Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Do You Make Yourself a Body Without Organs?

6. November 28, 1947: How Do You Make Yourself a Body without Organs? The Dogon Egg and the Distribution of Intensities At any rate, you have one (or several). It’s not so much that it preexists or comes ready-made, although in certain respects it is preexistent. At any rate, you make one, you can’t desire without making one. And it awaits you; it is an inevitable exercise or experimentation, already accomplished the moment you undertake it, unaccomplished as long as you don’t. This is not reassuring, because you can botch it. Or it can be terrifying, and lead you to your death. It is nondesire as well as desire. It is not at all a notion or a 149 150 HOW DO YOU MAKE YOURSELF A BODY WITHOUT ORGANS? HOW DO YOU MAKE YOURSELF A BODY WITHOUT ORGANS? 151 concept but a practice, a set of practices. You never reach the Body without lungs, swallowing with your mouth, talking with your tongue, thinking with Organs, you can’t reach it, you are forever attaining it, it is a limit. People your brain, having an anus and larynx, head and legs? Why not walk on your ask, So what is this Bw0?-But you’re already on it, scurrying like a vermin, head, sing with your sinuses, see through your skin, breathe with your belly: groping like a blind person, or running like a lunatic: desert traveler and the simple Thing, the Entity, the full Body, the stationary Voyage, Anorexia, nomad of the steppes. On it we sleep, live our waking lives, fight-fight and cutaneous Vision, Yoga, Krishna, Love, Experimentation. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism Melissa W. Wright l) Routledoe | \ r"yror a rr.nciicroup N€wYql Lmdm Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an inlorma business Contents Acknowledgments xl 1 Introduction: Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism I Storylines 2 Disposable Daughters and Factory Fathers 23 3 Manufacturing Bodies 45 4 The Dialectics of Still Life: Murder,'il7omen, and Disposability 7l II Disruptions 5 Maquiladora Mestizas and a Feminist Border Politics 93 6 Crossing the FactorY Frontier 123 7 Paradoxes and Protests 151 Notes 171 Bibliography 177 Index r87 Acknowledgments I wrote this book in fits and starts over several years, during which time I benefited from the support of numerous people. I want to say from the outset that I dedicate this book to my parenrs, and I wish I had finished the manuscript in time for my father to see ir. My father introduced me to the Mexico-U.S. border at a young age when he took me on his many trips while working for rhe State of Texas. As we traveled by car and by train into Mexico and along the bor- der, he instilled in me an appreciation for the art of storytelling. My mother, who taught high school in Bastrop, Texas for some 30 years, has always been an inspiration. Her enthusiasm for reaching those students who want to learn and for not letting an underfunded edu- cational bureaucracy lessen her resolve set high standards for me. I am privileged to have her unyielding affection to this day. -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Modeling Musical Influence Through Data

Modeling Musical Influence Through Data The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811527 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Modeling Musical Influence Through Data Abstract Musical influence is a topic of interest and debate among critics, historians, and general listeners alike, yet to date there has been limited work done to tackle the subject in a quantitative way. In this thesis, we address the problem of modeling musical influence using a dataset of 143,625 audio files and a ground truth expert-curated network graph of artist-to-artist influence consisting of 16,704 artists scraped from AllMusic.com. We explore two audio content-based approaches to modeling influence: first, we take a topic modeling approach, specifically using the Document Influence Model (DIM) to infer artist-level influence on the evolution of musical topics. We find the artist influence measure derived from this model to correlate with the ground truth graph of artist influence. Second, we propose an approach for classifying artist-to-artist influence using siamese convolutional neural networks trained on mel-spectrogram representations of song audio. We find that this approach is promising, achieving an accuracy of 0.7 on a validation set, and we propose an algorithm using our trained siamese network model to rank influences. -

KRAKAUER-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf (10.23Mb)

Copyright by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Samuel Krakauer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Charles Capwell Kaushik Ghosh Kathryn Hansen Robin Moore Sonia Seeman Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer, B.A.Music; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the Bāul-Fakir musicians who were so kind, hospitable, and encouraging to me during my time in West Bengal. Without their friendship and generosity this work would not have been possible. জয় 巁쇁! Acknowledgements I am grateful to many friends, family members, and colleagues for their support, encouragement, and valuable input. Thanks to my parents, Henry and Sarah Krakauer for proofreading my chapter drafts, and for encouraging me to pursue my academic and artistic interests; to Laura Ogburn for her help and suggestions on innumerable proposals, abstracts, and drafts, and for cheering me up during difficult times; to Mark and Ilana Krakauer for being such supportive siblings; to Stephen Slawek for his valuable input and advice throughout my time at UT; to Kathryn Hansen -

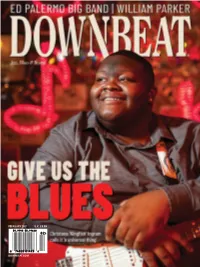

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Exploring a New Model for Emerging Musical Artists by Jay Cohen

Losing the Label: Exploring A New Model for Emerging Musical Artists by Jay Cohen An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2010 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Yannis Bakos Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor Abstract After an examination of a traditional recording contract model, an updated framework is developed such that the recording artist may take advantage of current technology enabling them to perform certain actions formerly reserved to the label. The updated framework provides that emerging technology will create the ability for some new musical groups to become popular and create equal levels of revenue without a recording label. A formula to weigh the decision whether or not to use a label is developed. Introduction The economic frameworks used to analyze the music industry have become more complicated as the industry has changed; due to technological changes, the scope of today‟s market is in drastic need of an update. Because of huge shifts in technology and capacity, the model must be re-analyzed in order to best understand the optimal decisions for bands. The general market structure is five major labels and a large number of independent, or „indie‟, labels; these form two interdependent markets that interact with one another. The business venture of the label is to take on levels of risk that results in an optimal reward if the band is successful. The number of risks taken is a product of the compensation packages offered to the artists, as well as the percentage of profit gathered for each artist‟s contract. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT