Part Iii. Nantucket and the World's People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Nantucket Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: City/Town: Nantucket Vicinity: State: MA County: Nantucket Code: 019 Zip Code: 02554, 02564, 02584 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5,027 6,686 buildings sites structures objects 5,027 6,686 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 13,188 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Martha's Vineyard Statistical Profile February 2019

Martha’s Vineyard Statistical Profile February 2019 www.mvcommission.org PO Box 1447, 33 New York Ave, Oak Bluffs, MA 02557 [email protected] p-508-693-3453; f-508-693-7894 Health and Education 41 County health rankings: County, 2018 41 Health trends: County (various time ranges) 42 Number of arrests per town, 2007–2017 43 Arrest rate by town, 2016 43 Lyme disease cases: County comparison, 2000–2015 43 Lyme disease rates: County comparison, 2015 43 Opioid overdose deaths: County comparison, 2000–2016 44 Opioid overdose death rate: County comparison, 2016 44 Homelessness: County, 2015–2018 45 Martha’s Vineyard Center for Living and Serving Hands food distribution: County, 2013–2017 45 SNAP participation by town (percent of population), 2010–2016 45 Martha’s Vineyard Community Services: Services provided in 2017 46 Martha’s Vineyard Hospital inpatient discharges and emergency visits, 2010–2018 46 Martha’s Vineyard Hospital’s 2016 Community Health Assessment and Implementation Strategy (selected tables and charts) 47 Educational attainment by town, 2016 49 Adult education enrollment: Island 2009–2018 50 School enrollment by Island school, 2007–2017 50 Enrollment by gender (percent of school), 2017–2018 51 Selected populations (percent of school), 2017–2018 51 Plans of high school graduates (percent of students), 2016–2017 51 HEALTH AND EDUCATION The County Health Rankings, a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, measures vital health factors in counties across the United States. The program helps communi- ties understand what factors influence their overall quality and length of life, as outlined in the chart below. -

Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust

Ezra’s Archives | 77 Strategies of Survival: Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust Taly Matiteyahu On the eve of World War II, Lithuanian Jewry numbered approximately 220,000. In June 1941, the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began. Within days, Germany had occupied the entirety of Lithuania. By the end of 1941, only about 43,500 Lithuanian Jews (19.7 percent of the prewar population) remained alive, the majority of whom were kept in four ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, Siauliai, Svencionys). Of these 43,500 Jews, approximately 13,000 survived the war. Ultimately, it is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry died during the Holocaust, a percentage higher than in any other occupied Eastern European country.1 Stories of Lithuanian towns and the manner in which Lithuanian Jews responded to the genocide have been overlooked as the perpetrator- focused version of history examines only the consequences of the Holocaust. Through a study utilizing both historical analysis and testimonial information, I seek to reconstruct the histories of Lithuanian Jewish communities of smaller towns to further understand the survival strategies of their inhabitants. I examined a variety of sources, ranging from scholarly studies to government-issued pamphlets, written testimonies and video testimonials. My project centers on a collection of 1 Population estimates for Lithuanian Jews range from 200,000 to 250,000, percentages of those killed during Nazi occupation range from 90 percent to 95 percent, and approximations of the number of survivors range from 8,000 to 20,000. Here I use estimates provided by Dov Levin, a prominent international scholar of Eastern European Jewish history, in the Introduction to Preserving Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania. -

Your Trusted Resource

1 Jeffrey Bowen 781-201-9488 12 new construction luxury condos for [email protected] sale in Chelsea located at 87 Parker St. chelsearealestate.com for details THURSDAY, APRIL 18, 2019 FREE charlestown PATRIOT-BRIDGE Charlestown’s oldest resident keeps young with art and attitude By Seth Daniel If you want to be a grouch, get off my couch.” Irene Morey has lived 103 years Another secret to being young and seen just about everything ,she shared slyly, is that she’s really in modern history – from two only 26. World Wars to the inauguration “I was born on leap year, so of President John F. Kennedy – but that makes me only about 26 even Cyan her focus in all those long years, though people say I’m 103,” she and her secret to keeping young, is laughed. choosing one’s attitude. It’s with that spirit that the Magenta “Everything should be in mod- Navy Yard resident approaches eration,” she said last week. “If each and every day. you want to be happy, be happy. (MOREY Pg. 3) Yellow Yellow Black SPRING FLING AT THE K OF C Photos by Seth Daniel Somewhere between St. Patrick’s Day and Bunker Hill Day lies the Spring Fling – and City officials were on hand at the Knights of Columbus Father Daniel Mahoney Hall on Thursday, April 11, to celebrate spring. Sponsored by Mayor Martin Walsh’s Age Strong Department, State Rep. Dan Ryan and the Flatley Companies, the cele- bration featured lunch and plenty of music. Here, Judy Burton, Theresa Fraga and Liane Devine sing an Irish favorite. -

The Communist Party of Great Britain Since 1920 Also by David Renton

The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 Also by David Renton RED SHIRTS AND BLACK: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in Oxford in the ‘Thirties FASCISM: Theory and Practice FASCISM, ANTI-FASCISM AND BRITAIN IN THE 1940s THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A Century of Wars and Revolutions? (with Keith Flett) SOCIALISM IN LIVERPOOL: Episodes in a History of Working-Class Struggle THIS ROUGH GAME: Fascism and Anti-Fascism in European History MARX ON GLOBALISATION CLASSICAL MARXISM: Socialist Theory and the Second International The Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920 James Eaden and David Renton © James Eaden and David Renton 2002 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2002 978-0-333-94968-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. -

TRULY GLOBAL Worldscreen.Com *LIST 1218 ALT2 LIS 1006 LISTINGS 11/21/18 11:19 AM Page 2

*LIST_1218_ALT2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/21/18 11:19 AM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM DECEMBER 2018 ASIA TV FORUM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION TRULY GLOBAL WorldScreen.com *LIST_1218_ALT2_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 11/21/18 11:19 AM Page 2 2 TV LISTINGS ASIA TV FORUM EXHIBITOR DIRECTORY COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR THE COMPANIES IN BOLD CAN BE FOUND IN THIS EDITION OF TV LISTINGS. 108 Media L28 Five Star Production C28 NHC Media J10 9 Story Distribution International J30 Fixed Stars Multimedia D10 NHK Enterprises B10-18 A+E Networks G20 Flame Distribution L05 Nippon Animation B10-14 ABC Commercial L05 Fortune Star Media G26 Nippon TV B10-19 About Premium Content F10 FOX Networks Group D18 NPO Sales H36 ABS-CBN Corporation J18 FranceTV Distribution F10 NTV Broadcasting Company H27 ADK/NAS/D-Rights B10-15 Fred Media L05 Oak 3 Films E08/H08 AK Entertainment H10 Fremantle E20 Ocon Studios H32 Albatross World Sales L30 Fuji Creative Corporation B10-9 Off The Fence J23 Alfred Haber Distribution F30 GAD F10 Omens Studios E08/H08 all3media international K08 Gala Television Corporation D10 One Animation E08/H08 Alpha Group L10/N10 Gaumont H33 One Life Studios J04 Ampersand F10 Global Agency E27 One Take Media J28 Anima Istanbul N08 Globo K24 Only Distrib F10 Animasia Studio M28 Gloob Participants Lounge Parade Media Group H08-01 Animonsta Studios M28 GMA Worldwide J01 Paramount Pictures Suite 5201 Animoon J25 GO-N International F10 PGS Entertainment F10 Aniplex B27 GoldBee H34 Phoenix Satellite Television G24 Antares International -

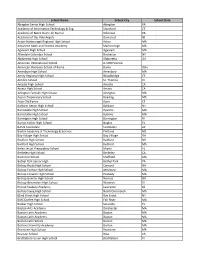

Participating School List 2018-2019

School Name School City School State Abington Senior High School Abington PA Academy of Information Technology & Eng. Stamford CT Academy of Notre Dame de Namur Villanova PA Academy of the Holy Angels Demarest NJ Acton-Boxborough Regional High School Acton MA Advanced Math and Science Academy Marlborough MA Agawam High School Agawam MA Allendale Columbia School Rochester NY Alpharetta High School Alpharetta GA American International School A-1090 Vienna American Overseas School of Rome Rome Italy Amesbury High School Amesbury MA Amity Regional High School Woodbridge CT Antilles School St. Thomas VI Arcadia High School Arcadia CA Arcata High School Arcata CA Arlington Catholic High School Arlington MA Austin Preparatory School Reading MA Avon Old Farms Avon CT Baldwin Senior High School Baldwin NY Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barrington High School Barrington RI Barron Collier High School Naples FL BASIS Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ Baxter Academy of Technology & Science Portland ME Bay Village High School Bay Village OH Bedford High School Bedford NH Bedford High School Bedford MA Belen Jesuit Preparatory School Miami FL Berkeley High School Berkeley CA Berkshire School Sheffield MA Bethel Park Senior High Bethel Park PA Bishop Brady High School Concord NH Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro MA Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody MA Bishop Guertin High School Nashua NH Bishop Hendricken High School Warwick RI Bishop Seabury Academy Lawrence KS Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth MA Blind Brook High -

Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-Quadrangle Area of Cape Cod and Islands, Southeast Massachusetts

Prepared in cooperation with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Office of the State Geologist and Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs Surficial Geologic Map of the Pocasset-Provincetown- Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-Quadrangle Area of Cape Cod and Islands, Southeast Massachusetts Compiled by Byron D. Stone and Mary L. DiGiacomo-Cohen Open-File Report 2006-1260-E U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Stone, B.D., and DiGiacomo-Cohen, M.L., comps., 2009, Surficial geologic map of the Pocasset Provincetown-Cuttyhunk-Nantucket 24-quadrangle area of Cape Cod and Islands, southeast Massachusetts: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1260-E. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Cover figure. Photograph of eroding cliffs at Gay Head on Martha’s Vineyard (source: -

Julia Anna Gardner Proceedings Volume of the Geological Society of America Annual Report for 1960 Pp

GEOL. soc. AM., PROC. FOR 1960 PLATE 6 JULIA ANNA GARDNER PROCEEDINGS VOLUME OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA ANNUAL REPORT FOR 1960 PP. 87-92. PL. 6 FEBRUARY 1962 MEMORIAL TO JULIA ANNA GARDNER (1882-1960) By HARRY S. LADD Julia Anna Gardner, distinguished paleontol worked at the Museum under contract with the ogist and authority on the stratigraphy of the U. S. Geological Survey until, at the end of Coastal Plain, died at her home in Bethesda, 1917, she joined the Red Cross for duty in Maryland, on November 15, 1960, after a long France. After the war, early in 1920, she became illness. She was 78 years of age. a Paleontologist with the Survey, a position Julia Gardner was born in Chamberlain, she was to hold for the next 32 years. South Dakota, on January 26, 1882. Her father, Miss Gardner's doctor's thesis at Johns Dr. Charles Henry Gardner, a practicing Hopkins dealt with a part of the fauna of the physician in Chamberlain, died when Julia Upper Tertiary beds of Virginia and North was but four months old. Julia was raised by Carolina, but this document was not completed her mother, Julia Brackett Gardner. Much of and published until many years later. While Julia Anna's girlhood was spent in South with the Maryland Survey she studied Upper Dakota where her early schooling was by Cretaceous mollusks and some minor groups. Her comprehensive reports in the two volumes private tutors. In 1898 mother and daughter that appeared in 1916 constituted a valuable moved to North Adams, Massachusetts, where pioneering effort. -

Modeling Population Dynamics of Roseate Terns (Sterna Dougallii) In

Ecological Modelling 368 (2018) 298–311 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Modelling j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolmodel Modeling population dynamics of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean a,b,c,∗ d e b Manuel García-Quismondo , Ian C.T. Nisbet , Carolyn Mostello , J. Michael Reed a Research Group on Natural Computing, University of Sevilla, ETS Ingeniería Informática, Av. Reina Mercedes, s/n, Sevilla 41012, Spain b Dept. of Biology, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155, USA c Darrin Fresh Water Institute, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 110 8th Street, 307 MRC, Troy, NY 12180, USA d I.C.T. Nisbet & Company, 150 Alder Lane, North Falmouth, MA 02556, USA e Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The endangered population of roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean consists Received 12 September 2017 of a network of large and small breeding colonies on islands. This type of fragmented population poses an Received in revised form 5 December 2017 exceptional opportunity to investigate dispersal, a mechanism that is fundamental in population dynam- Accepted 6 December 2017 ics and is crucial to understand the spatio-temporal and genetic structure of animal populations. Dispersal is difficult to study because it requires concurrent data compilation at multiple sites. Models of popula- Keywords: tion dynamics in birds that focus on dispersal and include a large number of breeding sites are rare in Roseate terns literature. -

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS ENERGY FACILITIES SITING BOARD ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 69J for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Facilities in Massachusetts ) for the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) EFSB 20-01 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 40A, § 3 for Exemptions from the Operation of the ) Zoning Ordinance of the Town of Barnstable for ) the Construction and Operation of New Transmission Facilities for the Delivery of Energy ) D.P.U. 20-56 from an Offshore Wind Energy Facility Located in ) Federal Waters to an NSTAR Electric (d/b/a. ) Eversource Energy) Substation Located in the ) Town of Barnstable, Massachusetts. ) ) ) Petition of Vineyard Wind LLC Pursuant to G.L. c. ) 164, § 72 for Approval to Construct, Operate, and ) Maintain Transmission Lines in Massachusetts for ) the Delivery of Energy from an Offshore Wind ) D.P.U 20-57 Energy Facility Located in Federal Waters to an ) NSTAR Electric (d/b/a Eversource Energy) ) Substation Located in the Town of Barnstable, ) Massachusetts. ) ) AFFIDAVIT OF AARON LANG I, Aaron Lang, Esq., do depose and state as follows: 1. I make this affidavit of my own personal knowledge. 2. I am an attorney at Foley Hoag LLP, counsel for Vineyard Wind LLC (“Vineyard Wind”) in this proceeding before the Energy Facilities Siting Board. 3. On September 16, 2020, the Presiding Officer issued a letter to Vineyard Wind containing translation, publication, posting, and service requirements for the Notice of Adjudication and Public Comment Hearing (“Notice”) and the Notice of Public Comment Hearing Please Read Document (“Please Read Document”) in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Mvc Rtp 2003

Martha’s Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan 2003 Update Prepared by the Martha's Vineyard Commission on behalf of the Martha's Vineyard MPO This Regional Transportation Plan was prepared by the Martha's Vineyard Commission on behalf of the Martha's Vineyard MPO, made up of: · The Massachusetts Highway Department, · The Executive Office of Transportation and Construction, · The Martha's Vineyard Commission, and · The Vineyard Transit Authority. Martha's Vineyard MPO c/o The Martha's Vineyard Commission P.O. Box 1447, Oak Bluffs, MA 02557 Telephone: 508-693-3453 Fax: 508-693-3453 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. The RTP Update Process 3. The Island and its People 4. The Regional Transportation Network 5. Water Transportation 6. Air Transportation 7. Road Network and Traffic 8. Buses and Taxis 9. Bicycles and Pedestrians 10. Freight 11. Intermodality and Information 12. Implementation 13. Conclusion Appendices A1 Commonwealth Road and Bridge Policy A2 Air Quality Conformity Documentation A3 Participants and Meetings A4 Endorsement 3 Preface The Martha's Vineyard Regional Transportation Plan is updated every three years. It outlines the Vineyard’s transportation issues and outlines proposals to deal with them. The Martha’s Vineyard Commission serves as one of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’ thirteen Regional Planning Agencies. Ten of these thirteen regional planning agencies are federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPO). The federal regulations require that an MPO be formed in urbanized areas with a population of 50,000 or more. While Martha’s Vineyard as well the Franklin County and Nantucket regions do not meet these criteria, the Executive Office of Transportation and Construction and the Massachusetts Highway Department provide planning funds for transportation planning in these regions, and essentially treat them as MPOs.