The Case for Amending the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: a Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled

Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Published as part of the publication series: Israel's Relations with Arab Countries: The Unfulfilled Potential Yitzhak Gal May 2018 Israel-Jordan Cooperation: A Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled Yitzhak Gal* May 2018 The history of Israel-Jordan relations displays long-term strategic cooperation. The formal peace agreement, signed in 1994, has become one of the pillars of the political-strategic stability of both Israel and Jordan. While the two countries have succeeded in developing extensive security cooperation, the economic, political, and civil aspects, which also have great cooperation potential, have for the most part been neglected. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict presents difficulties in realizing this potential while hindering the Israel-Jordan relations and leading to alienation and hostility between the two peoples. However, the formal agreements and the existing relations make it possible to advance them even under the ongoing conflict. Israel and Jordan can benefit from cooperation on political issues, such as promoting peace and relations with the Palestinians and managing the holy sites in Jerusalem; they can also benefit from cooperation on civil matters, such as joint management of water resources, and resolving environmental, energy, and tourism issues; and lastly, Israel can benefit from economic cooperation while leveraging the geographical position of Jordan which makes it a gateway to Arab markets. This article focuses on the economic aspect and demonstrates how such cooperation can provide Israel with a powerful growth engine that will significantly increase Israeli GDP. It draws attention to the great potential that Israeli-Jordanian ties engender, and to the possibility – which still exists – to realize this potential, which would enhance peaceful and prosperous relationship between Israel and Jordan. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism

ANTI-ZIONISM AND ANTISEMITISM WHAT IS ANTI-ZIONISM? Zionism is derived from the word Zion, referring to the Biblical Land of Israel. In the late 19th century, Zionism emerged as a political movement to reestablish a Jewish state in Israel, the ancestral homeland of the Jewish People. Today, Zionism refers to support for the continued existence of Israel, in the face of regular calls for its destruction or dissolution. Anti-Zionism is opposition to Jews having a Jewish state in their ancestral homeland, and denies the Jewish people’s right to self-determination. HOW IS ANTI-ZIONISM ANTISEMITIC? The belief that the Jews, alone among the people of the world, do not have a right to self- determination — or that the Jewish people’s religious and historical connection to Israel is invalid — is inherently bigoted. When Jews are verbally or physically harassed or Jewish institutions and houses of worship are vandalized in response to actions of the State of Israel, it is antisemitism. When criticisms of Israel use antisemitic ideas about Jewish power or greed, utilize Holocaust denial or inversion (i.e. claims that Israelis are the “new Nazis”), or dabble in age-old xenophobic suspicion of the Jewish religion, otherwise legitimate critiques cross the line into antisemitism. Calling for a Palestinian nation-state, while simultaneously advocating for an end to the Jewish nation-state is hypocritical at best, and potentially antisemitic. IS ALL CRITICISM OF ISRAEL ANTISEMITIC? No. The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s Working Definition of Antisemitism (“the IHRA Definition”) — employed by governments around the world — explicitly notes that legitimate criticism of Israel is not antisemitism: “Criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.”1 When anti-Zionists call for the end of the Jewish state, however, that is no longer criticism of policy, but rather antisemitism. -

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip FRONT COVER United Nations Environment Programme First published in March 2006 by the United Nations Environment Programme. © 2006, United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 92-807-2697-8 Job No.: DEP/0810/GE United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This revised edition includes grammatical, spelling and editorial corrections to a version of the report released in March 2006. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher or the participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimination of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs in this publication were taken by the UNEP Gaza assessment mission team. Cover Design and Layout: Matija Potocnik -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

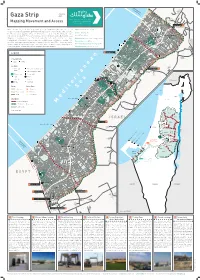

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Overview of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

Overview of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict Origins (to 1949): The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is essentially a modern conflict originating in the 20th century. However, the roots of the conflict – involving competing historical claims to the same stretch of land - go back thousands of years. Jewish roots in the area began sometime between 1800 and 1500 B.C. when the Hebrew people, a Semitic group, migrated into Canaan (today’s Israel). Around 1000 B.C., their descendants formally established the kingdom of Israel with Jerusalem as its capital. Israel soon split into two kingdoms and was frequently under the control of foreign conquerors: the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and ultimately the Romans. However, despite repeated conquests, the Jews always retained their separate identity, mostly because of their distinctive religious beliefs. The fact that the Jews were monotheists (believers in one God), while their neighbors were polytheists set the Jews apart and instilled in them the idea that the territory of Israel was their “promised land.” The Jewish majority in that land was ended, however, when the Roman Empire expelled the Jewish population from Israel following a failed revolt against Roman rule in 135 AD. For the next 1,800 years, the majority of Jews lived in scattered Diasporas (ethnic communities outside of their traditional homeland) throughout Europe and the Middle East. Meanwhile, the land, which the Romans now named ‘Palaestina,’ or ‘Palestine’ in its English form, was inhabited by small groups of Jews, who had gradually returned to the area, along with other local peoples and some colonists brought in by the Romans. -

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Global Classroom Workshops made possible by: THE Photo Courtesy of Bill Taylor NORCLIFFE FOUNDATION A Resource Packet for Educators Compiled by Kristin Jensen, Jillian Foote, and Tese Wintz Neighbor And World May 12, 2009 Affairs Council Members HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE GUIDE Please note: many descriptions were excerpted directly from the websites. Packet published: 5/11/2009; Websites checked: 5/11/2009 Recommended Resources Links that include… Lesson Plans & Charts & Graphs Teacher Resources Audio Video Photos & Slideshows Maps TABLE OF CONTENTS MAPS 1 FACT SHEET 3 TIMELINES OF THE CONFLICT 4 GENERAL RESOURCES ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 5 TOPICS OF INTEREST 7 CURRENT ARTICLES/EDITORIALS ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 8 (Focus on International Policy and Peace-Making) THE CRISIS IN GAZA 9 RIPPED FROM THE HEADLINES: WEEK OF MAY 4TH 10 RELATED REGIONAL ISSUES 11 PROPOSED SOLUTIONS 13 ONE-STATE SOLUTION 14 TWO-STATE SOLUTION 14 THE OVERLAPPING CONUNDRUM – THE SETTLEMENTS 15 CONFLICT RESOLUTION TEACHER RESOURCES 15 MEDIA LITERACY 17 NEWS SOURCES FROM THE MIDEAST 18 NGOS INVOLVED IN ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS 20 LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS & RESOURCES 22 DOCUMENTARIES & FILMS 24 BOOKS 29 MAPS http://johomaps.com/as/mideast.html & www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/is.html Other excellent sources for maps: From the Jewish Virtual Library - http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/maptoc.html Foundation for Middle East Peace - http://www.fmep.org/maps/ -

THE GREAT POWERS and the EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Boston University THE GREAT POWERS and the EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN CAS IR 325 / HI 229 Fall Semester 2016 Tuesday and Thursday 11:00-12:30 Prof. Erik Goldstein Office Hours: Tues./ Thurs. 2-3 Office: 152 Bay State Road, 3rd Floor Thurs: 9.30-10.30 Telephone: 353-9280 tel. preferred to email COURSE SYLLABUS Course Description This course will look at the Eastern Mediterranean as a centre of Great Power confrontation, and consider such issues as the impact of the competition on wider international relations, the domestic impact on the region of this involvement, the role of seapower, the origins and conduct on wars in the region, and attempts at conflict resolution. Objectives To provide an understanding of the nature of Great Power rivalry, to gain insight into the underlying factors affecting international relations in the Eastern Mediterranean, and to consider how governments evolve and implement policy. Requirements Mid-term examination 30% (18 Oct. 2016) Comprehensive final examination. 70% (to be detemined by University Registrar) All class members are expected to maintain high standards of academic honesty and integrity. The College of Arts and Sciences’ pamphlet “Academic Conduct Code” provides the standards and procedures. Cases of suspected academic misconduct will be referred to the Dean’s Office. Students are reminded that attendance is required, and reasons for non-attendance should be notified to the instructor. Cell phones are to be turned off. Repeated disruption caused by phones ringing will result in a grade penalty to be determined by the instructor. Laptops should be used for class purposes only during class. -

Israel's Wars, 1947-93

Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Warfare and History General Editor Jeremy Black Professor of History, University of Exeter European warfare, 1660–1815 Jeremy Black The Great War, 1914–18 Spencer C. Tucker Wars of imperial conquest in Africa, 1830–1914 Bruce Vandervort German armies: war and German politics, 1648–1806 Peter H. Wilson Ottoman warfare, 1500–1700 Rhoads Murphey Seapower and naval warfare, 1650–1830 Richard Harding Air power in the age of total war, 1900–60 John Buckley Frontiersmen: warfare in Africa since 1950 Anthony Clayton Western warfare in the age of the Crusades, 1000–1300 John France The Korean War Stanley Sandler European and Native-American warfare, 1675–1815 Armstrong Starkey Vietnam Spencer C. Tucker The War for Independence and the transformation of American society Harry M. Ward Warfare, state and society in the Byzantine world, 565–1204 John Haldon Soviet military system Roger Reese Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500–1800 John K. Thornton The Soviet military experience Roger Reese Warfare at sea, 1500–1650 Jan Glete Warfare and society in Europe, 1792–1914 Geoffrey Wawro Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Ahron Bregman Israel’s Wars, 1947–93 Ahron Bregman London and NewYork First published 2000 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, NewYork, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. © 2000 Ahron Bregman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.