Haiti @ the Digital Crossroads: Archiving Black Sovereignty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Overview Strategic Funding .................................................................................................................. 2 Arts Discipline Funding ......................................................................................................... 3 Loan Fund ............................................................................................................................. 4 Operations ............................................................................................................................. 5 Preliminary Results of Increased Grants Funding ............................................................................. 6 2013 Allocations Summary ................................................................................................................ 7 Income Statement & Program Balances for the quarter ended December 31, 2013 ........................ 8 Strategic Funding 2013 Partnership Programs .......................................................................................................... 9 Strategic Partnerships ........................................................................................................... 10 Strategic Allocations .............................................................................................................. 11 Recipient Details .................................................................................................................. -

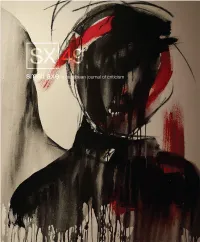

0-SMX43 FM (Ix)

EDITOR MANAGING EDITOR ADVISORY BOARD David Scott Vanessa Agard‑Jones Edward Baugh Kamau Brathwaite EDITORIAL COMMITTee EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Erna Brodber Yarimar Bonilla Nijah Cunningham Edouard Duval Carrié Charles Carnegie Rhonda Cobham Kaiama L. Glover PRODUCTION Edwidge Danticat Erica James MANAGER/ J. Michael Dash Aaron Kamugisha COPYEDITOR Locksley Edmondson Roshini Kempadoo Kelly S. Martin Stuart Hall Martin Munro Robert Hill Melanie Newton TRANSLATOR, FRENCH George Lamming Matthew Smith Nadève Ménard Kari Levitt Rupert Lewis COPYEDITOR, FRENCH Earl Lovelace Alex Martin Sidney Mintz Sandra Pouchet Paquet GRAPHIC DESIGNER Caryl Phillips Juliet Ali Gordon Rohlehr Verene Shepherd Maureen Warner‑Lewis Sylvia Wynter The Small Axe Project consists of this: to participate both in the renewal of practices of intellectual criticism in the Caribbean and in the expansion/revision of the horizons of such criticism. We acknowledge of course a tradition of social, political, and cultural criticism in and about the regional/diasporic Caribbean. We want to honor that tradition but also to argue with it, because in our view it is in and through such argument that a tradition renews itself, that it carries on its quarrel with the generations of itself: retaining/revising the boundaries of its identity, sustaining/ altering the shape of its self‑image, defending/resisting its conceptions of history and community. It seems to us that many of the conceptions that guided the formation of our Caribbean modernities—conceptions of class, gender, nation, culture, race, for example, as well as conceptions of sovereignty, development, democracy, and so on—are in need of substantial rethinking. What we aim to do in our journal is to provide a forum for such rethinking. -

Mapping Caribbean Cyberfeminisms

1 1 Mapping Caribbean Cyberfeminisms Tonya Haynes Caribbean cyberfeminisms are diverse, heterogeneous, and polyvocal. Net- works may be simultaneously national, regional, global, transnational, and dias- poric.Through practices of media creation, curating, (re)blogging, (re)tweeting, sharing, and commenting across multiple social media platforms, Caribbean fem- inist knit together an online community that is often linked to on-the-ground or- ganizing and action. Online feminist practices are therefore rich archives for the study of Caribbean feminisms. To date, scholarly work on women’s and feminist movements in the region has failed to document and analyze these practices and sites of activism. Similarly, Caribbean feminist critiques of technology and new me- dia are not well developed.The essay attends to this gap by offering a partial and preliminary mapping Caribbean cyberfeminisms primarily through documentation and analysis of Caribbean feminist blogs. The murder of Japanese pannist Asami Nagakiya at Trinidad and Tobago’s carni- val generated international headlines.The mayor of Port of Spain, Raymond Tim Kee, seemed to blame Nagakiya for her own death, couching the violence against her as a result of “vulgarity and lewdness in conduct,” underscoring that “women have a respon- sibility to ensure they are not abused.”1 Trinidadian women (and men) assembled outside City Hall to demand the mayor’s resignation.They also shifted the public conversation on gender-based violence away from what they deemed “victim-blaming” and “slut- shaming” toward one of state accountability and respect for women’s autonomy and bodily integrity. The leaders of the feminist organization womantra2 were among those 1 Sean Douglas,“Mayor: Beware Dangerous Sub-cultures,” Trinidad and Tobago Newsday, 11 February 2016, http://www.newsday.co.tt/news/0,223841.html. -

QUE E R'l ,,,\ Limitof

OHIO I ST.\TE the I • QUE E R'l ,,,\ LIMITof ,, BLACI< MEMORY BLACK LESBIAN LITERATURE AND IRRESOLUTION MATT RICHARDSO J. II I : CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Listening to the Archives: Black Lesbian Literature and Queer Memory 1 CHAPTER 1 Desirous Mistresses and Unruly Slaves: Neo-Slave Narratives, Property, Power, and Desire 21 CHAPTER 2 Small Movements: Queer Blues Epistemologies in Cherry Muhanji's Her 57 CHAPTER 3 "Mens Womens Some that is Both Some That is Neither": Spiritual Epistemology and Queering the Black Rural South in, the Work of Sharon Bridgforth 83 CHAPTER 4 "Make It Up and Trace It Back": Remembering Black Trans Subjectivity in Jackie Kay's Trumpet 107 CHAPTER 5 What Grace Was: Erotic Epistemologies and Diasporic Belonging in Dionne Brand's In Another Place, Not Here 136 EPILOGUE Grieving the Queer: Anti-Black Violence and Black Collective Memory 159 169 Notes 199 Index INTRODUCTION Listening to the Archives Black Lesbian Literature and Queer Memory he Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) is a recent structure that has emerged as a monument to Black mem- ory. Opened in San Francisco in December of 2005, the museum is literally positioned between archives. Located near Union Square, the museum stands across the street from the Cali- fornia Historical Society, and a few doors down from, the San Francisco Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender (GLBT) Archives. Each one of these institutions holds pieces of Black history, but there is no single structure that houses a satisfactory story. For a Black queer subject like me, standing between these institutions brings into stark relief the fractured and incomplete nature of the archives. -

Ay 2017-2018

THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS INSTITUTE FOR GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ST. AUGUSTINE UNIT REPORT TO THE REGIONAL PLANNING AND STRATEGY COMMITTEE FOR THE PERIOD MAY 31, 2017 TO JUNE 1, 2018 FOR THE FACE TO FACE MEETING JUNE 13 AND 14, 2018 CAVE HILL CAMPUS, BARBADOS Group photo with visitors to the Institute, Ms Usha Maharaj, business woman and partner of Chancellor Bermudez, and the University Director of the IGDS, Prof. Opal Palmer Adisa. Also in photo Professor Rhoda Reddock, Dr. Gabrielle Hosein, and IGDS staff and graduate students. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2–9 MILESTONES 10 Understanding the UWI brand as Activist University 2 Reflection 9 TEACHING AND LEARNING 11–14 Undergraduate Teaching for Reporting Period 11 Graduate Teaching for Reporting Period 12 Short Courses - Summer Teaching 12 Graduates | Graduate Programme Achievements 13 Graduate Research Seminars 14 RESEARCH AND PUBLICATIONS 15–17 Caribbean Review of Gender Studies - Online Journal 15 Making of Feminisms in the Caribbean 16 Edited Collections - Books 17 Edited Collections - Journals 18 – 20 RESEARCH AND OUTREACH 21–26 Research Projects 21 – 23 Networks 24 – 26 OUTREACH ACTIVITIES AND EVENTS 27–34 Symposia | Public Fora | Lunchtime Seminars 27 – 29 Workshops and Presentations 30 Collaborations: Significant Days / Activism 31 – 33 Collaborations: Partnerships 34 OUTREACH AND MOBILIZATION 35–38 IGDS Streams: Reach, Next, Ignite, Gold, CV+, Future Fund, Impact 35 – 38 APPENDIX I - IGDS STAFFING 2016/2017 39 APPENDIX II - STAFF PROFILES 40 Dr. Gabrielle Hosein – Lecturer and Head of Institute 41 – 45 Prof Patricia Mohammed – Professor of Gender and Cultural Studies 46 – 50 Prof. -

Submerged Bodies the Tidalectics of Representability and the Sea in Caribbean Art

Submerged Bodies The Tidalectics of Representability and the Sea in Caribbean Art ELIZABETH DELOUGHREY Department of English and the Institute for the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, USA TATIANA FLORES Departments of Latino and Caribbean Studies and Art History, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, USA Dedicated to Tony Capellán (1955–2017) and Kamau Brathwaite (1930–2020) Dès la plus lointaine enfance (From the very beginning) la mer te met en accord cosmique (the sea puts you in cosmic harmony) avec les êtres, les lieux, les plantes, (with all beings, all places) les animaux, les pierres, les pluies (all plants and animals, rocks and rain) et les fables enchantées du monde (and all of the world’s enchanting stories). —René Depestre, “Mère caraïbe” (Caribbean Mother), translated by Anita Sagátegui Abstract Recent scholarship in the blue humanities, or critical ocean studies, has turned to the mutable relationship between human bodies and the ocean, shifting from depictions of a seascape across which human bodies attain agency to considering the experience and rep- resentability of sea ontologies, wet matter, and transcorporeal engagements with the more- than-human world. This work generally focuses on a universalized ocean (as nonhuman na- ture) rather than a geographically and culturally specific place (as history). The authors’ work turns the visual focus from the surface to the depths, engaging with the Caribbean Sea and contemporary artists who depict a gendered oceanic intimacy and aesthetics of diffrac- tion and submergence. Building upon the 2017 exhibition Relational Undercurrents: Contempo- rary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago, curated by Tatiana Flores, this article expands the con- versation from the archipelagic to the submarine, engaging “tidalectic” representations of underwater bodies through ontologies and aesthetics of diffraction. -

Contributors

CONTRIBUTORS 110 ANNA MARIELLE NIJAH ARABINDAN-KESSON BARROW CUNNINGHAM ANNA ARABINDAN-KESSON is an assistant MARIELLE BARROW is a Fulbright Scholar, social NIJAH CUNNINGHAM is an assistant professor of professor of black diaspora art, jointly appointed entrepreneur, and visual artist. Her research inves- English at Hunter College, City University of New in the departments of African American Studies tigates the formation of countercultural memory York. His teaching and research focus on issues and Art and Archaeology at Princeton University. and cultural capital across Caribbean artistic of time and aesthetics in twentieth-century African Born in Sri Lanka, she also trained and practiced practice, which she translates into practical American and African diasporic literature and as a registered nurse in Australia, New Zealand, intervention through the 3rd Saturdayz curatorial culture. He is currently working on a book man- and England. Her first book, Black Bodies, White project in which visual and performance artists uscript titled “Quiet Dawn,” which considers the Gold: Art, Cotton, and Commerce in the Atlantic intervene in national discussions. She has worked ambiguous legacies of black and anticolonial rev- World, is under contract with Duke University across the Caribbean and in the United States olutionary politics. His work has appeared in Small Press. Along with Mia Bagneris (Tulane Univer- and Africa in cultural programming and as a cre- Axe, Women and Performance, and the New In- sity), she was awarded an ACLS Collaborative ative industries consultant. In 2010 she initiated quiry. He has also curated exhibitions, such Research Fellowship for a new book project, the Caribbean InTransit project, an arts education, as Hold: A Meditation on Black Aesthetics (Princ- “Beyond Recovery: Reframing the Dialogues of open-access, peer-reviewed journal of Caribbean eton University Art Museum, 2018). -

The Literature of Catastrophe in the Francophone Caribbean

Copyright 2015 Daniel Brant GEOGRAPHIES OF SUFFERING: THE LITERATURE OF CATASTROPHE IN THE FRANCOPHONE CARIBBEAN BY DANIEL BRANT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jean-Philippe Mathy, Chair Professor H. Adlai Murdoch, Director of Research Associate Professor Margaret C. Flinn Associate Professor Patrick M. Bray ABSTRACT In the context of climate change and increasing vulnerability to catastrophe across the globe, this dissertation investigates the political, historical, and cultural stakes of disasters in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Haiti from the nineteenth century to the present. In so doing, it examines how Caribbean writers respond to the political and social challenges that disasters pose using methodologies from literary criticism, cultural studies, and historical analysis. Attending closely to representation, textuality, and shifting historical contexts, this study analyzes major works by French, Martinican, Guadeloupean, and Haitian writers including Voltaire, Victor Schœlcher, Aimé Césaire, Maryse Condé, and Yanick Lahens alongside other primary sources like travelogues and administrative reports. Developed across four chapters, it makes three significant contributions to Caribbean studies while illuminating theoretical discussions in postcolonial studies, ecocriticism, and disaster studies. First, it underscores the role that the continual risk of natural catastrophe has played in Caribbean history and thought. Second, this project demonstrates how Francophone writing since the Haitian Revolution (1791- 1804) has refashioned catastrophe into a valuable critical framework for reconsidering the Caribbean from within and without. Third, it reveals how this “literature of catastrophe” rethinks domination in the region and articulates new discourses on culture, memory, and identity. -

Caribbean Queer Visualities David Scott

curated by David Scott E rica Moiah James Nijah Cunningham 04 David Scott Caribbean Queer Visulaties 08 16 28 / 44 58 andilGOSINE ebonyG.PATTERSON jean-ulrickDESERT jorgePINEDA charlLANDVREUGD Between the Leaves and in Neque mittatis margaritas Vestra Coolie Colors Giguapa Movt nr. 8: The quality of 21 the Bed ante porcos (Do Not Cast Pearls In a Field of Butterflies Before Swine) Laying in a Bush of Things 10 From the Corner of your Eye 46 60 Maja Horn Rosamond S. King Vanessa Agard-Jones 30 Jorge Pineda’s Queer Visualities? Where Trauma Resides When We Start Thinking: 18 Jerry Philogene Postcolonial Sexualities and Charl Landvreugd’s Multivalent Diasporic Queering and Antinormativity Afropean Aesthetic Nadia Ellis Intimacies of the Creole Being Obscure; or, The Queer Light of Ebony G. Patterson 2 72 84 100 114 128 richardFUNG leoshoJOHNSON nadiaHUGGINS kareemMORTIMER ewanATKINSON First Generation Promised Land Is That a Buoy? Witness Select Pages from the Fieldnotes of Dr. Tobias Boz, Anthrozoologist 74 86 102 Terri Francis Patricia Joan Saunders Angelique V. Nixon 116 130 Unpretty Disruptions: “Church inna Session”: Troubling Queer Caribbeanness: Roshini Kempadoo Listening and Queering the Leasho Johnson, Mapping the Embodiment, Gender, and Troubling an Unjust Present: Jafari S. Allen Visual in Richard Fung’s Sacred through the Profane in Sexuality in Nadia Huggins’s Kareem Mortimer’s Filmmaking A Queer Decipherment of Select Videotapes Jamaican Popular Culture Visual Art Ambition for The Bahamas Pages from the Fieldnotes of Dr. Tobias Boz, Anthrozoologist 140 Erica Moiah James Afterword 142 Acknowledgements 144 Contributors 3 Caribbean Queer Visualities David Scott One of the most remarkable developments in the Caribbean and its diaspora over the past two decades or so is the emergence of a generation of young visual artists working in various media (paint, film, performance) who have been transforming Caribbean visual practice, perhaps even something larger like Caribbean visual culture. -

2017-2018 Report

The Society of Fellows in the Humanities Annual Report 2017–2018 Society of Fellows Mail Code 5700 Columbia University 2960 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Phone: (212) 854-8443 Fax: (212) 662-7289 [email protected] www.societyoffellows.columbia.edu By FedEx or UPS: Society of Fellows 74 Morningside Drive Heyman Center, First Floor East Campus Residential Center Columbia University New York, NY 10027 Posters courtesy of designers Amelia Saul and Sean Boggs Contents Report From The Chair 5 Special Events 33 • New Books in the Society of Fellows 36 Members of the 2017–2018 Governing Board 8 • Explorations in the Forty-Third Annual Fellowship Competition 9 Medical Humanities 38 Fellows in Residence 2017–2018 11 Heyman Center Events 43 • Joelle M. Abi-Rached 12 • Event Highlights 44 • Christopher M. Florio 13 • Public Humanities Initiative 52 • David Gutkin 14 • Heyman Center Series and Workshops 54 • Heidi Hausse 15 Politics of the Present 54 • Arden Hegele 16 Uprising 13/13 Seminar Series 55 • Lauren Kopajtic 17 New Books in the Arts and Sciences 55 • Whitney Laemmli 18 • María González Pendás 19 Heyman Center Fellows 2017–2018 59 • Carmel Raz 20 Alumni Fellows News 63 Thursday Lectures Series 21 In Memoriam 65 • Fall 2017: Fellows’ Talks 23 Alumni Fellows Directory 67 • Spring 2018: “Supernatural” 26 2017–2018 Fellows at the annual year-end Spring gathering (from left): Heidi Hausse (2016–2018), Arden Hegele (2016–2019), Lauren Kopajtic (2017–2018), Whitney Laemmli (2016–2019), Christopher Florio (2016–2019), Carmel Raz (2015–2018), David Gutkin (2015–2017), and Joelle M. Abi-Rached (2017–2019). -

Small Axe 49: "Sylvia Wynter's “Black Metamorphosis”: A

Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism is published in March, July, and November by Duke University Press, 905 W. Main St., Suite 18B, Durham, NC 27701, on behalf of Small Axe, Inc. Number 49 corresponds to vol. 20, no. 1, 2016. Submissions/correspondence Manuscripts of no more than 7,000 words should be submitted electronically as MS Word attachments to [email protected]. For style details, please consult www.smallaxe.net/smallaxe/submission.php. Visual materials should be sent to [email protected] and must be accompanied by clear layout instructions. A synopsis of Small Axe submission guidelines is provided at www.dukeupress.edu/smallaxe. World Wide Web Visit Small Axe at www.smallaxe.net and Duke University Press Journals at www.dukeupress.edu/journals. Subscriptions Direct all orders to Duke University Press, Journals Customer Relations, 905 W. Main St., Suite 18B, Durham, NC 27701. Permissions Photocopies for course or research use that are supplied to the end user at no cost may be made without explicit permission or Annual subscription rates: print-plus-electronic institutions, $175; fee. Photocopies that are provided to the end user for a fee may not print-only institutions, $160; e-only institutions, $136; individuals, $35; be made without payment of permission fees to Duke University Press. students, $25. Address requests for permission to republish copyrighted material to Rights and Permissions Manager, [email protected]. For information on subscriptions to the e-Duke Journals Scholarly Collections, contact [email protected]. Advertising Direct inquiries about advertising to Journals Advertising Coordinator, [email protected]. Print subscriptions: add $11 postage and applicable HST (including 5% GST) for Canada; add $14 postage outside the US and Canada. -

Vol. 26 / No. 1 / April 2018 Volume 26 Number 1 April 2018 Lisa Outar, Editor in Charge

Vol. 26 / No. 1 / April 2018 Volume 26 Number 1 April 2018 Lisa Outar, Editor in Charge Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Expulsion 2 by Portia Subran Lisa LaFramboise (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt.