Tiktok and Short-Form Screendance Before and After Covid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

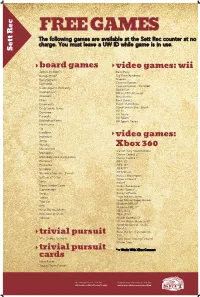

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Brochure Zap Ado Films Et Musiques

A la médiathèque Hélène Oudoux, tu peux : Le Zapping des Ados - emprunter des livres, revues, CD et DVD ; - consulter des documents sur place ; - venir travailler seul ou en groupe ; - te rendre à l’espace multimédia pour surfer sur Internet ; Vendredi 22 février 2013 - participer à des animations tout au long de l’année. _______________________________________________ Médiathèque Hélène Oudoux Danse et films musicaux Allée Albert Thomas 01.60.11.04.21 Mardi : 15h – 18h Mercredi : 10h – 18h Vendredi : 15h – 20h Samedi : 10h -18h _______________________________________________ Consultez le portail des médiathèques de Massy ! Rendez-vous sur le site de la ville http://www.ville-massy.fr La consultation des documents est libre et gratuite. Pour emprunter les documents (pendant 4 semaines), il faut être inscrit. La carte de lecteur permet d’emprunter dans les deux médiathèques. Pour les moins de 14 ans : gratuit De 14 ans à 18 ans : 3,29 € si l’on veut emprunter des CD, DVD et autres documents multimédia. Pour s’inscrire il faut : 1 justificatif de domicile de moins de 3 mois 1 pièce d’identité 1 autorisation parentale pour les moins de 18 ans Médiathèque Hélène Oudoux NOTES De la danse a n’en plus finir ! NOTES Voici une sélection de quelques fictions et documentaires sur la danse que tu peux retrouver à la médiathèque Hélène Oudoux. • La danse Bollywood • Le Hip Hop Om Shanti Om Réalisateur : Farah Khan Turn it loose : l’ultime battle Acteurs : Shilpa Shetty, Amitabh Bachchan, Salman Kahn Réalisateur : Alastair Siddons Année de production : 2008 Acteurs : Ronnie Abaldonado, Hong10, Lilou, Durée : 2h50 RoxRite, Taisuke Année de production : 2010 Durée : 1h37 Synopsis Synopsis « Dans les années 70, Om Prakash Makhija (Shah Rukh Khan) est un "junior artist", c’est à dire un figurant. -

Breaking Bboy Lego Water Flow Warsaw Challenge 2009 Kleju Hip-Hop Dance Hip-Hop International Świadomość Polssky Funk Styles Batman Muzyka, Styl, Życie

numer 2 lipiec 2009 BREAKING BBOY LEGO WATER FLOW WARSAW CHALLENGE 2009 KLEJU HIP-HOP DANCE HIP-HOP INTERNATIONAL ŚWIADOMOŚĆ POLSSKY FUNK STYLES BATMAN MUZYKA, STYL, ŻYCIE INSIDE Pierwszy numer Flava Dance FLAVA CREW Magazine odniósł niebywały 7 Breaking sukces. Nawet nasze logo Flava Dance Magazine 8 Bboy Lego - Water Flow wisi na Pałacu Kultury i Nauki! Darmowe pismo dla tancerzy Dla nas to naprawdę zaje.. 12 Warsaw Chalenge ‘09 i ludzi związanych z tańcem. sta motywacja! A to wszystko dzięki Wam! 16 Freestyle Session Europe REDAKTOR Szymon Szylak 18 bboy kleju Wasze rady pozwalają na nie- Bboy Simon ustanny rozwój naszej kultury 22 Flava Summer Jam i oczywiście pisma, dlate- SEKRETARZ go wielkie propsy dla ludzi 22 Sami Swoi Vol Bartek Biernacki 3 żyjących tańcem i czynnie Bboy Bartaz angażujących się w kulturę. 24 Hip-Hop Dance BREAKING Wpadki w pierwszym wyda- Bartaz, Rafuls, Cet, Roody niu pokazały nam właściwy 24 alias:polsSky/kbc kierunek rozwoju. Uczymy FUNK STYLES sie na błędach. Co za tym 26 HipHop International Pitzo idzie, macie świeże materiały O.C.B w Hip-Hop Dance z całego świata, pozbawione 28 HIP-HOP DANCE ankieta - świadomość błędów i nieciekawych wpa- 29 Ryfa, Ewulin dek. Materiały, dzięki którym poszerzy się nasza wspólna KONTAKTY MIĘDZYNARODOWE świadomość. 31 Funk Styles Enzo, Zyskill Wiecie co zmotywowało 32 funk - muzyka, styl , życie KOREKTA pismo do działania? To, Ryfa że wszyscy jesteśmy „podob- 34 batman ni”, a w naszych żyłach krąży OPRAWA GRAFICZNA prawdziwy Hip-Hop i najpraw- Szymon Szylak dziwszy bit. FOTOGRAFIA Nic nie odda tego jak tworzy Paweł Grzybek się historia. -

Twelve Weeks of Dance Exergaming in Overweight and Obese Adolescent

ARTICLE IN PRESS JSHS344_proof ■ 6 December 2016 ■ 1/8 HOSTED BY Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect ScienceDirect Journal of Sport and Health Science xx (2016) 1–8 Production and hosting by Elsevier www.jshs.org.cn 1bs_bs_query Q2 Original article 2bs_bs_query 3bs_bs_query Twelve weeks of dance exergaming in overweight and obese adolescent 4bs_bs_query 5bs_bs_query girls: Transfer effects on physical activity, screen time, and self-efficacy 6bs_bs_query Q1 7bs_bs_query Amanda E. Staiano *, Robbie A. Beyl, Daniel S. Hsia, Peter T. Katzmarzyk, Robert L. Newton Jr 8bs_bs_query Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA 9bs_bs_query Received 29 June 2016; revised 3 August 2016; accepted 5 September 2016 10bs_bs_query Available online 11 bs_bs_query 12bs_bs_query Background: Given the low levels of physical activity (PA) among adolescent girls in the US, there is a need to identify tools to motivate increased 13bs_bs_query PA. Although there is limited evidence that adolescents transfer PA from one context to another, exergames (i.e., video games that require gross 14bs_bs_query motor activity) may act as a gateway to promote overall PA outside game play. The purpose of this study was to examine potential transfer effects 15bs_bs_query (i.e., influences on external behaviors and psychological constructs) of a 12-week exergaming intervention on adolescent girls’ PA, screen time, 16bs_bs_query and self-efficacy toward PA, as well as the intrinsic motivation of exergaming. ≥ 17bs_bs_query Methods: Participants were 37 girls aged 14–18 years (65% African American, 35% white) who were overweight or obese (body mass index 85th 18bs_bs_query percentile) and were recruited from the community via school, physicians, news media, and social media sites. -

Kinect + Dance Central 2 + Dance Central 3 + Kinect Adventures

wygenerowano 28/09/2021 15:31 KINECT + DANCE CENTRAL 2 + DANCE CENTRAL 3 + KINECT ADVENTURES cena 476 zł dostępność Oczekujemy platforma Xbox 360 odnośnik robson.pl/produkt,16684,kinect___dance_central_2___dance_central_3___kinec.html Adres ul.Powstańców Śląskich 106D/200 01-466 Warszawa Godziny otwarcia poniedziałek-piątek w godz. 9-17 sobota w godz. 10-15 Nr konta 25 1140 2004 0000 3702 4553 9550 Adres e-mail Oferta sklepu : [email protected] Pytania techniczne : [email protected] Nr telefonów tel. 224096600 Serwis : [email protected] tel. 224361966 Zamówienia : [email protected] Wymiana gier : [email protected] W ZESTWIE: ● SENSOR MICROSOFT KINECT ● DANCE CENTRAL 2 PL - KOD DO POBRANIA GRY ● DANCE CENTRAL 3 PL ● KINECT ADVENTURES PL Kinect Kinect to urządzenie przeznaczone do konsoli Xbox 360, pozwalające na sterowanie grami przy wykorzystaniu własnego ciała (skacząc, biegnąc w miejscu, kopiąc, rzucając, łapiąc, etc). Zostało ono wyposażone w specjalny czujnik, w skład którego wchodzi kamera, mikrofon oraz przestrzenny sensor ruchu oraz procesor. Dzięki temu możliwe jest odczytywanie ruchów gracza znajdującego się przed telewizorem i przenoszenie ich na ekran w czasie rzeczywistym. Oprócz tego w trakcie rozgrywki można wydawać rozmaite komendy (w kilku dostępnych językach) –; w ten sposób następujące interakcja z postaciami widocznymi na ekranie. Z kontrolera można skorzystać już przy logowaniu się do Xboksa 360, a także w trakcie przeglądania jej zasobów - nic nie staje na przeszkodzie temu, by uruchomić grę korzystając z komendy głosu. Dlatego też na potrzeby Kinecta została przygotowana odświeżona wersja dashboarda (interfejsu konsoli). DANCE CENTRAL 2 Dance Central 2 to kontynuacja popularnej gry tanecznej, wydanej jako jeden z tytułów startowych dla kontrolera Kinect. -

Hip Hop Terms

1 Topic Page Number General Hip Hop Definitions ………………………………………………. 3 Definitions Related to Specific Dance Styles: ♦ Breaking ………………………………………………………………………. 4 ♦ House ………………………………………………………..………………… 6 ♦ Popping / Locking …………………………………………….….……… 7 2 GENERAL • Battle A competition in which dancers, usually in an open circle surrounded by their competitors, dance their routines, whether improvised (freestyle) or planned. Participants vary in numbers, ranging from one on one to battles of opposing breaking crews, or teams. Winners are determined by outside judges, often with prize money. • • Cypher Open forum, mock exhibitions. Similar to battles, but less emphasis on competition. • Freestyle Improvised Old School routine. • Hip Hop A lifestyle that is comprised of 4 elements: Breaking, MCing, DJing, and Graffiti. Footwear and clothing are part of the hip hop style. Much of it is influenced by the original breaking crews in the 1980’s from the Bronx. Sneakers are usually flat soled and may range from Nike, Adidas, Puma, or Converse. Generally caps are worn for spins, often with padding to protect the head. To optimize the fast footwork and floor moves, the baggy pants favored by hip hop rappers are not seen. o Breaking Breakdancing. o MCing Rapping. MC uses rhyming verses, pre‐written or freestyled, to introduce and praise the DJ or excite the crowd. o DJing Art of the disk jockey. o Graffiti Name for images or lettering scratched, scrawled, painted usually on buildings, trains etc. • Hip Hop dance There are two main categories of hip hop dance: Old School and New School. • New School hip hop dance Newer forms of hip hop music or dance (house, krumping, voguing, street jazz) that emerged in the 1990s • Old School hip hop dance Original forms of hip hop music or dance (breaking, popping, and locking) that evolved in the 1970s and 80s. -

Download Free Scream Usher

Download free scream usher Scream. Artist: Usher. MB · Scream. Artist: Usher. MB · Scream. Artist: Usher. MB. Usher - Scream mp3 free download for mobile. Scream (Original Mix) | Preview · Download original Kbps, Mb, Album: Master - Single (). Watch the video, get the download or listen to Usher – Scream for free. Scream appears on the album Looking 4 Myself (Deluxe Version). "Scream" peaked at #1. DOWNLOAD MP3: LATEST MUSIC NEWS: mp3 download link Usher Scream lyrics and mp3 download link. Download: SUBSCRIBE FOR MORE. Usher Scream Free Mp3 Download in high quality bit. Scream. Usher • MB • 4K plays. Looking 4 Myself (deluxe Version). Scream. Usher - Looking 4 Myself (deluxe Version) • MB • K plays. Mp3 Tags: Download Usher - Usher – 3 Where to Get Usher – Scream Free Audio Download, Free Usher – 3 Song Download, Usher. Download mp3 free usher scream Jun 4, Download This Track. Usher – Scream Lyrics. Usher, baby. Yeah, we did it again. And this time. Lyrics of SCREAM by Usher: If you want it done right, Hope you're ready to go all night, Get you going like Ah-Ooh-Baby- Baby-Ooh-Baby-Baby. Big collection of usher - scream ringtones for phone and tablet. All high quality mobile ringtones are available for free download. Stream Scream by Usher Raymond Music from desktop or your mobile device. Stream Usher - Scream (R3hab Remix) by R3HAB from desktop or your mobile device. FREE SONGS at BITCH, DOWNLOAD USHER NEW TRACK. Buy Scream: Read 69 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of millions more songs. -

A Street Dance Toolkit

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Master's Theses Student Research 12-8-2020 FROM CONCRETE TO THE CLASSROOM: A STREET DANCE TOOLKIT Tarayjah Hoey-Gordon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses Recommended Citation Hoey-Gordon, Tarayjah, "FROM CONCRETE TO THE CLASSROOM: A STREET DANCE TOOLKIT" (2020). Master's Theses. 182. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/theses/182 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2020 TARAYJAH HOEY-GORDON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School FROM CONCRETE TO THE CLASSROOM: A STREET DANCE TOOLKIT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Arts Tarayjah Hoey-Gordon College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Theatre Arts and Dance Dance Education December 2020 This Thesis by: Tarayjah Hoey-Gordon Entitled: From Concrete to the Classroom: A Street Dance Toolkit has been approved as meeting the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Theatre Arts and Dance, Program of Dance Education Accepted by the Thesis Committee: _______________________________________________________ Christy O’Connell-Black, M.A., Chair, Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra L. Minton, Ph.D., Committee Member Accepted by the Graduate School: __________________________________________________________ Jeri-Anne Lyons, Ph.D.