The Logic of British Forest Policy, 1919-1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Plot at Torran Farm

Development Plot at Torran Farm Ford, Lochgilphead, Argyll and Bute bellingram.co.uk An opportunity to acquire an easily accessible development plot extending to approximately 1 acre (0.40ha), situated in an enviable elevated position enjoying superb panoramic views across Loch Awe • Prime development plot • Close proximity to Loch Awe • Open panoramic views • Commuting distance from • Extending to approximately 1 Oban and Lochgilphead acre • Planning permission in • Services close by for principle connection • Shared private track Lochgilphead 14 miles - Oban 32 miles – Glasgow 100 miles Description Easily accessible and extending to approximately 1 acre (0.40ha), the site is situated in an enviable elevated position and enjoys superb panoramic views to the south and east across Loch Awe. The plot is offered for sale with outline planning consent and services close by for connection. The plot offers buyers an opportunity to develop a prime residential property in an idyllic and much sought- after setting. Access to the land is from a shared private track which leads up to the plot from the single-track road. Full details of the planning permission can be found within the planning section of the the Argyll and Bute council website, under reference 18/02459/PPP, or by request through sole selling agents. Location The development plot at Torran Farm is situated on the outskirts of the small settlement of Ford, located at the southern end of Loch Awe. Loch Awe is one of Scotland’s largest and most picturesque freshwater lochs with its wooded shores, ruined castle of Kilchurn and scattered small islands. It attracts numerous visitors to the area, renowned for its salmon and trout fishing, as well as enticing climbers and walkers drawn to the Cruachan and Ben Lui mountain ranges. -

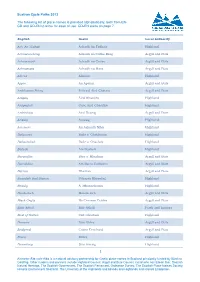

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

About Your Organisation

Section 1 - About your organisation General Contact Details for Your Organisation 1.1 Name of Community Body (CB) (or unincorporated association if applying under the Sponsored Sale of Surplus Land) Dalavich Improvement Group Full I address for nisation Address c/o Dalavich Post Office Dalavich Taynuilt Oban Postcode PA351HN Fax E-mail ( Position held in Chair if different from the nisation address Address Postcode Tele hone ( Address As main contact Postcode Tel one 3 you undertake. 100 word maximum. DIG's purposes are to: • manage community land and associated assets to benefit the community and the public • provide, or assist in providing, recreational facilities for members of the community and the public • advance community development, including rural regeneration • advance environmental protection/improvement including preservation, sustainable development and conservation of the natural environment. DIG manages: • Dalavich Community Centre • an area of Loch Awe foreshore • a playing field • income on behalf of the community and supports • a Social Club with bar and seasonal restaurant • a gardening club • an arts and crafts club. 1.5 What type of organisation are you? Description Documents to be enclosed Company Limited by Memorandum and Articles of Guarantee (required under Association community Acquisition) Certificate of Incorporation Yes - please tick Unincorporated Association Constitution / Set of Rules Yes - insert date established ~ ......~~~~ ...~~~~~ If yes, please give your registered Inland SC032664 Revenue Charity Number and provide a copy of r letter or 4 1.10 Please tell us about your community. We need you to describe your community to allow us to decide whether you have demonstrated community support for the application (see Criteria 3, p14). -

For Enquiries on This Agenda Please Contact

MINUTES of MEETING of OBAN LORN & THE ISLES COMMUNITY PLANNING GROUP held in the CORRAN HALLS, OBAN on WEDNESDAY, 13 FEBRUARY 2019 Present: Margaret Adams, Ardchattan Community Council (Chair) Councillor Elaine Robertson Melissa Stewart, Area Governance Officer, Argyll & Bute Council Samantha Somers, Community Planning Officer, Argyll & Bute Council Laura MacDonald, Community Development Officer John Sweeney, Scottish Fire and Rescue Alison Hardman, Health and Social Care Partnership Mark Stephen, Police Scotland Clair Brown, Police Scotland John Fleming, Dalavich Community Council Duncan Martin, Oban Community Council (item 10 onwards) Innes McQueen, Comann na Gaidhlig Development Officer Maureen Evans, CLD Youth Worker Sarah Lawlor, Oban Youth Forum Rachel Lawlor, Oban Youth Forum Councillor Elaine Robertson Marri Malloy, Oban Community Council Liam Griffin, Kilmore Community Council Rita Campbell, Press and Journal Sean McKenzie, BBC Alba Kevin Irvine, Oban Youth Cafe 1. WELCOME AND APOLOGIES The Chair welcomed everyone to the meeting and general introductions were made. Apologies for absence were intimated by: Jane Darby, Kilmore Community Council Kirsty McLuckie, Oban Youth Café Jessie McFarlane, Oban Community Council 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST No declarations of interest were intimated. 3. MINUTES (a) Oban, Lorn and the Isles Area Community Planning Group - 14th November 2018 The minute of the Oban, Lorn and the Isles Area Community Planning Group meeting of 14th November 2018 was approved as a correct record subject to three changes at item 11(a). Dalavich Community Update – John Fleming attended the meeting as the Chair of Avich & Kilchrenan Community Council and is not a Director of Dalavich Improvement Group, the Loch shore glamping pods are not run by Dalavich Improvement Group they just rent out the land, and removal of the last line of the update regarding small boat houses. -

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week Ending 12 May2017

Weekly Planning list for 12 May2017 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 12 May2017 12/5/2017 10:19 Weekly Planning list for 12 May2017 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 17/00460/ADV Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 06 - Cowal Community Council: Kilfinan Community Council Proposal: Erection of signage Location: The Pierhouse,Tighnabr uaich, Argyll And Bute,PA21 2EA Applicant: Mr Donald Clark DC Marine,Alma Cottage,Tighnabr uaich, Argyll, PA21 2EB Ag ent: N/A Development Type: 15 - Adver tisements Grid Ref: 198571 - 673307 Reference: 17/01037/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 07 - Dunoon Community Council: Dunoon Community Council Proposal: Use of land for the siting of shipping containers and associated works(par t retrospective) Location: 361 Argyll Street, Dunoon, Argyll And Bute,PA23 7RN Applicant: Walkers Garden Centre 361 Argyll Street , Dunoon , Argyll And Bute,PA23 7RN Ag ent: Architeco Ltd 43 Argyll Street, Dunoon, Argyll, PA23 7HG Development Type: 10B - Other developments - Local Grid Ref: 217216 - 677826 Reference: 17/01057/CONAC Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Complete demolition of tower Location: St Brendans Church, MountstuartRoad, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute,PA20 9EB Applicant: George Hanson (Building Contractors) Ltd 20 Union Street, Rothesay, UK, PA20 0HD Ag ent: Honeyman JackAnd -

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34)

Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council Etive coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impactsSummary At risk of flooding • 20 residential properties • 30 non-residential properties • £100,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling 357 Section 2 Highland and Argyll Local Plan District Loch Awe (Potentially Vulnerable Area 01/34) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Highland and Argyll Argyll and Bute Council River Awe Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is The main rivers are the Awe and the located around Loch Awe and includes Orchy. -

Appendix 1 Draft WS V1.11 PDF 11 MB

Contents LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL i Contents LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL ii 1.0 Introduction 1 – 3 What is the Argyll and Bute Local Development Plan 2? What does the Argyll and Bute Local Development Plan 2 contain? Supplementary Guidance and Technical Notes The Wider Policy Context Overarching Strategies at a Local and Regional Level National Strategies and Policies International Legislation Implementation and Delivery Going Forward 2.0 Vision and Objectives 4 – 7 Vision High Quality Places Diverse and Sustainable Economy Connected Places Sustainable Communities Homes for People High Quality Environment 3.0 Spatial and Settlement Strategy 8 - 25 Settlement and Development Strategy Diagram 1 – Spatial Strategy The Allocations Potential Development Areas (PDAs) Policy 01 – Settlement Areas Policy 02 – Outwith Settlement Areas Oban Strategic Development Framework Proposal: Oban Strategic Development Framework Diagram 2 – Tobermory-Dalmally Growth Corridor Diagram 3 – Oban Development Road Action Area Helensburgh and Lomond Growth Area Proposal: Helensburgh Strategic Development Framework Diagram 4 – Helensburgh and Lomond Growth Area Bowmore Strategic Development Framework Proposal: Bowmore Strategic Development Framework Tobermory Strategic Development Framework Proposal: Tobermory Strategic Development Framework Cruachan Dam Pumped Storage Hydro-Electricity Facility Expansion Proposal: Cruachan Dam Pumped Storage Hydro-Electricity Facility Expansion Simplified Planning Zones and Masterplan Consent -

Community Action Plan 2016 – 2021

DaLavIch Improvement Group community action plan 2016 – 2021 photo: Chrissie Sugden Dalavich, Kilmaha, Inverinan and Lochavich table of contents Local people have their Say ............................................................................................................1 Background ......................................................................................................................................2 our community now and our hopes for the Future ......................................................................3 Location , Population , Housing , Facilities and Employment , Education , Transport and Services , Environment and Heritage community views Survey ................................................................................................................4 Likes Dislikes our vision for the Future ................................................................................................................5 main themes and priorities ..........................................................................................................6 Community Centre ....................................................................................................................6 Infrastructure and Services ........................................................................................................7 Communication/Community Spirit ............................................................................................8 Local Environment ....................................................................................................................9 -

Avich & Kilchrenan Community Council

AVICH & KILCHRENAN COMMUNITY COUNCIL Tigh-an-Drochaid, Kilchrenan, &Yll, PA35 1HD. Mr. A. MacASkill, UlliniSh, Balvicar, BY Oban, Argyll, PA34 4TE. 1 December 200 1~ . Dear Allan, ProDosed Wind Farm - An Suidhe R8.TiTo. 01 703 18/DET Once again we wish to object to the above Wind Farm. Our reasons are the Same as last time. Please find attached. I am sure, of course, that we will receive the new up-dated Maps, Diagrams, Photo Montages, etc., very soon. We should be grateful if you would, therefore, inform the appropriate departments of Argyll and Bute Council, or failing this, let us know to whom we should write. Yours sincerely, Marilyn Henderson, Secretary. P.S. It's all go here. Three causes for concern. (1) The New Water Treatment Plant. (2) The Roads Winter Maintenance between Dalavich and Ford. The an Suidhe (3) ,Proposed Wind Farm at AVICH & KILCHRENAN COMMUNITY COUNCIL Tigh-an-Drochaid, Kilchrenan, AGYll, PA35 IHD. Scottish Executive Reporters Unit, 2 Greenside Lane, EDINBURGH. 24th August 200 1 Dear Sirs, Proposed Wind Farm at an Suidhe. kgy!! Obiection Once again, we wish to place an objection to the above. The following are our reasons: - Visual Obiections 1. From the Maps, Diagrams and Photo Montages, it is evident that the places where the proposed Wind Farm will be most conspicuous are two of the outstanding vistdviewpoints on the public road from Kilchrenan to Ford at (a) What was at one time “OSPREY VIEWPOINT” above Kilmun - shown as Visualisation 4 and (b) Kilrnaha Viewpoint - Visualisation 2. BUT According to Map 6, both of these sites are outwith the ‘Zone of Visual Influence to Hub Height” - which makes Map 6 a complete nonsense! ! 2. -

01501 (ROH) Dalavich , Item 7. PDF 178 KB

Argyll and Bute Council Development Services Delegated or Committee Planning Application Report and Report of Handling as required by Schedule 2 of the Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2008 relative to applications for Planning Permission or Planning Permission in Principle ____________________________________________________________________________ Reference No : 13/01501/PP Planning Hierarchy : Local Development Applicant : Mr David Winter, Aweside Developments Ltd Proposal : Relocation of existing Plots 22 and 24 to new Plots 4a and 8, additional new Plots 5a, 18a and 37 and repositioning of chalets on Plots 17 and 18 Site Address : Dalavich Chalet Park, Dalavich, Argyll and Bute ____________________________________________________________________________ DECISION ROUTE Local Government Scotland Act 1973 ____________________________________________________________________________ (A) THE APPLICATION (i) Development Requiring Express Planning Permission • Relocation of existing Plots 22 and 24 to new Plots 4a and 8; • Additional new Plots 5a, 18a and 37; • Repositioning of proposed chalets on Plots 17 and 18; • Construction of 14 on-site vehicular parking spaces and associated turning arrangements. (ii) Other specified operations • Use of an existing private water supply; • Use of an existing communal private sewage treatment plant; • New tree planting. ____________________________________________________________________________ (B) RECOMMENDATION: Having due regard to the Argyll and Bute Development Plan and all other material planning considerations, including the masterplan submitted for PDA 5/115, it is recommended that planning permission be granted subject to: i) the prior conclusion of a Section 75 legal agreement preventing the implementation of permission for cabins on Plots 22 and 24 as previously approved under 06/01640/DET; ii) a discretionary local hearing being held in view of the third party representations received; iii) the conditions and reasons appended to this Report of Handling. -

Registration Districts of Scotland Guide

Alpha RD Name County or Burgh First yearLast year Rd Number Current Rd A Abbey (Burghal) Renfrew 1855 1878 Old RD 559 1 Today's RD 646 A Abbey (Landward) Renfrew 1855 1878 Old RD 559 2 Today's RD 644 A Abbey (Paisley) Renfrew 1670 1854 OPR 559 A Abbey St.Bathans Berwick 1715 1854 OPR 726 A Abbey St.Bathans Berwick 1855 1966 Old RD 726 Today's RD 785 A Abbotrule (Southdean and Abbotrule) Roxburgh 1696 1854 OPR 806 A Abbotshall Fife 1650 1854 OPR 399 A Abbotshall (Landward) Fife 1855 1874 Old RD 399 Today's RD 421 A Abdie Fife 1620 1854 OPR 400 A Abdie Fife 1855 1931 Old RD 400 Today's RD 416 A Aberchirder Banff 1968 1971 Old RD 146 Today's RD 294 A Aberchirder Banff 1972 2000 Old RD 294 Today's RD 293 A Abercorn Linlithgow (West Lothian) 1585 1854 OPR 661 A Abercorn West Lothian 1855 1969 Old RD 661 Today's RD 701 A Abercrombie or St.Monance Fife 1628 1854 OPR 454 A Aberdalgie Perth 1613 1854 OPR 323 A Aberdalgie Perth 1855 1954 Old RD 323 Today's RD 390 A Aberdeen Aberdeen 1560 1854 OPR 168 a A Aberdeen, Eastern District Aberdeen 1931 1967 Old RD 168 3 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeen, Northern District Aberdeen 1931 1967 Old RD 168 1 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeen, Old Machar Parish Aberdeen 1886 1897 Old RD 168 2 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeen, Southern District Aberdeen 1931 1967 Old RD 168 2 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeen Aberdeen 1968 1971 Old RD 168 A Aberdeen Aberdeen City 1972 2006 Old RD 300 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeen Aberdeen City 2007 Today's RD 300 A Aberdeenshire Aberdeenshire 2005 Today's RD 295 A Aberdour Fife 1650 1854 OPR 401 A Aberdour Aberdeen -

Macphee & Partners DETACHED HOLIDAY CABIN Cabin 32, Dalavich

MacPhee & Partners DETACHED HOLIDAY CABIN OBAN OFFICE Tel: 01631 565 251 Cabin 32, Dalavich Fax: 01631 565 434 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.macphee.co.uk GUIDE PRICE: £69,000 Set in approximately half an acre of scenic woodland close to the shores of Loch Awe, Cabin 32 presents an idyllic getaway overlooking a natural stream. With accommodation comprising open plan kitchen/living/dining area, two fitted bedrooms and shower room, the cabin sleeps six and offers excellent holiday letting potential. Leading off from the open plan living area is a raised decked balcony from which to enjoy the peaceful surroundings, while the cabin further benefits from riparian fishing rights on Loch Awe. All fixtures, fittings and furniture are included in the sale. The village of Dalavich is situated on the banks of Loch Awe, one of Scotland’s largest and most picturesque freshwater lochs with its wooded shores and scattered small islands and is a popular destination for anglers, hill walkers and holiday makers. The village is host to a well stocked General Store which includes a Post Office and a café and there is also a community run Restaurant and Bar. Further facilities and amenities can be located in Oban which forms the ‘Gateway to the Isles’ some 24 miles to the west or in Lochgilphead some 20 miles to the South. Detached Holiday Cabin Woodland Setting Fishing Rights on Loch Awe Excellent Holiday Letting Potential Rural Village Location Open Plan Lounge/Kitchen/ Dining Room 2 Bedrooms Shower Room Store Under Cabin Electric Heating EPC Rating: F 32 Accommodation Stable hardwood door leading into living area.