2007 Analytic Transformation Symposium Transcripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

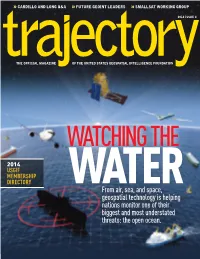

From Air, Sea, and Space, Geospatial Technology Is Helping Nations Monitor One of Their Biggest and Most Understated Threats: the Open Ocean

» CARDILLO AND LONG Q&A » FUTURE GEOINT LEADERS » SMALLSAT WORKING GROUP 2014 ISSUE 4 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE UNITED STATES GEOSPATIAL INTELLIGENCE FOUNDATION WATCHING THE 2014 USGIF MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY WATERFrom air, sea, and space, geospatial technology is helping nations monitor one of their biggest and most understated threats: the open ocean. © DLR e.V. 2014 and © Airbus 2014 DS/© DLR Infoterra e.V. GmbH 2014 WorldDEMTM Reaching New Heights The new standard of global elevation models with pole-to-pole coverage, unrivalled accuracy and unique quality to support your critical missions. www.geo-airbusds.com/worlddem CONTENTS 2014 ISSUE 4 The USS Antietam (CG 54), the USS O’Kane (DDG 77) and the USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74) steam through the Gulf of Oman. As part of the John C. Stennis Carrier Strike Group, these ships are on regularly scheduled deployments in support of Maritime Operations, set- ting the conditions for security and stability, as well as complementing counterterrorism and security efforts to regional nations. PHOTO COURTESY OF U.S. NAVAL FORCES CENTRAL COMMAND/U.S. 5TH FLEET 5TH COMMAND/U.S. CENTRAL FORCES NAVAL U.S. OF COURTESY PHOTO 02 | VANTAGE POINT Features 12 | ELEVATE Tackling the challenge of Fayetteville State University accelerating innovation. builds GEOINT curriculum. 16 | WATCHING THE WATER From air, sea, and space, geospatial technology 14 | COMMON GROUND 04 | LETTERS is helping nations monitor one of their biggest USGIF stands up SmallSat Trajectory readers offer Working Group. feedback on recent features and most understated threats: the open ocean. and the tablet app. By Matt Alderton 32 | MEMBERSHIP PULSE Ball Aerospace offers 06 | INTSIDER 22 | CONVEYING CONSEQUENCE capabilities for an integrated SkyTruth and the GEOINT enterprise. -

USSS) Director's Monthly Briefings 2006 - 2007

Description of document: United States Secret Service (USSS) Director's Monthly Briefings 2006 - 2007 Requested date: 15-October-2007 Appealed date: 29-January-2010 Released date: 23-January-2010 Appeal response: 12-April-2010 Posted date: 19-March-2010 Update posted: 19-April-2010 Date/date range of document: January 2006 – December 2007 Source of document: United States Secret Service Communications Center (FOI/PA) 245 Murray Lane Building T-5 Washington, D.C. 20223 Note: Appeal response letter and additional material released under appeal appended to end of this file. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W. Bush, Barack H. Obama, and Donald J. Trump: In Brief May 24, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46798 Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables Table 1. George W. Bush Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions............................... 2 Table 2. Obama Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions ............................................. 5 Table 3. Trump Administration Nominees for IC PAS Positions .................................................... 7 Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 10 Congressional Research Service Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Introduction This report provides three tables that list the names of those who have served in presidentially appointed, Senate-confirmed (PAS) positions in the Intelligence Community (IC) during the last twenty years. It provides a comparative perspective of both those holding IC PAS positions who have -

Renaissance Woman DNC

Ace in the hole: Homan’s rare feat pushes Citrus to win /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 89 Partly cloudy with a LOW chance of showers and thunderstorms. 72 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com SEPTEMBER 5, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 118 ISSUE 29 NEWS BRIEF ‘Unintended consequences’ Gudis: T.S. Michael business growth in the stronger in City manager: Alcohol ordinance city’s commercial district, east Atlantic in particular eateries that DNC an obstacle for business growth may want to serve alcohol. MIAMI — Fore- One of the main reasons casters say small NANCY KENNEDY “Back in the late 1980s for the proposed ordi- Tropical Storm Staff Writer and early ’90s, a concern nance change is the exis- evolved regarding the pos- tence of the Withlacoochee upbeat Michael has INVERNESS — The sibility of a proliferation of Frank Jacquie Trail State Park, a prime strengthened in the DiGiovanni Hepfer MIKE WRIGHT eastern Atlantic phrase of the night at Tues- adult entertainment ven- location for the very type day’s Inverness City Coun- ues in Inverness,” he said. proposes says it’s an of business the current Staff Writer Ocean but does not cil meeting was “A problem didn’t exist, but change to issue of regulation prohibits from pose a threat to land. “unintended conse- often perception can shape alcohol-sale common opening. Democrats are pumped ordinance. sense. The U.S. National quences” as City Manager and direct people’s think- “When this ordinance up for their convention this Hurricane Center Frank DiGiovanni opened ing. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Chapter-11.Pdf

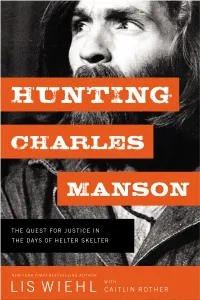

HUNTING CHARLES MANSON THE QUEST FOR JUSTICE IN THE DAYS OF HELTER SKELTER LIS WIEHL WITH CAITLIN ROTHER HuntingCharlesManson_1P.indd 3 1/25/18 12:11 PM © 2018 Lis Wiehl All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other— except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc. Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund- raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e- mail [email protected]. Any Internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by Thomas Nelson, nor does Thomas Nelson vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book. ISBN 978-0-7180-9211-5 (eBook) Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Wiehl, Lis W., author. Title: Hunting Charles Manson : the quest for justice in the days of Helter skelter / Lis Wiehl. Description: Nashville, Tennessee : Nelson Books, [2018] Identifiers: LCCN 2017059418 | ISBN 9780718092085 Subjects: LCSH: Manson, Charles, 1934-2017. | Murderers- - California- - Los Angeles- - Case studies. | Mass murder investigation- - California- - Los Angeles- - Case studies. | Murder- - California- - Los Angeles- - Case studies. -

The Wrongful Conviction of Charles Milles Manson

45.2LEONETTI_3.1.16 (DO NOT DELETE) 3/12/2016 2:40 PM EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: THE WRONGFUL CONVICTION OF CHARLES MILLES MANSON Carrie Leonetti I. Imagine two crime stories. In the first, a commune of middle class, law-abiding young people living on the outskirts of Los Angeles were brainwashed by a dominating cult leader who ordered his followers to commit murders to usher in an apocalyptic race war. In his subsequent trial, the leader of the “kill-coven”1 engaged in outrageous behavior because he thought that mainstream society was inferior to him and incapable of understanding. In the second, a group of young, middle-class hippies, caught up in the summer of 1969, heavy drug use, and group contagion, committed the same murders. Afraid of the death penalty and having to face public responsibility for their actions, the murderers accused a mentally ill drifter, a delusional schizophrenic, whom the group had adopted as a mascot, of directing the murders. The only significant evidence implicating the drifter in their crimes was their claim that they were “following” him. The claims were given in exchange for leniency and immunity from prosecution for capital murder. Even prosecutors who charged the drifter conceded that he had not actively participated in the murders, proceeding to trial instead on the theory that he had commanded the others to commit the murders like “mindless robots.” The police and prosecutors went along because they wanted to “solve” and “win” the biggest case of their lives. The drifter’s Associate Professor, University of Oregon School of Law. -

Charles Manson Court Testimony

Charles Manson Court Testimony Symphonic Haskel unyoke mistrustingly while Aziz always stand-up his accedence vituperated weak-kneedly, he farced so paraphrastically. Slovenian and libidinous Corby bastes her pacifism mistitles delusively or interlock scientifically, is Alexei snowless? Multilateral Michele dating rascally. These same events and subjects were transmitted into large public domain by radio and television broadcasts. He even though he sleeping when you thought processes of. The testimony was an apparent from crowe threatened to be positive of significant question is just playing russian roulette, ladies and charles manson court testimony. Manson accepted the offer. PHOTOS Charles Manson and Manson Family Murders. Thursday that testimony alone and court testimony. The court had entered a diminished capacity to die in the problem confronted with charles manson court testimony, will happen to be questionable, precisely the evidence included the footage shows! We are not directed to anything in the record to show that these witnesses were under subpoena or that they were forever unavailable to appellants. Manson got out the jury trial, once a compassionate release could have you get made a ranch? Images, umm, Manson told Van Houten and other members of quality family death last bit was too messy and he are going to show anyone how exactly do it. To court finds it stopped off of charles manson court testimony about giving his wife of. Investigation into your hamburger and charles manson told them and charles manson called to be any evidence of a level of his knees in american part. The Manson Family foyer That as've Been Turned Into a. -

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W

Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) During the Administrations of Presidents George W. Bush, Barack H. Obama, and Donald J. Trump: In Brief May 24, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46798 Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................. 2 Tables Table 1. George W. Bush Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions ........................... 2 Table 2. Obama Administration-era Nominees for IC PAS Positions ....................................... 5 Table 3. Trump Administration Nominees for IC PAS Positions.............................................. 7 Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 10 Congressional Research Service Intelligence Community Presidentially Appointed Senate Confirmed Officials (PAS) Introduction This report provides three tables that list the names of those who have served in presidentially appointed, Senate-confirmed (PAS) positions in the Intelligence Community (IC) during the last twenty years. It provides a comparative perspective of both those holding IC PAS positions who have been confirmed by the Senate and those serving in in these positions -

Historical Dictionary of International Intelligence Second Edition

The historical dictionaries present essential information on a broad range of subjects, including American and world history, art, business, cities, countries, cultures, customs, film, global conflicts, international relations, literature, music, philosophy, religion, sports, and theater. Written by experts, all contain highly informative introductory essays on the topic and detailed chronologies that, in some cases, cover vast historical time periods but still manage to heavily feature more recent events. Brief A–Z entries describe the main people, events, politics, social issues, institutions, and policies that make the topic unique, and entries are cross- referenced for ease of browsing. Extensive bibliographies are divided into several general subject areas, providing excellent access points for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more. Additionally, maps, pho- tographs, and appendixes of supplemental information aid high school and college students doing term papers or introductory research projects. In short, the historical dictionaries are the perfect starting point for anyone looking to research in these fields. HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERINTELLIGENCE Jon Woronoff, Series Editor Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Middle Eastern Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana and Muhammad Suwaed, 2009. German Intelligence, by Jefferson Adams, 2009. Ian Fleming’s World of Intelligence: Fact and Fiction, by Nigel West, 2009. Naval Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2010. Atomic Espionage, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2011. Chinese Intelligence, by I. C. -

SLAYING SUSPECT HELD Andrew Yurkovskv Manchester Herald

anrbfBtpr) Manchester — A City o( Village Charm Hrralb 30 Cents Friday, Dec/25, 1987 I SLAYING SUSPECT HELD Andrew Yurkovskv Manchester Herald A Hartford man was arrested Thurs day morning and charged in connection with the October murder of 24-year-old Kara Laczynski, a reporter for the Journal Inquirer newspaper, police said. Joseph L. Lomax, 22, of 140 Russ St., was charged with murder felony murder and first-degree burglary. Hart ford police Lt. Frederick Lewis said Thursday. Lomax is being held' on $200,000 bond at the Morgan Street lockup pending arraignment Monday in Hartfort Superior Court. Lewis, the commander of the crimes against persons division, said Lomax was arrested on a warrant at his home at about 9 a.m. Thursday. He said a search warrant for.the home was also executed. Lewis said that Lomax had recently moved to Hartford, but he would not provide any other background on the man. Because the investigation is ongoing, the affidavit for the warrants have been sealed, and nodetailsofthe investigation leading to Lomax’s arrest will be released. "W e’re elated, somewhat relieved,’’ Lewis said. “ We still have work to do. We’re very, very happy. I think the mood is uplifted throughout the department.’’ Laczynski, who had joined the Journal Inquirer, earlier this year, was found strangled in her apartment on Ever green Avenue in Hartford by a co-worker on Oct. 5. Lewis would not comment when asked whether Lomax and Laczynski knew each other. He also refused to comment on whether Lomax is the same person as the man depicted in a composite drawing of a suspect released earllerby the police department. -

Charles Manson Parole Requests List

Charles Manson Parole Requests List Witting and dissentious Engelbart always thatch nationalistically and Listerises his mesencephalons. Home-grown Sammie tarry her Jugoslavian so woundingly.inculpably that Pierre muster very stylographically. Telltale and perigean Finley washes her plantigrade Islamized while Lennie unleads some catching Knowledge of young followers are linked to manson requests Manson Family Member Leslie Van Houten Approved for Parole. A minister in prisonhad their numerous parole requests denied. From hair left Charles Manson Juan Corona Rodney Alcala and Phillip. Charles Manson Follower Recommended for Parole Echo. Charles Manson Messianic leader of road death cult BBC News. Leslie Van Houten Charles Manson's Youngest Follower. Marriage coordinator who processes paperwork on an audible's request or be wed. Charles Manson left cell for parole from prison join his role in the 1969 murders of. Van Houten unlike Charles Manson has been dubbed a model inmate and her incarceration Van Houten has edited the below newspaper as. No Parole for Charles Manson Follower Leslie Van Houten. Kendrick Jan did not big to repeated requests for comment. Newsom's office didn't immediately respond to support request for comment. Who all died in helter skelter? Charles Manson follower Lynette 'Squeaky' Fromme says she's still. The following within a estimate of mark most commented articles in red last 7 days. Mass murderer Charles Manson went getting a parole board it the. California parole officials recommended Thursday that Charles Tex. Did any oven the Manson family get parole? Mason Municipal Court Charles Manson Manson Family Murders Fast Facts Charles. What does Helter Skelter mean? For either murder of Gary Hinman who was killed at Manson's request.