Excerpted From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Cary Cordova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO Committee: Steven D. Hoelscher, Co-Supervisor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Co-Supervisor Janet Davis David Montejano Deborah Paredez Shirley Thompson THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO by Cary Cordova, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my parents, Jennifer Feeley and Solomon Cordova, and to our beloved San Francisco family of “beatnik” and “avant-garde” friends, Nancy Eichler, Ed and Anna Everett, Ellen Kernigan, and José Ramón Lerma. Acknowledgements For as long as I can remember, my most meaningful encounters with history emerged from first-hand accounts – autobiographies, diaries, articles, oral histories, scratchy recordings, and scraps of paper. This dissertation is a product of my encounters with many people, who made history a constant presence in my life. I am grateful to an expansive community of people who have assisted me with this project. This dissertation would not have been possible without the many people who sat down with me for countless hours to record their oral histories: Cesar Ascarrunz, Francisco Camplis, Luis Cervantes, Susan Cervantes, Maruja Cid, Carlos Cordova, Daniel del Solar, Martha Estrella, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Yolanda Garfias Woo, Amelia “Mia” Galaviz de Gonzalez, Juan Gonzales, José Ramón Lerma, Andres Lopez, Yolanda Lopez, Carlos Loarca, Alejandro Murguía, Michael Nolan, Patricia Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, Nina Serrano, and René Yañez. -

Pat Adams Selected Solo Exhibitions

PAT ADAMS Born: Stockton, California, July 8, 1928 Resides: Bennington, Vermont Education: 1949 University of California, Berkeley, BA, Painting, Phi Beta Kappa, Delta Epsilon 1945 California College of Arts and Crafts, summer session (Otis Oldfield and Lewis Miljarik) 1946 College of Pacific, summer session (Chiura Obata) 1948 Art Institute of Chicago, summer session (John Fabian and Elizabeth McKinnon) 1950 Brooklyn Museum Art School, summer session (Max Beckmann, Reuben Tam, John Ferren) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont 2011 National Association of Women Artists, New York 2008 Zabriskie Gallery, New York 2005 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, 50th Anniversary Exhibition: 1954-2004 2004 Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont 2003 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, exhibited biennially since 1956 2001 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, Monotypes, exhibited in 1999, 1994, 1993 1999 Amy E. Tarrant Gallery, Flyn Performing Arts Center, Burlington, Vermont 1994 Jaffe/Friede/Strauss Gallery, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 1989 Anne Weber Gallery, Georgetown, Maine 1988 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Retrospective: 1968-1988 1988 Addison/Ripley Gallery, Washington, D.C. 1988 New York Academy of Sciences, New York 1988 American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C. 1986 Haggin Museum, Stockton, California 1986 University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 1983 Image Gallery, Stockbridge, Massachusetts 1982 Columbia Museum of Art, University of South Carolina, Columbia, -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Sobriety First, Housing Plus Meet the Man Who Runs a Homeless Program with a 93 Percent Success Rate and Why He Says Even He Couldn’T Solve San Francisco’S Crisis

Good food and drink Travel tips The Tablehopper says get ready for hops Bay Area cannabis tours p.18 at Fort Mason p.10 Visiting Cavallo Point — Susan Dyer Reynolds’s favorite things p.11 The Lodge at the Golden Anthony Torres scopes out Madrone Art Bar p.12 Gate p.19 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 34TH YEAR VOLUME 34 ISSUE 09 SEPTEMBER 2018 Reynolds Rap Sobriety first, housing plus Meet the man who runs a homeless program with a 93 percent success rate and why he says even he couldn’t solve San Francisco’s crisis BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS Detail of Gillian Ayres, 1948, The Walmer Castle pub near Camberwell School of Art, with Gillian Ayres (center) hris megison has worked with the home- and Henry Mundy (to the right of Ayres). PHOTO: COURTESY OF GILLIAN AYRES less for nearly three decades. He and his wife, Tammy, helped thousands of men get off the Cstreets, find employment, and earn their way back into Book review: ‘Modernists and Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, society. But it was a volunteer stint at a winter emergency shelter for families where they saw mothers and babies Hockney and The London Painters,’ by Martin Gayford sleeping on the floor that gave them the vision for their organization Solutions for Change. The plan was far from BY SHARON ANDERSON tionships — artists as friends, as photographs and artworks, Gayford traditional: Shelter beds, feeding programs, and conven- students and teachers, and as par- draws on extensive interviews with tional human services were replaced with a hybrid model artin gayford’s latest ticipants who combined to define artists to build an intimate history of where parents worked, paid rent, and attended onsite book takes on the history painting from Soho bohemia in the an era. -

Curriculum Vitae

38 Walker Street New York, NY 10013 tel: 212-564-8480 www.georgeadamsgallery.com LUIS CRUZ AZACETA BORN: Havana, Cuba, 1942. Emigrated to the US 1960; US Citizenship 1967. LIVES: New Orleans, LA. EDUCATION: School of Visual Arts, New York, 1969. GRANTS AND AWARDS: Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, 2009. Penny McCall Foundation Award, 1991-92. Mid-Atlantic Grant for special projects, 1989. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Grant, New York, 1985. New York Foundation for the Arts, 1985. Mira! Canadian Club Hispanic Award, 1984. Creative Artistic Public Service (CAPS), New York, 1981-82. National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., 1980-81, 1985, 1991-92. Cintas Foundation, Institute of International Education, New York, 1972-72, 1975-76. SOLO EXHIBITIONS: “Personal Velocity in the Age of Covid,” Lyle O. Rietzel, Santo Dominigo, DR, 2020-21. “Personal Velocity: 40 Years of Painting,” George Adams Gallery, New York, NY, 2020. “Between the Lines,” Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA, 2019. “Luis Cruz Azaceta, 1984-1989,” George Adams Gallery, New York, NY, 2018. “Luis Cruz Azaceta: A Question of Color,” Lyle O. Reitzel, Santo Domingo, DR, 2018. “On The Brink,” Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA, 2017. “Luis Cruz Azaceta Swimming to Havana,” Lyle O. Reitzel, New York, NY, 2016-17. “Luis Cruz Azaceta: Dictators, Terrorism, War and Exiles,” American Museum of the Cuban Diaspora, Miami, FL, 2016. “Luis Cruz Azaceta: War & Other Disasters,” Abroms-Engel Institute for Visual Arts, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL, 2016. “State of Fear,” Pan American Art Projects, Miami, FL, 2015.* “PaintingOutLoud,” Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA, 2014.* “Dictators, Terrorism, Wars & Exile,” Aljira: A Center for Contemporary Art, Newark, NJ, 2014.* “Louisiana Mon Amour,” Acadiana Center for the Arts, Lafayette, LA, 2013.* “Falling Sky,” Lyle O. -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

Christine Giles Bill Bob and Bill.Pdf

William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley A Window on History, by George. 1993 pastel, Conte crayon, charcoal, graphite and acrylic on canvas 1 61 /2 x 87 '12 inches Courtesy of John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, California Photograph by Cesar Rubio / r.- .. 12 -.'. Christine Giles and Hatherine Plake Hough ccentricity, individualism and nonconformity have been central to San Fran cisco Bay Area and Northern California's spirit since the Gold Rush era. Town Enames like Rough and Ready, Whiskey Flats and "Pair of Dice" (later changed to Paradise) testify to the raw humor and outsider self-image rooted in Northern California culture. This exhibition focuses on three artists' exploration of a different western frontier-that of individual creativity and collaboration. It brings together paintings, sculptures, assemblages and works on paper created individually and collabora tively by three close friends: William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley. ·n, Bob and Bill William Allan, the eldest, was born in Everett, Washington, in 1936, followed by Wiley, born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937 and Hudson, born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1938. Their families eventually settled in Richland, in southeast Washington, where the three met and began a life-long social and professional relationship. Richland was the site of one of the nation's first plutonium production plants-Hanford Atomic Works. 1 Hudson remembers Richland as a plutonium boom town: the city's population seemed to swell overnight from a few thousand to over 30,000. Most of the transient population lived in fourteen square blocks filled with trailer courts. -

“Rewriting History: Artistic Collaboration Since 1960.” in Cynthia Jafee Mccabe

“Rewriting History: Artistic Collaboration Since 1960.” In Cynthia Jafee McCabe. Artistic Collaboration in the Twentieth Century. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984; pp. 64-87. Text © Smithsonian Institution. Used with permission. accords with a desire to see human beings change world history as attrition rather than as a whim, and we are more order. When we see a subscriber to the great person theory and more attuned to how large numbers of people in the present, such as Barbara Tuchman, we are all participate in world events rather than how the few are intrigued, I think, because we so desperately want to believe motivated and affected. Napoleon is beginning to appear that individuals do control the world and that history is not more the creation of the people, the nexus of their desires, mindless attrition, some effect caused by innumerable than a willful individual: he may act but he is also very people unsuspectingly reacting to a sequence of events. We definitely acted upon. like logic and the force of human emotions, and we want to Even though historians have generally accepted social be convinced that Napoleon was important, because, history as a legitimate approach and are finding it a fruitful lurking under that conviction, is the assumption that if he means for sifting through past events, art historians have can initiate world events, then, perhaps, we too can have an been reticent to give up their beliefs in individual genius. effect, t1owever small, on the world around us. For all intents and purposes, art history is still locked into The great person theory has enjoyed a wide following, the great person theory, whict1 is more appropriate to the but this approach is historically rooted in the Romantic Romantic era and the nineteenth century than the Post period. -

Calder and Abstraction April 8, 2014

Calder and Abstraction April 8, 2014 4:00–5:00 Registration Ahmanson Building, Level 2 Sign-In LAUSD Salary Point & University Credit • Ahmanson Building, Level 2 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 5:00–5:50 Lecture Calder and Abstraction • Lauren Bergman • Bing Theater ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 6:00–6:50 Exhibition in Focus Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic • Resnick Pavilion Art Workshops Shaping Space • Grades K–2 • Peggy Hasegawa • Plaza Studio** Contour Constructs • Grades K–5 • Brooke Sauer • Pavilion for Japanese Art Lobby* Paper Sculptures • Grades SPED K–5 • Judy Blake • Bing Theater Lobby* Motion Machines • Grades 6–12 • Jia Gu • Art + Technology Lab, Bing Center, Level 1* Gallery Activity Monumental Artworks • Grades 6–12 • Brandy Vause • Resnick Pavilion* Dance Workshop Balance and Motion • Shana Habel • Bing Theater ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7:00–7:25 Reception Dinner catered by The Patina Group • BP Grand Entrance ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 7:30–8:20 Exhibition in Focus Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic • Resnick Pavilion Art Workshops Shaping Space • Grades K–2 • Peggy Hasegawa • Plaza Studio** -

Abstract and Figurative: Highlights of Bay Area Painting January 8 – February 28, 2009 John Berggruen Gallery Is Pleased to Pr

Abstract and Figurative: Highlights of Bay Area Painting January 8 – February 28, 2009 John Berggruen Gallery is pleased to present Abstract and Figurative: Highlights of Bay Area Painting, a survey of historical works celebrating the iconic art of the Bay Area Figurative movement. The exhibition will occupy two floors of gallery space and will include work by artists Elmer Bischoff, Theophilus Brown, Richard Diebenkorn, Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliveira, David Park, Wayne Thiebaud, James Weeks, and Paul Wonner. Abstract and Figurative is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue with an introduction by art historian and Director of the Palm Springs Art Museum and former Associate Director and Chief Curator of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Steven A. Nash. Many of the works included in Abstract and Figurative are on loan from museums and private collections and have rarely been exhibited to the public. John Berggruen Gallery is proud to have this opportunity to bring these paintings together in commemoration of the creative accomplishments of such distinguished artists. Please join us for our opening reception on Thursday, January 8, 2009 between 5:30 and 7:30 pm. Nash writes, “There is no more fabled chapter in the history of California Art than the audacious stand made by Bay Area Figurative painters against Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s.” This regionalized movement away from the canon of the New York School (as championed by artists Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, and critic Clement Greenberg, among others) finds its roots in 1949, when a young painter by the name of David Park “gathered up all his abstract- expressionist canvases and, in an act that has gone down in local legend, drove to the Berkeley city dump and destroyed them.”1 Disillusioned with the strict non-representational tenets of a movement that promoted the Greenbergian notion of “purity” in art towards a perpetually evolving abstraction, Park submitted Kids on Bikes (1950), a small figurative painting, to a 1951 competitive exhibition and won. -

Hour by Hour!

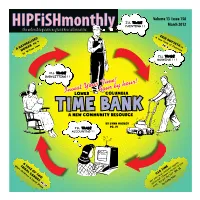

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com