich and famous return to financially, by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. SSA their multi-million dollar cottages and day-trippers fill the operates a fleet of vessels on the following routes: streets and stores. Islanders place high value on their privacy · Woods Hole to Vineyard Haven, Martha's Vineyard but depend on summer tourist dollars to carry them through the · Woods Hole to Oak Bluffs, Martha's Vineyard lean months of winter. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X in Re : : Chapter 11 Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------------------x In re : : Chapter 11 Case No. MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY, et al., : f/k/a General Motors Corp., et al. : 09-50026 (REG) : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) ----------------------------------------------------------------x AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF NEW YORK ) ) ss: COUNTY OF SUFFOLK ) I, Barbara Kelley Keane, being duly sworn, depose and state: 1. I am an Assistant Director with The Garden City Group, Inc., the claims and noticing agent for the debtors and debtors-in-possession (the “Debtors”) in the above-captioned proceeding. Our business address is 105 Maxess Road, Melville, New York 11747. 2. On September 13, 2010, at the direction of Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP (“Weil”), counsel for the Debtors in the above-captioned case, I caused to be served by first class mail, postage prepaid, true and correct copies of the Notice of Hearing to Consider Approval of Debtors’ Proposed Disclosure Statement with Respect to Debtors’ Joint Chapter 11 Plan (“Notice of Disclosure Statement Hearing”), annexed hereto as Exhibit “A”, addressed to each of the individuals and entities in the service list attached hereto as Exhibit “B” (all parties listed in the Debtor’s Schedules of Assets and Liabilities, all parties who filed a Notice of Appearance, the master service list, and the creditor matrix not addressed in the following paragraphs). 3. Also on September 13, 2010, at the direction of Weil, I caused an appropriate number of true and correct copies of the Notice of Disclosure Statement Hearing to be served by hand delivery to Broadridge, Attn.: BSG Proxy Agent Services, JOB NOS. -

Argonauta Vol. XVIII, No. 2 ; April 2001

ARGONAUTA The Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society Volume XVIII Number Two April 2001 ARGONAUTA Founded 1984 by Kenneth MacKenzie ISSN No. 0843-8544 Editors William Schleihauf Maurice D. Smith Argonauta Editorial Office Marine Museum ofthe Great Lakes at Kingston 55 Ontario Street, Kingston, Ontario K7K 2Y2 e-mail [email protected] Telephone: (613) 542-2261 FAX: (613) 542-0043 ARGONAUTA is published four times a year-January, April, July and October The Canadian Nautical Research Society Executive Officers President: William R. Glover, Kingston Past President: G. Edward Reed, Ottawa 15t Vice-President: James Pritchard, Kingston 2nd Vice-President: Christon Archer, Calgary Councillor: Lewis R. Fischer, St. John's Councillor: Peter Haydon, Halifax Councillor: Gerald Jordan, Toronto Councillor: Maurice D. Smith, Kingston Secretary: Richard Gimblett, Ottawa Treasurer: Greg Hannah, Kingston Canadian Nautical Research Society Mailing Address Membership Business PO Box 511, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 4W5, Canada Annual Membership including four issues ofARGONAUTA and four issues of THE NORTHERNMARINERILE MARINDUNORD: Within Canada: Individuals, $45.00; Institutions, $70.00; Students, $35.00 International: Individuals, $55.00; Institutions, $80.00; Students, $45.00 April 2001 - ARGONAUTA - Page 1 In this Issue ~w~l · 1 Council Corner 2 Letters 3 Research Queries 5 Articles - William Glover "Nautical Nostalgia" 6 - Robin H. Wyllie "Maritime Provinces Steam Passenger Vessels" 8 - Rick James "Tug Salvage Chief' 13 - Alan Ruffman "The Nova Scotia Tree-Ring Project" 17 - Sarah Palmer "Seeing the Sea - The Maritime Dimension in History" 20 Members' and Museum News 34 The Periodical Literature 36 there is a direct relationship between getting Editorial access to that material and the degree of concern expressed byus. -

Volume III Appendices Vineyard Wind Project

Draft Construction and Operations Plan Volume III Appendices Vineyard Wind Project September 29, 2020 Submitted by Vineyard Wind LLC 700 Pleasant Street, Suite 510 New Bedford, Massachusetts 02740 Submitted to Prepared by Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Epsilon Associates, Inc. 45600 Woodland Road 3 Mill & Main Place, Suite 250 Sterling, Virginia 20166 Maynard, Massachusetts 01754 Draft Construction and Operations Plan Volume III Appendices Vineyard Wind Project Submitted to: BUREAU OF OCEAN ENERGY MANAGEMENT 45600 Woodland Rd Sterling, VA 20166 Submitted by: VINEYARD WIND LLC 700 Pleasant Street, Suite 510 New Bedford, MA 02740 Prepared by: EPSILON ASSOCIATES, INC. 3 Mill & Main Place, Suite 250 Maynard, MA 01754 In Association with: Baird & Associates JASCO Applied Sciences Biodiversity Research Institute Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP C2Wind Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. Capitol Air Space Group RPS Clarendon Hill Consulting Saratoga Associates Ecology and Environment Swanson Environmental Associates Foley Hoag Wood Thilsted Partners Ltd Geo SubSea LLC WSP Gray & Pape September 29, 2020 Appendix III-H.b Vineyard Wind Project Historic Properties Visual Impact Assessment VINEYARD WIND HISTORIC PROPERTIES VISUAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT VINEYARD WIND OFFSHORE WIND FARM PROJECT Submitted by: Vineyard Wind 700 Pleasant Street, Suite 510 New Bedford, MA 02740 Prepared by: Epsilon Associates, Inc. 3 Mill and Main Place, Suite 250 Maynard, MA 01754 Revised September 29, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Scope 1-1 1.2