Israel-Jordan Cooperation: a Potential That Can Still Be Fulfilled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism

ANTI-ZIONISM AND ANTISEMITISM WHAT IS ANTI-ZIONISM? Zionism is derived from the word Zion, referring to the Biblical Land of Israel. In the late 19th century, Zionism emerged as a political movement to reestablish a Jewish state in Israel, the ancestral homeland of the Jewish People. Today, Zionism refers to support for the continued existence of Israel, in the face of regular calls for its destruction or dissolution. Anti-Zionism is opposition to Jews having a Jewish state in their ancestral homeland, and denies the Jewish people’s right to self-determination. HOW IS ANTI-ZIONISM ANTISEMITIC? The belief that the Jews, alone among the people of the world, do not have a right to self- determination — or that the Jewish people’s religious and historical connection to Israel is invalid — is inherently bigoted. When Jews are verbally or physically harassed or Jewish institutions and houses of worship are vandalized in response to actions of the State of Israel, it is antisemitism. When criticisms of Israel use antisemitic ideas about Jewish power or greed, utilize Holocaust denial or inversion (i.e. claims that Israelis are the “new Nazis”), or dabble in age-old xenophobic suspicion of the Jewish religion, otherwise legitimate critiques cross the line into antisemitism. Calling for a Palestinian nation-state, while simultaneously advocating for an end to the Jewish nation-state is hypocritical at best, and potentially antisemitic. IS ALL CRITICISM OF ISRAEL ANTISEMITIC? No. The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s Working Definition of Antisemitism (“the IHRA Definition”) — employed by governments around the world — explicitly notes that legitimate criticism of Israel is not antisemitism: “Criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.”1 When anti-Zionists call for the end of the Jewish state, however, that is no longer criticism of policy, but rather antisemitism. -

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip

Environmental Assessment of the Areas Disengaged by Israel in the Gaza Strip FRONT COVER United Nations Environment Programme First published in March 2006 by the United Nations Environment Programme. © 2006, United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN: 92-807-2697-8 Job No.: DEP/0810/GE United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This revised edition includes grammatical, spelling and editorial corrections to a version of the report released in March 2006. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The designation of geographical entities in this report, and the presentation of the material herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher or the participating organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimination of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photographs in this publication were taken by the UNEP Gaza assessment mission team. Cover Design and Layout: Matija Potocnik -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

The Case for Amending the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty

The Atkin Paper Series Saving peace: The case for amending the Egypt-Israel peace treaty Dareen Khalifa, ICSR Atkin Fellow February 2013 About the Atkin Paper Series Thanks to the generosity of the Atkin Foundation, the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) offers young leaders from Israel and the Arab world the opportunity to come to London for a period of four months. The purpose of the fellowship is to provide young leaders from Israel and the Arab world with an opportunity to develop their ideas on how to further peace and understanding in the Middle East through research, debate and constructive dialogue in a neutral political environment. The end result is a policy paper that will provide a deeper understanding and a new perspective on a specific topic or event. Author Dareen holds an MA in Human Rights from University College London, and a BA in Political Science from Cairo University. She has been working as a consultant for Amnesty International in London. In Egypt she worked on human rights education and advocacy with the National Council for Human Rights, in addition to a number of nongovernmental human rights organisations. Dareen has also worked as a freelance researcher and as a consultant for a number of civil society organisations and think tanks in Egypt.Additionally, Dareen worked as a Fellow at Human Rights First, Washington DC. She has contributed to several human rights reports, The Global Integrity Anti-Corruption report on Egypt, For a Nation without Torture, and the Verité International Annual Report on Labour Rights in Egypt. -

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

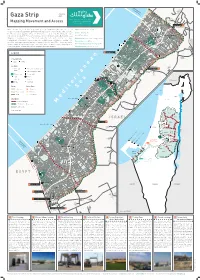

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Overview of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

Overview of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict Origins (to 1949): The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is essentially a modern conflict originating in the 20th century. However, the roots of the conflict – involving competing historical claims to the same stretch of land - go back thousands of years. Jewish roots in the area began sometime between 1800 and 1500 B.C. when the Hebrew people, a Semitic group, migrated into Canaan (today’s Israel). Around 1000 B.C., their descendants formally established the kingdom of Israel with Jerusalem as its capital. Israel soon split into two kingdoms and was frequently under the control of foreign conquerors: the Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and ultimately the Romans. However, despite repeated conquests, the Jews always retained their separate identity, mostly because of their distinctive religious beliefs. The fact that the Jews were monotheists (believers in one God), while their neighbors were polytheists set the Jews apart and instilled in them the idea that the territory of Israel was their “promised land.” The Jewish majority in that land was ended, however, when the Roman Empire expelled the Jewish population from Israel following a failed revolt against Roman rule in 135 AD. For the next 1,800 years, the majority of Jews lived in scattered Diasporas (ethnic communities outside of their traditional homeland) throughout Europe and the Middle East. Meanwhile, the land, which the Romans now named ‘Palaestina,’ or ‘Palestine’ in its English form, was inhabited by small groups of Jews, who had gradually returned to the area, along with other local peoples and some colonists brought in by the Romans. -

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Understanding the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Global Classroom Workshops made possible by: THE Photo Courtesy of Bill Taylor NORCLIFFE FOUNDATION A Resource Packet for Educators Compiled by Kristin Jensen, Jillian Foote, and Tese Wintz Neighbor And World May 12, 2009 Affairs Council Members HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE GUIDE Please note: many descriptions were excerpted directly from the websites. Packet published: 5/11/2009; Websites checked: 5/11/2009 Recommended Resources Links that include… Lesson Plans & Charts & Graphs Teacher Resources Audio Video Photos & Slideshows Maps TABLE OF CONTENTS MAPS 1 FACT SHEET 3 TIMELINES OF THE CONFLICT 4 GENERAL RESOURCES ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 5 TOPICS OF INTEREST 7 CURRENT ARTICLES/EDITORIALS ON THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT 8 (Focus on International Policy and Peace-Making) THE CRISIS IN GAZA 9 RIPPED FROM THE HEADLINES: WEEK OF MAY 4TH 10 RELATED REGIONAL ISSUES 11 PROPOSED SOLUTIONS 13 ONE-STATE SOLUTION 14 TWO-STATE SOLUTION 14 THE OVERLAPPING CONUNDRUM – THE SETTLEMENTS 15 CONFLICT RESOLUTION TEACHER RESOURCES 15 MEDIA LITERACY 17 NEWS SOURCES FROM THE MIDEAST 18 NGOS INVOLVED IN ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS 20 LOCAL ORGANIZATIONS & RESOURCES 22 DOCUMENTARIES & FILMS 24 BOOKS 29 MAPS http://johomaps.com/as/mideast.html & www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/is.html Other excellent sources for maps: From the Jewish Virtual Library - http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/maptoc.html Foundation for Middle East Peace - http://www.fmep.org/maps/ -

Israel-Syria Armistice Agreement

No. 657 ISRAEL and SYRIA General Armistice Agreement (witli annexes and accompany ing letters). Signed at Hill 232, near Mahanayim, on 20 July 1949 -diglish and French official texts communicated by the Permanent Representa tive of Israel to the United Nations. The registration took place on 6 October 1949. ISRAEL et SYRIE Convention d'armistice general (avec annexes et letfcres d'accompagnement). Signee a Cote 232, pres de Mahana yim, le 20 juillet 1949 ' Textes officiels anglais et jrangais communiques par le representant permanent d'Israel aupres de I'Organisation des Nations Unies L'enregistrement a eu . lieu le 6 octobre 1949. 328 United Nations — Treaty-Series 1949! No. 657. ISRAELI-SYRIAN GENERAL ARMISTICE AGREE MENT.1 SIGNED AT HILL 232, NEAR MAHANAYIM, ON 20 JULY 1949 Preamble The Parties to the present Agreement, Responding to the Security Council resolution of 16 November 1948,2 calling upon them, as a further provisional measure under Article 40 of the Charter of the United Nations and in order to facilitate the transition from the present truce to permanent peace in Palestine, to negociate an armistice; Having decided to enter into negotiations under United Nations Chairman ship concerning the implementation of the Security Council resolution of 16 November 1948; and having appointed representatives empowered to negotiate and conclude an Armistice Agreement; The undersigned representatives, having exchanged their full powers found' to be in good and proper form, have agreed upon the following provisions: Article I With a view to promoting the return of permanent peace in Palestine and; in recognition of the importance in this regard of mutual assurances concerning; the future military operations of the Parties, the following principles, which shalli be fully observed by both Parties during the armistice, are hereby affirmed: 1. -

History of Israel: with an Introduction and Appendix by William P

John Bright, A History of Israel: With an Introduction and Appendix by William P. Brown, 4th edition, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. (ISBN 0-664-22068-1) ABBREVIATIONS AASOR Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research AB The Anchor Bible, W.F. Albright (†) and D.N. Freedman, eds., (New York: Doubleday) AJA American Journal of Archaeology AJSL American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures ANEH W.W. Hallo and W.K Simpson, The Ancient Near East: A History (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971) ANEP J.B. Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near East in Pictures (Princeton University Press, 1954) ANET J.B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton University Press, 1950) ANE Suppl. J.B. Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near East: Supplementary Texts and Pictures Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton Univ. Press, 1969) AOTS D. Winton Thomas, ed., Archaeology and Old Testament Study (Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1967) AP W.F. Albright, The Archaeology of Palestine (Penguin Books, 1949; rev. ed., 1960) ARI W.F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (5th ed., Doubleday Anchor Book, 1969) ASTI Annual of the Swedish Theological Institute ASV American Standard Version of the Bible, (1901) ATD Das Alte Testament Deutsch, V. Herntrich (t) and A. Weiser, eds., (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & .Ruprecht) AVAA A. Scharff and A. Moorgat, Ägypten und Vorderasien in Altertum (Munich: F. Bruckmann, 1950) BA The Biblical Archaeologist BANE G.E. Wright, ed., The Bible and the Ancient Near East (New York: Doubleday, 1961) BAR G.E. Wright, Biblical Archaeology (Philadelphia: Westminster Press; London: Gerald Duckworth, 1962) BARev.