Beyond Dichotomies: Representing and Rewriting Prisoner Functionaries in Holocaust Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Ribbon Schools: Highlights from the 2018 Honorees

Highlights from the 2018 Honorees U.S. Department of Education - 400 Maryland Ave, SW - Washington, DC 20202 www.ed.gov/green-ribbon-schools - www.ed.gov/green-strides Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Honorees at a Glance .............................................................................................. 13 2018 Director’s Award .............................................................................................. 14 2018 U.S. Department of Education Green Ribbon Schools ................................... 15 Alabama ..................................................................................................................... 15 Legacy Elementary School, Madison, Ala. .............................................................. 15 Woodland Forrest Elementary School, Tuscaloosa, Ala. ........................................ 17 Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, Ala. ..................................................... 19 California .................................................................................................................... 23 Monterey Road Elementary School, Atascadero, Calif. ........................................... 23 Top of the World Elementary School, Laguna Beach, Calif. .................................... 26 Maple Village Waldorf School, -

50C 25C 19 PERSONS DROWNED AS STEAMER

y • • • ♦ - ^ St, A v ik A o in formeM eatkdl I e l ’ Jaasa T. Paaeoe, Watkins Broth Mr. and Mrs. George Jchnsoa of Saturday, taorsaasa tha ........................I ill I II siMlIid ^ l i^kiiak Temple ers Interior decorator, sailed this 47 Bigelow street are apendliig the hourly wags from 40 to 48 cents cz> afternoon on the Monarch at Ber week-end In Weyne^ Pa., •viattiag SOME TOWN MEN ^t for employaez doing garbag* 5,801 doaily taalght aad their mm, George, who la atudirlng ooUaotlng aad aawage dl^oeal pJaat ABEL’S HEN ONliT. muda for a two weeks holiday In AUTO and TBDOK KKPAnuMG teyi wanaer. Bltttac of Fire Chu Bermuda. at the fVnrge Military work, none of whom rscelva Is Academ y. AO Work Qaarsatoedl 8«tara^r> Oet. IT, ItM, GETPAYRAISE than 80 oeats aa hour. MANtM ESTER-A CITT OF VILLAGE CHARM I. nt— , nfrahmeati. Hairy Anderson of Hartford who The 'tncreaee la the miiiiniiiiii ■aar M Oeepar Street All membeik of the Luther Lea j . wags of polioenMB to gs a day did A ta tm km aSe. witnaased the 19S8 Olympic games __ i m ^ a a fa g • U k | (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE in Berlin will be the speaker:er at the gue of the Emanuel Lutheran church I not take effect this week, when the VOL. LVL, NO. 16 BIANCHESTBR, CONN., MONDAY, OCTOBER 19,19S« Monday noon meeting of the Man- who are taking part in the Church ebeeka for the first half of October oheeter Kiwanis club. Tbe’ prize Paper Week drive arc reminded that Those in Lower Brackett In were distributed. -

England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Irving V

[Home ] [ Databases ] [ World Law ] [Multidatabase Search ] [ Help ] [ Feedback ] England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> England and Wales High Court (Queen's Bench Division) Decisions >> Irving v. Penguin Books Limited, Deborah E. Lipstat [2000] EWHC QB 115 (11th April, 2000) URL: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2000/115.html Cite as: [2000] EWHC QB 115 [New search ] [ Help ] Irving v. Penguin Books Limited, Deborah E. Lipstat [2000] EWHC QB 115 (11th April, 2000) 1996 -I- 1113 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Before: The Hon. Mr. Justice Gray B E T W E E N: DAVID JOHN CADWELL IRVING Claimant -and- PENGUIN BOOKS LIMITED 1st Defendant DEBORAH E. LIPSTADT 2nd Defendant MR. DAVID IRVING (appered in person). MR. RICHARD RAMPTON QC (instructed by Messrs Davenport Lyons and Mishcon de Reya) appeared on behalf of the first and second Defendants. MISS HEATHER ROGERS (instructed by Messrs Davenport Lyons) appeared on behalf of the first Defendant, Penguin Books Limited. MR ANTHONY JULIUS (instructed by Messrs Mishcon de Reya) appeared on behalf of the second Defendant, Deborah Lipstadt. I direct pursuant to CPR Part 39 P.D. 6.1. that no official shorthand note shall be taken of this judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. Mr. Justice Gray 11 April 2000 Index Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION 1.1 A summary of the main issues 1.4 The parties II. THE WORDS COMPLAINED OF AND THEIR MEANING 2.1 The passages complained of 2.6 The issue of identification 2.9 The issue of interpretation or meaning III. -

Britannica's Holocaust Resources

Britannica’s Holocaust Resources Britannica has opened up a large portion of its database on the Holocaust: more than 100 articles, essays, and lesson / classroom prompts, some of which also contains photographs and videos. Many of the articles have been written by Dr. Michael Berenbaum, an internationally known scholar with a stellar reputation in Holocaust studies and the former director of the Research Institute at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. In essence, Britannica is offering a free encyclopedia of the Holocaust as part of a new partnership with a number of eductional institutions. More about this project can be found HERE . These Britannica articles provide an unmatched resource, and not just for teachers and students. It will certainly be of interest to anyone who would like a convenient, reliable resource for Holocaust-related information. Part 1: Hitler and the Origins of the Holocaust • ADOLF HITLER • ANTI - SEMITISM • KLAUS BARBIE • BEER HALL PUTSCH • E V A B R A U N • ADOLF EICHMANN • GENOCIDE • GESTAPO • H A N S F R A N K • HERMANN GÖRING • JULIUS STREICHER • REINHARD HEYDRICH • RUDOLF HESS • HEINRICH HIMMLER • KRISTALLNACHT • M E I N K A M P • N A Z I P A R T Y • NÜRNBERG LAWS • FRANZ VON PAPEN • ALFRED ROSENBERG • SA • SS • SWASTIKA • T HYSSEN FAMILY DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Part 2: The Holocaust • THE HOLOCAUST • NON - JEWISH VICTIMS OF TH E HOLOCAUST • A N N E F R A N K • THE DIARY OF ANNE FR ANK • MORDECAI ANIELEWICZ • ALFRIED KRUPP VON BO HLEN UND HALBACH • AUSCHWITZ • B A B Y Y A R • BELZEC • BERGEN - BELSEN • BUCHENWALD -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

Hall Johnson's Choral and Dramatic Works

Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wittmer, Micah. 2016. Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26718725 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) A dissertation presented by Micah Wittmer To The Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Music Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January, 2016 © 2016, Micah Wittmer All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Carol J. Oja Micah Wittmer -- Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) Abstract This dissertation explores the portrayal of Negro folk culture in concert performances of the Hall Johnson Choir and in Hall Johnson’s popular music drama, Run, Little Chillun. I contribute to existing scholarship on Negro spirituals by tracing the performances of these songs by the original Fisk Jubilee singers in 1867 to the Hall Johnson Choir’s performances in the 1920s-1930s, with a specific focus on the portrayal of Negro folk culture. -

Documenting Nazi Atrocities - Early Films on the Liberation of the Camps Fri 8 May – Fri 12 June 2015

Press Release DOCUMENTING NAZI ATROCITIES - EARLY FILMS ON THE LIBERATION OF THE CAMPS FRI 8 MAY – FRI 12 JUNE 2015 Henri Cartier-Bresson. Le Retour (The Return), France 1945/46 To commemorate 70 years since the end of the Second World War, the Goethe-Institut London is showing a series of films documenting the liberation of the Nazi camps. Straight after the war, the Allied programme of ‘re-education’ aimed to confront the German population with its responsibility for the rise of National Socialism and its extermination policies. Moving images played an important role in this process. The Goethe-Institut is running four film programmes with contributions from the four Allied Powers. The films were made between 1944 and 1946. Rarely seen and some translated into English for the first time, they bear witness to the atrocities committed against Jews, Roma and Sinti and other groups declared as ‘undesirable’ by the Nazis. Two additional programmes include later works by filmmakers such as Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Harun Farocki and Emil Weiss, who take a more personal view and stand out for their new approaches to representing the camps. The series is accompanied by discussions with historians and film experts on those early productions and how they were reworked as archive footage, also bringing this history up to date by reflecting on how we depict violence and atrocities today. Curated by film historian Thomas Tode. In collaboration with IWM London (Imperial War Museums), the University of Essex, Queen Mary, University of London, and the Institut français du Royaume-Uni. VENUE AND TICKETS Goethe-Institut London, 50 Princes Gate, Exhibition Rd, London SW7 2PH Box Office: 020 7596 4000; Tickets: £3, free for Goethe-Institut language students and library members; booking essential For the programme ‘The French Contribution’ only: Ciné lumière, 17 Queensberry Place, London SW7 2DT Box Office: 020 7871 3515; Tickets: £10 full price, £8 conc. -

Belsen, Dachau, 1945: Newspapers and the First Draft of History

Belsen, Dachau, 1945: Newspapers and the First Draft of History by Sarah Coates BA (Hons.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University March 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the opportunities Deakin University has provided me over the past eight years; not least the opportunity to undertake my Ph.D. Travel grants were especially integral to my research and assistance through a scholarship was also greatly appreciated. The Deakin University administrative staff and specifically the Higher Degree by Research staff provided essential support during my candidacy. I also wish to acknowledge the Library staff, especially Marion Churkovich and Lorraine Driscoll and the interlibrary loans department, and sincerely thank Dr Murray Noonan for copy-editing this thesis. The collections accessed as part of an International Justice Research fellowship undertaken in 2014 at the Thomas J Dodd Centre made a positive contribution to my archival research. I would like to thank Lisa Laplante, interim director of the Dodd Research Center, for overseeing my stay at the University of Connecticut and Graham Stinnett, Curator of Human Rights Collections, for help in accessing the Dodd Papers. I also would like to acknowledge the staff at the Bergen-Belsen Gedenkstätte and Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial who assisted me during research visits. My heartfelt gratitude is offered to those who helped me in various ways during overseas travel. Rick Gretsch welcomed me on my first day in New York and put a first-time traveller at ease. Patty Foley’s hospitality and warmth made my stay in Connecticut so very memorable. -

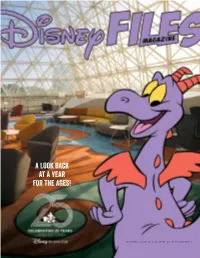

A Look Back at a Year for the Ages!

A LOOK BACK AT A YEAR FOR THE AGES! winter 2016 • Volume 25 • Number 4 I recently met some seasoned travelers who treat Walt Disney World Resorts as second homes, returning year after year and passing down their vacation traditions from generation to generation. They receive world-class service from dedicated Cast Members despite no cash changing hands at the end of their stay, and while they’re here, they make a lot of babies. Wait, you thought I was talking about Members? Sorry, I should’ve clarified. I’m talking about birds – purple martins, to be specific. Each year, these agile aerial acrobats fly more than 3,000 miles from the Brazilian Amazon to Walt Disney World Resort, where they settle into specially created accommodations perched on pedestals before finding mates and…well…you know the rest. You can learn more about these curious creatures through the latest installment of our “Quiz Ed” feature on pages 7-8. I mention the birds here because, like many stories in the pages ahead, theirs is as much about where they’re going as where they’ve been. Our community hasn’t just celebrated the past 25 years in 2016; we’ve celebrated 25 years and beyond. So where does Membership Magic go in that great “beyond?” For starters, it sees some of the most popular elements of our 25th anniversary celebration continue in the New Year (pages 3-4), it sees Members sail the Rhine in distinctive fashion (pages 5-6) and it sees one of the most beloved resorts in our neighborhood blaze new trails through the wilderness (page 9). -

Durchstarten

17. MAI 2021 | B 7230 C www.blickpunktfilm.de Nachrichten, Analysen & Trends aus der Filmwirtschaft #20 Bereit für den Neustart Fensterfragen Wir gehen damit um »The Mopes« Die Zukunft des Kinos nach Ein neuer Zusammenschluss Tanja Ziegler und Susa Kusche Wie Ipek und Christian Zübert Covid-19 steht im Fokus von sucht Verhandlungen auf über ihren aktuellen Kinodreh eine bittersüße Serie aus dem Kino 2021 Digital Augenhöhe zu den Fristen unter Corona-Bedingungen Thema Depressionen machten BALD IM KINO ix © 2021 AFTER WE FELL, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. DURCHSTARTEN SashaFilmproduktion Bühler über die beideutsche Netfl EDITORIAL Neustart Kino echs lange Monate gilt nun brauchen Auswertungsbedingungen, die schon der Total-Lockdown sich wirtschaftlich rechnen lassen. Nicht für die Kinobranche. Für zuletzt der Druck auf Verleihseite, den Mai zeichnen sich wieder Lockdown aus eigener Kraft zu überste- S erste Öff nungsperspektiven hen, hat dazu geführt, dass eine Handvoll ab. Was es jetzt braucht, ist Titel ihren Weg direkt auf die Streaming- Fairness, von Politik und Partnern. Weil plattformen genommen haben. Und mit die verspätete Impfk ampagne endlich diesen Plattformen werden sich die Kinos Fahrt aufnimmt, und die Inzidenzwer- beim Neustart arrangieren müssen. Denn te gemächlich sinken, darf wohl als letz- die großen Studios haben über sie direk- te Maßnahme auch an den Neustart der ten Zugang zu einem fi lm- und serienbe- Kultur gedacht werden. Nachdem alle geisterten Publikum bekommen, das zu Länder um uns herum bei deutlich hö- einem Teil schon vor der Pandemie nicht heren Werten den Kinos schon vor Wo- mehr den Weg in die Kinos gefunden hat. chen ein planbares Öff nungsszenario für Die Kinoketten in den USA haben sich mit Mitte Mai in Aussicht gestellt haben, den- den Studios schon auf die neuen Bedin- ken nun auch bei uns erste Bundesländer gungen verständigt: kürzere exklusive ULRICH HÖCHERL laut darüber nach, den Kinos eine Überle- Auswertungsfenster gegen bessere Kon- Herausgeber und Chefredakteur benschance einzuräumen. -

The Making of the Man's Man: Stardom and the Cultural Politics of Neoliberalism in Hindutva India

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2021 THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA Soumik Pal Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Pal, Soumik, "THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA" (2021). Dissertations. 1916. https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations/1916 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA by Soumik Pal B.A., Ramakrishna Mission Residential College, Narendrapur, 2005 M.A., Jadavpur University, 2007 PGDM (Communications), Mudra Institute of Communications, Ahmedabad, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree College of Mass Communication and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2021 DISSERTATION APPROVAL THE MAKING OF THE MAN’S MAN: STARDOM AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN HINDUTVA INDIA by Soumik Pal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Mass Communication and Media Arts Approved by: Dr. Jyotsna Kapur, Chair Dr. Walter Metz Dr. Deborah Tudor Dr. Novotny Lawrence Dr. -

1144 05/16 Issue One Thousand One Hundred Forty-Four Thursday, May Sixteen, Mmxix

#1144 05/16 issue one thousand one hundred forty-four thursday, may sixteen, mmxix “9-1-1: LONE STAR” Series / FOX TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX TELEVISION 10201 W. Pico Blvd, Bldg. 1, Los Angeles, CA 90064 [email protected] PHONE: 310-969-5511 FAX: 310-969-4886 STATUS: Summer 2019 PRODUCER: Ryan Murphy - Brad Falchuk - Tim Minear CAST: Rob Lowe RYAN MURPHY PRODUCTIONS 10201 W. Pico Blvd., Bldg. 12, The Loft, Los Angeles, CA 90035 310-369-3970 Follows a sophisticated New York cop (Lowe) who, along with his son, re-locates to Austin, and must try to balance saving those who are at their most vulnerable with solving the problems in his own life. “355” Feature Film 05-09-19 ê GENRE FILMS 10201 West Pico Boulevard Building 49, Los Angeles, CA 90035 PHONE: 310-369-2842 STATUS: July 8 LOCATION: Paris - London - Morocco PRODUCER: Kelly Carmichael WRITER: Theresa Rebeck DIRECTOR: Simon Kinberg LP: Richard Hewitt PM: Jennifer Wynne DP: Roger Deakins CAST: Jessica Chastain - Penelope Cruz - Lupita Nyong’o - Fan Bingbing - Sebastian Stan - Edgar Ramirez FRECKLE FILMS 205 West 57th St., New York, NY 10019 646-830-3365 [email protected] FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT 150 W. 22nd Street, Suite 1025, New York, NY 10011 917-484-8900 [email protected] GOLDEN TITLE 29 Austin Road, 11/F, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China UNIVERSAL PICTURES 100 Universal City Plaza Universal City, CA 91608 818-777-1000 A large-scale espionage film about international agents in a grounded, edgy action thriller. The film involves these top agents from organizations around the world uniting to stop a global organization from acquiring a weapon that could plunge an already unstable world into total chaos.