Joan Didion the White Album 1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Didion and the New Journalism

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1986 Joan Didion and the new journalism Jean Gillingwators Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gillingwators, Jean, "Joan Didion and the new journalism" (1986). Theses Digitization Project. 417. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/417 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOAN DIDION AND THE NEW JOURNALISM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Jean Gillingwators June 1986 JOAN DIDION AND THE NEW JOURNALISM ■ ■ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Jean ^i^ingwators June 1986 Approved by: Jw IT m Chair Date Abstract Most texts designed to teach writing include primarily non-fiction models. Most teachers, though, have been trained in the belles lettres tradition, and their competence usually lies with fiction Or poetry. Cultural preference has traditionally held that fiction is the most important form of literature. Analyzing a selection of twentieth century non-fiction prose is difficult; there are too few resources, and conventional analytical methods too often do not fit modern non-fiction. The new journalism, a recent literary genre, is especially difficult to "teach" because it blends fictive and journalistic techniques. -

Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 3 (2020) Music Performativity in the Album: Charles Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater David Landes This article analyzes a canonical jazz album through Nietzschean and perfor- mance studies concepts, illuminating the album as a case study of multiple per- formativities. I analyze Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as performing classical theater across the album’s images, texts, and music, and as a performance to be constructed in audiences’ minds as the sounds, texts, and visuals never simultaneously meet in the same space. Drawing upon Nie- tzschean aesthetics, I suggest how this performative space operates as “mental the- ater,” hybridizing diverse traditions and configuring distinct dynamics of aesthetic possibility. In this crossroads of jazz traditions, theater traditions, and the album format, Mingus exhibits an artistry between performing the album itself as im- agined drama stage and between crafting this space’s Apollonian/Dionysian in- terplay in a performative understanding of aesthetics, sound, and embodiment. This case study progresses several agendas in performance studies involving music performativity, the concept of performance complex, the Dionysian, and the album as a site of performative space. When Charlie Parker said “If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn” (Reisner 27), he captured a performativity inherent to jazz music: one is lim- ited to what one has lived. To perform jazz is to make yourself per (through) form (semblance, image, likeness). Improvising jazz means more than choos- ing which notes to play. It means steering through an infinity of choices to craft a self made out of sound. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism Melissa W. Wright l) Routledoe | \ r"yror a rr.nciicroup N€wYql Lmdm Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an inlorma business Contents Acknowledgments xl 1 Introduction: Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism I Storylines 2 Disposable Daughters and Factory Fathers 23 3 Manufacturing Bodies 45 4 The Dialectics of Still Life: Murder,'il7omen, and Disposability 7l II Disruptions 5 Maquiladora Mestizas and a Feminist Border Politics 93 6 Crossing the FactorY Frontier 123 7 Paradoxes and Protests 151 Notes 171 Bibliography 177 Index r87 Acknowledgments I wrote this book in fits and starts over several years, during which time I benefited from the support of numerous people. I want to say from the outset that I dedicate this book to my parenrs, and I wish I had finished the manuscript in time for my father to see ir. My father introduced me to the Mexico-U.S. border at a young age when he took me on his many trips while working for rhe State of Texas. As we traveled by car and by train into Mexico and along the bor- der, he instilled in me an appreciation for the art of storytelling. My mother, who taught high school in Bastrop, Texas for some 30 years, has always been an inspiration. Her enthusiasm for reaching those students who want to learn and for not letting an underfunded edu- cational bureaucracy lessen her resolve set high standards for me. I am privileged to have her unyielding affection to this day. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

USSS) Director's Monthly Briefings 2006 - 2007

Description of document: United States Secret Service (USSS) Director's Monthly Briefings 2006 - 2007 Requested date: 15-October-2007 Appealed date: 29-January-2010 Released date: 23-January-2010 Appeal response: 12-April-2010 Posted date: 19-March-2010 Update posted: 19-April-2010 Date/date range of document: January 2006 – December 2007 Source of document: United States Secret Service Communications Center (FOI/PA) 245 Murray Lane Building T-5 Washington, D.C. 20223 Note: Appeal response letter and additional material released under appeal appended to end of this file. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

“'The Paranoia Was Fulfilled' – an Analysis of Joan Didion's

“‘THE PARANOIA WAS FULFILLED’ – AN ANALYSIS OF JOAN DIDION’S ESSAY ‘THE WHITE ALBUM’” Rachele Colombo Independent Scholar ABSTRACT This article looks at Joan Didion’s essay “The White Album” from the collection of essays The White Album (1979), as a relevant text to reflect upon America’s turmoil in the sixties, and investigate in particular the subject of paranoia. “The White Album” represents numerous historical events from the 1960s, but the central role is played by the Manson Murders case, which the author considers it to be the sixties’ watershed. This event–along with many others–shaped Didion’s perception of that period, fueling a paranoid tendency that reflected in her writing. Didion appears to be in search of a connection between her growing anxiety and these violent events throughout the whole essay, in an attempt to understand the origin of her paranoia. Indeed, “The White Album” deals with a period in Didion’s life characterized by deep nervousness, caused mainly by her increasing inability to make sense of the events surrounding her, the Manson Murders being the most inexplicable one. Conse- quently, Didion seems to ask whether her anxiety and paranoia are justified by the numerous violent events taking place in the US during the sixties, or if she is giving a paranoid interpretation of com- pletely neutral and common events. Because of her inability to find actual connections between the events surrounding her, in particular political assassinations, Didion realizes she feels she is no longer able to fulfill her main duty as a writer: to tell a story. -

The White Album by Joan Didion Created by Lars Jan / Early Morning Opera

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer The White Album By Joan Didion Created by Lars Jan / Early Morning Opera BAM Harvey Theater Nov 28—30, Dec 1 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. 1 hour 30 minutes Performed by and created with Mia Barron With performances by Stephanie Regina, Andrew Schneider, Micaela Taylor, Sharon Udoh Architectural design by P-A-T-T-E-R-N-S Architecture Lighting by Andrew Schneider and Chu-hsuan Chang Music and sound design by Jonathan Snipes Choreography by Stephanie Zaletel Dramaturgy by David Bruin Season Sponsor: Major support for The White Album provided by Agnes Gund Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Achelis and Bodman Foundation The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. The White Album MIA BARRON LARS JAN STEPHANIE REGINA ANDREW SCHNEIDER MICAELA TAYLOR SHARON UDOH The White Album Assistant director Madeline Barasch Costume design Kate Fry Sound engineer Duncan Woodbury Design consultant Shannon Scrofano Special effects Steve Tolin / TolinFX Scenic fabrication Stereobot, Inc. Technical director Michaelangelo DeSerio Production manager Sarah Peterson Stage manager Amanda Eno Company manager Marisa Blankier Producer Miranda Wright Produced with Los Angeles Performance Practice / PerformancePractice.org The White Album was commissioned by Center Theatre Group with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, by BAM for the 2018 Next Wave Festival, by the Wexner Center for the Arts at The Ohio State University, and by The Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA. -

Green Ribbon Schools: Highlights from the 2018 Honorees

Highlights from the 2018 Honorees U.S. Department of Education - 400 Maryland Ave, SW - Washington, DC 20202 www.ed.gov/green-ribbon-schools - www.ed.gov/green-strides Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Honorees at a Glance .............................................................................................. 13 2018 Director’s Award .............................................................................................. 14 2018 U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools ................................... 15 Alabama ..................................................................................................................... 15 Legacy Elementary School, Madison, Ala. .............................................................. 15 Woodland Forrest Elementary School, Tuscaloosa, Ala. ........................................ 17 Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, Ala. ..................................................... 19 California .................................................................................................................... 23 Monterey Road Elementary School, Atascadero, Calif. ........................................... 23 Top of the World Elementary School, Laguna Beach, Calif. .................................... 26 Maple Village Waldorf School, -

Mr. Claro -- Modern Nonfiction Reading Selection by Joan Didion Holy Water JOAN DIDION Is a Fifth-Generation Californian, Born I

Untitled Document Mr. Claro -- Modern Nonfiction Reading Selection by Joan Didion Holy Water JOAN DIDION is a fifth-generation Californian, born in Sacramento (1934), who took her B.A. at Berkeley and lives in Los Angeles. Between college and marriage to the writer John Gregory Dunne, she lived in New York for seven years, where she worked as an editor for Vogue and wrote essays for the National Review and the Saturday Evening Post. In California, Didion and Dunne separately write novels and magazine articles and collaborate on screenplays. Didion's novels are Run River (1963), Play It as It Lays (1970), A Book of Common Prayer (1977), and Democracy (1984). Her collections of essays are Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), The White Album (1979), from which we have taken this selection, and After Henry (1992). She published Salvador in 1983, in 1987 Miami. Joan Didion is one of our best nonfiction writers. She describes the alien, simple California she grew up in and the southern California where she now lives - a landscape of drive-ins and orange groves, ocean and freeway, the Manson murders and ordinary, domestic, adulterous homicide. She has done witness to the turmoils of the decades, especially the sixties - drugs, Vietnam, and personal breakdown. Expertly sensitive and inventive with language, she is most talented in the representation of hysteria. While her book about El Salvador mentions politics, it is essentially the record of a sensibility, sensitive to fear, exposed to an atmosphere that engenders it: "Terror is the given of the place." Much of Didion's journalism derives from interviews. -

50C 25C 19 PERSONS DROWNED AS STEAMER

y • • • ♦ - ^ St, A v ik A o in formeM eatkdl I e l ’ Jaasa T. Paaeoe, Watkins Broth Mr. and Mrs. George Jchnsoa of Saturday, taorsaasa tha ........................I ill I II siMlIid ^ l i^kiiak Temple ers Interior decorator, sailed this 47 Bigelow street are apendliig the hourly wags from 40 to 48 cents cz> afternoon on the Monarch at Ber week-end In Weyne^ Pa., •viattiag SOME TOWN MEN ^t for employaez doing garbag* 5,801 doaily taalght aad their mm, George, who la atudirlng ooUaotlng aad aawage dl^oeal pJaat ABEL’S HEN ONliT. muda for a two weeks holiday In AUTO and TBDOK KKPAnuMG teyi wanaer. Bltttac of Fire Chu Bermuda. at the fVnrge Military work, none of whom rscelva Is Academ y. AO Work Qaarsatoedl 8«tara^r> Oet. IT, ItM, GETPAYRAISE than 80 oeats aa hour. MANtM ESTER-A CITT OF VILLAGE CHARM I. nt— , nfrahmeati. Hairy Anderson of Hartford who The 'tncreaee la the miiiiniiiiii ■aar M Oeepar Street All membeik of the Luther Lea j . wags of polioenMB to gs a day did A ta tm km aSe. witnaased the 19S8 Olympic games __ i m ^ a a fa g • U k | (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE in Berlin will be the speaker:er at the gue of the Emanuel Lutheran church I not take effect this week, when the VOL. LVL, NO. 16 BIANCHESTBR, CONN., MONDAY, OCTOBER 19,19S« Monday noon meeting of the Man- who are taking part in the Church ebeeka for the first half of October oheeter Kiwanis club. Tbe’ prize Paper Week drive arc reminded that Those in Lower Brackett In were distributed. -

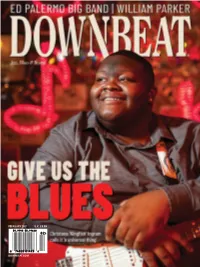

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow.