Albertsons-Safeway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Store & Service Guide

Be Union, Shop Union – Support Your Fellow Local 5 Members If union members don’t support union businesses how can we expect the general public to do so? Resist the urge to pick up a “deal” at a non-union store where low wages and sub-standard working conditions create unfair competition for your employer and ultimately, threaten your contract and possibly your job. Patronize the following union stores and businesses: GROCERY STORES Safeway Stores – All Northern California stores Lucky Stores – All Northern California stores Nob Hill Stores – All Bay Area stores except Monroe St., Santa Clara Food Maxx – All Northern California stores Al’s Food Market, Castro Valley Bianchini’s Market, San Carlos Bianchini’s Market, Portola Valley Bruno’s Food Center, Carmel (meat only) DeLano Market, Fairfax Deluxe Foods, Aptos Diablo Foods, Lafayette Draeger’s, Menlo Park Draeger’s, Los Altos Harvest Market, Fort Brag Draeger’s, Danville Key Market, Redwood City Draeger’s, South San Francisco Lunardi’s, South San Francisco Encinal Market, Alameda Lunardi’s, San Bruno Fairway Market, Salinas Lunardi’s, Los Gatos Fairway Market, Gonzales Lunardi’s, San Jose Fairway Market, Watsonville Lunardi’s, Belmont Food Mill, Oakland Lunardi’s, Walnut Creek Food Source, Hayward Lunardi’s, Burlingame Foods Co, San Francisco Lunardi’s, Danville Foods Co, Richmond Mal’s Market, Seaside (meat only) Foods Co, Pittsburg Marin Scotty’s Market, San Rafael Foods Co, Salinas Mill Valley Market, Mill Valley Grocery Outlet, Oakland Mollie Stone’s, Sausalito Grocery Outlet, Redwood -

Calling All Emerging/Challenger Brands

September 26 – 28, 2021 | Palm Springs, California CALLING ALL EMERGING/CHALLENGER BRANDS What is an Emerging Brand: California retailers have a fondness for new boutique products that are just beginning to introduce themselves to the consumer market. These brands often offer unique product characteristics, a strong appeal to the niche consumer markets and demonstrates high growth potential. Increasingly, these brands also offer retailers a distinctive point of differentiation from their competition. Benefits: • Educational webinar series – Road to Retail, “How Emerging Brands Can Get on the Shelf” 15-20 minute sessions (see details included) • Pre-Scheduled 20-minute meetings with retailers • Complete list of participating retailers including full contact information • ¼-page four (4) colored advertisement in the conference issue of the California Grocer magazine • Company listing on conference website Bundle • Company listing on conference mobile app Valued at • Two (2) complimentary registrations (includes Educational Program, Monday and Tuesday’s Breakfast and Lunch, Conference Receptions and $20,000 After Hours Social) • White Board Session focused on Emerging Brands • Emerging Brands sample center (certain limitations apply) Sponsorship Package: $5,000 Participating Retailers Albertsons/Safeway/Vons/Pavilions North State Grocery (Holiday & SavMor) Big Saver Foods, Inc. Numero Uno Markets Bristol Farms/Lazy Acres Nutricion Fundamental, Inc. Cardenas Markets Raley’s C&K Markets (Ray’s Food Place, Shop Smart) Ralphs Grocery Company -

Lidl Expanding to New York with Best Market Purchase

INSIDE TAKING THIS ISSUE STOCK by Jeff Metzger At Capital Markets Day, Ahold Delhaize Reveals Post-Merger Growth Platform Krasdale Celebrates “The merger and integration of Ahold and Delhaize Group have created a 110th At NYC’s Museum strong and efficient platform for growth, while maintaining strong business per- Of Natural History formance and building a culture of success. In an industry that’s undergoing 12 rapid change, fueled by shifting customer behavior and preferences, we will focus on growth by investing in our stores, omnichannel offering and techno- logical capabilities which will enrich the customer experience and increase efficiencies. Ultimately, this will drive growth by making everyday shopping easier, fresher and healthier for our customers.” Those were the words of Ahold Delhaize president and CEO Frans Muller to the investment and business community delivered at the company’s “Leading Wawa’s Mike Sherlock WWW.BEST-MET.COM Together” themed Capital Markets Day held at the Citi Executive Conference Among Those Inducted 20 In SJU ‘Hall Of Honor’ Vol. 74 No. 11 BROKERS ISSUE November 2018 See TAKING STOCK on page 6 Discounter To Convert 27 Stores Next Year Lidl Expanding To New York With Best Market Purchase Lidl, which has struggled since anteed employment opportunities high quality and huge savings for it entered the U.S. 17 months ago, with Lidl following the transition. more shoppers.” is expanding its footprint after an- Team members will be welcomed Fieber, a 10-year Lidl veteran, nouncing it has signed an agree- into positions with Lidl that offer became U.S. CEO in May, replac- ment to acquire 27 Best Market wages and benefits that are equal ing Brendan Proctor who led the AHOLD DELHAIZE HELD ITS CAPITAL MARKETS DAY AT THE CITIBANK Con- stores in New York (26 stores – to or better than what they cur- company’s U.S. -

PGY1 Community-Based Pharmacy Residency Program Chicago, Illinois

About Albertsons Companies Application Requirements • Albertsons Companies is one of the largest food and drug • Residency program application retailers in the United States, with both a strong local • Personal statement PGY1 Community-Based presence and national scale. We operate stores across 35 • CV or resume states and the District of Columbia under 20 well-known Pharmacy Residency Program banners including Albertsons, Safeway, Vons, Jewel- • Three electronic references Chicago, Illinois Osco, Shaw’s, Haggen, Acme, Tom Thumb, Randalls, • Official transcripts United Supermarkets, Pavilions, Star Market and Carrs. • Electronic application submission via Our vision is to create patients for life as their most trusted https://portal.phorcas.org/ health and wellness provider, and our mission is to provide a personalized wellness experience with every patient interaction. National Matching Service Code • Living up to our mission and vision, we have continuously 142515 advanced pharmacist-provided patient care and expanded the scope of pharmacy practice. Albertsons Companies has received numerous industry recognitions and awards, Contact Information including the 2018 Innovator of the Year from Drug Store Chandni Clough, PharmD News, Top Large Chain Provider of Medication Therapy Management Services by OutcomesMTM for the past 3 Residency Program Director years, and the 2018 Corporate Immunization Champion [email protected] from APhA. (630) 948-6735 • Albertsons Companies is pleased to offer residency positions by Baltimore, Boise, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Portland, and San Francisco. To build upon the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) education and outcomes to develop www.albertsonscompanies.com/careers/pharmacy-residency-program.html community‐based pharmacist practitioners with diverse patient care, leadership, and education skills who are eligible to pursue advanced training opportunities including postgraduate year two (PGY2) residencies and professional certifications. -

Testimony of Karl Langhorst Director, Loss Prevention Randall's /Tom

Testimony of Karl Langhorst Director, Loss Prevention Randall’s /Tom Thumb a Safeway Company before the House Judiciary Committee Crime Subcommittee’s hearing “Organized Retail Theft: Fostering a Comprehensive Public-Private Response” October 25, 2007 10:00 a.m. 2141 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Testimony of Karl Langhorst Director, Loss Prevention Randall’s /Tom Thumb a Safeway Company before the House Judiciary Committee Crime Subcommittee October 25, 2007 Chairman Conyers, Chairman Scott, Congressmen Smith and Forbes, and members of the committee, good morning. Thank you for the opportunity to testify before the Crime Subcommittee today on the growing problem of organized retail crime. My name is Karl Langhorst, Director of Loss Prevention for Randall’s/Tom Thumb of Texas, a division of Safeway. Safeway Inc. is a Fortune 100 company and one of the largest food and drug retailers in North America. The company operates 1,738 stores in the United States and western Canada and had annual sales of $40.2 billion in 2006. I have been invited here to share with you our experience with the increasing problem of organized retail crime (ORC). Retailers have always had to deal with shoplifting as part of doing business, but let me be clear, ORC is not shoplifting. It is theft committed by professionals, in large volume, for resale. It is being committed against retailers of every type at an increasing rate. Safeway estimates a loss of $100 million dollars annually due to ORC. According to the FBI, the national estimate is between $15-30 billion annually. Let me describe for you how sophisticated and organized these enterprises are. -

Permit Num Retail Name Address City RS-0055-21 Albertsons 0131 1410

Cancell Sales Last Name Sales First ZIP County In Out Tent Stand Wholesaler 1 Wholesaler 2 Wholesaler 3 Wholesaler 4 Wholesaler 5 Sales Location ed Permit Retail Name Address City Num Name Fire Dept RS-0055-21 Albertsons 0131 Shriner Sarah 1410 W Park Plaza Ontario 97914 Malheur TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American ONTARIO F&R Promotional Events NW RS-0331-21 Albertsons 0505 Onchi Chad 5415 SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy Portland 97221 Multnomah TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American PORTLAND F&R Promotional Events NW RS-0340-21 Albertsons 0513 Walline Jenni 4740 Royal Ave Eugene 97402 Lane TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American EUGENE Promotional Events SPRINGFIELD NW FIRE RS-0058-21 Albertsons 0515 Patterson Michelle 3013 NW Stewart Parkway Roseburg 97471 Douglas TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American ROSEBURG FD Promotional Events NW RS-0562-21 Albertsons 0536 Maglnigal Danielle 25691 SE Stark St Troutdale 97060 Multnomah TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American GRESHAM FIRE Promotional Events & EMERG SRVCS NW RS-0563-21 Albertsons 0564 Dehann Jannine 451 NE 181st St Portland 97230 Multnomah TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American GRESHAM FIRE Promotional Events & EMERG SRVCS NW RS-0056-21 Albertsons 0571 Rainsier Mark 19007 S Beavercreek Rd Oregon City 97045 Clackamas TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American CLACKAMAS CO Promotional Events FIRE DIST #1 NW RS-0339-21 Albertsons 0572 Souliyalaovong Ruby 311 Coburg Rd Eugene 97401 Lane TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE American EUGENE Promotional Events SPRINGFIELD NW FIRE RS-0338-21 Albertsons 0574 Vails Tracey 5755 Main St Springfield 97478 Lane TRUE -

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study Fall 2020 Georgetown University Law Center Professor Dale Collins ALBERTSONS/SAFEWAY CASE STUDY Table of Contents The deal Safeway Inc. and AB Albertsons LLC, Press Release, Safeway and Albertsons Announce Definitive Merger Agreement (Mar. 6, 2014) .............. 4 The FTC settlement Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Requires Albertsons and Safeway to Sell 168 Stores as a Condition of Merger (Jan. 27, 2015) .................................... 11 Complaint, In re Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. C-4504 (F.T.C. filed Jan. 27, 2015) (challenging Albertsons/Safeway) .................... 13 Agreement Containing Consent Order (Jan. 27, 2015) ................................. 24 Decision and Order (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ...................... 32 Order To Maintain Assets (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ............ 49 Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Orders To Aid Public Comment (Nov. 15, 2012) ........................................................... 56 The Washington state settlement Complaint, Washington v. Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. 2:15-cv-00147 (W.D. Wash. filed Jan. 30, 2015) ................................... 69 Agreed Motion for Endorsement of Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ........... 81 [Proposed] Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ............................................ 84 Exhibit A. FTC Order to Maintain Assets (omitted) ............................. 100 Exhibit B. FTC Order and Decision (omitted) ..................................... -

Safeway Fact Book 2006

About the Safeway Fact Book This Fact Book provides certain financial and operating information about Safeway. It is intended to be used as a supplement to Safeway’s 2005 Annual Report on Form 10-K, quarterly reports on Form 10-Q and current reports on Form 8-K, and therefore does not include the Company’s consolidated financial statements and notes. Safeway believes that the information contained in this Fact Book is correct in all material respects as of the date set forth below. However, such information is subject to change. May 2006 Contents I. Investor Information Page 2 II. Safeway at a Glance Page 4 III. Retail Operations Page 5 IV. Retail Support Operations Page 8 V. Finance and Administration Page 12 VI. Financial and Operating Statistics Page 25 VII. Directors and Executive Officers Page 28 VIII. Corporate History Page 29 Note: This Fact Book contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Exchange Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Such statements relate to, among other things, capital expenditures, identical-store sales, comparable-store sales, cost reductions, operating improvements, obligations with respect to divested operations, cash flow, share repurchases, tax settlements, information technology, Safeway brands and store standards and are indicated by words or phrases such as “continuing”, “on going”, “expects”, “plans”, “will” and similar words or phrases. These statements are based on Safeway’s current plans and expectations and involve risks and uncertainties that could cause actual events and results to vary significantly from those included in, or contemplated or implied by such statements. -

PI Setup & Steps for Success

PI Setup & Steps for Success Below is a high-level checklist to assist you with Product Introduction (PI) setup and new item submission. Detailed information is provided in the free Albertsons PI Supplier Training Modules under ‘Education’ on the Albertsons Companies Landing Site at: www.1worldsync.com/albertsons □ Must have a 6-digit Vendor Number and 3-digit Sub Account/Outlet setup in the Albertsons Companies system o Unsure? Contact your Albertsons Companies Sales Merchandising Team o The Sales Merchandising Team must approve supplier setup. More details located at: http://suppliers.safeway.com/pages/BecomeASupplier.htm □ Locate or create your Global Location Number (GLN) (unique identifier) o Suppliers: . Unsure? Contact 1WorldSync at 866-280-4013 or [email protected] . Need to setup a GLN? Contact GS1 at 937-435-3870 or [email protected] . Exclusion applies for Alcohol and Own Brands/Private Label o Brokers: . Ask your supplier to provide the GLN □ PI access o Next step depends on your company’s current engagement . GDSN: 1WorldSync customer (GDSN = Global Data Synchronization Network) . GDSN: Other data pool . Non-GDSN: Existing Account . Non-GDSN: New Account . Broker: Brand owner must give the broker access to PI under their GLN □ If your company already has access to PI o Ask your company administrator to grant you access to PI □ If you don’t have access to PI o GDSN/1WorldSync Customer: contact 1WorldSync at 866-280-4013 or [email protected] o Alcohol entities: Contact 1WorldSync Business Development at 866-280-4013 or [email protected] o Own Brands/Private Label: Contact your Albertsons Companies Own Brands team o Own Brands/Supply-Expense: Contact 1WorldSync Business Development at 866-280-4013 or [email protected] o GDSN/Other Data Pool or Non-GDSN (Fee Based System) . -

Agtnum Agent Name Agent Address Agent City

AGTNUM AGENT_NAME AGENT_ADDRESS AGENT_CITY STATE ZIP 10175 FIDDLE STIX 6501 GLENWOOD AVE RALEIGH NC 27612 12983 BILL PAYMENT CENTER 215 W MARTIN ST RALEIGH NC 27601 13497 FOOD LION #253 570 RIVERBEND DR CHARLOTTESVILLE VA 22911 13498 FOOD LION #484 501 EAST MAIN ST LOUISA VA 23093 13499 FOOD LION #864 1740 TIMBERWOOD BLVD CHARLOTTESVILLE VA 22911 13501 FOOD LION #870 15105 PATRICK HENRY HWY AMELIA COURT HOUSE VA 23002 13502 FOOD LION #940 136 CEDAR GROVE RD RUCKERSVILLE VA 22968 13504 FOOD LION #959 264 TURKEYSAG TRL PALMYRA VA 22963 13506 FOOD LION #1186 585 BRANCHLANDS BLVD CHARLOTTESVILLE VA 22901 13507 FOOD LION #1298 408 W GORDON AVE GORDONSVILLE VA 22942 13508 FOOD LION #1361 2105 ACADEMY RD POWHATAN VA 23139 13509 FOOD LION #1402 577 MADISON RD ORANGE VA 22960 13510 FOOD LION #1531 85 CALOHILL DR LOVINGSTON VA 22949 13511 FOOD LION #1536 32 MILL CREEK DR CHARLOTTESVILLE VA 22902 13515 FOOD LION #1576 38 S CONSTITUTION RD DILLWYN VA 23936 13516 FOOD LION #2567 46 MADISON PLAZA DR MADISON VA 22727 13519 FOOD LION #297 9157 STAPLES MILL RD RICHMOND VA 23228 13524 FOOD LION #299 11130 HULL STREET RD MIDLOTHIAN VA 23112 13529 FOOD LION #478 8201 HULL STREET RD RICHMOND VA 23235 13531 FOOD LION #514 1288 CONCORD AVE RICHMOND VA 23228 13532 FOOD LION #545 11 DUNLOP VLG COLONIAL HEIGHTS VA 23834 13533 FOOD LION #601 3089 MECHANICSVILLE TPKE RICHMOND VA 23223 13538 FOOD LION #620 15702 JEFFERSON DAVIS HW COLONIAL HEIGHTS VA 23834 13540 FOOD LION #623 8006 BUFORD CT RICHMOND VA 23235 13541 FOOD LION #628 9502 CHAMBERLAYNE RD MECHANICSVILLE -

ECRM Ad Comparisons the LEADING PROVIDER of PROMOTIONAL DATA and BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE St

ECRM Ad Comparisons THE LEADING PROVIDER OF PROMOTIONAL DATA AND BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE St. Patrick’s Day Promotional Review 2013 versus 2014 Confidential and Proprietary to ECRM 1 METHODOLOGY Effective Ad Count Used in Study: Effective Ad Count gives partial credit to any product that shares an ad block with other products in order to provide more context in promotional analysis. For example: If 4 products are present in an ad block each will only receive a .25 count for that particular promotion. If 3 products are present each one receives .33 count. Time Periods: Current Year: 2/16/2014 - 3/22/2014 Prior Year: 2/17/2013 - 3/23/2013 Retailers Used in Representative Market Review: A & P, Albertson's - SoCal (SVU), Albertsons SOC, CVS, Dollar General, Family Dollar, Food Lion, Giant Eagle, Giant Food Landover, H.E.B., Jewel-Osco (NAI), Jewel-Osco (SVU), Kmart, Kroger CIN, Meijer, Rite Aid, Safeway Stores, Stater Bros, Super 1 Foods, Target Stores, Walgreens, Walmart-US, Winn Dixie. Representative Markets Used. Retailers Used in Promoted Price Study: Chicago Market Retailers: CVS, Dominick's Finer Foods, Food 4 Less, Meijer, Strack & Van Til, Target Stores, Ultra Foods. Media Type: Circular Promotions. Sampling Methodology: A typical basket of St. Patrick’s Day items was developed using the following categories: Beef, Cheese, Cheese Chunk/Block, Cordial, Deli Beef/Roast Beef, Deli Cheese, Dry Potatoes, Fingerling Potatoes, Fresh Cut Flowers, Grated Cheese, Imported Beer, Irish Whiskey, Other Vegetables, Petite Potatoes, Potato Chips, Red Potatoes, Russet Potatoes, Specialty Cheeses, White Potatoes, Yellow Potatoes and Bakery In-Store. The basket was used to identify pages containing St. -

Alabama Vendor List.Xlsx

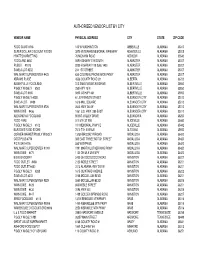

AUTHORIZED VENDOR LIST BY CITY VENDOR NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE FOOD GIANT #716 100 W WASHINGTON ABBEVILLE ALABAMA 36310 SUPER DOLLAR DISCOUNT FOODS 3970 VETERANS MEMORIAL PARKWAY ADAMSVILLE ALABAMA 35005 HYATT'S MARKET INC 70 MCHANN ROAD ADDISON ALABAMA 35540 FOODLAND #450 509 HIGHWAY 119 SOUTH ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 PUBLIX #1073 9200 HIGHWAY 119 Suite 1400 ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 SAVE-A-LOT #202 244 1ST STREET ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #423 630 COLONIAL PROMENADE PKWY ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 ABRAMS PLACE 4556 COUNTY ROAD 29 ALBERTA ALABAMA 36720 ALBERTVILLE FOODLAND 313 SAND MOUNTAIN DRIVE ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #500 250 HWY 75 N ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 SAVE-A-LOT #165 5850 US HWY 431 ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #238 61 JEFFERSON STREET ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 SAVE-A-LOT #489 1616 MILL SQUARE ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #726 2643 HWY 280 W ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WINN DIXIE #456 1061 U.S. HWY. 280 EAST ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 ALEXANDRIA FOODLAND 85 BIG VALLEY DRIVE ALEXANDRIA ALABAMA 36250 FOOD FARE 517 5TH ST NW ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 PIGGLY WIGGLY #102 101 MEMORIAL PKWY E ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 BURTON'S FOOD STORE 7010 7TH AVENUE ALTOONA ALABAMA 35952 CORNER MARKET/PIGGLY WIGGLY 13759 BROOKLYN ROAD ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 COST PLUS #774 305 EAST THREE NOTCH STREET ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 PIC N SAV #776 550 W BYPASS ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #1091 1991 MARTIN LUTHER KING PKWY ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WINN DIXIE