The Women of the First Aliyah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: a Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Published as part of the publication series: Israel's Relations with Arab Countries: The Unfulfilled Potential Yitzhak Gal May 2018 Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Yitzhak Gal* May 2018 The history of Israel-Jordan relations displays long-term strategic cooperation. The formal peace agreement, signed in 1994, has become one of the pillars of the political-strategic stability of both Israel and Jordan. While the two countries have succeeded in developing extensive security cooperation, the economic, political, and civil aspects, which also have great cooperation potential, have for the most part been neglected. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict presents difficulties in realizing this potential while hindering the Israel-Jordan relations and leading to alienation and hostility between the two peoples. However, the formal agreements and the existing relations make it possible to advance them even under the ongoing conflict. Israel and Jordan can benefit from cooperation on political issues, such as promoting peace and relations with the Palestinians and managing the holy sites in Jerusalem; they can also benefit from cooperation on civil matters, such as joint management of water resources, and resolving environmental, energy, and tourism issues; and lastly, Israel can benefit from economic cooperation while leveraging the geographical position of Jordan which makes it a gateway to Arab markets. This article focuses on the economic aspect and demonstrates how such cooperation can provide Israel with a powerful growth engine that will significantly increase Israeli GDP. It draws attention to the great potential that Israeli-Jordanian ties engender, and to the possibility – which still exists – to realize this potential, which would enhance peaceful and prosperous relationship between Israel and Jordan. -

The Idea of Israel: a History of Power and Knowledge,By Ilan Pappé

Recent Books The Idea of Israel: A History of Power and Knowledge,by Ilan Pappé. London and New York: Verso, 2014. 335 pages. Further Reading and Index to p. 346. $26.95 hardcover. REVIEWED BY GILBERT ACHCAR Ilan Pappé is well known to the readers of this journal as a prolific author of Palestine studies and one of the Israeli intellectuals who engaged most radically in the deconstruction and refutation of the Zionist narrative on Palestine. This book is primarily an incursion, by Pappé, into Israel studies: it is a work not directly about Palestine, but rather about Israel. More precisely, it is about the battle over “the idea of Israel” (i.e., the representation of the Zionist state that prevails in Israel and the challenge Israeli intellectuals pose to that representation). In many ways, Pappé’s new book is a continuation and expansion of his autobiographic Out of the Frame: The Struggle for Academic Freedom in Israel (2010), in which he describes his personal trajectory. In his new book, he provides the wider picture: the historical, intellectual, and political context that led to the emergence, rise to fame, and dwindling of the group of New Historians and “post- Zionist” figures of the Israeli academic and cultural scenes, of which Pappé was and remains a prominent member. The Idea of Israel starts by setting the backdrop to this development. In a short first part, Pappé sketches the main contours of the academic and fictional representation of Israel that complemented official Zionist ideology during the state’s first decades. The second part of the book, entitled “Israel’s Post-Zionist Moment,” constitutes its core. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism

ANTI-ZIONISM AND ANTISEMITISM WHAT IS ANTI-ZIONISM? Zionism is derived from the word Zion, referring to the Biblical Land of Israel. In the late 19th century, Zionism emerged as a political movement to reestablish a Jewish state in Israel, the ancestral homeland of the Jewish People. Today, Zionism refers to support for the continued existence of Israel, in the face of regular calls for its destruction or dissolution. Anti-Zionism is opposition to Jews having a Jewish state in their ancestral homeland, and denies the Jewish people’s right to self-determination. HOW IS ANTI-ZIONISM ANTISEMITIC? The belief that the Jews, alone among the people of the world, do not have a right to self- determination — or that the Jewish people’s religious and historical connection to Israel is invalid — is inherently bigoted. When Jews are verbally or physically harassed or Jewish institutions and houses of worship are vandalized in response to actions of the State of Israel, it is antisemitism. When criticisms of Israel use antisemitic ideas about Jewish power or greed, utilize Holocaust denial or inversion (i.e. claims that Israelis are the “new Nazis”), or dabble in age-old xenophobic suspicion of the Jewish religion, otherwise legitimate critiques cross the line into antisemitism. Calling for a Palestinian nation-state, while simultaneously advocating for an end to the Jewish nation-state is hypocritical at best, and potentially antisemitic. IS ALL CRITICISM OF ISRAEL ANTISEMITIC? No. The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s Working Definition of Antisemitism (“the IHRA Definition”) — employed by governments around the world — explicitly notes that legitimate criticism of Israel is not antisemitism: “Criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.”1 When anti-Zionists call for the end of the Jewish state, however, that is no longer criticism of policy, but rather antisemitism. -

Israeli Historiograhy's Treatment of The

Yechiam Weitz Dialectical versus Unequivocal Israeli Historiography’s Treatment of the Yishuv and Zionist Movement Attitudes toward the Holocaust In November 1994, I helped organize a conference called “Vision and Revision.” Its subject was to be “One Hundred Years of Zionist Histo- riography,”1 but in fact it focused on the stormy debate between Zionists and post-Zionists or Old and New Historians, a theme that pervaded Is- rael’s public and academic discourse at the time. The discussion revolved around a number of topics and issues, such as the birth of the Arab refugee question in the War of Independence and matters concerning the war itself. Another key element of the controversy involved the attitude of the Yishuv (the Jewish community in prestate Israel) and the Zionist move- ment toward the Holocaust. There were several parts to the question: what was the goal of the Yishuv and the Zionist leadership—to save the Jews who were perishing in smoldering Europe or to save Zionism? What was more important to Zionism—to add a new cowshed at Kib- butz ‘Ein Harod and purchase another dunam of land in the Negev or Galilee or the desperate attempt to douse the European inferno with a cup of water? What, in those bleak times, motivated the head of the or- ganized Yishuv, David Ben-Gurion: “Palestinocentrism,” and perhaps even loathing for diaspora Jewry, or the agonizing considerations of a leader in a period of crisis unprecedented in human history? These questions were not confined to World War II and the destruc- tion of European Jewry (1939–45) but extended back to the 1930s and forward to the postwar years. -

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip FRONT COVER United Nations Environment Programme First published in March 2006 by the United Nations Environment Programme. © 2006, United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 92-807-2697-8 Job No.: DEP/0810/GE United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This revised edition includes grammatical, spelling and editorial corrections to a version of the report released in March 2006. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher or the participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimination of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs in this publication were taken by the UNEP Gaza assessment mission team. Cover Design and Layout: Matija Potocnik -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

Down with Britain, Away with Zionism: the 'Canaanites'

DOWN WITH BRITAIN, AWAY WITH ZIONISM: THE ‘CANAANITES’ AND ‘LOHAMEY HERUT ISRAEL’ BETWEEN TWO ADVERSARIES Roman Vater* ABSTRACT: The imposition of the British Mandate over Palestine in 1922 put the Zionist leadership between a rock and a hard place, between its declared allegiance to the idea of Jewish sovereignty and the necessity of cooperation with a foreign ruler. Eventually, both Labour and Revisionist Zionism accommodated themselves to the new situation and chose a strategic partnership with the British Empire. However, dissident opinions within the Revisionist movement were voiced by a group known as the Maximalist Revisionists from the early 1930s. This article analyzes the intellectual and political development of two Maximalist Revisionists – Yonatan Ratosh and Israel Eldad – tracing their gradual shift to anti-Zionist positions. Some questions raised include: when does opposition to Zionist politics transform into opposition to Zionist ideology, and what are the implications of such a transition for the Israeli political scene after 1948? Introduction The standard narrative of Israel’s journey to independence goes generally as follows: when the British military rule in Palestine was replaced in 1922 with a Mandate of which the purpose was to implement the 1917 Balfour Declaration promising support for a Jewish ‘national home’, the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine gained a powerful protector. In consequence, Zionist politics underwent a serious shift when both the leftist Labour camp, led by David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), and the rightist Revisionist camp, led by Zeev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), threw in their lot with Britain. The idea of the ‘covenant between the Empire and the Hebrew state’1 became a paradigm for both camps, which (temporarily) replaced their demand for a Jewish state with the long-term prospect of bringing the Yishuv to qualitative and quantitative supremacy over the Palestinian Arabs under the wings of the British Empire. -

The Case for Amending the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty

The Atkin Paper Series Saving peace: The case for amending the Egypt-Israel peace treaty Dareen Khalifa, ICSR Atkin Fellow February 2013 About the Atkin Paper Series Thanks to the generosity of the Atkin Foundation, the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) offers young leaders from Israel and the Arab world the opportunity to come to London for a period of four months. The purpose of the fellowship is to provide young leaders from Israel and the Arab world with an opportunity to develop their ideas on how to further peace and understanding in the Middle East through research, debate and constructive dialogue in a neutral political environment. The end result is a policy paper that will provide a deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event. Author Dareen holds an MA in Human Rights from University College London, and a BA in Political Science from Cairo University. She has been working as a consultant for Amnesty International in London. In Egypt she worked on human rights education and advocacy with the National Council for Human Rights, in addition to a number of nongovernmental human rights organisations. Dareen has also worked as a freelance researcher and as a consultant for a number of civil society organisations and think tanks in Egypt.Additionally, Dareen worked as a Fellow at Human Rights First, Washington DC. She has contributed to several human rights reports, The Global Integrity Anti-Corruption report on Egypt, For a Nation without Torture, and the Verité International Annual Report on Labour Rights in Egypt. -

NBN-Aliyah-Guidebook.Pdf

Welcome In 2002 we asked ourselves (and others), why are so few North Americans making Aliyah? What is holding people back? How can Aliyah be done differently? Can the process be improved? And if it can, will Aliyah increase? Will answering these questions encourage more people to make the move? What would a wave of increased Aliyah look like? 15 YEARS AND 50,000 OLIM LATER, THE ANSWER IS CLEAR. Imagining greater possibities was not a one-time exercise. It is the underlying principle that guides Nefesh B’Nefesh services, helps us The mission of Nefesh B’Nefesh identify where to improve, what resources to make available and the is to make the Aliyah process obstacles to help alleviate. easier, facilitate the integration BUT THIS IS ONLY HALF THE STORY. of new Olim into Israeli society and to educate the Jews of the It is our community of Olim who, on a very personal level, are asking Diaspora as to the centrality of themselves the same questions. the Israel to the Jewish People. The individuals and families who are choosing to imagine greater possibilities, seeing greater potential, a greater future… and are By removing professional, choosing a different path from the overwhelming majority of their logistical and financial peers, families and communities. obstacles, and sharing the AND WHAT ARE THEY FINDING? Aliyah story of Olim actively building the State of Israel,we Aside from the basics, they are finding warm communities, great jobs, and holistic Jewish living. They are tapping into something bigger – encourage others to actualize there is a tangible feeling of being part of Israel’s next chapter and their Aliyah dreams. -

Financial Aid, Services & Aliyah Processing Application

Name of Applicant: Estimated Aliyah Date _______/_______ Last Name, First Name month year City of Residence: City, State Email Address: Financial Aid, Services & Aliyah Processing Application Place photo here Units: Date Received: For Internal In cooperation with Use Only For questions related to your Aliyah, please FA_022411 call Nefesh B’Nefesh at 1-866-4-ALIYAH. Nefesh B'Nefesh Services Nefesh B'Nefesh aims to ease the financial burden associated with Aliyah by providing a financial buffer for Olim and helping supplement the requisite relocation expenses, thereby alleviating the somewhat prohibitive costs of Aliyah. We provide support to our Olim both before and after their Aliyah for employment, social services and government assistance, in order to help make their Aliyah as seamless and successful as possible. Below is a brief description of the services and resources available to Olim. Financial Government Advocacy & Guidance The costs associated with pilot trips, finding a home, Our Government Advocacy & Guidance Department and purchasing and shipping household appliances and is ready to assist Olim with questions regarding Oleh furnishings can be challenging. Often it takes several years benefits, government processing, and any other aspect of to earn and save enough funds necessary for the move. For a their absorption. The answers to many frequently asked family, by the time the requisite amount is saved, the children questions about Aliyah and benefits can be found on our are invariably at an age that makes a move difficult socially, website (see below). linguistically and educationally. To obviate these fiscal obstacles, Nefesh B'Nefesh provides Absorption and Integration financial assistance to each eligible individual or family to Our Absorption and Integration Department provides enable them to make their dream of Aliyah a reality. -

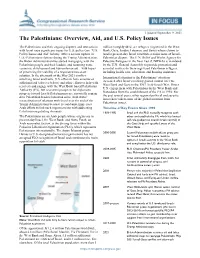

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim.