Break the Game: a Practice-Based Study of Breaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018

EDM (Dance Music): Disco, Techno, House, Raves… ANTHRO 106 2018 Rebellion, genre, drugs, freedom, unity, sex, technology, place, community …………………. Disco • Disco marked the dawn of dance-based popular music. • Growing out of the increasingly groove-oriented sound of early '70s and funk, disco emphasized the beat above anything else, even the singer and the song. • Disco was named after discotheques, clubs that played nothing but music for dancing. • Most of the discotheques were gay clubs in New York • The seventies witnessed the flowering of gay clubbing, especially in New York. For the gay community in this decade, clubbing became 'a religion, a release, a way of life'. The camp, glam impulses behind the upsurge in gay clubbing influenced the image of disco in the mid-Seventies so much that it was often perceived as the preserve of three constituencies - blacks, gays and working-class women - all of whom were even less well represented in the upper echelons of rock criticism than they were in society at large. • Before the word disco existed, the phrase discotheque records was used to denote music played in New York private rent or after hours parties like the Loft and Better Days. The records played there were a mixture of funk, soul and European imports. These "proto disco" records are the same kind of records that were played by Kool Herc on the early hip hop scene. - STARS and CLUBS • Larry Levan was the first DJ-star and stands at the crossroads of disco, house and garage. He was the legendary DJ who for more than 10 years held court at the New York night club Paradise Garage. -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

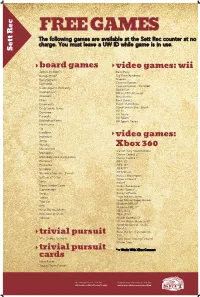

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Chris Canfield

308 Western Ave, Flr 2 1-617-417-0006 Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected] Chris Canfield http://chriscanfield.net “Few people can walk into a department and have an immediate impact. Chris is one of those people.” - Robert Nelson, 2K Sports Qualifications: Employment History: o Ten years of professional game development experience. Designed for all previous and next-gen platforms, including Xbox Subatomic Studios 360, PS3, Wii, iPhone, iPad, PC, Web, DS, PSP, PS2, GameCube, 2010 - Present Xbox 1, and iPod Video. o Lifetime metacritic average of 84% with multiple games-of-the-year Harmonix Music Systems and an estimated 1.6 billion dollar retail gross. Inc. o Lectured about game design and production at MIT, Worcester 2004 – 2010 Polytechnic, Becker College, McGill University, College Week Online, DARPA, others. o ITT Norwood’s special consultant about game design issues. Stainless Steel Studios Inc. Taught full courses in game design at Bristol Community College, 2003 ITT Tech. o Experience designing for unique devices, including 2D and 3D VCE / Sega Sports cameras, wands, keyboards / mice, gamepads, accelerometers, 2002 Guitars, Drums, and other custom plastic. o Flash, 3DS Max, Visual C++, Unity3D, Dreamweaver, Photoshop, and most major development tools for the PC, 360, and PS3. Education: Masters Professional Roles: Digital Media Northeastern University Senior Designer / Systems Designer / Level Design: 2012 Fieldrunners 2, Guitar Hero II, Dance Central, Rock Band 1, Eyetoy Antigrav, Karaoke Revolution Party, Tinkerbox Bachelor Crafted design vision for the critically acclaimed Guitar Hero 2. Sociology Additionally, spearheaded content implementation teams, defined design University of California, departmental processes, created major gameplay subsystems, laid out Irvine shell flows and usability languages, built discrete sections of level 2001 design, and wrote style bibles. -

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Sony Sells US-Based Online Game Unit 3 February 2015

Sony sells US-based online game unit 3 February 2015 including its laptop business and Manhattan headquarters, in a bid to claw back to steady profitability after years of massive losses. Founded in 2000, New York-based Columbus Nova manages more than $15 billion in assets, through its own funds and affiliated portfolio companies, according to the statement from the company. In 2010, it bought Harmonix Music Systems, maker of Rock Band and Dance Central, from Viacom. © 2015 AFP Fans play games at Sony booth during the annual E3 video game extravaganza in Los Angeles, California, on June 10, 2014 Japan's Sony has sold its online gaming unit to a US investment firm, in a move that should free it to make titles for consoles other than PlaySation. New York investment management firm Columbus Nova has acquired Sony Online Entertainment (SOE), maker of the popular 3D fantasy multiplayer game EverQuest, the companies said in a statement on Monday. The deal—financial terms were not disclosed—will see the former Sony unit operate as an independent game development studio under the name Daybreak Game Company. Columbus Nova, based in New York, already owns the maker of the music video game Rock Band. The move will mean the renamed company can develop games for mobile devices and non-Sony consoles, such as Microsoft's Xbox, it said. EverQuest competes with the popular World Of Warcraft title. Sony has been offloading a string of assets, 1 / 2 APA citation: Sony sells US-based online game unit (2015, February 3) retrieved 27 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2015-02-sony-us-based-online-game.html This document is subject to copyright. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

A Methodology for Physical Creativity

Suit The System To The Player: A Methodology for Physical Creativity Jane Friedhoff Parsons, The New School For Design 79 Fifth Avenue, Floor 16 New York, NY 10011 +1 (212) 229 - 8908 [email protected] ABSTRACT The PS Move, Kinect, and Wii tout their technological capabilities as evidence that they can best support intuitive, creative movements. However, games for these systems tend to use their technology to hold the player to higher standards of conformity. This style of game design can result in the player being made to 'fit' the game, rather than the other way around. It is worthwhile to explore alternatives for exertion games, as they can encourage exploration of long-dormant physical creativity in adults and potentially create coliberative experiences around the transgression of social norms. This paper synthesizes a methodology including generative outputs, multiple and simultaneous forms of exertion, minimized player tracking, irreverent metaphors, and play with social norms in order to promote. Scream 'Em Up tests this methodology and provides direction for future research. Keywords game design, physical creativity, embodied play, coliberation INTRODUCTION A major trend in console design is the development of increasingly sophisticated technology for tracking physical movement. The PS Move, Kinect, Wii, and other platforms largely eschew traditional controllers, instead asking the players to move their bodies or use their voices to interact with the system. Such systems tout their technological power as a shorthand for supporting more intuitive, more natural movement. The Kinect's marketing is emblematic of this: advertisements state, “you are the controller. […] If you have to kick, then kick, if you have to jump, then jump. -

Dance Central 2!

Welcome to Dance central 2! WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360® console instructions, Kinect™ sensor manual, and any other peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement hardware manuals, GETTInG STARTED go to www.xbox.com/support or call Xbox Customer Support. • Make sure your entire body is visible in the Helper Frame at the top of the screen. If you are playing with a friend, each player appears in a Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games separate Helper Frame. Photosensitive seizures • Reach your right hand out to the side to select menu items, such as A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain CONTInUe on the title screen, and then swipe from right to left. visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition • Return to a previous screen by reaching out your left hand to select that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. BACK in the lower-left corner, and then swiping from left to right. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered © vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, • Switch to navigating the menus using your Xbox 360 controller by or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or pressing any button. to exit controller mode, press the START button. convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. -

Twelve Weeks of Dance Exergaming in Overweight and Obese Adolescent

ARTICLE IN PRESS JSHS344_proof ■ 6 December 2016 ■ 1/8 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect ScienceDirect Journal of Sport and Health Science xx (2016) 1–8 Production and hosting by Elsevier www.jshs.org.cn 1bs_bs_query Q2 Original article 2bs_bs_query 3bs_bs_query Twelve weeks of dance exergaming in overweight and obese adolescent 4bs_bs_query 5bs_bs_query girls: Transfer effects on physical activity, screen time, and self-efficacy 6bs_bs_query Q1 7bs_bs_query Amanda E. Staiano *, Robbie A. Beyl, Daniel S. Hsia, Peter T. Katzmarzyk, Robert L. Newton Jr 8bs_bs_query Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA 9bs_bs_query Received 29 June 2016; revised 3 August 2016; accepted 5 September 2016 10bs_bs_query Available online 11 bs_bs_query 12bs_bs_query Background: Given the low levels of physical activity (PA) among adolescent girls in the US, there is a need to identify tools to motivate increased 13bs_bs_query PA. Although there is limited evidence that adolescents transfer PA from one context to another, exergames (i.e., video games that require gross 14bs_bs_query motor activity) may act as a gateway to promote overall PA outside game play. The purpose of this study was to examine potential transfer effects 15bs_bs_query (i.e., influences on external behaviors and psychological constructs) of a 12-week exergaming intervention on adolescent girls’ PA, screen time, 16bs_bs_query and self-efficacy toward PA, as well as the intrinsic motivation of exergaming. ≥ 17bs_bs_query Methods: Participants were 37 girls aged 14–18 years (65% African American, 35% white) who were overweight or obese (body mass index 85th 18bs_bs_query percentile) and were recruited from the community via school, physicians, news media, and social media sites. -

Kinect + Dance Central 2 + Dance Central 3 + Kinect Adventures

wygenerowano 28/09/2021 15:31 KINECT + DANCE CENTRAL 2 + DANCE CENTRAL 3 + KINECT ADVENTURES cena 476 zł dostępność Oczekujemy platforma Xbox 360 odnośnik robson.pl/produkt,16684,kinect___dance_central_2___dance_central_3___kinec.html Adres ul.Powstańców Śląskich 106D/200 01-466 Warszawa Godziny otwarcia poniedziałek-piątek w godz. 9-17 sobota w godz. 10-15 Nr konta 25 1140 2004 0000 3702 4553 9550 Adres e-mail Oferta sklepu : [email protected] Pytania techniczne : [email protected] Nr telefonów tel. 224096600 Serwis : [email protected] tel. 224361966 Zamówienia : [email protected] Wymiana gier : [email protected] W ZESTWIE: ● SENSOR MICROSOFT KINECT ● DANCE CENTRAL 2 PL - KOD DO POBRANIA GRY ● DANCE CENTRAL 3 PL ● KINECT ADVENTURES PL Kinect Kinect to urządzenie przeznaczone do konsoli Xbox 360, pozwalające na sterowanie grami przy wykorzystaniu własnego ciała (skacząc, biegnąc w miejscu, kopiąc, rzucając, łapiąc, etc). Zostało ono wyposażone w specjalny czujnik, w skład którego wchodzi kamera, mikrofon oraz przestrzenny sensor ruchu oraz procesor. Dzięki temu możliwe jest odczytywanie ruchów gracza znajdującego się przed telewizorem i przenoszenie ich na ekran w czasie rzeczywistym. Oprócz tego w trakcie rozgrywki można wydawać rozmaite komendy (w kilku dostępnych językach) –; w ten sposób następujące interakcja z postaciami widocznymi na ekranie. Z kontrolera można skorzystać już przy logowaniu się do Xboksa 360, a także w trakcie przeglądania jej zasobów - nic nie staje na przeszkodzie temu, by uruchomić grę korzystając z komendy głosu. Dlatego też na potrzeby Kinecta została przygotowana odświeżona wersja dashboarda (interfejsu konsoli). DANCE CENTRAL 2 Dance Central 2 to kontynuacja popularnej gry tanecznej, wydanej jako jeden z tytułów startowych dla kontrolera Kinect. -

Kinect for Xbox 360

MEDIA ALERT “Kinect” for Xbox 360 sets the future in motion — no controller required Microsoft reveals new ways to play that are fun and easy for everyone Sydney, Australia – June 15th – Get ready to Kinect to fun entertainment for everyone. Microsoft Corp. today capped off a two-day world premiere in Los Angeles, complete with celebrities, stunning physical dexterity and news from a galaxy far, far away, to reveal experiences that will transform living rooms in North America, beginning November 4th and will roll out to Australia and the rest of the world thereafter. Opening with a magical Cirque du Soleil performance on Sunday night attended by Hollywood’s freshest faces, Microsoft gave the transformation of home entertainment a name: Kinect for Xbox 360. Then, kicking off the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), Xbox 360 today invited the world to dance, hurdle, soar and make furry friends for life — all through the magic of Kinect — no controller required. “With ‘Kinectimals*’ and ‘Kinect Sports*’, ‘Your Shape™: Fitness Evolved*’ and ‘Dance Central™*’, your living room will become a zoo, a stadium, a fitness room or a dance club. You will be in the centre of your entertainment, using the best controller ever made — you,” said Kudo Tsunoda, creative director for Microsoft Game Studios. Microsoft and LucasArts also announced that they will bring Star Wars® to Kinect in 2011. And, sprinkling a little fairy dust on Xbox 360, Disney will bring its magic as well. “Xbox LIVE is about making it simple to find the entertainment you want, with the friends you care about, wherever you are.