The Dream of Joseph: Practices of Identity in Pacific Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exhibitions & Events at Auckland Art Gallery Toi O

Below: Michael Illingworth, Man and woman fi gures with still life and fl owers, 1971, oil on canvas, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki MARITIME MUSEUM FERRY TERMINAL QUAY ST BRITOMART On Show STATION EXHIBITIONS & EVENTS CUSTOMS ST BEACH RD AT AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TĀMAKI FEBRUARY / MARCH / APRIL 2008 // FREE // www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ANZAC AVE SHORTLAND ST HOBSON ST HOBSON ALBERT ST ALBERT QUEEN ST HIGH ST PRINCES ST PRINCES BOWEN AVE VICTORIA ST WEST ST KITCHENER LORNE ST LORNE ALBERT PARK NEW MAIN WELLESLEY ST WEST STANLEY ST GALLERY GALLERY GRAFTON RD WELLESLEY ST AUCKLAND AOTEA R MUSEUM D SQUARE L A R O Y A M Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Discount parking - $4 all day, weekends and PO Box 5449, Auckland 1141 public holidays, Victoria St carpark, cnr Kitchener New Gallery: Cnr Wellesley and Lorne Sts and Victoria Sts. After parking, collect a discount voucher from the gallery Open daily 10am to 5pm except Christmas Day and Easter Friday. Free guided tours 2pm daily For bus, train and ferry info phone MAXX Free entry. Admission charges apply for on (09) 366 6400 or go to www.maxx.co.nz special exhibitions The Link bus makes a central city loop Ph 09 307 7700 Infoline 09 379 1349 www.stagecoach.co.nz/thelink www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ARTG-0009-serial Auckland Art Gallery’s main gallery will be closing for development on Friday 29 February. Exhibitions and events will continue at the New Gallery across the road, cnr Wellesley & Lorne sts. On Show Edited by Isabel Haarhaus Designed by Inhouse ISSN 1177-4614 Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki relies on From the Chris Saines, the good will and generosity of corporate Gallery Floor Plans partners. -

Art History Sources at the Hocken Collections

Reference Guide Art History Sources at the Hocken Collections Sir William Fox, 1812-93. W Fox’s House, Nelson. 1848. Watercolour on paper: 238 x 345mm. Accession No.: 4,274 31. Hocken Collections/Te Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago Library Nau Mai Haere Mai ki Te Uare Taoka o Hākena: Welcome to the Hocken Collections He mihi nui tēnei ki a koutou kā uri o kā hau e whā arā, kā mātāwaka o te motu, o te ao whānui hoki. Nau mai, haere mai ki te taumata. As you arrive We seek to preserve all the taoka we hold for future generations. So that all taoka are properly protected, we ask that you: place your bags (including computer bags and sleeves) in the lockers provided leave all food and drink including water bottles in the lockers (we have a researcher lounge off the foyer which everyone is welcome to use) bring any materials you need for research and some ID in with you sign the Readers’ Register each day enquire at the reference desk first if you wish to take digital photographs Beginning your research This guide gives examples of the types of material relating to New Zealand art history held in the collections. All items must be used within the library. As the collection is large and constantly growing not every item is listed here, but you can search for other material on our Online Public Access Catalogues: for books, theses, journals, magazines, newspapers, maps, and audiovisual material, use Library Search|Ketu. The advanced search ‐ https://goo.gl/HVNTqH gives you several search options, and you can refine your results to the Hocken Library on the left side of the screen. -

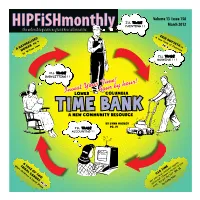

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12. -

13 1 a R T + O B Je C T 20 18

NEW A RT + O B J E C T COLLECTORS ART + OBJECT 131 ART 2018 TWENTIETH CENTURY DESIGN & STUDIO CERAMICS 24 –25 JULY AO1281FA Cat 131 cover.indd 1 10/07/18 3:01 PM 1 THE LES AND AUCTION MILLY PARIS HIGHLIGHTS COLLECTION 28 JUNE PART 2 Part II of the Paris Collection realised a sale The record price for a Tony Fomison was total of $2 000 000 and witnessed high also bettered by nearly $200 000 when clearance rates and close to 100% sales by Ah South Island, Your Music Remembers value, with strength displayed throughout Me made $321 000 hammer ($385 585) the lower, mid and top end of the market. against an estimate of $180 000 – The previous record price for a Philip $250 000. Illustrated above left: Clairmont was more than quadrupled Tony Fomison Ah South Island, Your Music when his magnificent Scarred Couch II Remembers Me was hammered down for $276 000 oil on hessian laid onto board ($331 530) against an estimate of 760 x 1200mm $160 000 – $240 000. A new record price realised for the artist at auction: $385 585 2 Colin McCahon Philip Clairmont A new record price Scarred Couch II realised for the artist North Shore Landscape at auction: oil on canvas, 1954 mixed media 563 x 462mm and collage on $331 530 unstretched jute Milan Mrkusich Price realised: $156 155 1755 x 2270mm Painting No. II (Trees) oil on board, 1959 857 x 596mm Price realised: $90 090 John Tole Gordon Walters Timber Mill near Rotorua Blue Centre oil on board PVA and acrylic on 445 x 535mm Ralph Hotere canvas, 1970 A new record price realised Black Window: Towards Aramoana 458 x 458mm for the artist at auction: acrylic on board in colonial sash Price realised: $73 270 $37 235 window frame 1130 x 915mm Price realised: $168 165 Peter Peryer A new record price realised Jam Rolls, Neenish Tarts, Doughnuts for the artist at auction: gelatin silver print, three parts, 1983 $21 620 255 x 380mm: each print 3 RARE BOOKS, 22 AUG MANUSCRIPTS, George O’Brien Otago Harbour from Waverley DOCUMENTS A large watercolour of Otago Harbour from Waverley. -

Spring Catalogue 2012

Spring Catalogue 2012 pierre peeters gallery 251 Parnell Road: Habitat Courtyard: Auckland: [email protected] (09)3774832 Welcome to our 2012 Spring Catalogue. Pierre Peeters Gallery presents fine examples of New Zealand paintings, works on paper and sculpture which span from the nineteenth century to the present day. For all enquiries ph (09)377 4832 or contact us at [email protected] www.ppg.net.nz Cover illustration: Len Lye, Self Portrait with Night Tree: 1947 W .S Melvin circa 1880 Wet Jacket Arm: Milford Sound Initialled Lower right ‘WSM’ Oil on opaque glass 170 x 280 mm W. S Melvin circa 1880 Lake Manapouri Initialled Lower left ‘ WSM’ Oil on opaque glass 170 x 280 mm These two works by W.S Melvin exemplify the decorative landscape painting of nineteenth century painters of the period working in New Zealand. They knowingly utilise the decorative strength of adjacent reds , soft purples and greens . Painted on what was commonly called ‘milk glass’, popular in nineteenth century applied arts, here Melvin employs this luminous medium for his deftly realised depictions of the picturesque South Island. W.S. Melvin was a nineteenth century painter who exhibited with the Otago Art Society from 1887–1913; and whose work featured in the NZ and South Seas Exhibition in Dunedin 1889–90. John Barr Clarke Hoyte (1835-1913) Coastal Inlet c.1870 Watercolour 390 x 640 mm John Barr Clarke Hoyte could produce airy, sweeping views of the picturesque, but in works like this, he combines the atmosphere and dampness of the elements of a North Island inlet, with a homely, pragmatic and altogether, endearing aspect. -

Donald Heald Rare Books a Selection of Fine Books and Manuscripts

Donald Heald Rare Books A Selection of Fine Books and Manuscripts Donald Heald Rare Books A Selection of Fine Books and Manuscripts Donald Heald Rare Books 124 East 74 Street New York, New York 10021 T: 212 · 744 · 3505 F: 212 · 628 · 7847 [email protected] www.donaldheald.com Americana: Items 1 - 27 Travel: Items 28 - 50 Color Plate & Illustrated: Items 51 - 71 Natural History: Items 72 - 95 Miscellany: Items 96 - 100 All purchases are subject to availability. All items are guaranteed as described. Any purchase may be returned for a full refund within ten working days as long as it is returned in the same condition and is packed and shipped correctly. The appropriate sales tax will be added for New York State residents. Payment via U.S. check drawn on a U.S. bank made payable to Donald A. Heald, wire transfer, bank draft, Paypal or by Visa, Mastercard, American Express or Discover cards. AMERICANA 1 BLASKOWITZ, Charles (ca. 1743-1823). A Topographical Chart of the Bay of Narraganset in the Province of New England with all the Isles contained therein, among which Rhode Island and Connonicut [sic] have been particularly surveyed ... To which has been added the Several works and batteries raised by the Americans ... London: William Faden, 22 July 1777. Engraved map, dissected into 16 sections at a contemporary date, linen-backing renewed (expert restoration at the corners). Sheet size: 37 x 25 1/8 inches. Rare first edition of Blaskowitz’s famed Revolutionary War map of Narragansett Bay published by Faden. Charles Blaskowitz arrived in America in the early 1760s as a young but evidently skilled surveyor and began work in upstate New York and along the St. -

Mark Bentley Adams CV 2015

Mark Bentley Adams C V 2015 b.1949: Christchurch: Te Wai Pounamu Aotearoa New Zealand phone/fax: 00 64 9 379 7501 mobile: 00 64 021 036 7447 phone: 00 64 3 312 1271 [email protected] PO Box 68896 Newton Auckland New Zealand 173 High St Oxford Te Wai Pounamu 7430 Professional Qualifications 1969 DFA, University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts Professional Experience 1982-88 Sharp Black and White Photographic Partnership 1982-88 Real Pictures Photographic Gallery and Laboratory 1996 - Studio La Gonda Photographic Partnership Teaching Experience 1996- 1999 Elam School of Fine Arts, Department of Photography, 1994- 1996 Auckland Institute of Technology, Department of Photography 1991- 1993 Carrington Polytechnic School of Design, Department of Photography 1990- 1992 ASA School of Fine Arts Selected Shows 2015 Clevedon Garden 1978. Hori Paraone / George Brown Paul McNamara Gallery. Whanganui 2015 Nine Fathom Passage. Dusky Sound. Two Rooms Gallery Auckland 2015 'Sign Here'. Sites where the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 Mangere Arts Centre nga tohu o uenuku Curated by Hannah Scott 2014 'Mark Adams. Tatau: Photographs from the Tatau project 1978 - 2005'. Ilam Campus Gallery. School of Fine Arts University of Canterbury 2014 'Cook's Sites' Curated by Peter Vangioni. Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetu 2013 'A Portrait of the Artist Tony Fomison', Chamber Gallery, Rangiora 2013 'Archives'. Photographs by Mark Adams, Two Rooms Gallery, Auckland 2012 Mark Adams Photographs: McNamara Gallery Whanganui 2010 'Lava. Photographs from Polynesia'. 2 Rooms Gallery, Auckland 2010 'Tatau'. University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Curated by Nicholas Thomas 2009 'Tene Waitere's travels'. -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Gallery Calendar (Subject to Adjustment)

CDA No. Forty-three 1972 President: Miles Warren The Journal of the Canterbury Society of Arts Secretary Manager: Russell Laidlaw 66 Gloucester Street Telephone 67-261 Exhibitions Officer: Tony Geddes P.O. Box 772 Christchurch Receptionist: Joanna Mowat Registered et the Post Office Headquarters, Wellington as a magazine. News Editor: S. McMillan gallery calendar (subject to adjustment) May 5 - 19 N. Z. Institute of Architects. April — May 15 British Painting. May 18 — June 1 Keith Reed and John Parker. Paintings. May 17 — June 2 Phil Clairmont. Paintings & Drawings. May 20 — June 6 Quentin MacFarlane. Paintings. June 7 — June 28 Benson and Hedges Art Award. June 4 — 16 J. V. Moore (post-humous). Paintings. June 9 — 25 Michael Eaton. Paintings. June 19 - 30 H. Struyk. Painting. July 4 — July 19 Graphic and Craft. Receiving day June 26. (continued overleaf) LUNCHTIME CONCERT On May 3 at 12.10 p.m. the University Singers will give a performance in the Gallery. Tony Fomison. Oil. But there's nothing wrong with me. Purchased by the C. S. A. for the permanent collection. Photo. Orly. calendar continued July. Graphic and Craft. Joanna Paul. Alan Clark and Barry November. Town & Country. Doris Holland. The Group. \2/ Sharplin. John Coley. Rosemary Muller. Technical Institute Graphic & Design. Contemporary August. Louise Lewis. Star Secondary School. Olivia December. Helen Rockel. Junior Art Class. Open Exhibi Spencer-Bower. Louise Henderson. Tony Geddes and tion. Jewellery Jonathon Mane. V. Jamieson. September. Neuman & Grant. Annual Spring Exhibition. Exhibitions are mounted with the assistance of Guenter Taemmler October. Valerie Heinz. Paree Romanides. J. Harris. -

Teachers' Resource

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE MICHELANGELO’S DREAM 18 FEBRUARY – 16 MAY 2010 CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION 2: UNDERSTANDING THE DREAM 3: MY SOUL TO MESSER TOMMASO 4: DRAWN IN DREAMS 5: MICHELANGELO’S POETRY 6: MICHELANGELO AND MUSIC 7: REGARDÉ: SONNETS IN MICHELANGELO’S AGE 8: IMAGE CD The Teachers’ Resources are intended for use by secondary schools, colleges and teachers of all subjects for their own research. Each essay is marked with suggested links to subject areas and key stage levels. We hope teachers and educators will use these resources to plan lessons, help organise visits to the gallery or gain further insight into the exhibitions at The Courtauld Gallery. FOR EACH ESSAY CURRICULUM LINKS ARE MARKED IN RED. Cover image and right: Michelangelo Buonarroti The Dream (Il Sogno) To book a visit to the gallery or to discuss c.1533 (detail) any of the education projects at Black chalk on laid paper The Courtauld please contact: Unless otherwise stated all images [email protected] © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, 0207 848 1058 The Courtauld Gallery, London WELCOME The Courtauld Institute of Art runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. The Teachers’ Resources and Image CDs have proved immensely popular in their first year; my thanks go to all those who have contributed to this success and to those who have given us valuable feedback. -

Redressing Theo Schoon's Absence from New Zealand Art History

DOUBLE VISION: REDRESSING THEO SCHOON'S ABSENCE FROM NEW ZEALAND ART HISTORY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History in the University of Canterbury by ANDREW PAUL WOOD University of Canterbury 2003 CONTENTS Abstract .......................................... ii Acknowledgments ................................. iii Chapter 1: The Enigma of Theo Schoon .......................... 1 Chapter2: Schoon's Early Life in South-East Asia 1915-1927 ....... .17 Chapter 3: Schoon in Europe 1927-1935 ......................... 25 Chapter4: Return to the Dutch East-Indies: The Bandung Period 1936-1939 ...................... .46 Chapter 5: The First Decade in New Zealand 1939-1949 ............ 63 Chapter 6: The 1950s-1960s and the Legacy ......................91 Chapter 7: Conclusion ...................................... 111 List of Illustrations ................................ 116 Appendix 1 Selective List of Articles Published on Maori Rock Art 1947- 1949 ...................................... 141 Appendix 2 The Life of Theo Schoon: A Chronology ................................... .142 Bibliography ..................................... 146 ABSTRACT The thesis will examine the apparent absence of the artist Theo Schoon (Java 1915- Sydney 1985) from the accepted canon ofNew Zealand art history, despite his relationship with some of its most notable artists, including Colin McCahon, Rita Angus and Gordon Walters. The thesis will also readdress Schoon's importance to the development of modernist art in New Zealand and Australia, through a detailed examination of his life, his development as an artist (with particular attention to his life in the Dutch East-Indies, and his training in Rotterdam, Netherlands), and his influence over New Zealand's artistic community. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgment and thanks are due the following: My thesis supervisor Jonathan Mane-Wheoke, without whose breadth of knowledge and practical wisdom, this thesis would not have been possible.